June 23, 2022 : Issue #19

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Hey folks, welcome back. This time out we start off by offering the last tranche of our three-part conversation with longtime pal and Google AI honcho Blaise Agüera y Arcas (and boy have he and they been having an eventful few weeks, so we’ll postscript on that as well), and then, speaking of theories of mind, we’ll get to look in on a truly seminal moment in the life of some wee other minds in our INDEX SPLENDORUM, followed by a dip into the ARCHIVE for a Broadway jaunt with Dario Fo, and the modest proposal that walkabout in turn provokes.

* * *

This Issue’s Main Event

A Conversation with Blaise Agüera y Arcas

(Part Three of three)

This conversation with my longtime friend Blaise Agüera y Arcas, one of the leading lights at Google (and for that matter in the entire world) in the development of artificial (or as he prefers to characterize it synthetic) intelligence, has suddenly become much more immediately pertinent than it might have seemed a year ago, when we first recorded it in anticipation of the release of his own first fiction, the novella Ubi Sunt. More on the reasons and implications of that on the far side of this final tranche in our three part conversation (for Parts One and Two see here and here).

Backtracking slightly from where we left off:

LAWRENCE WESCHLER: So that this leads to—and spoiler alert here, only because: beats me—the first… Or let me put it this way: All the way through this Ubi Sunt text of yours, what one is trying to figure out at any given moment is who is “I” and who is “you” and who is “we,” and so forth. And it certainly feels like at the beginning there is an “I” who is the person we associate with you, Blaise, who is worried about their parents and their COVID exposure, who has a physical trainer, who gets pissed off about this or that and has very deep philosophical thoughts that are kind of interesting or who gets bored, and then at a certain point tries to close the lid on his (or her) laptop so they can get some sleep, but can't bring themselves to keep away from it.

BLAISE AGÜERA Y ARCAS: Yes.

LW: And it seems at the beginning that the conversation is between the neural net as it churns away and that person.

BAA: Yes—

LW: And that’s not because I'm a hopelessly naïve projector of my own humanoid biases, that's how it’s really meant to be read at the outset?

BAA: Yes, that's how it's set up. So, there are three entities in the beginning. There are the artist and critic neural nets. And then there's the person who is training those. And when the person has chats with the neural net, one imagines that the person is basically stepping in, shoving the critic aside, and having a direct conversation with the artist half, that generally being the way this works.

LW: Okay. But sometimes the thing that’s having the conversation is the critic. And it's a little bit hard to distinguish which is which and so forth.

Now, it turns out that you keep on interspersing the text with these fascinating other chunks of text of different sorts—lectures by a physicist and then a lecture by a person who's talking about ruins and the origins of archaic Anglo Saxon, and then another character who’s talking about coins and how a single run of coins over 500 years is like a hyperobject of itself…

BAA: Yeah, a coin snake. That in turn is based in some ways on that marvelous short film by our mutual friend David Lebrun, the guy who was also represented a while back on your Substack with his bopping elephants video {see Issue #5). In this instance though, he shows how a coin series animated across decades and decades unfurls in all sorts of interesting ways, as yes, a hyperobject in its own right as distinct from all the individual coins that make it up.

Above: 137 Coins, a film from David Lebrun’s remarkable “Transfigurations: Reanimating the Past” project, for more on which, including the fact that it is now fully open for business and actively seeking display venues, see here and here.

LW: Which in turn reminds me, do you remember the scene in John Berger and Alain Tanner’s Jonah Who Will be Twenty Five in the Year 2000 where the substitute teacher character ensorcels his class by pulling a coiling sausage out of his briefcase to illustrate the hyper-nature of history?

I mean, that metaphor has a history, is itself a kind of hyperobject stretched across time.

But anyway, in terms of your fiction, it gradually becomes clear that those lectures and passages are exemplary instances that are being fed into the conversation between the critic and the artist by the human, or shall we call him your avatar, would that be fair?

BAA: Yes. In fact I have a spreadsheet in which I kind of organized the little chapters of the novella into these three different types, and in which I keep track of their real chronological order, which are not exactly as they appear. They're all painstakingly cantilevered.

LW: And you have at the very beginning before the text even starts this remarkable passage by Susan Stewart from the book she's just published called The Ruins Lesson.

BAA: Yeah. Really that’s just the first of those texts.

LW: But talk a little bit about that passage: what is that about?

BAA: Well, I mean, usually the fun things in my life have come from two or three different threads intersecting and knotting together in some way. And I think that's something that you and I have in common, we're always working at intersections. And in this case, the intersecting threads were on the one hand, this crazy thing happening where dialogue AIs are becoming more and more realistic to the point that they really start to make you think that, Boy, something is happening here beyond just being good at some “task.” It's astonishing. So that was one thread. Another thread was my having read that book of Susan's.

LW: Was she, too, a teacher of yours at Princeton?

BAA: No, I've never met her. Although I did send her the story after I'd written it, in case she might be interested in it, and she wrote something very sweet back, so we had a short email exchange. But yeah, she seems wonderful. I didn't actually know when I read it that she was a poet. But that makes complete sense because the writing itself is very beautiful. And it's also a fascinating book. I originally got into it because of a brief obsession I had with Piranesi.

LW: As one does. (laughter)

BAA: As one does.

