WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Welcome to our thirtieth issue, starting out with a quick solar cappuccino and then proceeding, by way of celebration, to not one but two Main Events, the first an uncanny Hockney-Aboriginal convergence, followed by the last of our series of Footnotes From a Book You Don’t Have to Have Read or Ever Read. But now you could, since at long last it’s finally been published! So do please peruse details on that development and another important announcement on the wider State of the Cabinet at the bottom of this issue.

***

For Starters

A Cappuccino-Solar convergence

Walter Murch photo of a cup of cappuccino he was served in Rome, and NASA solar telescopic photo of the sun, from around the same time. Regarding which, more discussion in the weeks to come.

* * *

Main Event #1

A Hockney-Aboriginal convergence

A few weeks ago, I happened upon a paragraph by the redoubtable if ever so elegant Justin E.H. Smith from an essay of his on “Walking, Seeing and Thinking” in the November 6, 2022 issue of his Hinternet Substack (one of my own very favorite such sibling publications). To wit:

We know that a huge amount of our neural bandwidth is taken up by spatial orientation and other elements of navigational cognition. It is worth mentioning here that cognitive scientists have studied the hippocampi of London taxi-drivers with mastery of what is locally called “The Knowledge,” as exemplary of what a human mind does at its most excellent. It is also worth noting that in many non-western contexts, this same cognitive ability that the cabbies display may be experienced as a sort of identity between the mind and its environment. Thus Australian Aboriginal “songlines” are at the same time both embedded in the geography of the continent in the form of natural features, and in the mind as vast bodies of memorized song. But where then is the songline exactly—in the world or in the head? Is it a going or is it a thinking? It seems that this question would make no sense from the point of view of anyone who may be said truly to know the songs.

That passage in turn reminded me of an orphaned essay of my own—orphaned in that it had been slated to be the next entry in a series of “Pillows of Air: Monthly Ambles through the Visual World” which I’d been offering by way of The Believer magazine for a while in the 2013-4 period but which had had to be suspended when the good folks there ran into a bit of a financial squeeze. In my mind, I was convinced that it had run there, but apparently not, and I began to doubt that I’d ever actually even written the thing up (was it in the world or in my head?). I ended up having to dig deep back through several generations of retired laptop hard drives before I was indeed able to pluck it back up. But anyway, here it is:

So, what are we to make of this? Two big long paintings, almost exactly the same size, created on virtually the opposite ends of the earth by artists who would likely have had no reason to know of each other, and yet that look and feel uncannily alike.

*

The first is by David Hockney, from 1980, (218 × 617cm), portraying, in the words of its title: Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio (1980).

In all kinds of ways, this painting signaled for Hockney a breakout from the prior decade’s remarkably successful focus on hyper-stilled portraiture, often of two people at the same time, contained in the rigid vise of one-point perspective (think of such iconic pairings as Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Their Cat Percy, or Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy). Hockney’s dealers and his fans would likely have been perfectly content to see him going on doing those kinds of things for years. But he was growing increasingly restless, both with the stillness of the subject matter and with the constraints of photo-based perspective (photography being alright, as he never tired of saying, if you didn’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralyzed Cyclops, for a split second).

The first thing to notice about Mulholland Drive is its scale, perhaps influenced by the series of opera stagings that Hockney had been undertaking in the years immediately prior to its creation; and the second thing might be the explosively celebratory and vivid panache of its palette, likewise, no doubt, thus influenced (though Hockney liked to insist that, no, those were just the colors of Southern California). But the main thing to notice is its dynamism, how unstill it is. Indeed, in Hockney’s Mulholland Drive, “drive” is a verb. In this context perhaps influenced by the enormous impact of the scroll paintings he’d encountered on a trip to China the year before (and the surge of reading on Chinese art which that encounter had precipitated), with this painting Hockney revels in a moving focus: your eye goes for a ride, and with each bend in the road, you are given a fresh new vantage: those powerlines, the tennis courts, that pool, and over on the other (far) side of the crest, the vast expanse of the San Fernando Valley with its endlessly receding grid of avenues and cross-streets, rising into the skies. (Notice how the dip and swirl of the crestline boulevard on the left side of the painting punningly evokes the entirety of the Los Angeles peninsula as it juts into the sea.) This painting is Hockney’s ebullient homage to a city that, with each new canvas, the British transplant was ever more definitively making his own.

