December 9, 2021: Issue #5

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

Welcome once again, and to those of you just joining us, particularly warm greetings to you (with the suggestion that you might want to go back to the introduction to our first issue several months back, here, to get a sense of what we are trying to accomplish with this entire venture). As for this issue: Big occlusions, big consequences, big celebrations, big ideas, big buildings, arguably overlarge protuberances—everything, in other words: monumental!

THIS ISSUE’S MAIN EVENT: From the Archives

A letter to the editor of McSweeney’s, August 2017

ECLIPSE WEDDING RABBI

Fond ones:

I’ve just come home from my fourth lifetime outing as an ad-hoc, highly unorthodox wedding rabbi (previously, I was the “rabbi” at the “wedding” of Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly—actually it was Spiegelman’s fiftieth birthday and when Francoise asked him what he wanted by way of gift, he said that what he was really pining for was a real wedding, since their actual marriage twenty-five years earlier had only been at city hall for anarchistic green card purposes, so she recruited me as the rabbi and R. Crumb headed up the party band! More recently I’d officiated the marriage between two guys in Houston, The Art Guys, and a tree, a nuptials that went tragicomically bad).

Anyway, this time was for the wedding of my dear artist friends, Trevor Oakes (one of the perspective twins) and his longtime on-and-off-and-on-and-off-and-finally-on-again lady love, the ex-architect painter Gerri Davis. Gerri had hit upon the idea to stage the ceremony a few hours from her parents’ place near Asheville, North Carolina, in the lee of the Great Smoky Mountains, in the tiny creekside hamlet of Topton, along the very spine of that recent transcontinental total eclipse, on the day of the eclipse itself. “Come for the eclipse,” went the invite, “and stay for the wedding!”

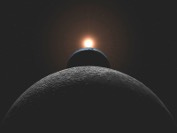

And believe me, the total eclipse itself (between 2:38 pm and 2:40 pm on a blessedly cloudless afternoon) was all that and more: don’t even get me started.

About twenty minutes afterwards, though, with the sun peeking well past the now fast receding moon shadow, a makeshift band of instrumentalist friends (amateur oboist, trumpeter, ukuleleist, keyboard player, and guitarist: the Eclipse Philharmonic, as I’d taken to calling them) launched into a surprise flash moblet rendition of “Here Comes the Sun,” herding the scattered, still awesmacked congregants Pied-Piper-like over two little bridges and onto a leafy breezy little island in the middle of the lazy rapids, where chairs and flowers and candles and a podium had been set up. Once everyone was seated, I led the mother of the bride and Trevor’s father led the groom over the bridges to their respective places (a few moments earlier I’d ducked out back to don my rabbinical gear, beige suit and tie, draped over with a black-stripped white tallis shawl, all capped by a red yarmulke), and then on the far side of the bridges the trumpeter (Gerri’s father) launched into a buoyant New Orleans style solo medley, culminating with “Here Comes the Bride,” his radiant daughter clinging to his side as he now led her over the bridges to the podium, where Trevor and I stood, awaiting her splendid arrival, awesmacked all over again.

The congregants oohed and ahhed and finally grew silent, whereupon I approached the mike to begin my homily. (Do Jews even do homilies? Beats me.) “About four months ago,” I pronounced solemnly, “I got this pesky little splinter on my pointer finger, which thereupon began to bleed on and off continuously, so I called Gerri here in North Carolina asking her to ask her mother about it, because I knew her dear mother was some sort of hand-therapist. I told her that it seemed like I was suffering from a stigmata sent down upon me by a singularly incompetent God, which Gerri repeated to her mother, whereupon in the background I overheard her mother’s confused retort, ‘But Gerri, he’s Jewish isn’t he, and Jews don’t get stigmatas, do they?’ Precisely, I responded. Like I said, we’re dealing here with a singularly incompetent God! Guy doesn’t even know who to smite, let alone where.”

And then, I continued to recount to the congregation how just a few days ago, our mutual friend Bill had asked me what I was doing for the coming weekend, and how I’d told him that I was headed down to North Carolina to serve as the rabbi at Trevor and Gerri’s upcoming wedding, at which point he’d asked, hesitantly, “But neither Gerri nor Trevor are Jewish, are they?” To which I’d told him, and now told the congregation, “No, but then I’m not really a rabbi, either.” Whereupon, reaching into the depths of the podium, I pulled out a full-on sort-of Hassidic-style head-piece (actually a pleated cardboard approximation) and placed it upon my head. For greater authenticity, I hoped, somewhat haplessly.

