WELCOME

Aye, the sorry state of our roiling planet, and yet, withal, the late Polish master Adam Zagajewski would have had us “Try to Praise the Mutilated World,” —and in that spirit a video out of the Ukraine that went viral earlier this week (perhaps following on from my brush with Bikont at the end of our last Wondercabinet) had me wending back through my COMMONPLACE BOOKS in search of some earlier Polish takes on repression and resistance, where I found pertinent passages by Ryszard Kapuscinski and Stanislaw Baranczak from just before the days of Solidarity. So we will start there. Then, for the issue’s MAIN EVENT: “All that is Solid,” the first installment of a five-part extended essay anatomizing the phenomenon of convergences as a means of delving toward a unified field theory of cultural transmission (don’t worry, you’ll see). Wrapping things up, in the INDEX SPLENDORUM: extended moments, in turn, of uncanny stillness and antic exuberance.

* * *

The current moment

FURTHER LEAVES FROM MY COMMONPLACE BOOK

Of all the video coming out of the Ukraine these last grim days, perhaps the most impressive, for me—and arguably the most portentous for Putin and his cohort in the Kremlin—is that one of the curbside exchange between a stout Ukrainian matron and a hapless (even if formidably armored) Russian soldier:

So much to unpack there, but especially that business of offering the soldier a handful of sunflower seeds—sunflowers being the national flower of Ukraine. I was of course put in mind of those days when the anti-Vietnam War protesters used to slip flowers into the barrels of the National Guardsmen’s fiercely extended rifles, but the register in this more recent instance was so much more charged and freighted.

The barely concealed subtext: “Here, son, take this offering, put these sunflower seeds into your pocket. That way, after you fall in battle one of these days, as you surely may well, the great flower stalk will burst from the grave and help your shattered mother to find you.” It is as if with the offer, she herself is assiduously planting the subversive thought in the conscript’s mind.

That viral video reminded me as well of two extraordinary passages from Polish literature of oppression and resistance from over forty years ago (in that sense, the wheel of history may yet, pray, be coming back round full circle): The one from Ryszard Kapuscinski’s allegorically-shaded evocation of the 1979 revolution in Iran in his book The Shah of Shahs; and the other (somewhat less well known), Stanislaw Baranczak’s uncannily prescient poem, “Those Men, So Powerful,” from 1978, a mere two years before the upsurge of Solidarity.

Both of which may well be coming to speak to the situation of, and the specter haunting, Putin and his cohort back in Moscow.

Now the most important moment, the moment that will determine the fate of the country, the Shah, and the revolution, is the moment when one policeman walks from his post toward one man on the edge of the crowd, raises his voice, and orders the man to go home. The policeman and the man on the edge of the crowd are ordinary, anonymous people, but their meeting has historic significance. They are both adults, they have both lived through certain events, they have both had their individual experiences. The policeman's experience: If I shout at someone and raise my truncheon, he will first go numb with terror and then take to his heels. The experience of the man at the edge of the crowd: At the sight of an approaching policeman I am seized by fear and start running. On the basis of these experiences we can elaborate a scenario: The policeman shouts, the man runs, others take flight, the square empties. But this time everything turns out differently. The policeman shouts, but the man doesn't run. He just stands there, looking at the policeman. It's a cautious look, still tinged with fear, but at the same time tough and insolent. So that's the way it is! The man on the edge of the crowd is looking insolently at uniformed authority. He doesn't budge. He glances around and sees the same look on other faces. Like his, their faces are watchful, still a bit fearful, but already firm and unrelenting. Nobody runs though the policeman has gone on shouting; at last he stops. There is a moment of silence. We don't know whether the policeman and the man on the edge of the crowd already realize what has happened. The man has stopped being afraid — and this is precisely the beginning of the revolution. Here it starts. Until now, whenever these two men approached each other, a third figure instantly intervened between them. That third figure was fear. Fear was the policeman's ally and the man in the crowd's foe. Fear interposed its rules and decided everything. Now the two men find themselves alone, facing each other, and fear has disappeared into thin air. Until now their relationship was charged with emotion, a mixture of aggression, scorn, rage, terror. But now that fear has retreated, this perverse, hateful union has suddenly broken up; something has been extinguished. The two men have now grown mutually indifferent, useless to each other; they can go their own ways. Accordingly, the policeman turns around and begins to walk heavily back toward his post, while the man on the edge of the crowd stands there looking at his vanishing enemy.