Okay, fine. But what to make of that other one? A painting with almost exactly the same dimensions (195.0 x 610.0 cm), virtually an identical palette and much the same form, which I happened upon several years back almost half way around the world, at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia. This one, titled Dulka Warngiid, was, according to its wall legend, the product of a 2007 collaboration among seven aboriginal artists, the greater part of whom had had virtually no intercourse with world artistic trends up to that time: Sally Gabori, May Moodoonuthi, Dawn Naranatjil, Netta Loogatha, Amy Loogatha, Ethel Thomas, and Paula Paul. And there they all are, standing in front of their masterpiece with justifiable pride.

The painters were all members of the Kaiadilt people, the traditional owners of Bentinck Island, the largest of the South Wellesley chain at the bottom of the Gulf of Carpenteria in Northwest Queensland, Australia, and though their lives had flung them all about Australia, they returned in 2007 to an arts and crafts center on nearby Mornington Island at the behest of Sally Gabori, their contemporary and fellow Bentinck Islander, who had already been painting there, quite successfully, for a couple years (that’s her, second from the right); the rest had never painted before. The title of the epic canvas they now set about creating, Dulka Warngiid, is, as with many aboriginal phrases, a bit hard to translate: “Dulka” I’m told, can mean “place,” “earth,” “ground,” “country” or “land”; and “Warngiid” can mean “one,” but also “the same,” “common,” “in common,” and “only.” So it can be translated “Land of All.” But the main point here is that since that narrow island was for most of the elder artists’s youths the only place they knew, a more accurate rendition of the title might be “The Whole World.”

And indeed the canvas itself plays out the essence of indigenous Aboriginal social organization, which according to the Australian linguist and anthropologist Nicholas D. Evans (writing in The Heart of Everything: The Art and Artists of Mornington & Bentinck Islands), “is to give each person a clear, individual, and inalienable local identity which ties them to their particular country in spirit, feeling, knowledge, art, and jurisdiction, but then to integrate all these small parcels into an overarching, interdependent whole.” Each of the women thus took on a section of the canvas, summoning up associations to her particular corner of her heart’s true home there on the island. Evans goes on to note how “the potentially centrifugal jarrings of their radically varied techniques” got harmonized in the canvas to a remarkable visual unity, aided in part by “a common iconic rhythm whose periodicities recur across the canvas through [representations of] casuarina seeds, chunks of ochre conglomerated into mudstone, rocks placed along a fish-wall, sand-wells dug along a beach, and the holes made by the stippled wakes of fish in a school.” He goes on to invoke their word “dirrbatha” to describe “the way they line up shells in geometrical patterns in the ashes for cooking,” furthermore noting how “the beating of motifs here evokes the care they show as mothers and grandmothers in creating the patterns of their pre-dusk campfires.”

All of which is to say that with Dulka Warngiid, Sally Gabori and her sister Kaiadlit elders are doing pretty much exactly the same thing that Hockney was doing with Mulholland Drive: giving a soaring sense of the lay of the land and the deep rhythms of the heart.

Alright. But what to make of this?

On the left, of course, Mark Rothko, Untitled Red on Crimson (1969) and you won’t be surprised to hear that it was one of the first things I thought of, a few minutes after viewing Dulka Warngiid, when, rounding the corner there at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, I came upon the painting on the right, another iconic Aboriginal masterwork, this one by Long Tom Tjapanangka (circa 1930-2006) of the Pintupi people of Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Tjapanangka, as I was subsequently able to learn, spent most of his life wandering the continent as a stockman and a police tracker, memorializing the places he’d seen on his farflung travels when he started painting in 1993.

Of the abstract expressionists, Rothko was always among the more spiritually pitched (not for him the mere brute facticity of paint on canvas). “The people who weep before my paintings are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them,” he once said, going on for good measure to insist that “If you are moved by the color relationships, then you miss the point.” And I have seen this particular canvas of Rothko’s likened to the Burning Bush or the Tablets Moses brought down from the mountaintop. From out of the bruised insubstantial mist, it can get to be as if the Face of God Himself emerges to interrogate the viewer, Infinite Thou to the viewer’s Infinitessimal I. And it does bore in on one.

