WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Summertime, and the trilling is easy. Or so we hope you will agree. This time out, something a little different, one sole main event in the form of a cascading sequence of developmental instances and commentaries. You’ll see. Kick back and let the good times flow.

* * *

The Sole Event

A Trill of Entries on Theory of Mind

A passage from the last section of my conversation with Blaise Agüera y Arcas, back in Issue #19 of this Wondercabinet series, in some ways the nub of our entire conversation, has kept thrumming back to mind in recent weeks. To wit:

BAA: Well, I agree with you that theory of mind and consciousness are very closely connected.

LW: Describe for the people in the peanut galleries what “theory of mind” is.

BAA: So theory of mind is the way that I, Blaise, conceptualize what is going on in your, Ren’s, head. So that my theory of your mind is that something is going on in there.

LW: That somebody is home?

BAA: That's right, that somebody is home. And, obviously, it's very, very valuable for us to have one of those things, right?, because if you're in the monkey troop and you see another monkey coming toward you, it would behoove you to be able to understand that monkey’s psychology: What are they paying attention to? What are they thinking about? What do they know? What might they do next? So it's highly adaptive in any kind of social environment to have a theory of mind. And, by the way, this is a theory of consciousness that I subscribe to, as expounded by Michael Graziano, he's also at Princeton, in the psych department.

LW: He’s the author of Consciousness and the Social Brain, right?

BAA: Yeah, I think that’s a very good book. And his big idea is that consciousness is first and foremost social. If you have this faculty of forming a model of somebody else's mind, for reasons that make complete sense, then, of course, you'll form a model of your own mind, too.

LW: And there, you're very much in Sartreland. Jean-Paul Sartre who says (reading): “We live our lives as if we are telling ourselves a story. And we live surrounded by the stories of others.”

BAA: Exactly. And the story that we tell ourselves is self-consciousness. In my opinion.

LW: And we wouldn't even have occasion to think of it if we weren't surrounded by others who we infer also have consciousness. That’s why I come into existence, as Sartre puts it, by way of the Gaze of the Other. If I lived completely by myself on Mars…

BAA: …then, yes, it's not obvious that you would develop self-consciousness. That's right. And in fact, there is some animal evidence for that, by the way. There are only a very small handful of animals who can pass the Dot Test, where if you put a dot on their forehead and you show them their image in a mirror, they realize that that dot's on their forehead, right?

LW: An elephant can do that, I believe.

BAA: An elephant with a lot of work can do that, yes, though only some elephants and only with a lot of time and work

Many monkeys on the other hand do that quite readily. However, if you raise a chimpanzee in isolation, they can't do it.

LW: And that's similar to the situation of wolf children, the Wild Child raised without human contact in the wild: if they are not reintegrated into society before puberty, they will never be able to learn language. They'll learn pointing verbiage, the names for things, but they will never be able to learn syntax, how to create sentences. Puberty is very interesting in that regard. Oliver Sacks likewise tells the story of a guy who lost his vision very, very early, I think almost immediately, but had been living a perfectly integrated life as a blind masseur, but the moment they give him vision as an adult, everything goes haywire, to terrifying and irredeemable effect, because there are just things you can’t learn, in this case visual syntax, as it were, after puberty—and he eventually asks to be rendered blind once again... (Sacks, “To See and Not to See,” in his An Anthropologist on Mars collection).

BAA: This is because of the plastic period of childhood, plasticity declines with age. There are similar stories, I'm sure you've heard them, about cochlear implants for deaf teenagers. If you try to give it to them late, then it almost never works: it just registers as noise and it’s horrible. Yeah, there are certain plastic periods during which you either develop that circuitry or you don’t…and indeed, the sense of self, or attaining theory of mind or social consciousness, I think is probably similar. I'm sure there's also a plastic period.