[From The Shah of Shahs, Harcourt Brace, 1982, p.109. Trans. William Brand & Katarzyna Mroczkowska-Brand.]

Those men, so powerful, always shown

somewhat from below by crouching cameramen, who lift

a heavy foot to crush me, no, to climb

the steps of the plane, who raise a hand

to strike me, no, to greet the crowds

obediently waving little flags, men who sign

my death warrant, no, just a trade

agreement which is promptly dried by a servile blotter.those men so brave, with such upraised foreheads

standing in an open car, who

so courageously visit the battle-line of harvest operations,

step into a furrow as though entering a trench,

those men with hard hands capable of banging

the rostrum and slapping the backs

of people bowed in obeisance who have just this moment been pinned

to their best suits with a medal,always

you were so afraid of them,

you were so small

compared to them, who always stood above

you, on steps, rostrums, platforms,

and yet it is enough for just one instant to stop

being afraid, or let’s say

begin being a little less afraid,

to become convinced that they are the ones,

that they are the ones who are the most afraid

[From The Weight of the Body: Selected Poems, Triquarterly Books/Northwestern University/Another Chicago Press,1989, p. 23. Trans. Magnus Krynski & Robert Maguire.]

So there’s those two, but there’s also the joke that used to make the rounds in pre-1989 Romania, the dictator Ceausescu’s grimly frozen totalitarian domain—how an ordinary car was stopped at a Bucharest stop light when suddenly a speeding stretch limo came smashing into it from behind, accordioning the little car’s rear, and that’s it, the guy in that first car has had it: he reaches into his backseat, grabs a crowbar, exits his crumpled vehicle and proceeds back to the limo, whose front hood he takes to bashing, over and over again. At that precise moment, a truck pulls up behind the limo, eases to a stop, and the truckdriver hops out of his cab, even bigger crowbar in hand, and takes to smashing the limo’s back hood. The uniformed limo driver emerges and walks back to confront the truckdriver: “That guy up front, I understand why he’s attacking this car, but what about you, what the hell’s your beef?” To which the trucker replies, “You mean it hasn’t started?”

Everybody, of course, realizing what “it” would and must mean.

May it soon arrive in Russia!

* * *

And now, on to this issue’s Main Event:

All That is Solid:

Toward a Taxonomy of Convergences & A Unified Field Theory of Cultural Transmission

PART 1

To begin with, perhaps, a story. After I graduated from college, across which I’d tended to change majors every semester—literature, religion, political theory, cultural history, psychology, classics, philosophy—studying, as my grandmother parsed matters, fretfully, at the time, “Nothing that will bring him any good,” a family friend, a psychologist, pulled me aside at some celebratory function or other and offered to have me come by his office sometime, so as to help me figure out, as he put it, “What you should do with your life.” So, anyway, I went over to his office a few days later and he proceeded to subject me to a battery of tests. You know, for instance that 800-question binary personality inventory: Would you rather be a stone or a vegetable? A firefighter or an arsonist? Do you prefer strawberry or chocolate? Blondes or brunettes? That sort of thing. And then of course, somewhere in there, there was that old standby, a Rorschach test: all those lurid inkblots. At length, we wrapped everything up, and he asked me to give him a few weeks to score all the various diagnostic tests, and to come back to see him thereafter.

Which I did. He pulled out my file and riffled through the pages intently. It turns out, as he explained, that they score those Rorschach tests on all sorts of indices: aggression, sexuality, suggestibility, whatever—and that one of them is general free-associative tendencies. “And on that one,” he now informed me, pausing, “—you have to understand I’ve been administering these tests for over thirty years now, and for that matter I’ve called around to ask some of my colleagues, and none of us has ever seen a score like yours. You are completely off the charts. And that,” he suddenly turned very somber, “is not necessarily a good thing. You are going to have a terrible time finding any kind of life focus.”

And nor do I necessarily deny that. For as long as I can remember, my mind has tended to wander promiscuously, from one thing to often quite an odd other (if I stop to think about it, I can usually trace the line of associations, but it’s gotten so I no longer even bother). “Uh oh,” my daughter is given to saying, “Daddy is having another of his loose-synapsed moments.”