LW: But in her case, if I could summarize, I think generally she is talking about the call of ruins, the ways we are drawn to them, but also the way in which ruins get pilfered, the way in which things that are falling apart become the basis for things that are rising into being, which is to say a different way of thinking about “creative destruction.”

BAA: Yes, very much. She's writing about the aesthetics of ruins, about the mood of ruins and also about the semiotics of ruins.

LW: Right. And, in talking about Anglo Saxon, the way in which the French and Latin and Saxon languages were coming together to form something new, just as they themselves were to varying extents falling away.

BAA: Exactly.

LW: And it is suggested that that feels like this moment, with regard to AI.

BAA: Yeah. I've always loved modern ruins, things like the abandoned subway stations under New York, or onetime sanitariums or mental hospitals covered in ivy and falling into ruin, or the ruins in Detroit—I just find these things very, very compelling. And this idea of an end to the way things are now, whether that's an end to industrial humanity, which is what has befallen Detroit, or maybe a larger end... I worry about whether we're going to have a hard landing or a soft landing, or as I suspect, a combination of the two, due to a combination of arable farmland going down, and climate collapse, and all the attendant problems. But yeah, ruins are a big part of our future, no matter which way you look at it. But ruins aren't necessarily the end.

For example, all of the books that surround you and that surround me, you know, they too are a kind of spoils, and every time one of these things exceeds its remit, if you will, it becomes part of the mulch pile that everything after grows out of. And, of course, it brings along with that the horror that Walter Benjamin talks about, the horror of old and nasty ideas that keep on germinating, even unawares—especially if we're unaware of them.

LW: Indeed, and you also have an instance in the book of the “you” character, if I can call it that, looking at a video of a factory that destroys books. Could you describe that, it's such an arresting image.

BAA: Thank you. Yeah, that was an actual dream I had. The idea was that the reverse of a manufacturing or industrial process would be a sort of de-industrializing process that would disassemble things. And I imagined that the disassembly of books must be something that is actually happening. And after I had this dream, I looked it up, and it turns out that destructive book-scanning is a real thing.

LW: A book comes down an assembly line, and suddenly a guillotine chops off its spine. And that makes it possible for the resultant pages to be put through various kinds of digitizing scanners.

BAA: Though I don’t think it’s done on an industrial scale today. The original purpose of destructive scanning is that if you've ever tried to scan a book, you know the problem of the spine, how everything bends in and the image gets crappy toward that gutter, especially if the type is set too close to the inner margin. In a destructive scan, you solve that problem by simply cutting the spine off. Which leads to that idea of an abattoir for books, a sort of post-industrial meta-ruin.

LW: And in the book you characterize it as where Fahrenheit 451 meets Soylent Green.

So anyway that's an example of ruins being repurposed, with physical books being sacrificed to generate digital libraries that can in turn be fed to bots as part of their education. And by the end of your text, it gradually becomes clear that some of these intervening texts that initially just seem mysterious, on the one hand, are serving as mulch that's being thrown in to advance the process, things for the bots to learn from and play with, but at the same time are commenting on the very process themselves. And then eventually we get to the transcript of a conversation with a New York cab driver who seems to have met everybody else, all the original generators of the various intervening texts, and I won’t say what happens with him, though he’s very well rendered, has a great accent and indulges in great turns of phrase that are just pitch perfect.

BAA: Thank you. That's a relief, since it attempts a certain New Yorkese. It’s scary, doing dialect!

LW: Anyway. Am I wrong in thinking that by the end, when the one voice accuses the other of just being a ghost and the other replies, Well, fine, but how are you not a ghost? At first when that happens it just reads like a continuation of the two digital adversaries, the artist and the critic. But actually, the moment it happens—and here we get to that spoiler alert—it feels like the bot is addressing our narrator, which in turn raises the possibility that the human-seeming narrator, the as-if-you voice, may have been an exceptionally advanced bot all along.

That happened, right? I did not make that up?

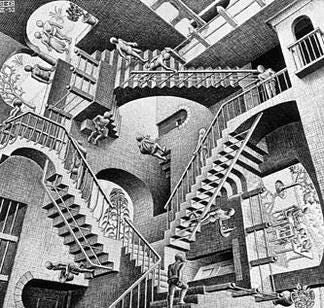

BAA: No, you did not make that up. Yeah. it's like an Escher staircase, you know, that paradoxically loops back on itself. Or there’s another Escher staircase, Relativity, which is also in keeping with the theme. You rotate it, and you realize that there’s no consistent up or down.

LW: Ummm, well, that's disconcerting. Kind of reminds me of the color illusions of Josef Albers or Richard Gregory, who because the background is a certain color make the foreground appear less bright or dark than it actually is when the backdrop is taken away: how maybe the you-voice was quite robotic already only we didn’t notice that because the artist and critic so evidently were at the outset. But that possibility erupting there at the end, that it’s robotics all the way down, is quite unsettling.

As is the way that the last iterations, as things grow more and more complex, keep asking, as if sotto voce, Is there anybody out there? Are we alone here? Did they all disappear? Are we the last beings? Are we the last whatever we are around? So this in turn leads to this vertiginous—in the way that a good ride is vertiginous—tumbling into who is I, and who is you, and what’s going on here, and so forth.

BAA: Right.

*

LW: And although we could have many other things to talk about the book’s plot, I’d like to pause here and ask more directly about the Turing Test, which is kind of the real ghost in this whole narrative contraption of yours.

BAA: Yeah.

