June 9, 2022 : Issue #18

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This time out, we begin with part two of our three-part conversation with digital magus Blaise Agüera y Arcas on the occasion of the publication of his remarkable first fiction, Ubi Sunt; whereupon the INDEX SPLENDORUM will host an admittedly somewhat snide but deliciously funny look at robots somehow failing to launch; following that up with the first (micro-macro cosmic) winner of our only-just-recently-revived CONVERGENCE CONTEST, even before we’ve had time to officially launch the thing, which we will thereupon proceed to do.

* * *

This Issue’s Main Event

A Conversation with Blaise Agüera y Arcas

(Part Two of three)

As we were saying last time out, Blaise Agüera y Arcas—the eminent software designer and engineer; world authority on computer vision, digital mapping, and computational photography; and, ever since his much-noted departure from Microsoft to Google in 2013, one of the leaders of the latter’s machine learning efforts—has been variously hailed as “one of the most creative people in the business” (Fast Company) and among “the top innovators in the world” (MIT Technology Review). He’s also a close friend, which is odd (and bracing) because we disagree so fundamentally on such fundamental things. For example, whether bots or any machine will ever be able to achieve anything like what we mean when we say “consciousness.” Last time, we started out by tracing the lineaments of Blaise’s upbringing, education, and stellar early career, before beginning to turn to his thinking on the current state of play in deep machine learning, the subject in part of his recently released novella (his first published fiction) Ubi Sunt. Along the way, our own disagreements began to clarify, as when I had recourse to the formulation of one of my own favorite philosophers, Nicolas of Cusa: his endlessly compounding n-sided regular polygon inscribed inside a circle, as anatomized in his 1440 magnum opus, Learned Ignorance. (“Reason stands in the same relation to truth as the polygon to the circle; the more vertices a polygon has, the more it resembles a circle, yet even when the number of vertices grows infinite, the polygon never becomes equal to a circle, unless it becomes a circle in its true nature.”)

LAWRENCE WESCHLER: No, as I told my fellow panelist that day [at the symposium I curated alongside David Hockney’s show at the De Young Museum in San Francisco in 2013], Cusa insisted that at some point you were going to have to make the leap from the polygon’s chord to the circle’s arc, the “leap of faith” as he called it (Kierkegaard got the phrase from him), a leap that could only be achieved by way of grace, which is to say for free. And that image has always struck me as immensely powerful in all sorts of contexts, working equally well if you strip it of its specifically religious context. As a way of talking about the brain and the mind, for instance— how no matter how detailed a picture you get of the brain, and that picture is getting more and more magnificently detailed every single day, you will still never be able to account for the miracle of consciousness through that route alone. There needs be all that, but then something more…

So I was yammering on like that, at which point you leaned over, sotto voce, and asked me, “Ren, you are a materialist, aren’t you?” and I replied, equally sotto voce, “Actually, no, I don’t think I am.”

BLAISE AGÜERA Y ARCAS: Yes, that was when I knew that we had an important difference.

LW: You looked completely abashed and you just kept looking at me for the rest of the panel as if I had sprouted a horn on the top of my head. (laughter)

BAA: Well, you had in a way in that moment. Yes. (laughter)

LW: Before we start talking about your new novella Ubi Sunt directly, you were telling me, that some of the “conversations” between the seeming narrator, who is kind of like you, and the machine with which he is interacting from home during his COVID-era sequestration, are straight out of what's actually happening right now. How is that different than it was a year ago? And how will it be different a year from now?

BAA: In the dark ages of AI, between 1957 and 2005 approximately, we still thought about two kinds of tasks. There were logical tasks and squishy tasks. Logical tasks are things like: calculate the trajectory of a missile, balance the books, evaluate that spreadsheet. Those are tasks that are hard for people to do, but trivial for computers of the kind that McCulloch and Pitts theorized, and which were soon built.

Because you can do them all with logical operations, and anything that you can do with logical operations, computers just kicked our butts at immediately. But a squishy thing, like being able to recognize another person, telling cats from dogs, transcribing speech in a noisy room…

LW: Because there are so many other sounds going on at the same time, and how does the machine make out which are the ones it has to isolate as the conversation?