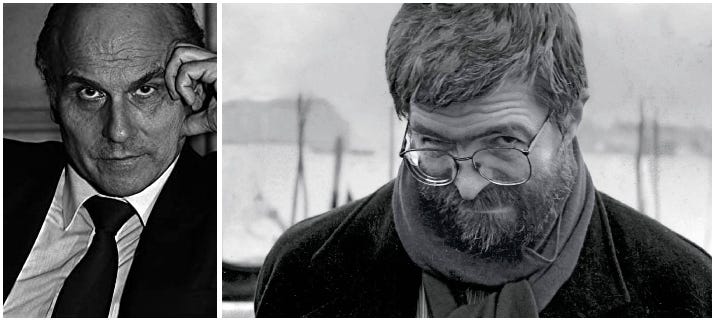

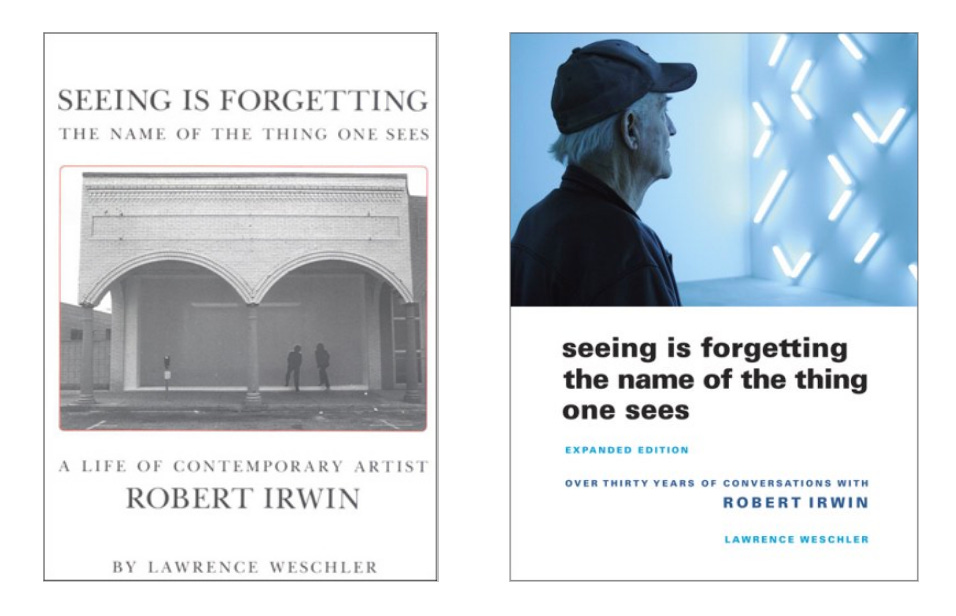

Not that I necessarily went gently into that great night. Indeed, as I look back on things now from the vantage of several decades, what was to become my first book-length project, my biography of artist Robert Irwin, was, as its title (Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees) implies, a desperate attempt to curb that rampantly loose-synapsed predisposition, since for Bob Irwin, the whole point was to stop free-associating to anything, to learn to still the inner jabber (something he’d spent literally decades systematically training himself to be able to do) such that one might simply tend to the thing in front of one, the thing itself, perception pure and simple. For the longest time our relationship used to consist of my launching out, “You know what that reminds me of…” and his snapping, “Shut the fuck up! I don’t care what it reminds you of. Can’t you just look at it, experience it?”

And as I say, I tried. I wrote a whole book trying, and twenty-five years later a whole massively expanded second edition of that book, but pretty much for naught, “Shut the fuck up” still being one of Bob’s principal terms of endearment whenever we get together. Again, I don’t blame him. It’s just not in me, however, to keep from free-associating like that.

Eventually, in 2006, I succumbed full out to that tendency, publishing Everything that Rises: A Book of Convergences, based in turn on a series of pieces I’d been publishing in McSweeney’s across its first couple dozen issues. A “convergence,” as I came to characterize the term, started with a sort of conceptual rhyme, two things (a photograph and a painting, say, or a poem and a photo, two magazine covers, whatever) that looked improbably alike; though as I say, that was just the rhyme, and a full scale convergence consisted, as it were, in the poem filigreed around that rhyme: an essay occasioned by the initial pairing but then taking matters further, worrying out some of the match’s possible implications.