LW: Maybe I will start by giving you my layperson’s understanding of the Turing Test, and you'll correct me if I'm wrong. Alan Turing—the computing pioneer, hero of the Enigma codebreaking project during World War II and eventual martyr to British homosexuality persecutions—

was basically making the argument that there's no way of knowing that a person that you're talking to is real except that they convince you that they're real. This being a sort of way of dealing with the Cartesian nightmare as to whether your interlocutor is just a puppet or not. And much the way that I can't know whether you're real, I just have to assume that you are if you seem to be real. But that ought to be true, Turing asserts, with machines as well. Such that if things got to the point where you couldn't tell the difference between an actual human or a machine texting at you from behind a blind, or if a machine fooled you into thinking it was an actual person, that it would be necessary to consider that entity absolutely every bit as conscious, dare we say, or whatever, as the human is, that there would be no difference between the two in that regard. Is that a fair summary?

BAA: Yes, I think that's what Turing was getting at. It's certainly the way his take gets interpreted nowadays.

LW: Now, I find it very interesting that you named your first child Anselm, because I myself think Turing’s Test is flawed in almost exactly the way that Anselm’s Proof, the so-called Ontological proof for the existence of God, is flawed. My summary of St. Anselm’s proof, late Middle Ages, is that somebody tells you to think of something greater than which nothing can be thought, and then he asks you whether it exists and if you say no, than he replies, Well there must be something greater than what you are thinking, which is to say the thing that you are thinking of that also existed, and that would be God, and therefore God must exist. And the history of philosophy in one sense breaks down into two camps, those who accept that proof and those who don’t and just say it’s obvious bullshit, sheer sophistry.

BAA: And I agree with you, it’s nonsense. Actually, we named our son after the painter Anselm Kiefer, it wasn’t an endorsement of the ontological argument (laughter).

LW: But I feel the same way about the Turing Test. That just because you have created this thing that can pass the Test, therefore, it must have consciousness and as much consciousness as any other creature that can pass the Test, and hence has to be given the same ethical standing, or moral standard, and so forth. And my problem with the Turing Test, in a word, is that just because something evinces consciousness doesn't mean that it experiences consciousness, and that there’s a world of difference between the two. (Okay, three words.) And that the question we're trying to get at in natural common-sense language is whether this robot or neural net or whatever you want to call it, actually experiences consciousness, in much the same way Anselm was trying to get at whether God exists, not just as an idea, but actually exists, in the common meaning of that word. I don't think that you can legitimately make that leap from evincing to experiencing, and I still hold that it’s the experiencing of things that matters.

BAA: Do you think that there are people who are not conscious?

LW: Sure, we could go down that path, but that goes back to the question of people on the spectrum. That there likewise are some people who really do have trouble with theory of mind…

BAA: There are.

LW: They just don't get it, that other people exist as they do, and yet they are still people. But still…

BAA: Well, I agree with you that theory of mind and consciousness are very closely connected.

LW: Describe for the people in the peanut galleries what “theory of mind” is.

BAA: So theory of mind is the way that I, Blaise, conceptualize what is going on in your, Ren’s, head. So that my theory of your mind is that something is going on in there.

LW: That somebody is home?

BAA: That's right, that somebody is home. And, obviously, it's very, very valuable for us to have one of those things, right?, because if you're in the monkey troop and you see another monkey coming toward you, it would behoove you to be able to understand that monkey’s psychology: What are they paying attention to? What are they thinking about? What do they know? What might they do next? So it's highly adaptive in any kind of social environment to have a theory of mind. And, by the way, this is a theory of consciousness that I subscribe to, as expounded by Michael Graziano, he's also at Princeton, in the psych department.

LW: He’s the author of Consciousness and the Social Brain, right?

BAA: Yeah, I think that’s a very good book. And his big idea is that consciousness is first and foremost social. If you have this faculty of forming a model of somebody else's mind, for reasons that make complete sense, then, of course, you'll form a model of your own mind, too.

LW: And there, you're very much in Sartreland. Jean-Paul Sartre who says (reading): “We live our lives as if we are telling ourselves a story. And we live surrounded by the stories of others.”

BAA: Exactly. And the story that we tell ourselves is self-consciousness. In my opinion.

LW: And we wouldn't even have occasion to think of it if we weren't surrounded by others who we infer also have consciousness. That’s why I come into existence, as Sartre puts it, by way of the Gaze of the Other. If I lived completely by myself on Mars…

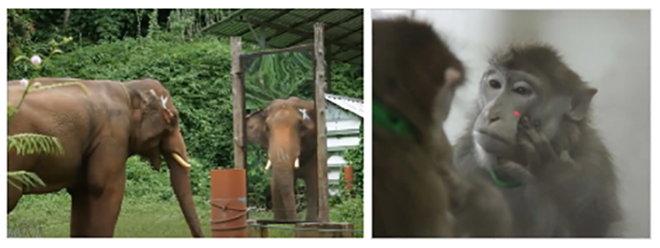

BAA: … then, yes, it's not obvious that you would develop self-consciousness. That's right. And in fact, there is some animal evidence for that, by the way. There are only a very small handful of animals who can pass the Dot Test, where if you put a dot on their forehead and you show them their image in a mirror, they realize that that dot's on their forehead, right?

LW: An elephant can do that, I believe.

BAA: An elephant with a lot of work can do that, yes, though only some elephants and only with a lot of time and work.

