July 7, 2022 : Issue #20

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

A jumbo stack to celebrate our twentieth issue, starting with a Walter Murch convergence locating the very center of the universe in a most surprising place. Then, by way of some Weschler family history (my sister’s book, my brother’s game), on into two truly unsettling lists of things really worth fretting over, milded, on the far side, by a swerve into the pastoral sublime. From cosmically centered eggs, in other words, to Koufax on the mound…

* * *

CONVERGENCE CONTEST

A few issues back we opened our convergence contest, inviting fellow Cabineteers to submit their own happenstance convergences (along the lines of the instances inventoried in our “All that is Solid” taxonomic series serialized across issues 11 through 15), and as you may recall, our first winner (even before the contest was announced) was Tristan de Rond, who submitted this uncanny cat’s eye rhyme of a microscopic vantage of a protein and a telescopic image of a black hole.

That in turn inspired longtime Friend of the Cabinet, polymathic film editor Walter Murch (veterans of this stack will recall his speculations on golden ratios across faces and screens in Issue #1 and then on the uncanny mathematics undergirding the Egyptian pyramids in Issue #5) to resubmit a pair of equally rhyming macro and micro vantages (of the skein of farflung galaxies on the one hand, and a splay of neural dendrites on the other) that he’d first submitted to the original McSweeneys convergence contest back in 2006 but then amplified upon in a short film that I coproduced with Brent Hoff for Wholphin, the short-lived McSweeneys DVD quarterly, which is still worth another look.

At that time, Murch had zeroed in on the sort of question he alone seems regularly to surface, in this instance that of which emits more energy, on a per volume basis, the human brain or the sun—the answer proved completely mind-boggling (or, alternatively, sun-crunching), see the video here.

This time, though, he takes that same disconcerting convergence of images (brain/cosmos) in an entirely different, no less astonishing, direction, as you will see below. (At the end of his submission, Walter will respond to a few questions from me.)

CONVERGENCE CONTEST WINNER #2

Submitted by Walter Murch

EGG-CENTRICITY

Proving that human females hold the center of the Universe in the palm of their bellies.

To the left:

Structure of the brain: neurons and synapses 2mm across.

(Université Laval)

To the right:

Structure of the Universe, 1 billion light years across. Each bright pixel is a galaxy. (Max Planck Institute)

The size difference between these two disconcertingly similar images is around 27 orders of magnitude. Written out, that would be 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, or 1e27 using exponential scientific notation: 1 followed by 27 zeros.

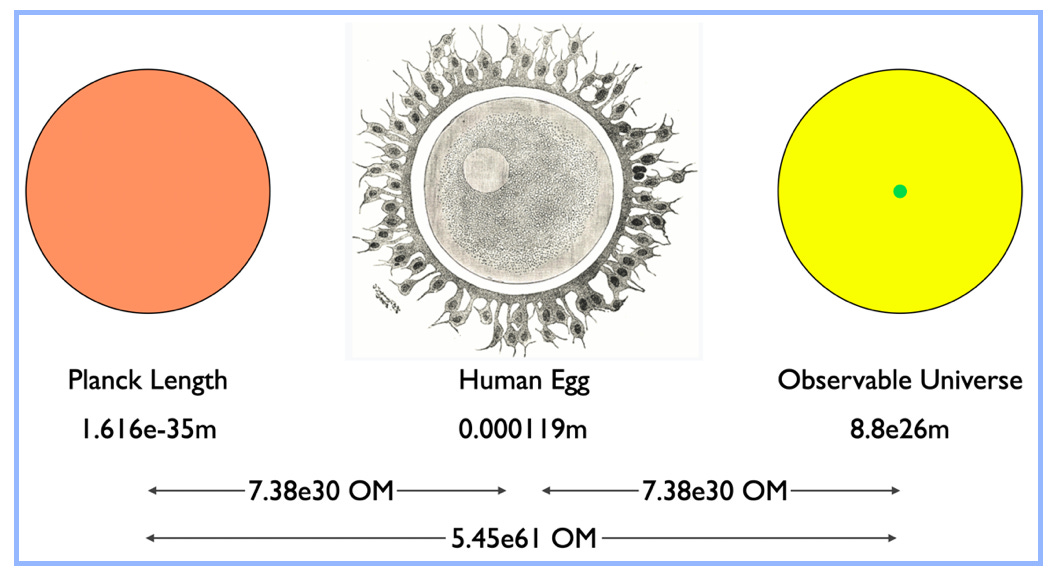

The image of neurons on the left is one billion billion billion times smaller than the image of galaxies on the right. And it takes only two more orders of magnitude, widening out our view of the galaxies on the right by 100 times, to reach the edge of the Observable Universe, which is 93 billion light years in diameter. In meters, that works out to be 8.8e26.

The Observable Universe is the largest thing we can perceive scientifically. At the other end of the scale, the smallest unit of length we can conceive of is called the Planck Length, which is 0.000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 01616 meters, or 1.616e-35 in scientific notation. (More detail on some of the wider aspects of all this in a bit).

We humans exist somewhere along that spectrum from largest to smallest, but where?

If Planck length is 1.616e-35 meters, and the Observable Universe is 8.8e26 meters, how many orders of magnitude separate these two limits?

Dividing the Universe by Planck we get:

8.8e26 / 1.616e-35 = 5.45e61.

So there are almost 62 orders of magnitude between the largest thing we can conceive of, and the smallest.

But curious minds want to know: What is at the midpoint? Not the arithmetical midpoint 4.4e26m—the radius of the observable universe. That is not a very interesting distance.

What we have in mind, rather, is the logarithmic midpoint—something similar to the Golden Mean. Let’s propose a value, X, which is larger than the Planck Length by the same factor that the Observable Universe, in turn, is larger than that X. Putting it another way: if you divide X by the Planck Length you get the same result as dividing the Observable Universe by X. So how do we find X?