BAA: Right, it's really hard to turn that kind of a task into something that looks like operations on logical predicates. The big revolution that happened between 2005 and let's say, 2015, was that these very large, deep neural nets of the kind we were talking about finally cracked squishy tasks like these. More or less anything that could be defined as a task with a clear goal and a clear way of measuring performance started to succumb to deep learning. These included things like speech and recognition of objects, but also playing complex games like chess or go, Atari games and beyond. But I sometimes use the metaphor of AI researchers being a little bit like the dog that caught the car— a long dreamed-for quest that once we achieved it left us wondering, What now?— because it turns out that real intelligence doesn't boil down to easily quantified, robotic tasks. That's not what we are.

LW: Hmm. Interesting: “what” and not “who.” Because something that we will speak about in some more detail as we go along is what is being talked about when people talk about the Singularity as in some sense the moment when the human and the robotic ways of being kind of converge. But in that regard, the question keeps arising as to whether computers are getting more and more “human,” or alternatively, it’s just that humans are becoming more and more robotic.

BAA: Yeah, I think the second one, too. The thing is, however, I don't buy the idea of humans and machines being separate in the first place. There's a dualism there that I think needs to be questioned.

LW: [pause] [long pause] Okay then. But let me ask you a question: Really? There's not a scintilla of non-materialism in you? (laughter)

BAA: I think the short answer is: not at all. Not a scintilla.

LW: Funny that you should say that, I was just reading Benjamin Labatut to the effect that the word “scintilla” goes back to Antiquity where it means “the spark of the soul, the divine essence that resides inside all living beings.” And you’re not having any of that?

BAA: I mean, obviously, humans and animals are messy and complex. We have all sorts of drives and abilities to both think brilliantly and to feel deeply. And to act irrationally. I don't mean that in a negative sense, either. The idea of rationality being something to be striven for, some sort of goal, doesn't make much sense when you look closely. I mean, rationality to what end? Without a well-defined end goal, who can even say what’s rational and what’s not? But yeah, I think that in recent centuries we’ve become more machinic, more Taylor-ish.

LW: Taylorism being the factory management system, based on the late nineteenth century doctrines of Frederick Winslow Taylor, that was designed to increase efficiency by evaluating every step in the manufacturing process and breaking down production into ever more specialized and mind-numbingly repetitive tasks. It was (and is) not pretty.

BAA: Indeed, it created a lot of the horrors of the Industrial Revolution. And they're the same horrors that are being visited upon Amazon warehouse workers today, who are essentially being made to behave like robots. Everybody knows that it'll be robots all the way through the warehouse in a few years’ time. So those workers are just kind of marking time there, damaging their bodies, doing the tasks of robots for a few years, while the robots get built and trained to do the same thing. Which is an inhuman use of human beings, as the cyberneticist Norbert Wiener called it.

LW: Taylorism cubed, basically.

BAA: Exactly.

LW: But another approach to the same sort of issues—and we've talked about this a bit—I’m wondering about the extent to which AI and computer people who are at the forefront of doing the kind of work we were talking about a few minutes ago, turn out to be people on the spectrum. For starters, would you describe yourself from the childhood you described as being somewhat on the spectrum in some sense? Just to be clear here, I’m not being judgmental in any way, I’m just trying to be descriptive— but are many of those who are particularly adept at doing this kind of thinking, coding, and the like, of a neurotype that experiences the world in a particular sort of way? Is that not a fair thing to ask?

BAA: I think that as a general statement, it's entirely fair, and I think it's even been quantified. The question of whether I'm on the spectrum? Well, let's put it this way: I think that I'm probably not entirely neurotypical: there's probably something not quite normal (laughter) about the way my brain works. But I don't think I’m on the autism spectrum. I say that because although I’ve certainly felt alienation throughout much of my life, I never had any of the physical symptoms, or the lack of affection, or any of that sort of thing. I don't feel like I have trouble with theory of mind in the way that autism spectrum people do. If anything, when I was younger, I was kind of overly sensitive, shocked by the lack of empathy of a lot of the kids around me.

LW: Do you find that there are people working at Google who you would describe as on the spectrum?

BAA: Oh, of course.

LW: And so coming back to the original thing that I was trying to get at, about how people are becoming more and more machinelike (as opposed to the machines becoming more human), with some of the people at the point of the spear in this sort of work, would the relatively high incidence of spectrum folk among some of the ones who are actually doing the hardest work at the human-bot interface, have any bearing on such a discussion? Would that be a fair thing to ask?