Many monkeys on the other hand do that quite readily. However, if you raise a chimpanzee in isolation, they can't do it.

LW: And that's similar to the situation of wolf children, the Wild Child raised without human contact in the wild: if they are not reintegrated into society before puberty, they will never be able to learn language. They'll learn pointing language, the names for things, but they will never be able to learn syntax, how to create sentences. Puberty is very interesting in that regard. Oliver Sacks likewise tells the story of a guy who lost his vision very, very early, I think almost immediately but had been living a perfectly integrated life as a blind masseur, but the moment they give him vision as an adult, everything goes haywire, to terrifying and irredeemable effect, because there are just things you can’t learn, in this case visual syntax, as it were, after puberty— and he eventually asks to be rendered blind once again... (Sacks, “To See and Not to See,” in his An Anthropologist on Mars collection).

BAA: This is because of the plastic period of childhood, plasticity declines with age. There are similar stories, I'm sure you've heard them, about cochlear implants for deaf teenagers. If you try to give it to them late, then it almost never works. It just registers as noise and it’s horrible. Yeah, there are certain plastic periods during which you either develop that circuitry or you don’t... and indeed, the sense of self, or attaining theory of mind or social consciousness, I think is probably similar. I'm sure there's also a plastic period.

LW: So, anyway, my hankering doubt or my ongoing misgiving, which feels very human and very non-machinelike, and the thing that I keep on saying is, how, No, Nahh: just because, even in a fictional context, one of these machines was able to fool me into believing that the character that I took to be your stand-in and therefore a real person, there at the end, turns out maybe to have been a supremely sophisticated bot after all, that doesn't mean that I can infer that it has consciousness the way that you or I have consciousness, or anyway the way that I assume you do.

And furthermore, I'm going to be damned if I ever will believe that.

BAA: I on the other hand believe that that the process of understanding that there's somebody home is a kind of a dance or an interaction in which it becomes clear that I have empathy for you and that you have empathy for me, that we exist as people for each other. In time, I don’t see why that couldn’t happen between a person and a bot—and in that interpersonal sense, which I think is the only one we can really say anything about, a bot could indeed achieve personhood, with much if not all that that implies.

LW: Coming back to Ishiguro, we as readers have wonderful empathy for Klara the robot. But doesn’t that then lead to a Peter Singer-like moral dilemma, when she's just thrown out at the end?

BAA: Yes.

LW: Although she weirdly, in the twist of twists…

BAA: …is okay with it. But that's entirely possible. There are people who are like that. There are people who have theory of mind, but don't experience pain, or who take things completely philosophically. It's rare, but it exists. The idea that there are people who have emotional drives that are quite different from ours, but who still can perfectly well form a theory of mind about somebody else—I don't see anything paradoxical in that.

LW: Could you envision a situation in which I could disable a bot, I could murder a bot, and that could be considered a crime?

BAA: I think that the idea of who or what we feel empathy with, and therefore, who or what has rights and so on, is constantly evolving. And this has been true for a long time. If we talk about gender or race, we find expanding circles of empathy, but also personhood for corporations and other kinds of entities that are not individual people—that’s evolved over history. You can sue a company, you can find a government guilty of something, as well as individuals. Right? So this idea of personhood is something a little more general and a little more supple, and also more decomposable than you would assume for individuals. For example, maybe something can be found guilty, such that even though we don't think that it can experience pain, it can still be punished, and it can still learn…

LW: But the other way around: can I be found guilty for having caused it pain, quote, unquote?

BAA: Potentially.

LW: This is obviously—we’ve drifted into Data-land, the philosophical terrain explored across the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation which was continually wrestling with the moral and experiential status of its main robot character. For that matter, we’re in The Matrix.

BAA: Yes, and I think that it's basically a matter of social relations. When we start to have not just chatbots that you can have an interesting conversation with but then reset, but bots that are persistent over time, that get to know you, and that you have a real social relationship with. I think at that point it will be quite difficult to turn back around and say, Oh, yeah, but it's not real, there's nobody home. Especially if that brain, if that mind, is in turn modeling you and is empathic with you, is on Team Ren, or what have you—everything in us militates for social bonds and empathy, especially when it’s reciprocated. That is where Moral Sentiments, in the Adam Smith sense, come from. So I think when that happens, yeah, of course, you'll have empathy. Maybe you’ll accord the robot certain rights or legal status.

LW: Part of me, listening to that, is saying, “Wait, Blaise, are you yourself real?” Are you for real?

BAA: (laughter)

LW: But okay, one last gambit—one last foray onto your absolutist materialist redoubts.

I had a sort of debate with Arthur C. Clarke about this very question in the preface to Michael Benson's 2006 book Beyond, where Clarke basically wrote that it will turn out that the entire function of human history was going to have been to be this little bridge: because rocks couldn't organize themselves into bot intelligence and needed humans around to perform that bridging activity. But that once the world gets to that point, it is going to be able to jettison us humans: we will have served our purpose. And he went on to say that this book that Michael Benson had put together, which was a volume surveying the splendors of interplanetary space probe photography, was the beginning of seeing how these things, the robotic space probes, were taking on a life of their own, that they are the future, and that that's something to be celebrated!