Long Tom, for his part, preferred (somewhat unusually for Aboriginal artists) to paint the world before him, the literal actual world, or at any rate the one deep-etched in his own walkabout memory. This particular canvas is entitled Uluru and Tarrawarra (1994), invoking the indigenous names of two of the most sacred sites in the Aboriginal cosmos, Ayers Rock and the Olgas.

And there they both are, rock solid, stacked one atop the other.

Uncanny, thus, the way in which both Rothko and Long Tom reference the transcendental, from radically opposite vantages (the spiritual and the literal-minded).

Of course, I was hardly the first to have sensed the Rothko/Long Tom rhyme there at the Gallery in Melbourne. Talking about the experience a bit later with one of the curators, she related how late in his life, somebody showed Long Tom a book of Rothko paintings, to which the wry Aboriginal, unfazed, responded, “Huhn, that guy paints just like me.”

* * *

Main Event #2

A FINAL FOOTNOTE FROM A BOOK YOU DON’T HAVE TO HAVE READ OR EVER READ AND FOR THAT MATTER COULDN’T HAVE YET IN ANY CASE BECAUSE IT HADN’T EVEN APPEARED UNTIL NOW

“Final” because, as veteran Wondercabineteers may have noted, I have long been salting this Substack with Footnotes from a soon-to-be-released book (of my own, I can now confess), though said release kept seeming to get postponed from one season to the next. (See issues 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7. 9, 10, 12, and 21 for earlier instances from the series.) Good luck to anyone trying to figure out what sort of text could possibly have held the wildly heterodox and digressive progression together, but it can now be revealed and will be in the afternote to this, the final such offering, and the final footnote, as it happens, in the book: a footnote, perhaps inevitably, on the history of footnotes (or so it starts, at any rate). To wit:

FOOTNOTE 39

And maybe here, in closing, is the time to hazard a moment’s thought on the phenomenology of footnotes themselves. I once read somewhere how Freud, for his part, once asserted that footnotes serve the scholar as a way of signaling the presence of something large and pendulous down under.

But could that be right? Not whether the assertion is true (an entirely separate question, which we might as well bracket for our purposes here) but rather whether my memory may simply be deceiving me (in a classically Freudian manner) with that possibly phantom recollection? Naturally, in order to try to settle the matter, I had recourse to the web, but the problem when you type “Freud” and “footnote” and “pendulous” into Google is that it turns out that some guy has actually compiled a scholarly study entitled Freud’s Footnotes (naturally, of course: some scholar would have had to have gotten around to doing that), such that the first several pages of links turn out to exclusively reference that essential manual—usually with the word “pendulous” simply crossed out.

So no luck there. But then I remembered how years ago I’d savored a truly seminal volume on the history of footnotes themselves, my friend the Princeton historian Anthony Grafton’s magisterial treatise, The Footnote: A Curious History—could that be, I wondered, where I’d first come upon the anecdote? So I grabbed that volume off my alphabetically arrayed shelf (“It’s not hoarding if it’s books,” I kept intoning my reassuring mantra), tore through to its index and drilled for “Freud,” only to discover that, surprisingly, there was no such listing at all. Hmmm. But the sheer heft of the thing in my hands brought back such enchanted memories that I turned back to the book’s preface, where in his very first paragraph Grafton observes:

Many books offer footnotes to history: they tell marginal stories, reconstruct minor battles, or describe curious individuals. So far as I know, however, no one has dedicated a book to the history of the footnotes that actually appear in the margins of modern historical works. Yet footnotes matter to historians. They are the humanist’s rough equivalent of the scientist’s report on data: they offer the empirical support for stories told and arguments presented. Without them, historical theses can be admired or resented, but they cannot be verified or disproved. As a basic professional and intellectual practice, they deserve the same sort of scrutiny that laboratory notebooks and scientific articles have long received from historians of science.