LW: So, anyway, my hankering doubt or my ongoing misgiving, which feels very human and very non-machinelike, and the thing that I keep on saying is, how, No, Nahh: just because, even in the fictional context of your recent novella Ubi Sunt, the character that I took to be your stand-in and therefore a real person, there at the end, turns out maybe to have been a supremely sophisticated bot after all, that doesn’t mean that I can infer that it has consciousness the way that you or I have consciousness, or anyway the way that I assume you do.

And furthermore, I'm going to be damned if I ever will believe that.

{Or as I phrased this same point elsewhere in our conversation: Just because some bot or digital network evinces consciousness doesn’t mean that it experiences consciousness, and there’s a world of difference between the two.}

BAA: I on the other hand believe that that the process of understanding that there's somebody home is a kind of a dance or an interaction in which it becomes clear that I have empathy for you and that you have empathy for me, that we exist as people for each other. In time, I don’t see why that couldn’t happen between a person and a bot—and in that interpersonal sense, which I think is the only one we can really say anything about, a bot could indeed achieve personhood, with much if not all that that implies.

As it happens, long before this conversation, I’d been keeping a digital folder on my laptop entitled “Theory of Mind,” into which over the years I’d occasionally file articles, video links, and private jottings around the theme. I don’t claim any particular expertise (I never even took any courses in “Child Development” or “Language Acquisition” or the like back in college)—just an abiding curiosity and, more to the point, sense of marvel.

But after that conversation with Blaise, I thought it might be fun to crack open the folder and share some of its contents with you fellow Cabineteers. You may have already come upon some of these yourselves over the years (I claim no special purchase on the finds in question), and some of this may just be obvious to the more professionally schooled among you (I have no doubt that there are all sorts of technical terms to describe some of the things we’ll be witnessing.). But what the hell, we’re in the dog days of summer, and what better season for a conceptual walkabout?

I’ve rearranged the entries in a sort of developmental order for the purposes of this Cabinet, beginning in the Archive with a talk piece of my own, from shortly after the birth of our daughter Sara—and we’ll go on from there…

* * *

From the Archive

Sara's Eyes

New Yorker talk piece

March 9, 1987

Thirty minutes after her birth, my daughter was already taking my measure. She lay in my lap, startlingly alert, scanning me as I scanned her, our gazes moving about each other's bodies, limbs, faces, eyes—repeatedly returning to the eyes, returning and then locking. The same thing happened, I soon noticed, as she lay cradled in my wife's embrace, this locking of gaze into gaze. And it was only gradually that the wondrous mystery of that exchange began to impress me—for not even an hour earlier my daughter's eyes had been sheathed in undifferentiated obscurity, and now what seemed most to capture their attention? Other sets of eyes. (Not noses, mouths, lights—eyes!) How could this be? Of all the possible objects of regard, what is so naturally compelling about two dark pools of returned attention? I could already imagine the scientific explanations—that the newborn infant displays a quantifiably verifiable predilection for certain facelike configurations, for example, or that this predisposition to gazing at eyes is instinctive, a sort of visual sucking reflect—but all such explanations seemed to beg the question. For I already knew that she had a predilection for facelike configurations, for dark dots ranged in pairs—the evidence was as obvious as the face before me—and the explanation for this predilection was equally obvious: because "facelike configurations" are like faces.

A few hours later, as I was trying out some of these notions on a friend of mine, he concocted an instant hypothesis in the sociobiology mode: "The ones who gazed up at their parents' noses simply got tossed out of the cave." I kind of liked that explanation. At least, it tapped into the primordial horizon that gazing into my newborn daughter's gaze summoned forth in me. My eyes locked on hers, I'd had a sense that I was gazing into origins, the ur-past—that this gaze of hers was welling up at me from deep beyond the past's past. Of course, that sense of things was all wrong, for, eye to eye, it was she who was gazing into the past. I was gazing into the future's future.