Thus, for example, I might take these two images:

That’s Jackson Pollock 1952 on the left, and Time Life Books 1954 on the right, “galaxies in collision.” And the point was that not only do they look alike, but the galactic, the nebulous, the empyreal, was the way critics often characterized those Pollock drip paintings at the time. An association Pollock himself seemed to invite, with those ostentatious photoshoots of him, godlike, casting veritable skeins of paint onto the vast empty canvas spread below him. They’re so silent, being another of the common critical responses—to which one might have been tempted to counter-respond, “Duh, yeah, they’re paintings, of course they’re silent.” Though on second thought, you could see what the critics were getting at: the imagery was incredibly explosive, cosmically vast and roiling, and yet it seemed to partake, precisely, of the vacuum-like silence of outer space.

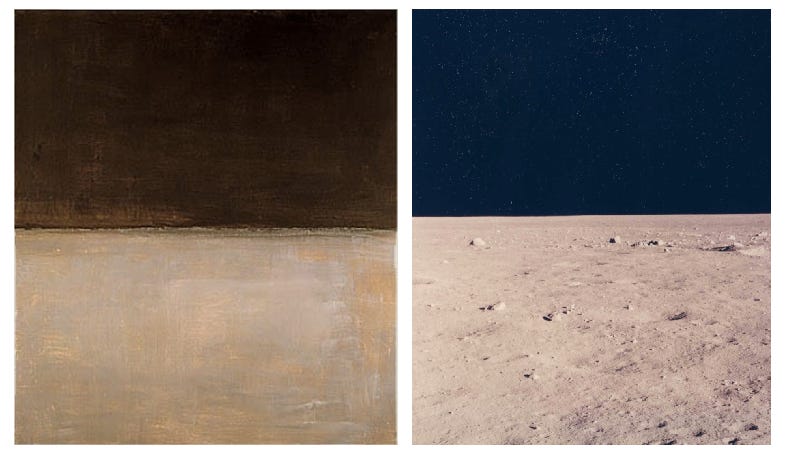

Anyway, then I’d move on to the progressive sequence of Rothko’s mature paintings, how they famously began with those dazzlingly colorful cloudforms of color, one stacked atop the next (talk about totemically mute!),

which in turn gradually darkened with the years, culminating finally, in 1969, just before the artist’s suicide, with those black on luminous gray razor slice vantages, regarding which everybody is accustomed to saying, “Well, yeah, you can see he’s about to commit suicide, everything’s so desperately bleak.”

A sentiment with which I used to concur, though one day, looking once more at that date, 1969, I suddenly thought, “Hmmm, wait a second, what was on TV that summer?” Because, of course, that was the summer of the Apollo moonlanding, which is what Rothko would have been seeing.

Now, I want to be clear: I am not saying that Rothko just copied his final imagery off his TV set, the important thing with all of these convergences is not to become reductionistic—the history of imagery is always marvelously overdetermined, that’s one of the things that makes it so endlessly fascinating to explore—I just do find myself wondering what it must have been like for Rothko, gazing at the TV that for him terrible last summer, to witness what was after all this tremendous human achievement, a human footprint on the moon!, and yet, after all of that effort, what had we found there? Nothing. A yawning void. A desperate emptiness. Or so might those final paintings lead us to believe.

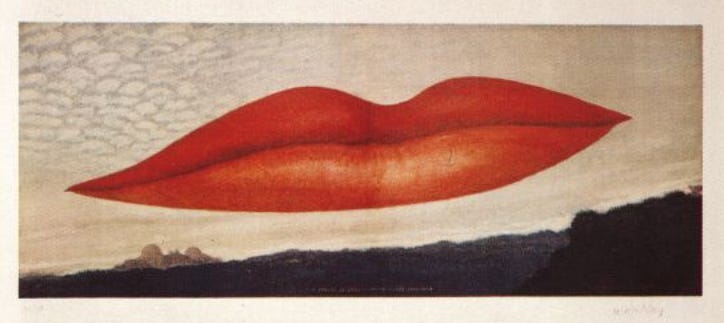

Or, to take another example, an obverse landscape, as it were, lush and life-drenched. One day a friend of mine was showing me a book of Sigfrido Geyer’s photographs of mountainous tropical Venezuela when he turned to one particular two-page spread and I immediately gasped, “The Rokeby Venus,” for of course it looked just like (I can hear Irwin in my head, “Shut the fuck up!”) Velasquez’s magnificent nude of 1650; though on second thought, noticing the tracelike goatpath slicing horizontally clear across the mountain face in the photo, on second thought, I said, “No, wait, it’s the Man Ray lips!” in turn recalling the voluptuously desolate canvas Man Ray perpetrated in 1933, featuring the gorgeous lips of his only just recently departed mistress-muse Lee Miller spread across the evening sky.