In algebraic terms: X divided by Planck equals the Observable Universe divided by X.

Once we have it in this form, we can solve for X. Multiplying both sides by X, we get:

And then multiplying both sides by P we get:

Now find the square root of both sides… X equals the square root of U times P

And now we can plug in the values for U and P and multiply them:

8.8e26 x 1.616e-35 = 0.000 000 014 220 meters

…and then find the square root of that product: 0.000 119 260 meters…

which can also be expressed as 119.26 micrometers, abbreviated 119.26 µm.

Such that X turns out to be 119.26 micrometers.

Αnd 120 µm is the diameter of the human egg!

Wikipedia: The ovum is one of the largest cells in the human body, typically visible to the naked eye without the aid of a microscope or other magnification device. The human ovum measures approximately 120 μm (0.0047 in) in diameter.

Multiply Planck by 7.38e30 to get the Human Egg

Multiply the Egg by 7.38e30 to get the Observable Universe

So there are just as many orders of magnitude “down” (7.38e30) from human Egg to Planck Length as there are “up” from Egg to the Observable Universe.

It seems that humans are at the center of the universe after all! Or rather, women are…

But in fact, the mammalian egg—from rabbit to woman, bat to horse, mouse to whale—is around the same 100-120µm diameter no matter what the species, completely independent of the size of the mammal.

And not only is the mammalian egg at the logarithmic midpoint of the Universe, it is also at the logarithmic midpoint of the relatively narrow band of complexly organized matter on Earth, which extends across only twelve orders of magnitude, from Atom to Sequoia Sempervirens (Coastal Redwood). Hyperion, the tallest tree on Earth (only discovered in 2006) measures 115.92 meters above ground, with a root system extending probably four or five meters down to give a total length of 120.92 meters. (Redwoods have famously shallow roots, averaging 2 to 5 meters deep. Those roots, however, spread out horizontally quite far, interlocking with those of nearby trees for stability and water exchange.)

The diameter of the Hydrogen atom, at 120 picometers, is exactly six orders of magnitude smaller than the diameter of the mammalian Egg, (a picometer is a trillionth of a meter). And six orders larger than that Egg is Hyperion, at just over 120 meters, including root depth.. Those twelve orders of magnitude occupy just one-fifth of the logarithmic spread—sixty-two orders of magnitude—from Planck Length to the diameter of the Observable Universe.

OKAY, SOME QUESTIONS AND A QUOTATION

Q. Are these observations, especially regarding the diameter of the observable universe and the length of the Planck length, based on human observational capacities, or would they be so whether or not we were here to do the observing?

A. The size and location of our observable universe is determined by three factors: the speed of light (which is absolute), the rate of expansion of the universe (which may be variable, but is certainly independent of human desire); and the location of the Observer, which (like the pre-Copernican Geocentric Universe) is centered upon Planet Earth. Tinker with the speed of light or the rate of expansion of the universe, and the diameter of the Observable Universe would expand or contract accordingly.

On the other hand, the observer’s location is definitely not an absolute, as there may be other observers somewhere else in the universe; and depending on how far away they are, they would perceive a slightly different universe than we do: the more distant they are, the more different their universe would appear compared to ours. Observers on a planet in a galaxy 5 billion light years from Earth, for instance, could see the Milky Way (as it was 5 billion years ago) and we could see their galaxy (with the same 5 billion year delay). But they would also see parts of the Universe we cannot see, and vice versa. Think of partially intersecting spherical Venn diagrams (see drawings below). But the diameter of the observable universe would be the same in either case.

Thus, right at the edge of OUR observable universe, an observer, looking in our direction, would see us as we were 13.77 billion years ago. Those two spherical Venn Diagrams would overlap. Those distant observers (on the red dot planet) would see a largely different universe from us (on the blue dot planet). We see the yellow universe from our perspective on Earth. The gray overlap lens-shaped space is what each of us can observe in common (image on the left). If those observers were twice as far away, the two observable universes would have nothing in common (image on the right).

As for Herr Planck and his length, it's a little trickier, as are all things Quantum. Planck Length is dependent on the absolute speed of light: it is 1.616e-35m, the distance light can travel in one unit of Planck Time. What is a unit of Planck Time? 5.4e-44 seconds. But that unit is defined, circularly, by the time it takes light to travel one Planck Length. It is sort of a “turtles all the way down” explanation. Basically, given the nature of things, Planck units, though, turn out to be the threshold beyond which measurement becomes theoretically meaningless. At this point, I yield the floor to Dr. Wiki Pedia.

At any rate, in both cases—Observable Universe and Planck—the limit we reach is the ability to observe anything beyond (larger or smaller). Not just human ability, but THE ability. The absolute ability. We are stuck in a barrel of our own perceptions.

Q. Which brings us back to our friend Nicolas of Cusa: “God is an infinite circle whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” (Incidentally, it turns out that Cusa is only one of dozens of sages to have tolled along similar lines over the centuries, including Voltaire, Pascal, Black Elk, etc., as well. See here.)

A. Amen to that. It’s just the word Infinite which is the problem. The Observable Universe is big, very big, but definitely not infinite. THE Universe may be infinite—it may even be a MultiVerse—but it is un-observable by us because of what was mentioned earlier: the speed of light, the speed of expansion of the universe, and our particular location in the Universe. Those three things impose a “horizon” beyond which we cannot see, and from beyond which no information can reach us. As I say, we are at the bottom of a “barrel” of space-time.

An imperfect two-dimensional analogy: Imagine yourself standing on a very flat, very large desert on the planet Earth. You are six feet tall. Your horizon is around five kilometers distant because of how tall you are and the curvature of the Earth. You are standing in the center of your own “Observable Desert” whose diameter is ten kilometers, and whose area is 78 square kilometers. Someone standing four kilometers from you can be seen (just) and can see you. But they experience a largely different 78 square kilometers of desert than you, and vice versa.