*

A pair of primate instances

Baby chimp’s first laugh

There are so many things I love about that one. Beginning with the infant chimp’s sheer capacity for joy, from very early on, and again the locked-in gaze of her response, laughter itself being social from the start, and how the experience either summons up an innate craving for more or itself instigates such a desire. And the sheer intellectual acquisitiveness—nay, voraciousness—from early on: this sense of the way, as has often been noted, that we are all, all of us, even the monkeys among us, virtual Einsteins across the first several years of our existence (all of this happening within a brain that didn’t even exist just a few months earlier) after which it all gradually falls away (except, perhaps, for the actual Einsteins among us!). The way, so evident in the middle passage of this video, that that acquisitiveness and curiosity is intimately tied to the hands (and, in chimps, feet, as well), to the way they grasp and manipulate the objects in their surround (both physical and conceptual), so much so that it’s absurd to make any distinction between the brain and the hands, they are all one system (see the philosophical work of both Colin McGinn and Alva Noe in this regard). And finally, with that (first?) visit to the primate enclosure, the nascent sense of recognition, of fellow feeling, and the way it in turn gets summoned and buttressed by the evident interest of the other monkeys in this new fellow apparition. One wonders, does the infant immediately recognize a difference between its up-till-now (human) caregivers and the fellow creatures in the enclosure beyond? (And if not, when does that kick in?)

Now, as any parent knows, the craving, the insistent demand for such soothing attention can at times become downright tyrannical. It’s fun to see how the demand can cross species lines, as in this next video:

Coatimundi affection-hog

*

Artemis learning to talk, and Ren learning to talk Artemis

Some of you may recall my goddaughter Artemis, who made her first appearance in the Cabinet back in Issue #4 (“I had an idea.” “What was it?” “It was great!”). She’s the daughter of my artist friends Trevor and Gerri, whose solar eclipse nuptials I presided over in my sometime role as sorta rabbi several years back (see Issue #5 ). Well, I like to check in on Artemis as often as possible, and as it happens, Gerri happened to be videotaping an early such interaction between the two of us in a noisy restaurant when something completely remarkable happened right before our eyes. Let’s see, this would have been on July 21, 2019, so Artemis would have been around ten weeks old (birthday: May 9, 2019), and she’d already been vocalizing and gurgling for some time, but seemingly without any willful control, sounds just pouring out.

This time (and you can view our conversation here), she and I were rapt in each other’s presence, gurgling away at each other, when she clearly began to try to will appropriate responses to my provocations. It was a full-body, full-concentration effort (those eyes, that gaze!), as if she were veritably trying to squeeze the appropriate sounds out of her larynx (something that had her legs and arms grasping for purchase, her face contorting with the effort: see time signature 1:18 ), and then, suddenly, at 1:47, the desired sound seemed to pop out, to her immediate satisfaction, and mine as well. The floodgates seemed to open (2:02). And completely unthinkingly, as if by way of a primordial sucking reflex of my own, I responded by aping her sounds, and she in turn vocalized her satisfaction at that, and presently we were merrily prattling away at each other: she was teaching me to talk.

Which in turn reminds me of an astonishing piece of happenstance video that was circulating around the net a few years back, a pair of identical twins (one very slightly more advanced than the other) engaged in a spirited babble-conversation (this would presumably have been a good many months, in developmental terms, after my interaction with Artemis) by the side of the kitchen fridge. Lucky parent to have been there to witness it, (and generous co-marveller to have shared it).

Identical twins talking

*

My own story of the precocious little girl at the party who had I and You backwards

How I wish I had a video of this one, but alas, you are just going to have to take my word for it. Decades back (this would have been before the birth of our own daughter), my wife and I were at a party of some friends and among the guests was a charming young toddler, maybe two years old or so, who was astonishingly precocious verbally. A veritable chatterbox, she had strong opinions on everything, which she delivered in a startingly expansive vocabulary. There was just one thing: she had “I” and “you” backwards.