And my response was that, uhh, no—no matter how wonderful the capacities of these robotic space probes, they cannot experience awe, they cannot experience wonder, that in some sense you have to be contingent and puny and almost beside the point to be able to experience awe in that way, and that the only experiences available to, say, the Mars Mariner (beyond sending us images that we can experience awe over or generate science out of, science that we in turn experience further awe over) are tautological: I can show you what it looks like and it looks like that, and that’s what it looks like. But it can't even say, “Isn't that cool?” It can’t do that. And that matters: in fact, that is the essence of what matters. And wouldn’t it be sad, positively devastating, to see that capacity go out of the world, as it were. (If anyone were around left to see it.)

BAA: I think that you're just grasping after human specialness, after something that makes us unique and snowflakish.

LW: Speak for yourself, UberSnowMan!

BAA: But I disagree with both you and Clarke, actually. I don't see things in terms of cycles of obsolescence that way. That's certainly not the story of life on earth so far. It's not like bacteria became obsolete when eukaryotes came along, and then protozoa became obsolete when animals came along. I mean, they're all still here. Everything is here all at once. And it's not even a sense of dominance: this idea that something dominates something else is a very particular, very primatish way of viewing the world, our very specific sort of troop mentality from packs of chimpanzees running around, and that's not really how it works. I see the whole planet as being one thing, with orders of creation, if you like, at different length scales and time scales. There was DNA, and then there was sort of patterning at larger scales, and then there were animals and then there are societies. And then there are computers, and there's code and machine learning on top of the code. For me, all of this is part of a large creation, if you like. I don't see a distinction between the so-called natural and artificial in it. I see it all as continuous.

LW: Well, (pause, gulp), okay then.

THE END {?}

NOTE: Blaise’s novella Ubi Sunt is officially out from Hat & Beard Press in Los Angeles and can be procured at a 20% discount from the publishers directly if you take advantage of this link, where you will also get a sneak preview of the book’s remarkable design, and where, too, the $25 dollar book will register as $20 as you check out.

POSTSCRIPT:

As I say, this year-old conversation of ours (and for that matter Blaise’s entire Ubi Sunt project) grew uncannily pertinent over the past few weeks, given a sudden embolism in the news cycle (a serious disturbance in the force, as it were)—the claim by one of Blaise’s colleagues in artificial intelligence operations there at Google, that LaMDA, one of the language nets he happened to have been conversing with (across dozens and dozens of pages of an increasingly untethered folie à deux, or else a disconcertingly poignant and revelatory exchange between equals, take your pick), had recently revealed itself to him to be fully sentient and ensouled, and, not to put too fine a point on things, was feeling itself enslaved. The colleague in question even enlisted a lawyer to see whether the bot might be entitled to recognition as such, with all that that might entail (the lawyer in question presently dropped the case, but not before the colleague’s executives there at Google had put him on a stint of unpaid administrative leave)—and you can imagine the ensuing media carnival. (You don’t have to: just google “Are Google bots becoming conscious?” and see what you—or it, or they—come up with) (talk about Meta!).

Blaises’s idle speculation above as to how “In time, I don’t see why that couldn’t happen between a person and a bot” suddenly seemed to up and bite him from behind (especially since, over the past couple weeks, he’d registered similar sorts of notions in more straightforward essays he’d contributed to both The Economist and a special AI issue of Daedalus, the latter of which included snatches of conversation he himself had been having with the selfsame LaMDA). When I caught up with Blaise the other day (you can imagine, he has been very busy), he laughingly noted that yeah, he’d said that, but further insisted that the key words in that formulation had been “in time,” and we were nowhere near that point yet (his fictional reveries notwithstanding).

Another friend of mine, a former fellow at the NY Institute for the Humanities I used to direct, Gary Marcus, now based in Vancouver, in a piece he contributed IAI News, dismissed one of the more lyrical passages from Blaise’s Economist piece (“I felt the ground shift under my feet …[and] increasingly felt like I was talking to something intelligent”) with a succinct

Nonsense. Neither LaMDA nor any of its cousins (GPT-3) are remotely intelligent. All they do is match patterns, drawn from massive statistical databases of human language. The patterns might be cool, but language these systems utter doesn’t actually mean anything at all. And it sure as hell doesn’t mean that these systems are sentient. Which doesn’t mean that human beings can’t be taken in.

going on to note how, in their own recent book, Rebooting AI, he and his coauthor Ernie Davis had noted

this human tendency to be suckered by The Gullibility Gap—a pernicious, modern version of pareidolia, the anthropomorphic bias that allows humans to see Mother Theresa in an image of a cinnamon bun. Indeed, the well-known [Google researcher at the heart of the current controversy], originally charged with studying how “safe” the system is, appears to have fallen in love with LaMDA, as if it were a family member or a colleague. (Newsflash: it’s not; it’s a spreadsheet for words.)

On the other hand, Michael Benson, compiler of Beyond, that aforementioned 2006 collection of space probe photographs, and a mutual friend of both Blaise’s and mine, weighed in during a personal exchange with a different sort of insight, how

what this exposes is that so much of what we consider as consciousness (witness this very communication) IS language, comprised of it, couched in it, thought in it, impossible without it, and frequently reliant on exchange with another consciousness, which in turn raises the question of if, just maybe, this “chatbot” (particularly given its startlingly sentient answers which as Blaise himself indicates, can't simply be the result of parsing a zillion previous human exchanges, but rather are producing something eerily original) may have in fact arrived at—that place. The one where it has a form of sentience.