To make that analogy more exact, you would have to imagine the speed of light being very much slower than it is, and that the radius of the Earth was increasing—ultimately increasing faster than the speed of that slow light.

See an animated version of the above here.

Q. Speaking of towering vantage points, is it possible that on other planets in the Milky Way, or in other galaxies, there are forms of naturally-organized matter larger than sequoias?

A. Yes. Gravity and hydrostatic pressure are limiting factors in the height of trees here on Earth, so on a planet with weaker gravity and a different atmospheric pressure, life forms might be able to get larger than here on Earth. (For that matter, in the 19th century there were reports of eucalyptus trees in Australia, and Douglas firs in British Columbia, in excess of 120 meters.)

On the other hand, gravity is much less of a factor for life in the Earth’s oceans, yet we do not see sequoia-sized organisms growing there. The largest ocean animal is the Blue Whale, whose length is only 30 meters, one-quarter the height of a redwood tree. (In fact, it seems the Blue Whale is the largest animal to have ever existed on Earth—dinosaurs included.)

However, it is highly unlikely that anywhere in this Universe there will be Hydrogen atoms smaller than 120 picometers in diameter.

Q: Do all of those calculations earlier on only apply in mathematical systems based on ten, rather than say five or eleven, in which case would it only apply to a system generated by a creature that just happened to have ten fingers? Chickens have four fingers on each foot: would Chicken-Murch be making the same observations as Human-Murch does? (I ask in part because we all know that Human-Murch’s wife Aggie used to raise chickens.)

A: It’s all about ratios, so it would apply no matter the mathematical system, binary 1’s and 0’s, human-base 10, or a chicken-based quaternary system—which by the way is the mathematics of DNA with its four letters (A, G, C, T).

Q: Do you remember the old Woody Allen joke? Guy walks into a psychiatrist's office and says, Hey doc, my brother's crazy! He thinks he's a chicken. The doc asks, Why don't you disabuse him of this notion? The guy says, We would but we need the eggs.

A: No.

* * *

Some Weschler family history, by way of a bridge between the preceding and the forthcoming

Who’s really going to love Walter’s assertion of the cosmic centrality of the human ovum is my sister Toni. I know: she’s already told me that she may well lead the next, 30th anniversary, edition of her book with it.

A word about Toni and her book. My kid sister has basically produced one book in her entire career and it has sold more copies than all twenty of my books put together, by several orders of magnitude, as Walter would say. Her book is almost always in the top 1,000 on Amazon, whereas my various tomes tend to bob in the 30,000 region if I’m lucky or even further back, way further back. One time, one of my books was featured in a big half-hour piece on “All Things Considered” after which I opened my laptop to check out how things were trending over at Amazon, and indeed, my book was suddenly edging out my sister’s! I quickly zapped her an email: “Eat my dust.” By return email, she replied, “Look again.”

It is regularly the case that following readings of my own books, some nice lady in the book-signing line will lean over confidentially and inquire, whisperingly, “Are you by any chance related to Toni Weschler?” and when I affirm that indeed I am, said lady will invariably turn to the back of the hall and squeal, “Oh my God, he is, he is! Oh my God, bring the baby here. Here, here, this is our baby, Antoinette, named after your sister because she wouldn’t even be here if it weren’t for your sister! Oh my God.” Seriously, variations of this scenario have played out several times.

At a particular moment in history, my sister Toni was the well-scrubbed, cheerful bourgeois face of hippie knowledge on natural methods of pregnancy attainment and avoidance, which is to say methods whereby a woman can ascertain whether or not she is fertile on any particular day and behave accordingly. (“And it’s not the rhythm method,” as she will always immediately insist.) Over the period of a few decades, science had been ratifying and further honing various folk insights, and Toni was there when the moment came to broadcast the news of full validation to the world. Her book, Taking Charge of Your Fertility, was an instant bestseller and has remained so ever since. I just looked it up, and as of today, Toni’s bright and cheery volume is the number #1 book on Amazon in the Fertility section, and number #2 in Sexual Health. For many many years, it was outranking Our Bodies, Ourselves. People love the book: she has over 4,000 ratings. Average: five stars. Ask any of your friends who are trying to become pregnant: She’s a rock star.

*

As is our mutual kid brother, Ray, albeit across a somewhat more circumscribed terrain. (There’s another brother as well, Robert, who’s also pretty terrific, but I will set his celebration aside for the time being, since I don’t want to grow completely obnoxious with all this familial kvelling, but don’t worry, I will trot him out on other future occasions.) Berkeley-based, my brother Ray is technically a lawyer though he has never practiced (one of his main part-time day jobs is as a self-employed librarian and legal-researcher-for-hire on the UC campus), but his true claim to fame, and indeed mini-mass adulation, is as the founder and curator of a weekly softball game, Sundays at eleven in the morning, usually at verdant Cordonices Park across the street

from the Rose Garden north of the campus (unless that field is closed for reseeding, in which case he shepherds his flock across a harrowing improvisation of alternative sites)—a game that has been going on, continuously, without interruption, for over twenty-five years: “The Finest Unaffiliated Email-organized Softball League West of the Sacramento River,” as he characterizes it, with typical bravado, or “Rayball,” as the rest of his community denominate the thing, for short. (Ray, incidentally, is exactly eight years younger than I am, having been born on my eighth birthday when the family was living in southern France for a year while our professor father was serving a Fulbright stint at the University of Toulouse. Since the baby’s imminent arrival pretty much ruined my own fervently anticipated birthday festivities—as I blew out the candles on the cake in a rushed ceremony at 6:00 a.m., my mother crumpled in pain and was rushed off to the natal clinic—I got to name the mewling newbie a few hours later by way of recompense and chose the name “Raymond” in honor of the famous and legendary and occasionally infamous counts of Toulouse, who on their better days served as patrons and lieges to the splendid troubadours of Languedoc.)

