August 4, 2022 : Issue #22

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This time out, another of our somewhat more slender summer issues, basically in two parts: To begin with, from the ARCHIVES, a piece about the remarkable Brazilian political-conceptual artist Cildo Mereiles’s bracing project at the Museum of Modern Art, from back in 1990, alas as salient today as it was back then. And then, a new winner in our CONVERGENCE CONTEST, as celebrated Mexican film director Alejandro Iñnáritu rhymes off of that short lyrical Herz Frank documentary about children watching a puppet show from a few issues back, and I in turn riff off his association with a few further rhymes of my own.

* * *

From the Archive:

Brazilian Artist Cildo Mereiles at MOMA, 1990

Art News, Summer 1990

Brazil, a principal focus of my 1990 book, A Miracle, A Universe: Settling Accounts with Torturers, has once again been percolating to the forefront of my thoughts in recent days. According to an item in the Washington Post of this past July 8, citing a dispatch from the Brazilian Space Agency, “Deforestation of the Amazon hit a new record during the first half of 2022, deepening concerns that the vast rainforest’s critical role in protecting the planet’s health will be irreparably damaged.” There have been the usual dismaying numbers of assassinations of local activists and environmentalists, three this past January (this again according to the Washington Post) “killed along a forested patch of the Xingu River that property records show had been claimed by the local mayor’s brother.” And of course there were those two intrepid researchers killed last month in the borderlands to the far west of the country, eliminated while completing research on a book tentatively to be titled How to Save the Amazon. All of that amidst the lead-up to October general elections which will be pitting the front-running onetime president, ex-labor-activist Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, against the neo-fascist incumbent (and fervent defender of the military regimes that had played such a baleful role in the events I had chronicled back in that 1988 book) Jair Bolsonaro, who, notwithstanding the fact that he has been consistently polling in the low thirties, has regularly been adamantly insisting, preemptively, that he will treat anything less than total victory as a “rigged” outcome, one that he has no intention of honoring.

All of which had me recollecting an article I filed with Art News back in 1990, around the time of the publication of that Miracle/Universe book, following a visit with the extraordinary Brazilian artist Cildo Mereiles as he was completing the installation of a piece over at the Museum of Modern Art, a piece (and an article) alas as pertinent as ever.

*

Just before the opening of Cildo Meireles’ recent installation at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Brazilian artist’s assistants were busy feeding the bones—which, in retrospect, seems entirely appropriate. Like peasants out of a Millet canvas, they were reaching deep into canisters, extracting fistfuls of grainlike pellets and flinging them across the field of dry white cow bones. It was a large field—hundreds, thousands of bones (“three and a half tons worth,” Meireles subsequently noted, “all of them transported up here from Brazil, in crates”), spread out in a dense, even mesh across a wide circular space that was in turn girdled by a low retaining wall fashioned entirely out of white candles.

“Sixty thousand,” Meireles offered, before I could even ask, as another of his assistants slotted in the last row of candles, like a peculiarly fanatic brick mason. “Two tons worth. And again, all of them shipped up from Brazil. There they cost me the equivalent of $3,000—here I would have had to pay almost $40,000.” From the midst of this surreal landscape, a bit off center, rose the piece’s central element, a steep, elegant tipi, wrapped in a thick pelt of colorful leaves—or, rather, on second glance, a thick pelt of money:

thousands and thousands of paper bills shingled one upon the next. “Pesos," Meireles said. "Cruzeiros, cruzados, U.S. dollars, Canadian dollars, centavos, australes—bills from Guatemala and Costa Rica and Colombia and Peru and Chile, 6,000 of them altogether, bills from every country in this hemisphere where Indians once predominated, although in the years since, for the most part, they've all been wiped out." Meireles calls his piece Olvido (Oblivion).

Actually, Meireles explained, this was his second crack at the same theme. A few years ago he'd been invited to submit a piece in commemoration of the 300th anniversary of the first missionary expeditions into the Brazilian hinterlands in the south. The piece he eventually installed in Sāo Paulo (it was also featured in last year's celebrated "Magiciens de la Terre" show at the Pompidou Center in Paris) consisted of a dense cloud of cow bones suspended from the ceiling (strikingly backlit so that the bones seemed to hover, hauntingly blond), with a single narrow shaft of ghost-white Communion wafers descending from the bone cloud down to a square field, which was spread over with 600,000 sparkling silver coins. That one he had titled How to Build Cathedrals.