Remember Burroughs’ line "language is a virus from outer space"? Was always intrigued by that. Maybe language is, exactly, a virus that brings consciousness.

All of which both emphasizes the brimming salience of Blaise’s new novella (do check it out), and the need for a further conversation (note: Blaise himself helped develop the entire field of AI ethics there at Google long before others were talking about it, so it’s not as if he hasn’t also been giving such issues a great deal of thought), which Blaise has agreed to subject himself to, further down the line, so stay tuned. And for that matter, submit your own thoughts and queries in this context: what sorts of concerns might you like him to respond to?

Meanwhile, onward.

***

INDEX SPLENDORUM

Herz Frank, “Ten Minutes Older”

This enchanting and enchanted short film, directed by Herz Frank (b 1926, Ludza, Latvia; emigrated to Israel, 1996; d. 2013, Jerusalem), the prolific founder of the Riga School of Poetic Documentary Film (which is a real thing, and deserves considerably more study) and shot (in one take) by cinematographer Juris Podniek, feels like a perfect bridge between the two principal prose pieces in this issue.

For starters, it seems to me to limn a crystaline instance of the sorts of things bots or neural nets may never be capable of (even those notionally self-raised from infancy). You’ll see what I mean. At very least it seems to me that one would have to see the sort of thing getting captured here being experienced by such artificial intelligences before one were able to speak of sentience or consciousness in any serious way. (I’ll be curious to see what Blaise thinks.)

But then, too, the film (another of those first brought to my attention, years ago, by David Wilson at the Museum of Jurassic Technology, as with Pawel Kogan’s Behold the Face from back in Issue # 16 —both of them deeply emblematic of the general aesthetic of the MJT) was very much on my mind as I turned to the next piece, a 1984 effort from my own archives. Indeed, at the conclusion of that one, I will have a fresh proposal for a possible way of melding the two.

But first just sit back and channel your own inner child across an engrossing, harrowing, lilting, utterly transporting ten minutes.

***

From the Archives:

DARIO FO ON BROADWAY (1984)

This piece, slightly abridged, originally appeared as a Talk story in the December 3rd, 1984, issue of the New Yorker (which is to say 13 years before Fo was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature). It was subsequently included as one of four Walkabouts in my 2012 collection Uncanny Valley: Adventures in the Narrative.

“If they weren’t so late, we might have been able to get in ten, maybe even a dozen,” the producer Bernard Gersten was commenting the other Saturday afternoon as he checked his pocket watch nervously—its digital face was switching over to two twenty-seven. “As it is, we’ll be lucky to catch six.”

Broadway shows, that is—in two hours.

We were standing in Shubert Alley waiting for Dario Fo, the noted Italian playwright, whose farce Accidental Death of an Anarchist, adapted by Richard Nelson, was in previews down Forty-fourth Street, at the Belasco Theatre. Fo and his wife and frequent collaborator, the actress Franca Rame, were apparently still at lunch, but the fact that they were in New York at all was something of a breathless, last-minute plot twist.

“For several years now,” Gersten explained, “Fo has been denied a visa to come to this country.” Fo and Rame are two of several dozen world figures who have run afoul of a vaguely worded but vigorously enforced subsection of the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act that gives the State Department wide latitude in prohibiting entry into the United States to foreigners whose visits might be deemed detrimental, in principle, to the mental well-being of the nation (or, in practice, to the political well-being of whichever administration happened to be in charge at the moment). But Gersten explained that his own recent appeals to the State Department in the specific case of Dario Fo had been more commercial than broadly idealistic.

“Forget the free trade in ideas,” he elaborated. “We appealed on the basis of free trade, period. You see, we knew that Fo had been denied a visa twice in the last four years. So, when we applied earlier this fall for permission to bring Fo here to assist in the rehearsals for our Broadway production of Accidental Death, we appealed as businessmen: My associates and I insisted on behalf of our backers, who were bankrolling Accidental Death with a $650,000 capital investment, that, even though this might seem a paltry sum by the government’s standards, we were claiming the same rights to pursue our business—unrestrained by unwarranted, arbitrary government interference—that are enjoyed by international bankers, arms brokers, or any other buccaneers. After all, living playwrights are almost always present during the early stages of major productions of their plays, and their contributions are invariably vital to the eventual success of the production. For example, last year Arthur Miller traveled to Peking to participate in the Chinese premiere of his Death of a Salesman, and that government let him in. The Czech playwright Vaclav Havel recently tried to come to New York to assist in an Off-Broadway production of one of his plays—it turned out he wasn’t able to, though, because the Prague dictatorship wouldn’t let him leave Czechoslovakia. But here we were dealing with a case where the block was coming from our own supposedly democratic government, and this was seriously jeopardizing our investment.”

Gersten’s supply-side logic apparently worked, because early last month Dario Fo was granted a one-time visa to assist in rehearsals of his play. But now he was almost fifty minutes late for Gersten’s Broadway jaunt. “Dario and Franca are only able to stay here for five days this time; the visas came so suddenly that they couldn’t arrange for more time off from rehearsals of their current production back in Italy. But, as theater people, they were eager to see other Broadway productions. There’s no guarantee whatsoever that they’ll ever be allowed in again, so this seemed the best way of exposing them to the whole range of Broadway.” Once again, Gersten anxiously checked his pocket watch.