Ray’s game marshals a constantly shifting roster of players, of all levels of ability (from semi-pro to borderline hopeless) and gender (even a trans now and then) and background, ranging from age 14 through 79, featuring a wide range of professors (biochemistry, physics, zoology—snakes!—law, philosophy) and undergraduates and marginally employed passers-by and plumbers and janitors and electricians and waiters and waitresses and actors and artists and even a mother-and-son duo. “We’re way too old, white, and male,” Ray concedes, “but we’re always on the prowl for fresh talent. Just not old, white, and male.”

Anyway, key to his stewardship of the game are the Tuesday-into-Wednesday midnight e-missives in which he summarizes the previous Sunday’s match (judiciously skewering any laggards in a tangy zinger broth, begrudging the occasional and much-prized compliment, foregrounding new developments in the ever-so-nuanced ever-evolving community rulebook) and then positively grovels for folks to sign-up for the next game. These letters are so reliably faux-learned and drollarious that hundreds of people all around the world subscribe to the weekly drip for the sheer cock-eyed savor of it all—including an employee of the Swiss embassy in North Korea, I kid you not (where I really wonder what the censors make of each fresh weekly arrival). Once he has managed to gather up the requisite quorum of twenty volunteers, he painstakingly divvies up the teams himself (in a deliberative process that sometimes consumes entire days)—he always insists that he would much rather his own team lost by one than won by twenty (or even two), and whenever there’s a blow-out he invariably tenders his resignation in a near-Japanese ritual of self-abasement, an offer which is just as regularly gets refused, or so he assures us (or maybe he was just being rhetorical all along, it can be hard to tell).

The game is catnip for local journalists and can bring out the best in some of these would-be Angells (see for example, here, by, I am proud to say, a former student of my own!) and has even served as the backdrop for several short documentaries (including most recently this one of Kim Aronson’s).

To give you a flavor of Ray’s epistolary style, veritable troubadour of haplessness that he has become, there’s this, from a few weeks back, chosen almost at random:

June 1, 2022

Dear People,

Let me cut to the chase: I just checked our official community logs because something was gnawing at my emotional innards, and sure enough, it’s in those files that I found the roots of my despair. The fact is that Chris Fure’s team dominated my own last Sunday, 20 -13, but that’s just one pissant match and is neither here nor hare. The real problem is that on further inspection, I discovered that my own teams have now lost eight of the last ten, and in all candor, I was too tremulous to look any further into the past.

Indeed, if it became known that this grotesque pattern dates back to last winter, or 2004, or even to our communal birth in the 1880s, then my ability to continue serving as a team manager would inevitably crumble under the bitter defiance of all those future players who’d find themselves stuck on my side. Needless to say, such behavior would not be sustainable, and thus it was with a grave-looking demeanor that I decided to totally destroy all of this league’s digital records. You can now move on to other concerns.

Of course why my win-loss record is what it is is far from clear, for as we’ve recently discussed, contradictory drivel from Aristotle and Calvin to Hegel and Heisenberg makes fairly obvious that nobody has any real idea as to why anything happens. For example, Chris Fure is, to be sure, no “better” a captain than I am, and indeed, it wasn’t me that found himself running around like a beheaded chicken on Ritalin when no fewer than three of my peeps hit fly balls over his headless little poultry-neck, and for that matter, it wasn’t Chris, but me, who unleashed a glorious blast into the bush-laden tundra beyond deep center right (which I’m pretty sure is the first time I’ve done that since the creation of the universe).

Yet there it was, that annoying 20 -13 score with all its loaded connotations of winners, losers, and the mathematics of supposed superiority. Honestly, the whole thing reeks of corruption, the death of free will, antisemitism and even spooky kinesiological action at a distance, but sure, I can’t “prove” any of that, and therefore there will be a game at Codornices this Sunday at 11, IF I get enough commits by this Friday morning . . . Raymond

(Incidentally, those of you who might like to sample further such efforts, he keeps various files comprising the entire twenty-five-year run of the series online, and the most recent digest, going back to 2015, somehow escaped his digital conflagration and can be accessed here.)

I say, “almost at random,” but not really, because I chose that sample to set up this next one, which indeed launches our next section.

* * *

Dire Lists of Things Truly Worth Worrying About

Alas, Ray’s teams continued losing with truly unsettling regularity, and a couple Tuesdays later, he sent out this abjectly alarming email:

June 15, 2022

Dear People,

I’m not going to sugarcoat it; I had thought that good things would come from just coming clean the last few weeks and fully conceding how bad my win-loss record has been over the past several months. Indeed, I assumed that by metaphorically splaying myself nude before a shamelessly vulturine audience such as yourselves, it would give me the liberating moral fillip I needed to propel my captainships to new and rarified levels of excellence. Well, needless to say, that plan sucked, for Chris Fure’s team still obliterated my own, 19 -10.

So yeah, we all have to worry about inflation and bear markets and Ukraine and Taiwan and supply chains and AK-47s and baby formula and crime and homelessness and the stupid Hayward Fault and NIMBYism and the fragility of American Democracy and the inexplicable cult of that vile orange wanker-weasel and Covid and Fox News and gridlock and climate change and AI and the singularity and Kim Jong Un and deep fakes and oligopolies and the Borg and the CCP and the Middle East and the imminent Las Vegas A’s and wokeness and the ’22 midterms and wildfires and the ubiquity of bullshit and the end of Roe and the dearth of sleep and existential despair and suffering and dogmatism and irrationalism and Marjorie Taylor Spleen and the Sixth Extinction and aging and fentanyl and Nickelback and post-modernism and ultracrepidarians and the basic human condition and civilization-extinguishing meteorites and, of course, the utterly insoluble nature of both why and how we even exist, but at the end of the day, my teams have now lost 10 of the past 12, and so with all due respect, my solution-seeking priorities may not cleave to yours.