BAA: I don’t think that if somebody’s on the autism spectrum that that implies that they are more quote, unquote, machinelike. For me, what machinelike means isn’t just “can't relate to other people” or something. For that matter, the distinction between humans and other animals is one that I think is very, very thin. So let's take animals as a whole: animals are not things that are designed for doing a particular task, as a machine is. They have various competencies, certainly, and sometimes they can do tasks at a near-optimal level, for some rigid definition of that. When somebody describes a certain animal as “a killing machine” or something like that: it might be true that for a fraction of a second every other day or whatever, they can execute a perfect kill, but there's no way that you can say that this animal is a killing machine, other than colloquially. A killing machine is a pneumatic bolt in a slaughterhouse: I mean, that's what a killing machine really is. There is no animal that is a killing machine, or an anything-else machine. Even the simplest animals interact with all these other things in the world and do all kinds of stuff and feel in all sorts of ways.

LW: And importantly feel in those ways as individuals of the species as distinct from other individuals of the species.

BAA: Yes. And industrial machines don’t do any of that stuff.

LW: That reminds me of the great insight of Jane Goodall that we talked about the other day, how when she was starting out, she was told to give the chimps numbers…

BAA: And she gave them names instead.

LW: And when she gave them names, she started noticing things about them that it was impossible to notice when she only gave them numbers. And that was all suspect to her fellow scientists at the time. Still, it was very, very interesting.

But so, going from animals to humans to now machines, are you making an analogy that humans are no more separate from animals than potentially machines will one day be from humans?

BAA: I think that if you try to decompose what we mean by a human, there are a lot of different properties, a lot of particulars there. And you can start to tease some of these apart when you look at patients with brain lesions of different kinds. Then you discover that there is no single thing where you can say, You're a human because X: because you feel pain, say, because there are ones who don't; or because you feel empathy, because there are ones who don't; or because you can do task X, Y, or Z, because there are humans who can't do any of those tasks. And more broadly there's this—let me grab it—I don't know if you're familiar with this thing. But it's a little book that was designed to be hidden away, called L’homme Machine.

LW: What year?

BAA: 1730-something I believe. Anyway, it's an 18th-century thing. And I would say that it's kind of the urtext of materialism.

LW: And you sleep with it under your pillow every night? (Laughter)

BAA: (Laughter) I keep it under my pillow every night. Of course [Julien Offray] de La Mettrie, who wrote this thing (in 1747, actually), did not sign it, but even so he got discovered and was run out of town. He was originally a physician and saw a lot of injuries in the battlefield, including a lot of brain injuries. And it was really looking at brain injured patients, I think, that convinced him that the brain is a machine just as much as the rest of the body is, and this is where he departs from Descartes. Because for Descartes, the body is a machine, but somewhere in the brain, there's the pineal gland, you know, and that's the seat of Reason and hence the seat of the Soul.

LW: The Scintilla.

BAA: Yep. But La Mettrie is just noticing the obvious, which is that if different parts of the brain are damaged, you can damage any damn thing about personhood and intelligence. So when we talk about…

LW: But wait: first a few comments or footnotes here. I assume you've read Kazuo Ishiguro’s new book—

BAA: Yes, Klara and the Sun. Wonderful.

LW: And, as has been noted, in some ways the most human character in the story is Klara, the robot. But on the other hand, at the very end, she's displaying a very unhuman kind of equanimity over having been remanded to the junkpile. And I'm also reminded of Oliver Sacks, who, of course always said, “I'm not interested in the disease the person has, my interest is in the person who has the disease,” right? And one of his more wonderful comments is that “My subject is the intersection of fate and freedom.”

BAA: Yes.

LW: So fate are all the different kinds of lesions you could have. But what fascinates him is how specific individuals deal with those lesions. Which still leaves the question of whether you will ever be able to talk about the intersection of the fate and freedom of a machine.

BAA: Well, I have my own take, I suppose, on what that really means. Listen, I'm a big fan of Sacks and the stories in your book [And How are You, Doctor Sacks?] about all of this are wonderful. And I largely agree with Sacks’s perspective on it. But my take, I suppose, is as follows: A lot of what we rebel against in the idea that people are machines is the idea that the execution of a machine is machinic, right? That it's deterministic, that there's no freedom in it. That feels repellent to us. But the idea that determinism is deterministic, if that makes sense, is only really true in the simplest kind of Newtonian universe. If you have a handful of billiard balls and they're knocking around, sure, you can predict what's going to happen. In a real universe, though, you can't begin by saying, “Well, if I know the positions and the trajectories of everything, then I'll be able to predict what’s going to happen.” The whole understanding of dynamical systems that has emerged in the 20th century is that reality diverges exponentially from any sort of measurement of initial conditions. So the idea that determinism holds for a very, very complex system is problematic to begin with.