“The Hour of the Observatory,” Man Ray had titled that painting, and there you can see it in the painting’s lower left hand corner: the observatory outside Paris which the French had insisted on claiming was the site through which ran their zero-degree longitude (this long after the rest of the world had settled, at an international conference in Washington DC in 1884, on Greenwich as the site for everyone else’s zero degree, indeed right up through 1914)—hence the significance of Man Ray’s otherwise enigmatic title, he himself having arrived, he felt, at the zero-degree moment of his life. But wait a further second, I now went on to surmise, because surely Man Ray’s lips must have been based on Velasquez’s Rokeby nude (look for instance at the way black satin sheet beneath Venus reads as a lower lip, look at the way her right elbow extending beyond the couch is echoed in the upper right lip of the Man Ray).

At which point I have to admit I began to have shut-the-fuck-up doubts myself, surely I was taking things too far. Except that a few days later, consulting a biography of Man Ray, I came upon this photograph that Man Ray himself took a few years after that, his painting hanging on the wall above his bed, and on top of the bed…well see for yourself

And then, a few weeks after that, I came upon another painting, in a book about Chagall. Now, The Hour of the Observatory was painted in Paris in 1933; and in that same Paris in that same 1933, Chagall painted his Nu au dessus de Vitebsk. (Look at the cathedral dome in the place of Man Ray’s observatory!)

So, go figure.

Maybe one more example. That’s Magritte, Time Transfixed (La Durée Poignardée), 1938, on the left. And on the right, that’s a truly memorable accident at the Gare Montparnasse, in 1895, three years as it happens before Magritte’s birth. (The train engineer’s clocks, one surmises, were most likely on Greenwich time.) I don’t know, but it seems to me that Magritte must have had that overrunning train image lodged somewhere in the back of his mind. But as it happens, that’s not what truly captivates me about this pairing. Rather it’s Magritte’s title: Time Transfixed.

For, before that Washington DC conference in 1884, time had been true: in every village noon had occurred at the precise moment the sun reached its solstice zenith over the village spire; which in turn meant that clocks in towns a few dozen miles apart might be several minutes apart; which in turn didn’t matter till the invention of transcontinental train travel, when a train stopping at seventeen places between New York and Chicago, say, might need to carry seventeen different timepieces on board, just to stay on schedule. Hence the need for time zones, which came into being alongside Greenwich Mean Time at that Washington conference (the vote having been 42 for, with France alone against). The thing I just end up pondering, or that Magritte nudges me into pondering, is whether it’s any wonder that a genius, born in 1879 and growing up in a world grappling with issues of simultaneity and the like (“But when it is noon in Paris, what time is it in Ulm?”) might go on a few dozen years later to formulate an entire Theory of Relativity in which trains themselves, and “lightning striking our rail embankment at two places A and B far distant from each other” would prove the principal props in his thought experiments. Just wondering is all.

So. You get the idea. As I say, I put together a brace of these and in 2006 we published that book, Everything that Rises, and in celebration of the book’s release, the good folk at McSweeney’s launched a sort of contest over their website, inviting readers to submit their own convergences, upon the winners of which I would then be called upon to comment. And from the very start, it was pretty terrific the stuff that came pouring in over the transom.

For example, there was this one, submitted by one Daniel Erker (remember, we were in 2006). And yes, that’s Goya’s Saturn Eating his Children to the left, and President Bush doing I’m not quite sure what there, to the right. The crazy thing was that in ensuing weeks, others began chiming in with disconcertingly similar sorts of vantage: there seemed to be a veritable epidemic of this kind of hankering for baby brains among the high and mighty.

Or here’s another one, submitted by artist Lauren Redniss. That’s veiled Palestinian women at an amusement park on the West Bank during the 1990s, being whirled about by a spaghetti-strapped Siren of Liberty; and not to have been outdone, hooded families from Klan No. 21 in Canon City, Colorado, on a merry outing to the local Ferris wheel, sometime during the Klan surge of the 1920s. One doesn’t know quite what to say.