Anyway, I thereupon launched into the meat of my rabbinical discourse. Because, hadn’t that eclipse been something, or what? Everyone whooped concurrence (always good to get the congregation on your side at the outset, is what I believe and try to practice). And yet, I went on, it’s worth pausing for a moment to ponder the near infinite, indeed precisely astronomical, odds against such an occurrence even transpiring at all. Because for total eclipses to happen, on any planet anywhere, the sun and the moon in question have to occupy precisely the same acreage, as it were, of celestial real estate. Which, in the case of our own planetary system, only happens because the sun is precisely 400 times the size of the moon, and the moon just happens to be precisely 400 times closer to the earth: hence the perfect, veritably lid-like fit. And what are the odds against that sort of alignment? In science fiction films, one regularly sees total eclipses happening on other planets, but not bloody likely that such an uncanny congruence occurs elsewhere, certainly not in our own solar system, likely not anywhere else in our galaxy. And top that near inconceivable coincidence off with the fact that it should occur on the very planet upon which life has evolved intelligent enough to appreciate and marvel at it—what an infinitely further unlikelihood. And not only that, but that such intelligence has coincided with the relatively tiny temporal window that such perfect eclipses have been occurring on that planet—for the moon’s orbit is gradually receding from the earth: several millions of years ago it was too close, and several millions of years hence it will be too far, the required conditions thus pertaining for only a relatively minute fraction of the planet’s entire existence—what are the odds against that!?

Makes you wonder, I pronounced, portentously.

“And yet all of that is as nothing,” I rounded the corner on my extended analogy, “is as nothing,” I repeated, “as all of us here gathered (their endlessly put-upon friends) certainly realize, compared to the odds against these two doofuses, our beloved Sun Lady and Moon Man, ever getting their act together enough to finally marry, for god’s sake!”

And so forth: it was a fun ceremony. Great after-feast, fantastic honky-tonk dancing into the star-dusted night.

But the reason I’m writing you kids about all this is that in the days since, I’ve been thinking, and I no longer think it was all mere coincidence, or at any rate sheer random happenstance, that intelligent life just happened to arise, here and who knows if anywhere else, on what may well be the sole planet anywhere whose moon and sun were thus arrayed, and indeed during the relatively tight interval, geologically speaking, when they were thus arrayed.

Isn’t it perhaps rather the case that it was the occasional occurrence of such total eclipses (granted, very occasional, only a couple hundred times a century, spread all about the globe’s surface, such that, the chances of any individual tribe of protohumans ever seeing one were themselves virtually infinitesimal) that in turn (because, really, the sudden unexpected occurrence of such a celestial event is utterly astonishing, terrifying, unnerving, enthralling, certainly profoundly memorable, and unlike anything else that the primitive creatures would have ever witnessed) might itself have jumpstarted, as it were, an ensuing cascade toward the kind of abstract intelligence we humans all now (granted, to varying degrees) seem to evince and take for granted.

I say “primitive,” but as Jared Diamond and Yuval Noah Harari and their like keep reminding us, it’s a complete misprision to imagine our distant forebears as knuckle-dragging morons of any sort. If anything, they were all, every single one of them, much more intelligent than any of us today (stupefied as we have become by all our labor-saving conveniences)—they had to be (little naked near-defenseless runts that they were) just to get through the day, to evade predators and secure food, shelter, clothing, fire and so forth for the night. And come evening, in a world bereft of other entertainments (or distractions), what must it have been like for them to gaze up at the stars, and (for the yet more intelligent among them) to begin to note the patterns in the waxing and waning of the moon, the way individual stars seemed to rise at slightly different times and in different places along the horizon, the way such patterns aligned with the changing seasons—and then, completely out of nowhere, suddenly one afternoon, to experience the world-upending spectacle of a total eclipse!

It might have been like that early scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey, only minus the intervening aliens and their monoliths (unless aliens were themselves the ones—or maybe God, the One—who somehow managed to pull our moon into its uncannily unique alignment in relation to the sun). Maybe I had 2001 on my mind because one of the congregants at the wedding was our friend Michael Benson, fresh in from Ljubljana—“I couldn’t help myself: suddenly I just watched, spellbound, as my fingers typed in the plane reservation”—who’s just completed the manuscript for his 50th anniversary study of that film and its director Stanley Kubrick and author Arthur C. Clarke, due out in the spring of next year, and we’d dallied a good part of the evening discussing his findings.