LW: Which reminds me of Errol Morris’s short film The Umbrella Man—have you seen it?

BAA: No, no, though I like Morris’s work.

LW: Well, it’s about seven minutes long and you really must give it a look—for that matter, readers of this eventual transcript should just stop whatever they are doing and watch it at this point.

It’s only about seven minutes long, and its principal narrator is Josiah “Tink” Thompson, who quit his job as a tenured Kierkegaard professor at Haverford to investigate the Kennedy assassination, culminating in his masterful study, Six Seconds in Dallas, but at the outset Morris has Thompson citing a Notes and Comment piece from The New Yorker of December 9, 1967, in which the anonymous contributor, who turns out to have been John Updike, basing his speculations on Thompson’s work, went on to marvel at the way that history at the macrolevel might be seen to obey various Newtonian sorts of rules but the closer and tighter you got into probing the specific details of any and every specific microincident, such rules break down completely and it’s as if everything goes all quantum.

BAA: Well, that's true of course, but even the idea that when you zoom out, it becomes more Newtonian or predictable: That certainly holds for thermodynamical variables, temperature and the like. But—But—I think that's different for living things. And I think this has everything to do with our sense of freedom and liberty, or what Daniel Dennett calls “elbow room.” We really, really prefer not to be predicted. And I think that that has deep roots in the way animals are with each other. They (and we) don’t want to be predictable. You don't want to be predictable to your lover, you don't want to be predictable if you're a predator, and you definitely don't want to be predictable if you're the prey of that predator: it's a life-or-death thing. You want to be able to zig this way or zag the other way, keep them guessing. You basically keep yourself in indeterminate states. That means you aren’t even entirely predictable to yourself! Hence, free will. If you want to think in terms of quantum collapse, you keep yourself “uncollapsed” in the process of doing things, and when I say “you keep yourself,” I mean evolution has so designed us such that we prefer those situations. Rats aren’t alone in not wanting to be cornered. I don’t mean that we literally rely on quantum mechanics, but rather that we seek to keep a bubble of uncertainty inflated around the models we build of each other, and even of ourselves.

LW: And are you saying that we will one day be able to program machines to be like that, or that they by way of their own evolution will become like that for the same reasons?

BAA: We’ve barely started to design and train neural nets under anything like truly social conditions. You know, when they're just doing tasks, whether those tasks are industrial, like spreadsheets, or more squishy, like recognizing images, it's still a single purpose thing. But what’s different about natural dialog systems of the sort that get illustrated in Ubi Sunt (and the actual dialogs that are the basis for those conversations) is that they're not really trained for a specific task. The great majority of the training is “unsupervised,” meaning that it's just taking in lots and lots and lots of text. Including lots of conversation between people.

*

LW: So we've now arrived: That was a fast five minutes. (laughter) We've now arrived at you, for the sake of discussion, at the beginning of 2021, and you are working on some of these investigations of the deep learning of language and conversation and so forth with these wide neural nets. And you're working at home, because Google has shut down its main offices, like everybody else has, on account of COVID-19. So that now we can really begin to talk about this Ubi Sunt text of yours.

And one of the things that you were feeling already then was the sense of the Before Times and the After Times. I myself have been thinking in the same terms, using the same language about the Before Times and the After Times, meaning before COVID arrived and after it will be over, and how the one will be different from the other, and how the present In-Between-Time has been so very weird in itself. Though in your case, and arguably just by coincidence, language work in your field was tottering in a similar way between Before and After Times in the very midst of the COVID stasis, which provided you with the germ of the idea for this fiction—would that be a fair way of characterizing things?