And yet his attitude toward religion—and in particular the Catholicism of his native Brazil—is more complex than those two macabre pieces might initially suggest. In 1973, near the end of one of the most repressive periods of Brazil's military rule, he created an installation entitled The Sermon on the Mount: Let There Be Light, in which he assembled a large cubic mass of 126,000 matchboxes in the center of a room. The room's walls were lined with mirrors, above each of which he'd printed one of the Beatitudes. (To suggest at that moment in Brazilian history that the poor deserved to be considered anything other than merely wretched approached the height of sedition.) The floor was covered with sandpaper and miked, so that each step a visitor took into the space was amplified and sounded like a giant match being struck. The cache of matchboxes itself was protected around the clock by five sinister-looking gentlemen in dark glasses, actors decked out to look like the grimmest of security personnel.

The piece was so transparently incendiary that it couldn't be shown for several years.

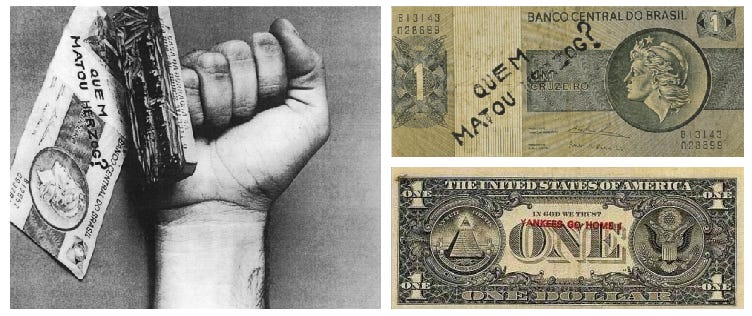

"There was a big problem with censorship when I was first getting started as an artist," Meireles now recalled. (He was born in Rio in 1948.) "By 1969 and 1970, for example, the regime was strictly monitoring all the standard means of communication—television, radio, newspapers, book publishing, galleries. So that in my earliest work I set myself the task of inventing alternative methods of communication—or rather, taking advantage of some of the alternate systems of circulation that already existed, Insertions into Ideological Circuits, as I called these exercises. Thus, for example, I began rubber-stamping political messages onto the faces of paper money that I happened to procure in the course of my day and which I then proceeded simply to spend. When in October of 1975, our beloved crusading journalist/playwright colleague, the Croatian-Jewish immigrant Vladimir Herzog, was suddenly snatched up by the military, terribly tortured, and then found dead in his cell, the supposed victim of a suicide by hanging, which nobody believed, I took to stamping ‘Who killed Herzog?’ across standard Cruizero banknotes. Or, whenever I happened to get my hands on an American dollar bill, I might stamp the message ‘Yankee go home!’ across its face, since it was well known that the Americans had been deeply involved in the military coup that overthrew our democracy back in 1964.

"In 1970 I figured out a way to silk-screen subversive messages with white paint onto the sides of empty Coke bottles, which I then returned for deposit. With those light-green, tinted Coke bottles, you see, the famous Coke logo was likewise emblazoned in white paint; it was very visible when the bottle was filled with the dark brown liquid but virtually invisible when the bottle was empty. In the same way, my message remained secret and invisible until the bottle was refilled and once again shipped out for sale."

Meireles reached into his satchel and pulled out a photograph of some of those simple Coke bottles. Quietly displayed in such a context, they seemed as tame and merely ironic as some of the other Dadaist gestures that artists about the world were indulging in around the same time (like Warhol’s soup cans); in the Brazilian context of that moment, however, they must truly have carried a wallop. One for example demanded, simply, ‘Free elections!’ Another appeared to diagram a method whereby that very bottle could be turned into a Molotov cocktail.

The catalogue also includes a photo of Meireles himself during that period looking quite lean and radical and surly—a Latin American Jean-Paul Belmondo. Today he's more well-rounded, paunchy (his well-worn plaid flannel shirt straining against his midriff in a way it probably didn't years ago when he first bought it), self-ironic, his black hair having gone to gray. His art is less overtly political. Or rather, his politics are more circumspect, less polemical, more steeped in a sense of the tragic dimensions of the issues he addresses.

In the piece at the Museum of Modern Art, for instance, the various components of the installation keep performing subtle symbolic inversions; the bones are organic elements, tokens of life, and yet they also read as death; the candles, tokens of devout Catholic practice, encircle the installation like a protecting levee but then again like a prison wall, their waxiness opaque and yet potent with the possibility of light and redemption. The money pelt surrounding the tipi at first looks organic (and even when you realize what it is, it still insists on presenting itself as liveliness incarnate, all those playful faces); yet, as money it stands in for all the forces of greed and rapaciousness that have doomed successive generations of Native Americans, and the shelter of the tipi is transmogrified into a strangulating shroud.