Anyway, so, yesterday I mailed a synopsis of all this to another mutual friend, Walter Murch, the legendary film and sound editor and all-around polymath who was the subject of my own most recent book, Waves Passing in the Night, chronicling his improbable excursions into a whole other branch of gravitational astrophysics, and I wasn’t the least bit surprised (nothing about Walter surprises me anymore) to receive, by return email, the following:

Yes, I agree. The beginning of 2001 actually begins with eclipse imagery, long before the monolith is ever introduced.

A journal musing of my own from October 2003:

“If Earth had been cloud-covered, like Venus, would we have developed mathematics to the extent that we did? There is a proof somewhere of how humans could deduce the existence of stars even if they had never seen them. Perhaps we could have done so, potentially, but would our minds be predisposed to think in that direction? Does not the night sky pull our imagination off the surface of the earth and make it dream and speculate: what if? Then add the fact that humanity emerged along with the existence of perfect solar eclipses. The moon is moving away from the earth, so perfect eclipses didn’t exist ten million years ago, and will not exist ten million years from now. Does not the eclipse light the imagination? Did it somehow help to create this wondering animal?

“Given the few humans alive 100,000 years ago, when language (or so we think) began to emerge, and the infrequency of solar eclipses, the ability of an eclipse to kindle the human imagination must be one of those crucial “singularities” in history (like the “eukaryotic singularity”) where the event triggered a paradigm-shift in one individual (or a small group) and then it spread outward from there, carried by language. Solar eclipses are not experienced “globally” by everyone at the same time (the way we experience lunar eclipses)—I have seen only one eclipse in my life (a partial eclipse in London in 1999). The total eclipse that the US has just experienced is the first to transect the continental US in 100 years, more than the average human lifetime. And it was a thin line of totality, only a few miles wide. Imagine the world of 100,000 years ago, and how few people there were back then, and how many would have seen a similar eclipse, unprepared for it by any prediction. And without language how would they have spread the word? Partial eclipses are more common, of course.”

Much to think about…

Much to think about indeed. But what it all got me thinking about is where ideas come from. In this particular case, had I even come to this sudden supposed insight in any sense “on my own,” or wasn’t it perhaps rather the case that a prior set of influences in my immediate past (Kubrick, Clarke, Benson, Murch) had all lined up just so, perfectly, in such a way as to render that momentarily blinding supposition—ha! eclipses, monkeys, the jumpstart toward subsequently cascading intelligence—all but inevitable?

Maybe all thought is just the world itself daydreaming and marveling at itself.