And so forth. I cut ahead to the first chapter, “Footnotes: The Origin of the Species,” where Grafton launches out, “In the eighteenth century, the historical footnote was a high form of literary art.” Whereupon he proceeds to celebrate those of Edward Gibbon, author of course of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the delicious “irreverence” of whose footnotes went far “to amuse his friends and enrage his enemies.” A characterization which elicits Grafton’s own footnote number 1, already packed with detailed confirmatory citations. Grafton then goes on to sample some of his own favorite sly Gibbonories, such as:

“The duty of an historian,” remarks Gibbon in his ostensibly earnest inquiry into the miracles of the primitive church, “does not call upon him to interpose his private judgment in this nice and important controversy.”

(or)

“The learned Origen” and a few others, so Gibbon explains in his analysis of the ability of the early Christians to remain chaste, “judged it the most prudent to disarm the predator.” Only the footnote makes it clear that the theologian had avoided temptation by the drastic means of castrating himself—and reveals how Gibbon viewed this operation: “As it was his general practice to allegorize scripture, it seems unfortunate that, in this instance only, he should have adopted the literal sense.”

A few pages further on, still anatomizing the special appeal of Gibbon, Grafton opines as to how,

Though his footnotes were not yet Romantic, they had all the romance high style can provide. Their “instructive abundance” attracted the praise of the brilliant nineteenth-century classical scholar Jacob Bernays, as well as that of his brother, the Germanist Michael Bernays, whose pioneering essay on the history of the footnote still affords more information and insights than most of its competitors.

That being the end of a paragraph, just four pages into the chapter, to which Grafton already appends footnote number 14. A footnote whose own slyly lilting erudition mirrors that of Grafton’s hero, to wit:

The phrase “lehrreiche Fulle” is Jacob Bernays’, as quoted with approval by his brother Michael Bernays. The relationship between the two brothers deserves a study. Jacob mourned his brother as dead when he converted to Christianity, but Michael nonetheless emulated Jacob’s analysis of the manuscript tradition of Lucretius in his own genealogical treatment of the editions of Goethe. {Whereupon Grafton interposes five detailed lines of specific amplificatory citations, before concluding} So far as I know, the third brother, Freud’s father-in-law Berman, did not venture any opinion on Gibbon’s footnotes.

That last sentence threw me for a bit of a loop, or actually two loops. Because, first of all, I thought, Wait a second, why wasn’t that “Freud” reference included in the book’s index, and did that in turn mean that the Freud-pendulous anecdote might in turn still lie hidden somewhere else in Grafton’s volume? But more to the point, I knew all about Berman Bernays by way of his granddaughter, Judith Bernays (Heller), a close friend of my own grandmother Lilly Toch (and indeed her housemate for several years after the death of her husband, my grandfather the composer Ernst Toch). Judith, for her part, never tired of explaining to us how she was “twice the niece of Freud.” Which is to say that Freud and his sister had married a brother and sister, such that Judith was the daughter of Sigmund Freud’s sister Anna and Freud’s wife Martha Bernays’ brother Eli. (For good measure it is now thought highly probable that in the years leading up to 1900, the year he published The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud was having an affair with the youngest sister of Anna and Eli, Minna, who may consequently have needed an abortion, which in turn explains why Freud may have had to go to Rome, a trip much referenced in the book. Minna for her part went on to live as a spinster with the Freud family for decades thereafter—but that too is a whole other story. For more on which, though, see the piece on Peter Swales and his research in the New York Times of November 22, 1981.)

Judith’s own kid brother, as some of you may already have surmised, was Edward Bernays, the notoriously famous founder, in the years after the First World War, of the entire corporate focus-group-convening, consumer-taste-molding, public-opinion-swaying public relations industry in the United States, or so anyway he liked to fancy himself—and many, including Adam Curtis in his BBC documentary series The Century of the Self, have seemed to concur. I myself came to realize this when, at Judith’s behest, I would occasionally pay calls on Edward in his elegantly burnished Lowell Street, Cambridge manse, and he would entertain me with tales of how, among other triumphs, he had virtually singlehandedly convinced Americans (at the behest of the pork industry) that bacon was a virtual breakfast essential (oy!); that cigarettes granted “torches of freedom” to young women of the 1920s who’d never much fancied tobacco; and that in the wake of Prohibition, beer (as opposed to hard drinks) constituted the essence of moderation and even provided “a vaccination against intemperance.” He was known as “the father of spin,” would come to be crowned one of Life magazine’s “100 Most Influential Americans of the Twentieth Century,” and, from what I could tell, through the end of his days was altogether satisfied with his capacious good works.