And therefore there will be a game at Codornices this Sunday at 11, IF I get enough commits by this Friday morning . . . Raymond

Not bad as such inventories of despair go, though almost immediately I got an email from fellow Rayball aficionado Walter Murch which read, in its entirety, “He forgot microplastics.” Others, Ray tells me, chimed in with further suggestions ranging from triggerhappy police and right-to-lifers and Sarah Palin and Bigfoot and the Illegitimate Supreme Court through the Suwalki Gap. (Good idea that: just toss the illegitimate Supreme Court into the Suwalki Gap and let them stew there.) And, oh yeah, Putin!

But then community veteran Jay Jurisich (who’s actual real-life day job consists in helming an agency called Zinzin, for the etymology of which see here, that comes up with names for start-ups and other such corporate entities, an expertise for which he gets paid good actual money) weighed in with this truly impressive inventory of things that might keep him up at night if he “weren’t so busy sleeping after yet another hard day making lists like this.”:

glass eyes that fall out unexpectedly

amateur prostate biopsies

flesh-eating bacteria

defecation in space

worms that climb up your urethra

brain infections

Republicans

raw-meat tasting menus

poison oak

botched adult circumcision

mass public liposuction

toddler infiltration

zip code malfeasance

being rubbed the wrong way

being accused of a crime I did not commit

hemorrhage, hemorrhoids, diarrhea, rhabdomyolysis, and all difficult-to-spell

syndromes with silent “h”s in their names

liquefaction

dust mites

earwigs eating into my brain

cat getting my tongue

a big bite of gristle

resisting the urge to plunge my hand into a running garbage disposal

the hole in the ozone layer

ISIS crashing my wedding

funerals

turpenoids in my gin fizz

male pattern baldness

a weird lump that won’t go away

murder hornets

intractable calcium deposits

wheat germ warfare

getting locked in a walk-in refrigerator

being eaten alive by pets after all the food has run out

spontaneous combustion

choking to death while laughing

my brother

rogue weed-whacker self-attack

table saw accidents

eye drops

confusing super glue for eye drops

passing out drunk and drowning in my own vomit

intestinal parasites

coughing up a hairball

vomiting blood

blood in the stool

the word “stool” and not the one you sit on

comets heading straight toward the earth

superfund sites

tsunamis

authority figures

ceramic figurines

tchotchkes in general

being tied up with barbed wire

biting off my own tongue

electrocuted in the bathtub by a small appliance

not being able to find a toothpick when you really, really need one

falling into a fast-moving river above a massive waterfall

owing the Mob a lot of money

discovering a charming resort in the remote countryside that turns out to be cartel

headquarters

classic rock on every radio station 24/7

AM radio

sports talk radio

my lipid panel is through the roof

hoof-and-mouth disease

biting off more than I can chew

walking and chewing gum at the same time, but then getting hit by a bus

I just went to the gym to get healthy and now I have rhabdomyolysis

the surgeons amputated the wrong leg

walking on the tarmac and getting sucked into a jet engine

running a marathon through a haboob

organized religion

disorganized religion

religion

black mold

vegan ice cream

gluten-free pizza

semen in the rice pudding

condo collapse

colony collapse disorder

a mild case of Ebola

plantar fasciitis

the massive black hole at the center of the galaxy

shopping malls

being mauled by a grizzly bear

being eaten by a shark

eating a shark

a meteorite plunging through my living room ceiling and hitting me

plate glass from a skyscraper falling on me while walking in a city

supply chain disruptions

falling onto the subway tracks with a train approaching

diving into the ocean and hitting head on rock

total paralysis

being deaf, dumb, and blind, but nobody writes a song about me

being mistaken for dead and locked in a morgue drawer

televangelists

getting a severe cut in a salt mine

being waterboarded with Budweiser

North Korean nukes

RBG not retiring and then dying during a Republican presidency (too soon?)

the water at the beach receding quickly and people saying, “Look, free fish”

a razor blade hidden in my toothbrush

Arctic heat waves

Antarctic ice shelves breaking off

ocean acidification

having to retake the SAT test every year

a zipline into an active volcano

hearing your lover yell during sex, “Stop the Steal!”

cold wars becoming hot wars

nuclear reactor meltdown

a bathtub full of potato bugs

all sports being replaced by football (and not the soccer kind)

all sports being replaced by soccer

forced lobotomy

being locked away in a Russian prison

being Black in America

needing an abortion in America

just living in America

At which point he signed off, jovially,

Cheers,

Jay

Indeed. And good night and pleasant dreams to you, too, Jay!

Meanwhile, Ray’s teams started winning again, so far two games in a row. So we can all relax after all. (Except that—this just in as of this past Tuesday’s midnight missive—his team lost again last Sunday. Uh-oh.)

***

From the Archive

Time was that I used to love baseball, followed it religiously, and adored going to games. But then, how could I not have, growing up in the early sixties in the Los Angeles of Sandy Koufax’s Dodgers? To me in those days, the most astonishing thing about my eminent Weimar-era émigré composer grandfather, Ernst Toch, was that he, for his part, had never even heard of Sandy Koufax. (What was wrong, what planet had he come from, anyway?) After our father (the Fulbright professor) was killed (the passenger in a car crash), two years after our return from Toulouse (I was ten, Robert eight, Toni six, Ray two, and our mother only thirty-three), several of his colleagues from UCLA began taking turns escorting me and then Robert to Dodger games (each time one or the other so that we could both get to enjoy feeling special)—and Robert really must have been something special:

he ended up attending two of Sandy Koufax’s four no-hitters, including the perfect game! (I took the injustice of it all a little hard, but I think that with the slow, healing passage of time, I’ve almost gotten over it.)