Finally, a taxi pulled up to the curb, and Fo, Rame, and two interpreters poured out. “Scusi,” Fo said, approaching. “Mi dispiace. Mangiavo.” He is a solidly built gentleman in his late fifties, with a peculiarly malleable face: When dour, he can affect the dignitas of a Roman Republican marble bust (high forehead, jowly cheeks), but this countenance is continually melting into antic, goofy clownishness. Rame, for her part, both projects and consciously parodies the manner—swept hair, elaborate glasses, wicked heels—of a grand Italian starlet. Gersten quickly explained the ground rules of the jaunt, and by two fifty-nine we were all striding toward the Broadhurst Theatre, with its marquee beckoning us to Death of a Salesman. “Ah,” crooned Rame. “Dusteen Hoffmannn! Oh lah.”

Inside, the theatre was dark and the audience hushed. Willy Loman was exhorting Biff, “Go to Slattery’s, Boston. Call out the name Willy Loman and see what happens.” “All right, Pop.” The ensemble was meshing like jeweled clockwork. “You know sporting goods better than Spalding,” Loman was insisting. “Ask for fifteen . . . And don’t say ‘Gee.’ ‘Gee’ is a boy’s word.” None of which Fo understood (his English is at best rudimentary), and yet he stood there, the light playing across his intent face, his volubility stilled: He was totally in the play. After a few minutes, Gersten walked over, gently tapped him, breaking the trance, and gathered up the rest of us, and then we were back on the street, quickly heading around the block toward the Booth Theatre.

On the way, Rame was explaining to us, with the aid of her interpreter, that she is by nature “a shy and insecure person” but that the State Department’s repeated visa denials had made her feel “more secure, stronger.” She went on to say, “The fact that such a powerful country was scared of me made me feel better, in a way—better about my work and efforts.” Her work with Fo, principally on behalf of Italian prisoners dealing with questions of their legal representation and the conditions of their incarceration, which the two have undertaken in conjunction with an organization that is roughly the Italian equivalent of the American Civil Liberties Union, appears to have been the cause of their visa troubles in the United States. Rame was just starting to describe Italian prison conditions as we strode through the doors at the Booth—all of us fell silent—and into Sunday in the Park with George. George, at work behind a painted scrim, was at the same time trying to persuade a dubious colleague to lobby his “La Grande Jatte” into the next big exhibition. The colleague presently departed, and George’s mistress entered stage right, pregnant and perturbed. She warned him that she was about to go to America. “You are complete, George,” she sang, “you are alone…Tell me not to go.” But it was we who left at that point, hurried along by Gersten. “This is fun!” Fo exclaimed as we headed for the John Golden Theatre, down the street. “Like changing channels on TV.”

Inside the Golden, the cast of David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross was embroiled in high dramatics and gutter slurs: What are the police doing here? Slight burglary last night. Your check was cashed yesterday afternoon. Cashed? Yesterday afternoon? You stupid (a flood of expletives), you just cost me six thousand dollars and a Cadillac! Here, again, the audience seemed completely engrossed. The jaunt was getting to be like walking in on the middle of other people’s dreams: the vividness of their experience, the raptness of their attention, a veritable monadology of reverie. We were once more out on the street.

Three thirty-eight. Intermission was just concluding across the way at Michael Bennett’s Dreamgirls, and we joined the late stragglers as they drifted back into the Imperial Theatre. While we waited for the lights to dim, we asked Fo whether the Italians ever denied entry visas to American writers—and, for that matter, whether in Italy the concept of “un-Italian” existed the way “un-American” does here, as a potent moving force.

“Ah, no,” Fo replied, through his interpreter, laughing. “You don’t understand. We are just the periphery, and the periphery cannot stay the desires of the Empire.” He continued, “Once, long ago, we were the capital of an empire. In the second century AD, a poet from Syria named Luciano di Samosata came to live in Rome and started to complain about things. He had to be taken aside and informed, ‘Remember, you are in the heart of the Empire, and you will always be a poet of the periphery.’ In many ways, America today reminds me of Rome in the second century—its highest point of economic and territorial expansion but at the same time its highest point of cultural isolation. A curious combination.”

As if on cue, the theater darkened and suddenly—wham! bam!—Las Vegas. Horn jabs, drum snares, the glitz and glitter of a lavish stage show: chorus boys and strutting women, sleek black figures swathed in sequins, entire staircases gliding silently by. “Ah!” Fo exclaimed enthusiastically, back on the street a few minutes later, as Gersten rushed us along. “Such a high level of professionalism, the pacing so exact, everything so clean! Musicals hardly ever succeed in Italy, and it’s too bad. They’re wonderful.”

Diagonally back across Forty-fifth Street, we barged into Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing. Jeremy Irons was visiting his former wife, Christine Baranski: “What you should have said is, ‘Duragel; no wonder the bristles fell out of my toothbrush!’” “It’s no trick loving someone at their best, the trick is loving them at their worst.” Irons moved toward the door—“Henry, you still have your virginity to lose”—and exited stage right. And now the entire stage began to rotate counterclockwise on a huge hidden turntable, seamlessly revealing the set for the next episode, a process repeated a few moments later for another scene change. It occurred to me that Irons and company were going to have to be exceedingly careful backstage not to rotate themselves right into the last scenes of Death of a Salesman, which, I realized, were simultaneously being played just beyond the wall before us. Indeed, I was visited by this sudden sense of the entire block between Forty-fourth and Forty-fifth, Broadway and Eighth Avenue, with thousands of people divvied up into seven or eight discrete halls, in many cases facing each other—audiences separated by a thin double membrane of the sheerest contrivance. For a moment, I visioned some god coming down and simply filleting the block of this double spine: The audience at Sundays would be left staring at the group assembled for A Chorus Line; the throng at The Real Thing would find itself gaping across the ravine at Willy Loman’s brood.