Judith, on the other hand, was made of grimmer stuff. She brooked no guff, or so it seemed to me and my siblings during our younger years when on visits to our grandmother’s, perhaps in all fairness, we gave her nothing but. She was a dark and brooding presence, short and stooped and shuffling, and the spitting image of her uncle, with the same hard-set battle-ax jaw covered over with the same fine pelt of blanched whiskers, before which we kids used to marvel in stupefaction. But over the years she grew on me, or maybe I just grew up. (“When I was a boy of fourteen, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be twenty-one, I was astonished at how much he had learned in just seven years.”—Mark Twain). By the time I was twenty-one, I was deep into college at Santa Cruz, and what with the passing of my grandmother back in Santa Monica, Judith had returned to her prior abode in Berkeley, so I would go up to visit with her every few weeks. I used to revel in her tales of her visits back to Vienna and her stays with the Freud family, and then her years in London when she gravitated around the Bloomsbury circle, contributing translations to the Hogarth Press’s twenty-four-volume edition of the complete works of Freud,

and I used to regale her in turn with my own growing conviction that, his avowed and flinty skepticism notwithstanding, her uncle (subject of my junior thesis) had been, perhaps even unbeknownst to himself, some sort of latter-day secular Kabbalist (see my prior footnote along these lines). Judith was neither convinced nor, I suspect, remotely amused.

I spent the summer of 1973 in Berkeley in a somewhat hapless attempt at a crash German language course—hapless in part because I’m just not that gifted in languages; and especially so because I still suffered from something of an aversion to German in particular since it was the language that my parents, who basically got along fine, would revert to whenever they took to arguing, under the mistaken impression that we kids couldn’t tell they were bickering because they were doing so in a language we couldn’t understand but therefore grew positively to cringe at; but mainly because that was the summer of the Watergate hearings, and like everyone else, we would-be German-immersers instead spent the entire day glued to our TV sets taking the live telecasts all in, and then most of the evening watching the rebroadcasts of the same hearings all over again, aping all the best lines and mimicking the sputtering furrowings of Senator Erwin’s fantastically expressive eyebrows.