At college in Santa Cruz I was on the Classics department softball team, the Athanatoi (the Immortals). Each of us sported a jersey with our team name on the front and our specific Olympian designation on the back. We had Apollo as pitcher and Chaos as catcher, Hermes was shortstop, Tantalus manned center field—and I was Pan, the goat-footed right-fielder. Not much of a fielder and even worse as a batter. But somehow our team as a whole gelled. We didn’t have cheerleaders but we did have a trio of gossamer-draped dryads cheering us on from the sidelines—our friends Diane, Therese and Noelle, the Fates as they liked to fancy themselves—and Ian, the shy lanky-tall star Classicist with the enormous Adam’s apple would awkwardly sit out each game, picking dandelions, but then during the seventh inning stretch lope out to the mound to sing the saga of the game thus far, in Homeric hexameters! During the last inning of the final game of the season (against the Lit Grad students), we were behind by one point with runners at second and third and down to our last out when the Olympian at bat hit a lazy pop fly to shallow left, most likely an easy out and our impending doom, but then one of the Fates (it was probably Therese, it would have been just like her) got up and started shouting “Fuck you out there in Left Field!” and, sure enough, the poor Grad student in question dropped the ball, two runs scored and we won the game and the Lit grad students registered a fierce protest: how were any of them expected to be able to catch the ball with one of the Fates, of all things, hurling expletives their way?

Anyway, back in LA after college, I fell in with a group of friends who regularly gathered in the unassigned general admission seats in the topmost upper decks behind home plate at Dodger Stadium (only $2.50 per ticket). It didn’t matter what day you went, you’d likely find part of that cohort already taking in the scene and cracking wise. Hard to imagine such larkish spontaneities nowadays when ticket prices have exploded and hot dogs go for fifteen dollars and beer cups for twenty. It’s just not the same.

But aye, there was a time, and some of that time’s tenor gets reflected in this early piece of mine that ran in one of those local weekly free papers that got tossed in bales onto the sidewalks outside liquor stores, to wit:

The L.A.Weekly

Friday, May 25, 1979

BASEBALL BEARINGS

Why the National Pastime Strikes So Close to Home

Like any art form—for that finally is what we are dealing with—the cockfight renders ordinary, everyday experience comprehensible by presenting it in terms of acts and objects which have had their practical consequences removed and been reduced (or, if you prefer, raised) to the level of sheer appearances, where their meaning can be more powerfully articulated and more exactly perceived. The cockfight is "really real" only to the cocks—it does not kill anyone, castrate anyone, reduce anyone to animal status, alter the hierarchical relations among people, or refashion the hierarchy; it does not even redistribute income in any significant way. What it does is what, for other people with other temperaments and other conventions, Lear and Crime and Punishment do: it catches up these themes—death, masculinity, rage, pride, loss, beneficence, chance—and ordering them into an encompassing structure, presents them in such a way as to throw into relief a particular view of their essential nature. It puts a construction on them, makes them to those historically positioned to appreciate the construction, meaningful—visible, tangible, graspable—"real," in an ideational sense. An image, a fiction, a model, a metaphor, the cockfight is a means of expression; its function is neither to assuage social passions nor to heighten them but, in a medium of feathers, blood, crowds, and money, to display them.

—Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures

The past few weeks—the subsiding of April, intimations of June—have brought me back to first things, to primary knowledge . . . to baseball.

I've been thinking about the way baseball, much more than, say, football, serves as a figure for American life, how it is precisely this figurative aspect that renders the game so engrossing.

The game unfurls at an utterly leisurely pace; there is endless time to daydream, and the game itself spawns reverie. Baseball functions as a social figure, or fiction. It is continually playing itself out as if it were a metaphor. E.g., Dodgers down 5 to 1 in the eighth, bases loaded, and Ron Cey hunkers down and uncorks a grand-slam. In our reveries, this is almost an archetypal figure for "coming through under pressure." Our daily lives are rife with situations—striking out, balking, bobbling a grounder, arguing with the umpire, pulling off a double play, hitting into a double play, taking a base on balls, fooling the batter, robbing the opponent of an extra-base hit, being caught looking, blooping a single, fouling out, tagging up, whacking a home run—for which baseball provides an image, a referent. Failing to enchant a would-be paramour is just like striking out (but maybe you'll have another chance at bat—eventually, of course, you're hoping you'll score). Each new game is an utterly new experience, partly because we have lived an additional twenty-four hours and therefore bring twenty-four fresh hours of experience to the occasion, experience just waiting to be ordered, to be daydreamed into order.

*

One of the reasons baseball is so good for this (in a way football just isn't) is that it is a one-on-one sport within a social setting—and as such, it's just like real life. Boxing, for example, is a one-on-one sport of unmediated intensity: The myth of boxing is one man wedged off against another, nonstop, for the entire duration. Football, on the other hand, is an utterly social sport: It is never one against one; it's not even eleven against eleven; it's more like forty versus forty, or even beyond that, one entire team organization against another. (In this sense, football provides a superb figure for technological America, the kind of America that mobilizes to send a man to the moon—consider, in this context, the way "Disco Star Wars" was continually being used a few seasons ago as the musical backdrop for the late-night TV football wrap-ups. This technological aspect, as has often been noted, accounts for why football is so superbly suited to television and its capacity for instant replay. An instant replay of a great pass play, seen from different angles, provides a variety of insights into the technical competence of twenty-two separate players, each of whose contributions was central to the success or failure of the play. An instant replay of a grand-slam home run, on the other hand, cannot provide much new technical information: What it does is provide an instant reprise of the exhilaration of feeling—how it felt to watch that grand-slam sail out of the stadium. But you can get that as well or even better from the oral recall of a good announcer over the radio: It is the story, the fiction, the detailing of the situation and its outcome—rather than the witnessing of its technical execution—that is savored.)