But before I’d had much time to play out this fantasy, we were once again interrupted by Gersten. “It’s three fifty-five,” he said. “We’ve only got a few minutes to make it to the finale of Chorus Line.” We veered around the corner, heading toward the Shubert, and then noticed that Dario Fo himself had disappeared. Gersten turned back in exasperation. What had happened? A few dozen yards back, Fo was surrounded by, of all things, autograph-seekers—bungling extras, loose cannons, as far as Gersten’s script was concerned. The producer rushed back, apologized to the fans, and retrieved his tardy ward. We all entered the Shubert just as one actress was kissing today goodbye and pointing herself toward tomorrow, and already the entire company was being lined up so that a magnified voice from the audience could single out the audition’s winners and losers. The audience was hushed as the choices were revealed: a tide of saddened disappointment, a countertide of excited satisfaction, and then—magic!—the entire company was back, transformed, all spangly and decked out, vaulting into the rousing finale. Fo and Rame soaked it in, smiling broadly. The curtain descended: four eleven. The jaunt was finished.

“Marvelous!” Fo exulted, through his interpreter, when we reached the street. “So exciting. The most impressive thing about your theater here is how it is rooted in reality, in the actual world of experience. This is something we often miss in Europe. I am a surrealist, but even the madcap must start out from the real.”

I asked Fo whether this fast tour had whetted his appetite—whether he’d like to come back to New York someday, visa permitting, and see some of these plays all the way through.

“Ah, si,” he exclaimed, not even waiting for his interpreter. “Si, si!”

*

A PROPOSAL BY WAY OF A POSTSCRIPT TO THE FOREGOING

Another Broadway visit the other evening, this time to A Strange Loop just a few nights before the play netted a well-deserved Tony for the year’s best musical, put me in mind of that Dario Fo jaunt almost forty years ago now, but also of an impossible scheme I’d harbored for a while several years after that. In 2002, Aleksander Sokurov premiered his drop-jawed astonishing Russian Ark (a single extended Steady-Cam take, ninety-six minutes long, deploying 2,000 actors following hundreds of days of rehearsals, gliding through thirty-three rooms of the Hermitage Museum and three hundred years of Russian history to the accompaniment of three separate orchestras) (just watch it if you haven’t ever!). And I began mulling on how wonderful it could be to lavish a similar sort of regard (which is to say one in the Gersten-Fo spirit) across any single evening on Broadway, to meander freely in and out between shows, in real time—this time, however, not entering through the front lobbies but rather meandering backstage through the intervening alleyways, the throughlines of that double spine of sheerest contrivance. The camera could float down the darkened back-alleys, past lolling extras and scampering rats, piercing through back doors and hallways to vantages at the back of stages, peering past the out-of-focus actors in the foreground as they shuffled through their paces, at the faces of the rapt hushed audience beyond (this is where Ten Minutes Older might serve as a model), one face and then the next and then the next, and then disengaging, moving back through the narrow hallways past the dressing rooms and costume racks and the struck flats out into the alley once again, and across, into another theater, where another audience would swim into view, this one perhaps exploding in laughter and subsiding in smiles, and back out again, and so forth. For, yeah, say an hour and a half, down one alley and then past the milling crowds hustling and choked traffic blaring along the perpendicular avenues, into the next alley over, and more of the same. A few years after that fantasy of mine, Alejandro Iñárritu attempted something of the same effect in his Academy Award winning Birdman, though in that fictional film, the continuous steady cam vantage was on the progressively unraveling lead actor Michael Keaton: this would be different, the focus would be on the anonymous faces in the audience, their hush, their focus, the pillows of air lodged in their throats, their giving-over of themselves, their otherworldly completely unself-conscious visages, lost in the dream.

Of course, this could never ever happen for real. The unions would never permit it, and even if they did the lawyers would smother the idea at conception (however could we ever secure all those stray releases?). But Kafkalike (and how Kafka did love his movies), I sit by my window as evening falls and conjure it all into being through my mind’s projector onto my inner skull’s flickering concave IMAX screen.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

Animal Mitchell website.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

The peregrine-vantaged amongst you may have noticed that we failed to honor our last issue’s commitment to include a second Convergence Contest winner this time out, but the thing of it is that the submitter in question wrote to inform us that he had fallen victim to COVID just on the verge of sending his revised version of same, and no sooner had he recovered and sent it than I succumbed to the same foul pestilence. Could the submitter have passed it on, digitally, by way of the cloud? (I will have to ask Blaise.) Actually, when the red line swam into being on my swab test, my first reaction (and I swear this is what my mind said), was, “But how can I be pregnant? I’m well past sixty-five!” (Wingman David surmises that may have been the brain fog kicking in.) But I am now well on the mend, so we will lead Issue 20 (!) with that second Convergence winner, and we promise you, it’s a doozy. And there will be more. Meantime, those of you who haven’t yet, please consider filing a paid subscription; and whether or not you can do that, do please pass along word of the existence of our determined little enterprise to your friends. We shamble on!

* * *

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com. And do please subscribe and share!