The interior of the tipi, for that matter (visible through a sashlike opening) turns out to be filled black with burnt-out charcoal—once-nurturing warmth run amok, furious holocaust guttered out to cold ember. (Both the charcoal inside and the paper money outside the tipi suggest disturbing transformations of the wood in the rapidly receding forest.)

Meireles has suffused the entire installation with an almost subliminal soundtrack, an eerie, initially indecipherable wheezing drone—the thrumming incantation of a gathering of native shamans, perhaps? The intrusion of distant motorbikes? A fusillade of machine-gun fire? Chainsaws nibbling away at the forest's edge? (In fact, admitted Meireles, it's the latter.) It was in this context that Meireles' assistants sowing their pellets fit in so perfectly; it turned out they'd been lavishing the bones with insecticide; a few stray cockroaches had apparently insinuated themselves amid the cow bones, so that the seeds Meireles' assistants were sowing were those of death.

"The problem of the extermination of Brazil's Indians," Meireles commented, "for they are in fact being exterminated as we speak, is not simply one of Indians versus whites. Rather, it's poor people being pitted against other poor people. In 1950, 70 percent of Brazilians lived in the countryside, with only 30 percent in the cities. The great majority of Brazilians subsisted by farming their meager plots. But over the years the big landholders swallowed up more and more of those plots, expelling the peasants, often at gunpoint, and converting their lands to monoculture—oranges, for example, or cattle, usually for export. This year we're doing a new census and we expect 85 percent of Brazilians will be seen to be living in the cities, the vast majority of those in truly wretched favelas. Some, however, instead move deeper and deeper into the hinterlands, out of desperation, where they of course begin encountering the Indians who've been living there for centuries. And soon you begin seeing these terrible massacres."

Meireles recounted how during the '40s and '50s his uncle Chico Meireles had ranged the jungle, a famous sertanista, an explorer who was specifically seeking out the Indians. "He felt that contact would be inevitable," Meireles said, "and he saw it as his function to reach the Indians first and explain to them what was about to happen, to try to get them to secure economic control of their own lands, even though such a notion was a perversion of everything they, and he, believed in.

"Chico's son, Apocna, managed to set up a national park, an Indian preserve, in Aripuana, but he had a terrible time trying to convince the normally migratory Indians to stay within its confines, not to cross those arbitrary, invisible borders. The chief would complain to him about how when the season came his grandfather always used to lead them over to that mountain over there, on the horizon, and now here my cousin was telling them they could no longer go—how could that be?

There are “terrible tensions on the edge of the jungle nowadays" Meireles continued, as he watched his assistants making the final adjustments on his installation, rearranging a few bones here, realigning a few candles there. "Several years ago I was visiting my cousin, deep in the jungles of Rondonia territory (it's since become a state), where he had an outpost near an Indian encampment. In the distance you could hear the chainsaws relentlessly clearing the jungle—closer by, you could hear the Indians, huddled in their anxious deliberations. And then suddenly you didn't hear them anymore. 'Oh no,' my cousin said, and he bolted out of the building and into the underbrush, with me in hot pursuit. We were running for a long time, but then we came upon a scene I'll never forget; a bunch of terrified Indians brandishing guns, pointing them at a little family of five blond-haired, equally terrified boia fria—white trash, the ones-who-eat-their-meals-cold, we call them. The Indians had already torched their hut, trashed their store of powdered milk. The babies were screaming, the mother clutching them, trembling. It was so pathetic—these poor wretched people at each other's throats. But that, these days, is the Brazilian reality."

* * *

CONVERGENCE CONTEST WINNER

Alejandro Iñárritu responds to Herz Frank

Followers of this Cabinet will perhaps recall the charming 1978 Herz Frank lyric documentary short Ten Minutes Older from a few issues back, which limned the real-time experience of a group of young children as they gazed, transfixed—by turns ensorcelled, terrified, and becalmed—upon the unfurling of a puppet show before them, here reprised:

Such followers might in turn recall how we followed that up with a dip into the Archives for my New Yorker talk piece about the Broadway jaunt upon which I accompanied Dario Fo and his wife Franca Rame one Sunday afternoon during the mid-Reagan administration—six plays in two hours!—and how, by way of postscript, I described the way that jaunt over the subsequent years had imbued in me the fantasy of a single-take Steadicam meander along the back alleys of the Broadway district, diving past back doors on through to offstage vantages of one rapt audience after the next, something along the lines of Russian Ark’s dreamy meander through the back halls of the Hermitage and all of Russian history. I noted how for that matter, the eminent Mexican director Alejandro Iñárritu had in fact accomplished something of the same effect in 2014 with Birdman, his Academy-Award-winning, single-take-seeming study of a Broadway actor (played by Michael Keaton) on the steadily compounding verge of a nervous breakdown; but I also registered my profound doubts as to whether any actual documentary along the lines I myself was envisioning could ever be realized, what with the compounding hackles the prospect would doubtless raise among intellectual property lawyers, union reps, producers, theater owners, and other such gimlet-eyed types.

So anyway, I was delighted a few days later to receive a note from Iñárritu himself, confirming my surmise that such a documentary would likely never be possible (the same sorts of forces, he indicated, had confounded and almost tanked his own fictional efforts on Birdman, which it occurred to me might help account for his own retreat the next time out to the relatively pastoral alternative fields of The Revenant, where by contrast all his hero Leonardo DiCaprio had had to contend with were the depredations of a humongously ravenous giant bear—a film which incidentally had netted Iñárritu himself a second consecutive directing Oscar, the first such back-to-back conjunction in over sixty-five years).

That obviously wasn’t the part that had delighted me. But the main thing Iñárritu had been writing about, he went on to explain, was his marvel over the Herz Frank Ten Minutes Older short, which he’d greatly esteemed and, surprisingly, never before encountered. It reminded him, he went on to say, of a four-minute short he himself had contributed to the 60th Venice Biennale, in 2007, as part of a 32-director anthological love letter to the big screen entitled “To Each his Own Cinema.” And indeed you can immediately make out the (unintended, unaware) rhyme with the earlier Herz Frank picture. Before I say anything else about Iñárritu’s short, Anna, though, do look at it for yourself, as I got to, because Iñárritu had graciously included a link (warning: spoilers ahead):

As you will have seen, it takes a while to make out what is going on, but we gradually come to realize that we are watching the play of light across a woman’s face, and more specifically the cast of cinema across the face of an utterly rapt moviegoer. The cinephiles among you will likely have identified the movie in question—the swell of that lushly tragic George Delarue musical theme, the woman’s male neighbor’s clipped depiction of the action—as Jean Luc Godard’s Contempt, and in so doing have realized that, apart from everything else, this brief short constitutes Iñárritu’s homage to that earlier master of the French New Wave. At the end, the overwhelmed moviegoer, having fled the darkness of the theater into the bright benighted light outside, leans into the embrace of the man who has now joined her and asks, “Was the film black and white?” (for by now we will have come to understand that she herself is blind). But of course the cinephiles among you will also have realized how hers is a key question, because Contempt in 1963 was Godard’s first foray beyond the black and white of his earlier films (Breathless, A Woman is A Woman, My Life to Live, and so forth) into color, and not just color but the ravishing technicolor demanded of him by his first high-end American producer, which he in turn wields to utterly besotted effect.

I happened to be visiting my dear old pal Mort in Bozeman the other day and showed him Iñárritu’s haunting short on my laptop. (I should note here that I’d asked Iñárritu if he would mind my sharing the film with others and he’d responded, “Of course you can use it as you want. As Godard wrote me in a fax at that time I asked him if I could use the superb music from his film: ‘The only right an artist has is to give over his art.’” A glorious sentiment which I may appropriate as the motto behind this entire Wondercabinet project.) I was trying to describe the dazzling color in the Contempt scene in question and was surprised when I couldn’t just pull the thing up on Google. It turned out that Mort subscribes to The Criterion Channel, though, so we were able to watch the whole movie on his crisp wide plasma screen, culminating in the scene which had held the blind moviegoer in Iñárritu’s tribute so transfixed, part of which I recorded on my iPhone and you can see it here: Michel Piccoli, in his first significant role, and Brigitte Bardot in the wrenching process of breaking up as they descend the precipitous steps from Curzio Malaparte’s storied clifftop villa on the isle of Capri toward the devastatingly blue sea below. Great movie, amazing scene (marvelous screening service).