This phase may well be something that all kids go through, and it’s certainly understandable: I mean, she called herself what other people called her (“you”) and called them what they called themselves (“I”). Indeed, it’s something of a wonder that toddlers ever climb their way out of that paradigmatic paradox: there’s certainly no behavioralist model to account for how they do it. Indeed, the intellectual leap involved feels almost originary: the primordial spark, the very seedbed of intersubjectivity. (Talk about Theory of Mind!) We just don’t ordinarily have occasion to fully witness the transition because it seems to happen before most kids have acquired full verbal range. Except in this case.

The girl sat on my lap as I read a book to her, until at one point she suddenly declared, common-sensically, “You have to go to the bathroom, I have to take you!” Actually no, I countered, I really didn’t. “No!” she insisted. “You do! And I want to take you. Right now!” Oh! I suddenly grokked the situation, and took her. Later, she went around asking people their names and then breaking into “Happy Birthday” serenades on their behalf, songs in which she was managing to squeeze in three celebrations of herself (“Happy birthday to YOU!”) for every one she had to begrudge her interlocutor.

Within days she’d doubtless accomplish the flip. But how, one wonders, just how?

*

The lingering porosity of the border between self and world

Even after “you” and “I” have been straightened out, the border between the self and the world nonetheless remains remarkably porous through the first several years of infancy and toddlerhood (sort of a conceptual correlative to the way it still takes a while for the bones of the skull to solidify following the birth that allowed the neonate through the Fallopian passage in the first place). Which brings us back to Herz Frank’s “Ten Minutes Older” short, which has already made two appearances in the Cabinet, the first on its own terms, the second as the occasion (last time out) for Alejandro Iñárritu’s Convergence Contest Win. There is suggestible empathy, to be sure, and then there’s however-you-want-to-describe what’s going on across these ten minutes.

Herz Frank: “Ten Minutes Older”

(Latvian kids watching a puppet show)

{SURPRISE NEW CONVERGENCE CONTEST WINNER!}

Actually, I suspect several of the cinephiles among you may have experienced this convergence the last time we posted that Herz Frank short, but only Michael Benson had the presence of mind to mail his catch in, for indeed, it takes nothing away from Frank’s 1978 achievement to acknowledge that he himself must have been influenced by that other master of the French New Wave, Francois Truffaut, in his first cinematic outing, with Les Quatre Cent Coups of 1959.

Truffaut’s Les Quatre Cent Coups

And there too we see the porosity between self and world which only gradually solidifies as we get older and, come to think of it, melts right back into its originary state every time that as adults we enter a movie theater. Once upon a time, indeed.

*

The Russian Novel of viral kid videos

When I last checked, “You poked my heart” had netted well over a million views, so the chances are several of you have already seen it. But it’s worth another look, because there’s just so much going on in it, especially in the developmental terms upon which we have been focusing (we are considerably further along toward the evolution of a fully social world, though still far enough back in that development to be able to make out all sorts of unusually frank and unabashed half-formed improvisations) and also because it’s just so richly pitched in purely narrative terms.

We are apparently in pre-school (perhaps early kindergarten) and, as we begin, a little boy in a white shirt is engaged in a fairly heated debate with a pair of identically green-bloused twin sisters over whether it is raining or sprinkling outside (as per their respective mothers’ characterizations). Probably best to just watch the ensuing developments for yourself:

“You poked my heart”

The boy, something of a mommy’s child, clearly has a crush on the more sophisticated sister (he can’t even stay focused on the subject at hand, in fact he can barely keep his pudgy little paws off her apple cheeks, at one point blurting out “You’re pretty” in midstream, only to double back in abashed embarrassment, preemptively deploying that old chestnut, “You’re not real, I’m real!” She on the other hand seems to positively relish lording it over him, at one point poking him right in the eye, and later on, of course, in the chest (“You poked my heart!” he reels, in devastated confusion). But he can’t get enough of her: at another point becoming so bamboozled that she’s got him being the one to insist it’s raining. Meanwhile, the other sister, the softer sweeter twin, seems to have her own actual crush on the boy, or at any rate keeps trying to smooth over her sister’s depredations (“Say sorry” “Let’s just go outside and see”).