Anyway. Love to all,

Ren Weschler

* * *

AV-ROOM

IN CONVERSATION, ONCE AGAIN, WITH WALTER MURCH

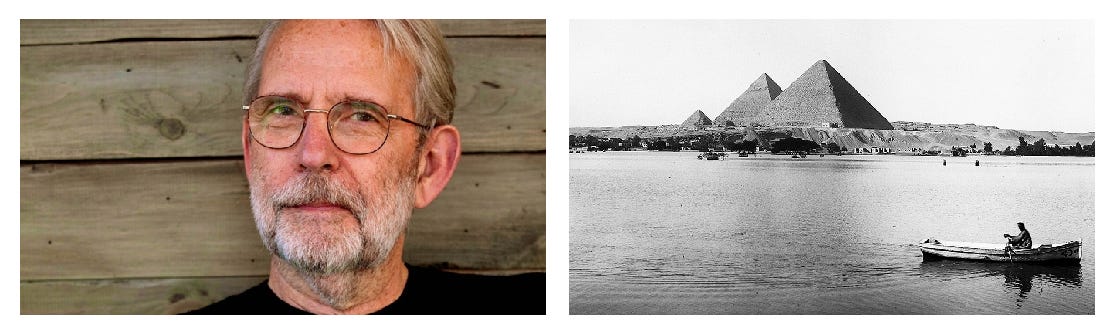

On the Uncanny Mathematics Undergirding the Egyptian Pyramids

As we already saw in Issue #1 of this current Wondercabinet endeavor (and for that matter at the conclusion of the Eclipse Wedding Rabbi entry immediately preceding this one), Walter Murch is a man of many parts. Moving on from his interest in the rampant appearance of golden ratios across faces and screens which he displayed there, this time, as another installment of the series which I curated as part of the Arts Letters and Numbers contribution to the Italian Pavilion of the recently concluded Venice Architectural Biennale, the eminent film and sound editor delves into a wider and more longterm sidebar passion of his: deciphering the uncanny mathematics undergirding the Egyptian pyramids and the possible significance of those astonishingly exacting proportions. It’s not just the way that across an astonishingly brief period (the 120 years from 2624 through 2504 BC) the bronze-age Egyptians managed to fashion over 20 million tons of limestone and granite blocks into five structures taller than any that would be matched anywhere in the world across the ensuing almost 4500 years, indeed right up until the last century and a half—it’s that their engineers and designers did so, or so Murch has come to believe and here endeavors to demonstrate, within a strict dimensional regime blending pi and phi (that selfsame golden ratio) which they then secretly embedded in a mysterious chamber buried deep in the heart of the Great Pyramid at Giza, one that was decidedly not (as has often been assumed) the pharaoh’s burial chamber. But if it wasn’t that, what was it? and why?

Catch my conversation with Polymath Murch here.

* * *

YET ANOTHER FOOTNOTE FROM A BOOK YOU DON’T HAVE TO HAVE READ OR EVER READ(For That Matter Can’t Have Read Because The Book’s Not Coming Out Until This Spring)

THIS TIME OUT, SPEAKING OF ECLIPSES AND MONUMENTS,

YOUR HOST’S NOSE:

FOOTNOTE 22

Not to careen too far off track here, or to be seen too much to be tooting my own horn, as it were, but I will confess that my favorite review ever of my own work began by noting that any master of long-form nonfiction requires “the vision of a novelist and the precise ear of a poet, but just as important is the journalistic nose which can steer him down the proverbial alley,” concluding, “Weschler’s is an unusually fabulous nose.”

Well, as long as we’ve careened this far, I might as well tell you another story. This one is absolutely true, swear to god. Back in high school in the San Fernando Valley in suburban LA, one of my favorite teachers was Miss—(this would have been 1969, so, yes, Miss) well, let’s call her Susie Kay Krefeld, our AP English Lit prof. Bawdy and bodacious, zaftig and curvaceous, after class she would regularly entertain a coterie of her most nerdily-pitched hangers-on, of which I was certainly one, with outré narratives of the wider literary world, alongside tales of her own outlandish sexual exploits (how she’d sequentially bedded every single one of the school’s male PE coaches, as well, over the years, as a good many of the school’s championship senior quarterbacks)—as I say, this was a different time, this was the Sixties: please, Dear Reader, forgive us and forgive her, we nerds certainly weren’t victims here.

Anyway, the last week of that final semester, as I was leaving that day’s class, she pulled me aside and asked me to drop by her office after school, there was something, she said, that she wanted to share with me. The rest of the day was a hormonal wash, my heart doing racing backflips, my mind agog in steamy anticipation.

The moment came, I tentatively knocked on her door, she bade me enter and to close the door behind me. I stood there tongue-tied for a few moments as she seemed to gauge me silently, up and down, with her doey eyes. “Naah,” she pronounced, at length, “we better not.” Mmm-nnn-ggg? I countered, cogently. “No,” she repeated. “It would just ruin our friendship, best to leave things be.” Really? I somehow managed, why? what? Maybe it wouldn’t. “You want me to?” she doubled back, “It wouldn’t ruin things for you?” To which I reverted once again to strangled whimpers.

“Well, okay then,” she resolved, getting up from behind her desk, swayingly sashaying toward me and reaching out for my face.

“It’s your nose,” she declared. Two beats, three. “Really, Lawrence, you have to do something about that nose.”

Continuing: “I should know: I had the same problem. Tell me it’s not the same with you: Out driving, you pull up to a stop sign and a car pulls up alongside you, and you notice how you drag your hand up so as to block all view of that schnoz.” Actually, I couldn’t remember doing any such thing (though I wasn’t out driving all that often, it occurred to me). “You’re subconsciously agonizing about it all the time,” she assured me. “It’s wreaking havoc on your self-confidence.” But was it? I didn’t think it was. “When I was your age,” she continued, “I went and got mine taken care of the minute I could”—it occurred to me that I’d never particularly taken in her nose (maybe that was the whole point) but now that I did, yes, it was perfectly straight, I supposed, tapering down to a fetching button—“and that decision has made all the difference.” (Damn if I didn’t catch the Frost reference, but what good was that doing me?)