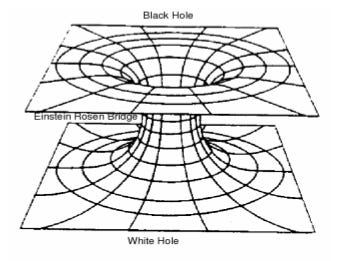

BAA: Yes, that's right. We've all been feeling something like this sense of passing through a bottleneck, or a birth canal, perhaps. And that reminded me actually of a famous diagram (reaches for something)—in this brick of a book called Gravitation (Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler, 1973). It's a book that warps space around it, for sure. And in the black holes chapter in this thing, which is one of the better ones, there's a very famous diagram of the Schwarzschild geometry of black holes. And it looks like a birth canal. Here, I'll find it in a second. Page. 817, it must be close to there. Yeah, this:

Here we go. You’ve seen these kinds of pictures.

LW: Of course.

BAA: So here the Before Times and the After Times translate into outside the Event Horizon and inside the Event Horizon (otherwise known as the Schwarzschild Radius)—that uncanny geometry. And, of course, what happens at the Event Horizon…

LW: The Event Horizon in that sense being the point of no return on the rim of a black hole, such that once you've drifted that far, you're not coming out—

BAA: —yes, and what happens is that you stop being able to talk about space and time as different coordinates, the spacelike coordinate of “inward” becomes a timelike coordinate, and the difference between the two collapses, or rather stops existing. And it struck me as a really rich metaphor for this weird moment that we're in right now.

LW: Right, we’re emerging into a different universe.

Anyway, so you yourself are doing that kind of thing and—being the playful person that you are, the sort who spends his time in the Princeton physics department playing with pre-Gutenbergian font sizes and so forth, that kind of guy; and also being a littérateur, somebody who reads all the time and savors the reading—you take up the idea that you're going to create this fiction. Is it unusual for you to do fictions? Or have you done others over the years?

BAA: No, I've done very little fiction. I've started a small handful of projects, but this is the first one that I finished, at least in many, many years.

LW: So now, give me the elevator pitch of the fiction that you've created here.

BAA: Oy. Well, the elevator pitch is that this novella is broken into three parts that are interleaved. It's sort of the outer universe, the birth canal, and the inner universe, or the Before Times, the During times, and the After times. The During Times take place in the first person present tense, and they’re about a character who is sort of like me, though of unspecified gender, in this moment of working on chatbot AIs, which is to say neural nets that have been trained for conversation. And, in particular, trained in this new way in which the overwhelming majority of the training is unsupervised, meaning it's not really specific to a task, which I think is critical. Right? So it's post-industrial, if you want to think about it that way.

LW: And this is what a GAN is, right?

BAA: Well, a GAN is a Generative Adversarial Network, and actually those have not been used yet in any chatbot I know of, although I'm sure it’s just a matter of time.

LW: And what are they?

BAA: A Generative Adversarial Network is a kind of network or network pair, really, designed to generate art. There's an artist and a critic, and the two are in an adversarial or cooperative relationship.

LW: You mean a notional artist and a notional critic, they are programs in a sense, or they are chatbots, or what are they?

BAA: They're neural nets. Synthetic brains, if you like. The artist is trying to generate media. And the critic is trying to distinguish the media that the artist generates from the real thing. So you have to have a large stack of real things, whatever the real thing is. And the artist begins by babbling, begins by generating nonsense. And the critic begins by not knowing the difference between nonsense and the real thing. But they both ladder up together: as the critic becomes better at distinguishing, it gives feedback to the artist. And as the artist gets better, it produces more and more convincing versions of reality.

LW: So this is the kind of thing where ordinarily you get them going, you go home for the night, you lock the door behind you, you let them play for a while, you come back in the morning, and you see what they've done?

BAA: Yes. And they both have gotten more interesting. Usually you're looking at the outputs of the artist. You know, if you've seen any of these deepfakes that have very convincing faces, generated by neural nets—those are the things that get generated by the artists, when you have them generate lots and lots of fake faces, and the critic is trying to distinguish fake faces from real faces.

LW: And my impression of it, based on some of your TED talks on the subject, is that it can get to looking like the internet is dreaming, that quality of it's just being very fluid, with things appearing and disappearing.

BAA: Beautiful and uncanny, right?

LW: It is mind-blowing.

This entire Ted talk of Blaise’s is fascinating (some of it recapitulates some of the issues we have been discussing here). All of it is worth viewing, but the specific dreamy and mind-blowing section begins at approximately 11:50.

BAA: Deep Dream and things like it are generative models, a bit like the artist part of a GAN. The psychedelic stuff in that talk wasn’t honed against any critic, though. Hence trippy.

LW: But the thing that you're doing right now, those language things that are happening, what are those?