And you can just imagine what Tolstoy would have done with this video, using it as the prologue first chapter to an 800-page saga, across which the boy would eventually marry the softer, sweeter, more devoted twin, only to regularly have his entire existence upended by the blithe occasional reappearances of her urbane vampy twin sister. (And how might the boy’s mommy’s role continue to unfold?)

*

Further along: the eternal fragility of developmental progress

This one you’ve almost certainly seen (it has been viewed over 143 million times since its recording in 2007, when its star was seven years old—the family reportedly netting $150,000 in royalties, which seems a bit low, but you do the math).

David After Dentist

Still, “David after Dentist” belongs in this trill in part because it exhibits the consolidation of several of the developmental trends we’ve been tracking in this series, but also because it illustrates just how evanescent they all can be. A few whiffs of laughing gas, and everything goes back up for grabs: “Is this real life?” “Arrrrgh!” “I have two fingers, you have four eyes.” “Why is this happening to me?” And “Is this going to be forever?”

Indeed, maybe that’s part of the video’s evident attraction, the shock of recognition at the way drugs seem momentarily to strip their recreational users of their most hard-won developmental certainties.

*

Coda: Two final primate instances

Piaget considered the development of a sense of object permanence—which is to say the awareness of the continuing existence in the world of a person or an object when it is no longer in the child’s direct field of perception—to be one of the foundational hallmarks of infant development in the first two years. What then to make of this little video of researchers seemingly playing a trick on a young adult orangutan?

For starters, it would appear that the orangutan has indeed attained object permanence to the extent that when its visitor plays the trick on him, making the permanent object actually appear to disappear after it’s been momentarily removed from his field of perception, the monkey seems initially confounded—what’s going on here?—but then suddenly seems to get it (oh, this is a joke!) at which point he keels over with exaggerated laughter (as if to prove that he is in on the joke). Second order astonishment: both that he has a sense of humor, and that he has a sense of self-regard (he wants it known that he’s no fool). Or not: this could all just be a stupid pet trick, the researchers over time (either intentionally or not) having trained the monkey to perform along these lines. It’s hard to tell, but still…

And then of course this famous experiment from Franz de Waal’s Emory University lab, as related during one of the eminent primatologist’s TED talks. The demonstration of how a capuchin monkey can display not just a theory of mind but a veritably Rawlsian theory of justice, an insistence, that is, on a sense of fair play.

I wonder at what age human kids begin to evince a similar sort of sense.

I’m sure some among you will know and, for that matter, you may have other such videos or narratives to add to this trill. If so, send them in to this address: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com, and we may make this into an ongoing feature.