And the vividness of the color only returned one to the principal wallop of Iñárritu’s conceit: The aching depths, the throbbing resonance of his moviegoer’s stilled gaze. I said as much to Mort, and he asked if I’d ever seen another short, a favorite of his, Cameron Burnett’s precociously early effort from 2016, The Bench. I hadn’t, so he now pulled it up on his laptop (this was turning into my kind of day), and here it is:

Indeed, another penetrating take on the abiding complexities of the blind gaze. I couldn’t help but notice, too, in the closing credits how Cameron’s short in turn was based on a screenplay by another young Mexican director, Alonso Alvarez Barreda. What was it with these Mexicans and blindness?

The very question jarred loose another long-buried association of mine, the memory of a story my dear late New Yorker colleague Alastair Reid once told me about a story that Jorge Luis Borges, the great (alright) Argentinian (but still) ficcionario once told him. For a long while, Reid was one of Borges’s principal English language translators. And Borges, notwithstanding the vividness of his writing, both prose and poetry, was virtually stone cold blind, notwithstanding which he was also the director of Argentina’s National Library from 1955 through 1973. Every day, he once told Alastair, he would descend the beaux art library’s magisterial steps and broad sidewalk to the curb of the busy wide boulevard below and then wait there patiently curbside, his white cane in hand, till some kind passerby would take his arm and escort him across the bustling thoroughfare to the taxistand on the far side (from which the drivers would eagerly vie for his trade, never accepting fares from the great man). One day, as usual, Borges related, a kind stranger grabbed his arm and the two proceeded across the surging avenue, on the far side of which the stranger let go of Borges’s arm and thanked him profusely: “It’s so unusual nowadays,” the man said, “for a stranger like you to escort a blind man like me across a street the way you just have.” And, ah, the look that spread across Alastair’s sly face as he savored the memory of the look on Borges’s face as he came to the end of that little tale!

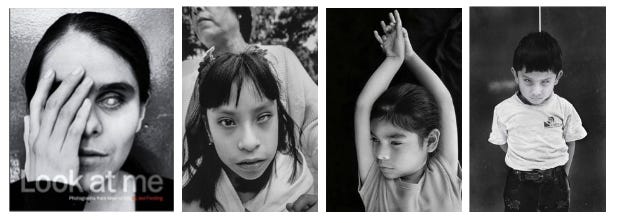

So there was that association, but then too another to Chicago photographer Jed Fielding’s astonishing volume Look at Me: Photographs from Mexico City (so there: back to Mexico proper again!) which turned out to center, now that I remembered it, around a series of searing, penetrating portraits of children at a school for the blind—though hardly pictures of pathetic disability, rather images of lives in the vivid fullness of their liveliness and of blind subjects looking back. Some instances pulled from the web:

Of course, Fielding is hardly the first photographer to have trained his lens on the face of blindness. Indeed, a person could fill a whole posting of reflections on such instances (Paul Strand, Lewis Hine, Garry Winogrand, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, André Kertész, and on and on), and I was getting all set to do so myself, right here, right now—except that, what would be the point? Geoff Dyer, as is so often the case, has already beat us all to the party here, with twenty pages of such observations near the outset of his kaleidoscopic thought-suite on our photographic heritance, The Ongoing Moment, each insight somehow more trenchant than the one before (“The blind subject is the objective corollary of the photographer’s longed for invisibility”) and the lot of them tumbling forth, one upon the next, like nothing so much as a sequence of the sort of jazz improvisations Dyer himself is so fond of riffing off of in other contexts. Best, as ever, to just check him out for yourself.

On the other hand, while combing the web for samples of Fielding’s work in that register (the best site naturally turning out to be his own, here), I also happened upon this pair of video clips pitched from the vantage that I don’t believe (I can never be sure) Dyer has yet surveyed, the first an AP report on a Mexico City photography class for blind students, and the second, somehow even more affecting, a short profile of Teco Barbero, a blind Brazilian reporter and photographic journalist in action in the field (Sao Paulo, as it happens, which of course brings us back to the very start of this posting). The technique Barbero uses, first palpitating the face of the stranger he intends to frame, often results in an especially fresh vantage: the looks he gets back! The exchange of gazes: the taut reverb of intersubjectivity.

But, as usual, I digress.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

Animal Mitchell website.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Bouncing off the end of this one (that exchange of gazes, the reverb of intersubjectivity) with an added ricochet off of Blaise Agüera y Arcas’s thoughts a few issues back on the social matrix necessary for theory of mind, a bit of an experiment on The Rise (and occasional fall) of Primate Theory of Mind across a series of videos. More summer fun!

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com. And do please subscribe and share!