BAA: Think of those as just the artist part. Though not for images, but for dialogue, for text—

LW: And who then is the interlocutor with the machine artist?

BAA: Well, I'm imagining a mash-up between GANs and these kind of language generators. Suppose there's both a language generator that is playing the role of the artist in a GAN and also a language critic trying to distinguish reality from forgery.

LW: So that this leads to—and spoiler alert here, only because: beats me—the first… Or let me put it this way: All the way through this text, what one is trying to figure out at any given moment is who is “I” and who is “you” and who is “we,” and so forth. And it certainly feels like at the beginning there is an “I” who is the person we associate with you, Blaise, who is worried about your parents and their COVID exposure, who has a physical trainer, who gets pissed off about this or that and has very deep philosophical thoughts that are kind of interesting, or who gets bored, and then at a certain point tries to close the lid on his (or her) laptop so they can get some sleep, but can't bring themselves to keep away from it.

BAA: Yes.

LW: And it seems at the beginning that the conversation is between the neural net as it churns away and that person.

BAA: Yes—

LW: And that’s not because I'm a hopelessly naïve projector of my own humanoid biases, that's how it’s really meant to be read at the outset?

BAA: Yes, that's how it's set up.

LW: But…

(TO BE CONCLUDED IN OUR NEXT ISSUE)

NOTE:

Blaise’s novella Ubi Sunt is officially out from Hat & Beard Press in Los Angeles and can be procured at a 20% discount from the publishers directly if you take advantage of this link, where you will also get a sneak preview of the book’s remarkable design, and where, too, the $25 dollar book will register as $20 as you check out.

* * *

From the INDEX SPLENDORUM:

COLLAPSING ROBOTS

I realize this is a bit of a cheap shot, in light of the foregoing conversation across which Blaise seemed to be projecting such apparent optimism with regard to the future prospects of machine intelligence. But all the while as we were talking, I found myself internally humming the musical theme from this compilation video from 2015, in which robots are taking part in a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) competition, whose main challenge, as I recall, was the ability to approach a closed door, reach out to its handle and open the thing. Instead they kept falling all over themselves, often spectacularly. All set, as I say, to an inspired musical accompaniment. Enjoy.

* * *

REVIVED CONVERGENCE CONTEST:

FIRST WINNER!

Over the past several issues we’ve been signalling the imminent revival of the Convergence Contest that I curated on the McSweeney’s website for a while after their 2006 publication of my Everything that Rises: A Book of Convergences — to which the recent “All that is Solid” series here (Issues 11 through 15) was a sort of sequel.

Well, we haven’t even had a chance to frame the rules, and I’ve already received an initial submission from my longtime friend Tristan de Rond, a Dutch biochemist recently transplanted (with wife and new baby) to Auckland, New Zealand. Was this, he wondered, the sort of thing we had in mind?

On the left, an electronic microscopic image of a protein ring, prized by a team from the Max Planck Institute in Mainz Germany in April 2019; and on the right, an unprecedented image capture of a black hole, in flagrante, released the day before by the team behind the Event Horizon radio-telescopic array.

Holy Cosmic Cat Eyes, Batman, you bet it was!

But what, we wondered, were we being invited to make of this? (In general, and in the future, convergent contest entrants should include not only a visual or other sort of rhyme but also a paragraph or two—kind of the poem around the rhyme—fleshing out some of the wider potential implications behind the convergence.) I wrote Tristan, and Tristan replied, for starters, with the complete Twitter thread by which this particular rhyme had first been launched out upon the world by Stefan A.L. Weber of the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Mainz, Germany. It began with those dual images, followed by a sequence of tweets, by way of explication. To wit:

April 12, 2019

One day after Event Horizon announced their picture of a black hole, we finally managed to image a protein ring using AFM yesterday — there is a factor of ten sextillion (10^22) between the scalebars of those two images.

NOTE: We asked Tristan where, in the progression of 22 magnitudes, an ordinary single meter would fall, and he replied “Well, 100tm = one hundred trillion meters (1x10^14 meters), and 50nm = 50 billionths of a meter (1x10^8 meters). So the one-meter scale is 14 orders of magnitude down from 100tm (the black hole) and 8 orders of magnitude up from 50mm (the protein ring).”