The legendary film editor Walter Murch submitted one of the most extraordinary entries, a single-shot convergence, which portrays the clear-cutting of a Swedish forest as seen from the air, the loggers, presumably hesitant to be seen from either of the two parallel roads to the top and bottom of the scene, burrowing in on a narrow truckpath and then branching out like mad.

There was a remarkable upwelling of Christological resonance in submissions to the contest, some of it occurring in the most unlikely places, as in Clint Roenisch’s submission of Rene Johnston’s press photo of swimmer Samantha Whiteside being hauled to land following her 2006 52-kilometer swim of Lake Ontario, set alongside El Greco’s 1587 Pieta (at least Jesus didn’t have to deal with the paparazzi, unless one considers the Old Masters themselves to have been the paparazzi of the Passion: flash, flash, flash).

Similarly, there was Charlie Hopper’s submission of a typical 1950s snapshot of his own World War II veteran father’s raising of the backyard clothesline, which as in no doubt several similar such instances, subsequently brought to mind Joe Rosenthal’s historic photo depicting the raising of the flag over Iwo Jima. The interesting thing about the latter photo, though, is why, of all the thousands of photos taken throughout the war-wracked world on February 23rd, 1945, that was the one that editors throughout America, all of them acting independently of each other, all chose to put on their front pages the next morning.

And I would argue—briefly here but at greater length in the pages that follow—that while the compositional perfection of the image (that sublime diagonal), the determined strength of the depicted soldiers, and so forth, may all have played a part, the main reason is that this is an image that Rosenthal first and all the editors later all knew by heart already, for they’d seen versions of it a hundred times before in the myriad images of Christ raised on the cross, as for instance in the 1610 Rubens reproduced here.

Furthermore, that barely conscious echo helped retrospectively to cast, if only subliminally, the entire miserable war effort in the Pacific in a fresh and affirming light, the island hopping campaign becoming a sort of Stations of the Cross, with Mt Subayachi recast as Calvary mount, and the flag raising a sort of Crucifixion pointing toward a Resurrection and the Life.

*

And then there were the ones that just came barreling out of left field, such as Benjamin Morris’s rigorously argued contention that with Dining Room Scene #2 from his 2003 Krefeld Series, American artist Eric Fischl just had to have been channeling Paolo Uccello’s St George and the Dragon. And indeed, how could he not have been?

Note the crazy spiral swirl of a rhyme in the right-hand corner (Bruce Nauman’s “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths,” indeed!), or the parkay floors, or that obscene dragon of a male chauvinist husband to the left (with his rampant Evian prick and those shadow wings extended), his crumpled victim wife as if astride her galloping chair steed, Gerhard Richter’s society dame descending the stairs in the painting to the left echoing the captive princess in the Uccello.

Surely something is going on here. But precisely what?

That is the question I propose to pursue across the next several issues of our Wondercabinet fortnightly. What exactly is going on when we encounter such rhymes? As you may well imagine, there is a whole array of possible answers, and I will be endeavoring to lay out a typology, as it were, a taxonomy, of the convergent. And then, who knows, in a few weeks maybe in addition we’ll start up that Convergences Contest all over again.

* * *

PREVIEW OF COMING ATTRACTIONS

(All-that-is-Solidwise)

***

(Talk about convergences)

INDEX SPLENDORUM

Two extremes from across the wide spectrum of primate possibilities

1)

For more on Miyoko Shida’s rendition of Mädir Rigolo’s Sanddorn Balance, see here.

2)

For more on Zola, the 14-year-old 380-lb silverback gorilla at the Dallas Zoo, see here.

***

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

We will move on into All that is Solid’s taxonomy of convergences (starting out from Apophenia, proceeding on past Accident, and through Affinities); and we’ll delve as well into warpages of time and space, for starters in mid-nineteenth century still photography, and then in the astonishing recent cutting-age investigations of the New Zealand-born, Melbourne-based art videographer Daniel Crooks.

Ah, this is fabulous. And an infectious way of looking, I think: I know that after I read EVERYTHING THAT RISES... I started seeing these things everywhere: https://austinkleon.com/2018/09/21/the-world-keeps-showing-me-these-pictures/

My favorite: Hilma af Klint vs. WEB Dubois: https://austinkleon.com/2019/04/06/af-klint-vs-du-bois/