Returning to her desk and leaning against its side, crossing her lithe arms athwart her ample and considerably more fetching chest (those breasts that could so easily have been mine, as I couldn’t help but recognize, if only I’d instead been born a pea-brained pug-nosed championship quarterback), Miss Krefeld let out a lilting sigh and, “There,” she assured us both, “that wasn’t so bad, now, was it? And it had to be said.” Going on to dismiss me, “You just think about it.”

And over the years I often have, though not perhaps as she intended: I have no idea how I survived high school.

* * *

FROM THE INDEX SPLENDORUM

Speaking of eclipses and monuments and lolling schnozes, a spanking new entry in the Index! Some of you may recall how our last time out, we speared from out of our vault of miscellaneous wonders a swell little video from about eight years back, in which the Swedish designer Erik Åberg unfurled a whole procession of magically conjoined and tumbling cuboid structures. This time, by contrast, I want to show you a phantasmagoria of images barely eight days old, the latest iteration from an astonishing longterm project-in-the-making by veteran Los Angeles filmmaker David Lebrun, the creator, previously, of such marvels as the legendary 2004 documentary Proteus, a (yes) protean meditation upon the life and legacy of Ernst Haeckel, the seminally influential 19th century artist and naturalist (for a passage from the ecstatic climax of which, see here).

Anyway, for the past dozen years, Lebrun and a team of collaborators have been spanning the globe, amassing tens of thousands of high definition images from museums of archeological artifacts (handaxes, figurines, helmets and so forth) and sites of heightened cultural significance (temples, towers, churches, henges and the like) and conjoining those still images by way of a whole range of dynamic experimental animation techniques.

More on all of that in a moment, but first let’s sample Lebrun’s latest effort, itself a work in progress, though he graciously agreed to let me share it with you in this near final state. The subject in this instance is the Hoysalesvara Temple, from circa 1250 CE, in Karnataka, India. Just watch it and I’ll meet you on the far side.

Gotta love those lolling pachyderms! (In fact they remind me of an essay Oliver Sacks offered me back in 2003 when I was fashioning a prototype of my own stab at a utopian semiannual journal, Omnivore, an initiative that alas proved stillborn at the time but perhaps may be being resurrected to some extent in this current Wondercabinet effort of mine. Anyway see Oliver’s thoughts on early attempts at photo-documenting the elephant’s gait back in the 19th century here.) And that score (!), which Lebrun tells me “pairs a Hindu temple with a Sufi song, with both in their own way constituting paeans of intoxication and delight at the infinite creative unfolding of the universe” — to which all I can add is: I’ll say! By the end Lebrun has the Temple itself positively rocking!

This is merely the latest in a series of dozens and dozens of experimental short films tracing the evolution of all sorts of human forms from all sorts of places around the world as surveyed across varyingly extended tranches of time, all as part of a soaringly ambitious megaproject that Lebrun has taken to calling “Transfigurations: Reanimating the Past.” Perhaps best to let Lebrun himself evoke the project’s wider vision and scheme, which he does in an extended trailer here (especially worth watching because it includes all sorts of samples of other animations). There’s more at the project’s website, here.

The point is that this epic experiment is now rapidly approaching completion, though Lebrun and his colleagues are seeking help in securing final funding and perhaps more importantly promising venues for its full elaboration and display (the show is being offered free of exhibition fees to museums and other educational institutions). Any thoughts or leads any of you might have in those regards—or for that matter general queries or words of encouragement—I’m sure the team would appreciate hearing from you, and can be reached via producer Rosey Guthrie (roseyguthrie@mac.com) or Lebrun himself (davidlebrun@mac.com).

Anyway: Onward, in this instance, finally, to one of my wingman David Stanford’s own takes on the Monumental Sublime.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Enough already with all these guys and their Weighty Monumental Schemes! Next week, Fiat Pash! Which is to say, the confounding lightness of Helen Pashgian—both the director’s cut of my recent NYT piece on this Light and Space pioneer at long last getting her due, and a video of the talk I gave at SITE Santa Fe on the occasion of the opening of her terrific new show there last month. Along with all sorts of other fare positively rife with coolth…