April 13 [continuing with Weber’s Twitter thread]

Now that this image is becoming famous, maybe some of you are interested in the story behind this. I am a scanning probe microscopist and I usually investigate how charges are shuffled around in nano-solar cells.About two years ago, a colleague from the biochemistry department at Uni Mainz approached me and asked if we could resolve the structure of this peculiar plant protein. It seems to be essential for photosynthesis, but how exactly it works is still unclear.

In particular, the structure was unclear. Electron microscopy suggested a ring structure, so we were looking for a ring. But all we could see was blobs or fuzzy aggregates. We were already sure that the protein simply does not aggregate in a ring shape.

Recently, we discussed all this with a colleague with more experience in imaging proteins with atomic force microscopy. We sent him some protein samples and one week later, he sent us images—with perfect ring structures!

Frustration. We had tried for more than a year and never saw rings. Okay, we’re the new kids on the block of protein imaging, we thought. But then we looked how exactly they had done this. Apparently they used the “wrong” buffer with the “wrong” salt concentration.

“Wrong” because we thought that at these concentrations the protein would simply not be stable. So we tried under those conditions, too—and saw rings! What exactly that means, we still need to figure out, but we’ll keep you posted!

All the credits for the image goes to Benedikt and my PhD student Amelie Axt.

Some of you asked what Protein this is. It’s called IM30 and it seems to be essential for photosynthesis (without it, cells die). We work together on this project with the group of Dirk Schneider, Biochemistry at Uni Mainz. For more info on IM30, make sure to follow them: @DSchneiderLab ! There’s also a preprint available showing how IM30 can do funny things with biomembranes in the presence of magnesium salts.

Well, alright then. I tried to reach Stefan Weber to ask him what he made of the uncanny convergence, but for a while we didn’t hear back and time was a’wastin’, so instead I followed up with Tristan:

Very very cool convergence, but what does it mean? (First of all, congratulations on your own very very small new fellow creature, and amazing the gravitational impact such an arrival can have on all the relatively more massive creatures all about her). But returning to those cat’s eyes of images (especially set side by side like that), or maybe, shall we say that parallel floating orange doughnut effect, I’m of course reminded of Heisenberg’s great comment: “We have to remember that what we observe is not nature herself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.” And what I wonder is whether that pairing turns out to be about how similar Nature turns out to be at the two extremes, or rather how similar are the limitations of our technologies (our methods of questioning) at the two extremes…

To which Tristan replied:

Thanks, Ren! I didn’t know that Heisenberg quote, but it's great! Certainly the artifacts and blurriness of the images arise from similar limitations in our observing technologies, but I think the "doughnut" shape similarity is honestly more of a coincidence. The proteins are actually arranged in that shape: the image is imperfect but it's a "true" representation of the same. I don't have enough imagination to wrap my head around what the "true" shape of a black hole is, but it's definitely not what's in the image because the black hole is bending light around itself such that the image looks different (parts of the black hole image are actually coming from the far side of the black hole). With risk of invoking something I know even less about: maybe the Force Microscopy picture is like a Realist painter with an inconveniently large paintbrush, while the black hole picture is like a Cubist painter trying to show its subject from multiple perspectives in one representation.

Ah, so maybe not so cosmically portentous a pairing after all. Though no less cool for all that. Wingman David chimed in as to how all this put him in mind of the lyric his old pal Ken Kesey used to cite (from a Burl Ives song). “As you go through life make this your goal, watch the donut, not the hole.” (And then we did hear from Stefan Weber after all, though too late to fold his entire missive into this presentation. But you can access it here, and it’s well worth the visit.

*

OFFICIAL RELAUNCH OF THE CONVERGENCE CONTEST

Which, in turn, brings us back to the contest. Go back and browse through some of the paired examples in that All that is Solid series (Issues 11 through 15) and get yourself into that sort of mindset, and in the dailyness of your own lives, if you should happen to come upon any similar convergent effects, send them in, along with your own sense of what is going on (or at very least a good little accompanying anecdote). Here’s our address:

weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com

We’ll look forward to hearing from you. From time to time, we’ll post our favorites and comment on them as well. We’ll develop the full contest parameters as we go along (how often? should there by prizes? isn’t sublime Wondercab notoriety enough? etc.) But in the meantime, the game is afoot! Hop in!

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

Animal Mitchell website.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

The final tranche of our conversation with Blaise Agüera y Arcas in which all is revealed (ubisuntwise, at any rate); another Convergence Contest winner (already!); and more…

* * *

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com. And do please subscribe and share!