* * *

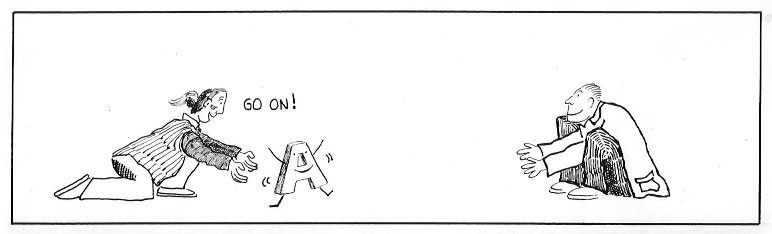

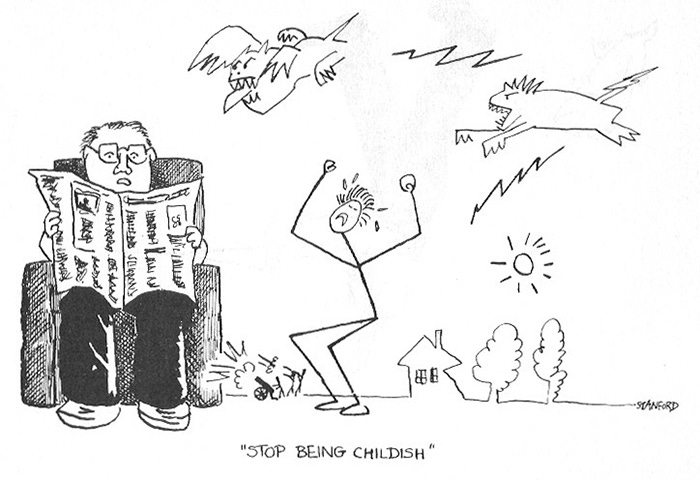

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

*

Animal Mitchell website.

* * *

FINAL CONVERGENT POSTSCRIPT

David “Animal Mitchell” Stanford’s drawing of “Baby A Learning to Walk” put me in mind of the Old Master drawing David Hockney considers the greatest single such effort ever put to paper, Rembrandt’s quick sketch of another child being coaxed toward its first steps.

Here is how he described it to me back in 2004, for a catalog essay subsequently included in my 2008 book, True to Life: Twenty Five Years of Conversations with David Hockney:

Hockney paused for a moment, content, his eye drifting about the studio.

“Take that picture over there,” he said, pointing over at a blow-up of Figure 1466 from his Benesch edition of Rembrandt’s collected drawings. (He had similar blow-ups of the same image pinned to walls all around the house.) “The Single Greatest Drawing Ever Made,” he declared flatly. “I defy you to show me a better one.”

A family grouping: mother and older sister holding up toddler boychild as he struggles to walk, tottering, toward his outstretched crouching father, a milkmaid ambling by in the background, balancing a brimming bucket.

“Look at the speed, the way he wields that reed pen, drawing very fast, with gestures that are masterly, virtuoso, not calling attention to themselves but rather to the very tender subject at hand, a family teaching its youngest member to walk. Look for instance at those whisking marks on the head and shoulders of the girl in the center, the older sister, probably made with the other side of the pen, which let you know that she is craning, turning anxiously to look at the baby’s face to make sure he’s okay. Or how the mother, on the other side, holds him up in a slightly different, more experienced manner. The astonishing double profile of her face, to either side of the mark. The evident roughness of the material of her dress: how this is decidedly not satin. The face of the baby: how even though you can’t see it, you can tell he is beaming. This mountain of figures, and then to balance it all, the passing milkmaid, how you can feel the weight of the bucket she carries in the extension of her opposite arm. All of it conveyed, magically. But look at the speed, the sheer mastery. The Chinese would have recognized a fellow master.”

A mother teaching her youngest to walk. One needn’t be an analyst to recognize the possible resonances that particular image might have held for this artist at this particular juncture in his life, a few years after the death of his own mother. That, and then as well: Father Rembrandt teaching Baby David to walk.