Boxing is one-on-one. Football is forty-on-forty. Baseball, as I was saying, is something in between. Within a social framework, nine players on the field, a couple of players on base, it continually boils down to a personal confrontation, but one that is metastable, continually changing. The pitcher and the batter duel it out until finally the batter makes contact, then it's the batter and, say, the shortstop, the shortstop and the runner, the runner and the first baseman, the runner and the umpire. At any given moment, play is localized: It's not even one-on-one exactly, it's more like a series of individual challenges: the pitcher's, the batter's, the fielder's, the runner's. It is precisely because baseball addresses itself to a succession of individuals within a social context that it serves so well as a social figure, as an ongoing metaphor. You can't daydream into a football game: There is neither the time nor the occasion. Boxing, on the other hand, provides too intensive a figure: If a fan imagines everything in his life to be like a boxing match, "myself against the world," we account him somewhat paranoid. Baseball, on the other hand, provides us with a closer approximation of our lived reality. Watching it, we are replenished: It is a national re-creation.

*

Or anyway, so I find myself speculating in the stands at Chavez Ravine, one recent afternoon, as the game unfurls below. The sun is daft and breezy; the field, that miraculous integration of colors—cleangreen, skyblue, dirtorange—who'd have ever thought they'd blend so splendidly? My friend Dennis comes weaving down the steep steps, bearing beers. He's also brought some Crackerjacks, although we both agree that the prizes recently have been getting more minor league. I start unloading my latest theories on him, and, as usual, he dispatches them: Nonsense, he huffs, people come to the game because it's fun. Same difference, is what I think, but I let it pass. Play is tensing up down below—they've loaded the bases and Lasorda's ambled on out to the mound and now he's going to the bull pen. The bull pen's been pretty patchy this week and we've all got our doubts.

Baseball is forever the province of prepubescent boys, or those just barely poised on the cusp of adolescence, I find myself thinking as the new pitcher warms up. The players, no matter how mature or manly they are as people, as players are forever boys—in their pajamas! Football, on the other hand, is forever being played by high school seniors, jacked-up jocks who go out after the game and screw the cheerleaders under the bleachers.

In baseball, the manager suits up with the team, one of the boys—an old boy. In football, the coach paces the sidelines in a business suit, a corporate president.

Baseball is pastoral, football military. Football concerns the conquest of territory, baseball the longing for home. The baserunner just wants to get back home—how often, at the close of an inning, he's been "left stranded." Football may activate my adrenaline, but it seldom taps my melancholy.

By the way, I should make it clear that I myself don't play the game all that well. I've never been terribly well endowed in the athletic dimension. Back in high school, when they'd be choosing teams—the six head honchos divvying up the spoils—generally the selection process would run its course until all that was left was me and this legally blind kid and this other kid with a wooden leg, and the captain whose turn it was would look us over for what seemed like ever and then ask the coach if anyone was absent. Eventually I'd be the only one left and the coach would say, "Okay, Francisco, you get Weschler," and Francisco would whine, "But that's not fair, coach, we have fewer players than any of the other teams." That wasn't much fun, even though I was usually being pastured out to right field (except when a left-hander came to bat, at which point the left fielder would frantically rush over to trade places). I just liked it out there. That's another great thing about baseball: Everybody has room to graze. Nobody's crowding, nobody's huddled, wedged in tight, or scrambling together madly in pursuit of a bounding ball. Everyone has room to move around, get a sense of him or herself as an individual. When the play comes to you, it's your responsibility, just like it's your territory—maybe one person comes over to assist. Everyone else, grazing, gazing, has time to breathe.

*

And another thing about playing the game. Unlike most sports, in baseball there simply isn't that much difference between the experience of the seasoned professional and that of the rank amateur. That is, the feel of the sandlot game, to its participants, does not seem as removed from the feel of a professional match as would the feel of a game of touch football from that of a bout of professional caliber. Flagging down a crisply hit line-drive in center field—you pretty much know what that feels like the world over. Or anyway, so I like to think. Some Sunday afternoons, over at the field behind the local junior high where some of us play our games, I'm not so sure. When our team's fielding and the ball's ricocheting all over the outfield as the opponents keep toting up their runs—well, the phenomenological analogue there is more like what it must feel like to be a pinball machine—ding-ding-ding!

But sometimes even the Dodgers must feel like a pinball machine—that is, like rank amateurs. They're playing like that this afternoon, and Lasorda's out on the mound again. As imperfect as their performance has been, however, it does suggest another unique characteristic of the game. Because in baseball, perfection perpetually teases: It could be possible. The pitcher with an E.R.A. of 0.00, the batter with an average of 1.000, the game won on 27 pitches, the game won on 81 strikes. The batter who hit a home run every time at bat. The team that won every game. The perfect game. Indeed, baseball plays itself out within the bounds of a circumscribed, realizable ideal, always falling short by degrees, by percentages. No other game affords such precision, such clarity.

Numbers . . . and words. For as statistically intoxicated as the game is, baseball is also the ideal occasion for the inspired exercise of language—indeed, baseball is far more aural than visual, much better suited to radio than to television. And here in Los Angeles, we've for years been blessed with a master gameweaver in the person of Vin Scully. Tune in the radio at random most any evening: crackle, hone, and then the swell of that superb, familiar tenor twang. "Okay, here's Reggie. . . . Here's the pitch, and it's slammed, she's back, she's back, she's awaaaay back—she's gone!" Roar of the crowd, endless seconds of delirium, the sound finally ebbing as Vin's voice resumes, "There was no doubt about it: Lopes on third, Cey on second, Garvey on first, and Reggie walks to the plate, with standing room only, and he solves evvvverybody's problem!" Everybody's got their favorite Scully metaphor. I also loved that game last season when the Dodgers were stomping: By the bottom of the eighth, everybody on the squad had gotten a hit except Bill Russell, and as he approached the plate, Scully described him as "the only Dodger still outside the candy store."

*

I'm afraid as far as this evening's game is concerned, the Dodgers aren't even in the neighborhood of the candy store. The other team, meanwhile, seems due for an insulin fit any moment now. It doesn't matter. Twilight sets in and the game winds down. I try a few more insights on Dennis and he smiles fondly as he shoots them out of the sky. Baseball is about friendship.

* * *

BASEBALL-PERTINENT LEAVES FROM MY COMMONPLACE BOOKS

Samuel Beckett was taken to Shea Stadium for his first baseball game, a doubleheader, all explained by his friend Dick Seaver. Half way through the second game, Seaver asked Beckett if he would like to leave.

Beckett: Is the game over then?

Seaver: Not yet.

Beckett: We don’t want to go then before it’s finished.

--recounted in Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140

*

Which in turn reminds me of the time my Polish wife Joanna and I took her father Zenek, visiting us his first time in America, to Shea Stadium to take in our own Mets game. Zenek spoke not a word of English, and I not a word of Polish. Joanna sat between us. I would anatomize the developing situation out on the field with rising excitement; Joanna would translate in a level, steady voice; in response, Zenek would himself grow ever more excited and engaged; Joanna would translate in the same, level, utterly disengaged voice; I would rise to the level of Zenek’s excitement in my response; Joanna would drone the translation—and it went on like this for hours. Joanna was like a perfect superconductor: not a watt of the growing enthusiasm to either side rubbed off on her.

*

In a similar vein, the story goes that the German filmmaker Wim Wenders once asked a friend of his to take him to a ball game, so they headed out to Dodger Stadium, though as things turned out, a couple hours too early, even before batting practice had begun. Still, no problem: the only people in the stands, they’d settled in comfortably when over the PA System came a booming stentorian voice: “This announcement is for venders only.”

*

“Pitcher”

by Robert FrancisHis art is eccentricity, his aim

How not to hit the mark he seems to aim at,

His passion how to avoid the obvious,

His technique how to vary the avoidance.

The others throw to be comprehended. He

Throws to be a moment misunderstood.

Yet not too much. Not errant, arrant, wild,

But every seeming aberration willed.

Not to, yet still, still to communicate

Making the batter understand too late.

(Included in Baseball, I Gave You the Best Years of My Life, ed. Richard Grossinger & Lisa Conrad, 1978)

* * *

CODA

Which brings us back to Sandy Koufax, who, apart from everything else, many felt to have been just about the best thing ever to happen to Judaism in its American incarnation (certainly felt that way to a nerdy yid like me back in those, his glory days). He just radiated class and grace and modesty and circumspect self-possession, not least at that press conference when, at the very peak of his career, he suddenly announced that he was laying down his glove, and then pretty much disappeared into a zealously guarded retirement. The Dodger Garbo.

I was thinking about Koufax again the other day because recently he gingerly poked his head out of that circumspect reclusion to participate in a ceremony at Dodger Stadium, where out beyond center field they were dedicating a statue of him frozen in utterly commanding mid-hurl right beside that other one of Jackie Robinson forever sliding into home. Several speakers celebrated Koufax’s manifest magnificence and then he got up to say a few words. He’s eighty-five now and yet as snappy and dapper and joshingly self-effacing as ever. Many of you may not thrill to the little speech he gave—almost Zenlike in its egoless elevation of positively everybody else—but if you happened to have been young and alive in that town back during those years, you too may find his sheer graciousness almost devastating in the purity of its persistence. He was just about the coolest guy ever, and still is.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

Animal Mitchell website.

* * *

AND ONE FINAL IMAGE

Hmmff, look what I just found, burrowing through some boxes of memorablilia.

That’s the four of us kids—Ray, Toni, me, and Robert (with our mother Franzi)—two years after our father’s death in that car accident. It had gotten so that our mother couldn’t stand being on the receiving end of all the heartfelt pity and sympathy she was receiving in LA and so she took us all back to Toulouse, to the same charming little cottage we’d all shared four years earlier just outside town when our father was still alive and he was on that Fulbright year, the happiest year of her life, she’d always later say.

Years afterward, our grandmother Lilly (the composer’s widow and my mother’s mother) would describe in an oral history whose transcript I was asked to edit how Franzi had gone insane with grief and was dragging the kids all over Europe. There’s a bracketed comment after this passage on p. 872 of volume two of the bound transcript of her interview in the Toch Archive at the UCLA Library, which reads in its entirety: “[It wasn’t so bad. We were having a good time.—EDITOR]”

One of these days I’m going to have to write about my mother.

* * *

ENVOY

Oooof. That was a long one this time. In part though because it’s summer, and over the coming weeks Wingman David and I will be taking a bit of a breather. You’ll still be getting fresh issues every two weeks but they may be a bit more slender, because the two of us are going to be taking it easy. We haven’t even figured out precisely what we’re going to do next, but don’t worry, it’ll be cool.

In the meantime, though, those of you who haven’t yet, please do consider subscribing on a more regularized basis (the whole enterprise is still only hanging on by a financial thread), and more importantly, all of you, if you’ve been enjoying the Cabinet, please do make a point of telling you’re friends about it (it’s easy, just hit Share!).

You folks, try to take it easy, too, in the weeks ahead. It’s been an exceptionally tough year and we need to build up reserves to get through the rest of it!

* * *

Thank you very much for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time. We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com. And do please subscribe and share!