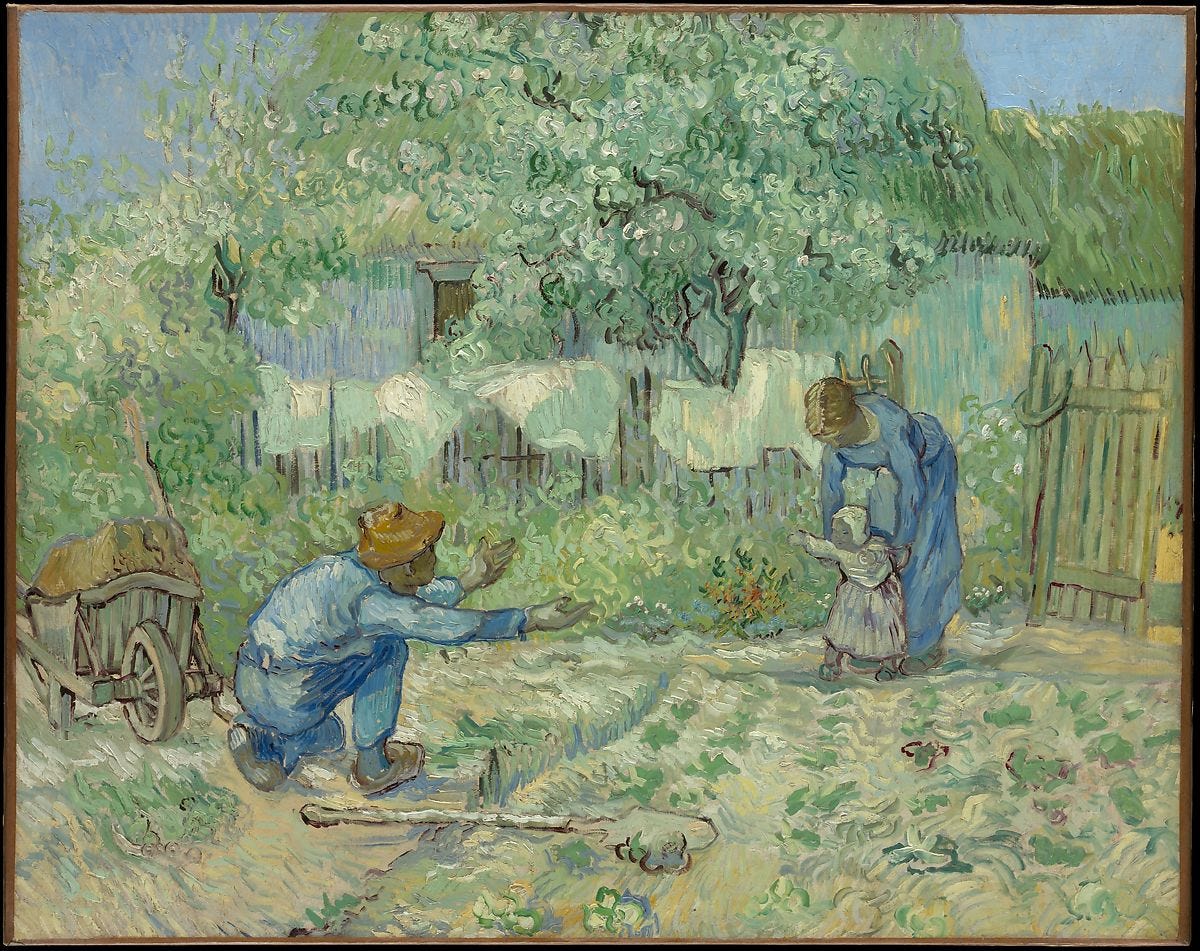

I asked our own David (Stanford) if he had had the Rembrandt in mind when he drew his “Baby A Learning to Walk” and he insisted that he had never seen the drawing before my having called it to his attention. “On the other hand,” he continued, “I think I was aware of the Van Gogh treatment of the same theme.” And he called that image, from the Met, up on his laptop

It turns out that that painting is called “First Steps, After Millet.” Which is to say Jean Francois Millet’s colored chalk and pastel sketch of 1859, now at the Cleveland Museum:

I’ll tell you one thing, though. I bet you Millet had seen the Rembrandt.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Ren tells the story of his Weimar-era modernist composer grandfather Ernst Toch, with a tintinnabulation of musical examples; and more…

* * *

We hope you liked this one, which was kind of different. And if you did, we really hope you’ll share it with your friends. Thanks!

We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

I love this issue, Lawrence. I'm introduced to your work by a mutual friend, Anthony Forma, and I'm grateful he did so. Especially liked the Hockney excerpt. Looking forward to the next installment! Chris Lapina, c.lapina@storymusic.co