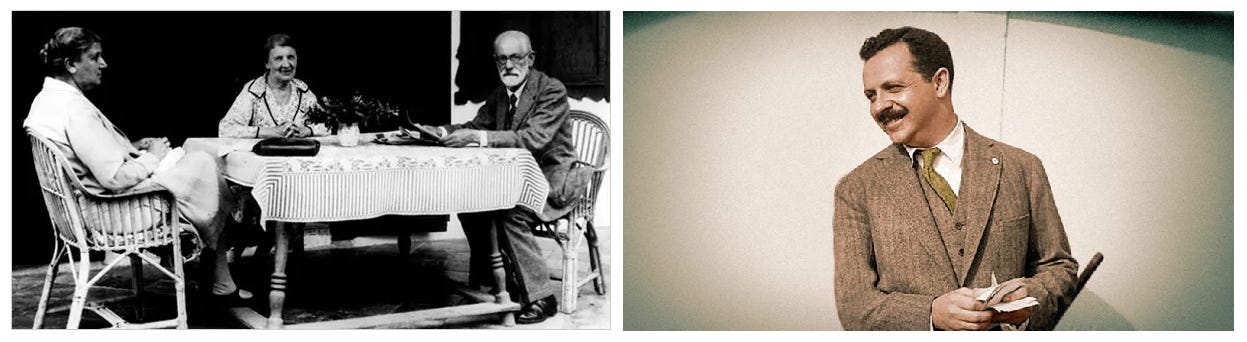

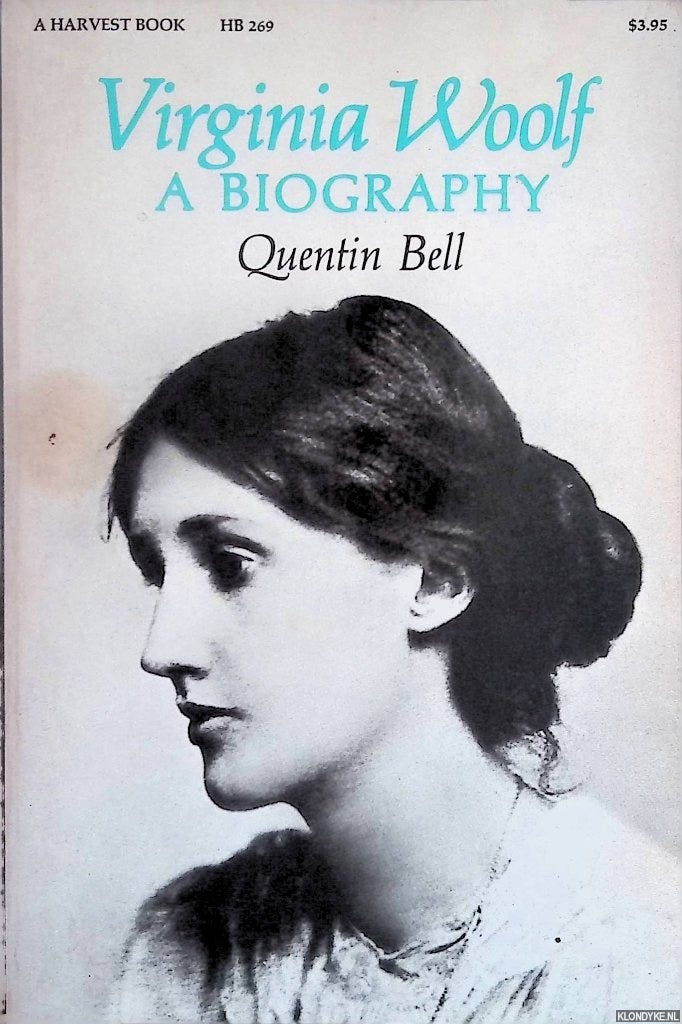

But every few days, during hearing recesses, I’d head over to Judith’s. She was quite frail by then and had gone completely blind, and so we agreed that I would read to her, and she wanted to sample the then-new Quentin Bell biography of Virginia Woolf,

one of the first of what would soon become a flood of such literary pathographies. As rapidly became clear, Bell’s take on things was quite salacious, and as I continued reading, I often glanced ahead with considerable trepidation at what scurrilous horrors lay just up the facing page. I needn’t have worried. One day, I gazed ahead and gulped at the upcoming prospect of a thoroughly lurid account of some of Lytton Strachey’s extracurricular activities, but I steadied my voice and just kept on reading. No sooner had we forded the passage in question than Judith interrupted me, grousing, “Nonsense: Lytton didn’t care for that boy one fig: who he really had the hots for that year was a randy Romanian sailor!”

Those were some of my last visits with Judith. In September I returned to Santa Cruz, where one day I received a manila envelope in the mail, addressed in oversize shivery letters. Judith was sending me the family’s print of the famous photo of Freud that graces the cover of Ernest Jones’ biography of him.

“This is my uncle,” she wrote in a note in that same shivery hand, “during his last year, in London, reviewing the page proofs for his last book, Moses and Monotheism. And this is just to reiterate to you that my uncle was no mystic. Nonetheless: love, Judith.” And she herself passed a few weeks after that.

Anyway, where was I? Oh yeah—whether or not Judith’s uncle ever actually said that thing about footnotes. I was coming up dry in my further investigations, but I was not entirely without recourse. So I picked up the phone and called Tony Grafton and outlined the entire situation, recounted some of my tales about Judith, complimented him on his footnote book though complaining about the evident inadequacies of its index, and finally just sprang the question point blank: had he, as perhaps the world’s leading authority on footnotes, himself included that comment of Freud’s about the large pendulous down under anywhere in his book or for that matter ever heard tell of it at all?

Grafton laughed and confessed that no, he hadn’t included the anecdote in his book and for that matter had never before now heard of it, but it sure sounded like Freud to him, and even if Freud hadn’t actually said it, he surely should have, and even if he didn’t that he, Grafton, wouldn’t be the one to call out the footnote police on me if I decided to include it.

So: who knows?

All I know is that somewhere there just has to be an end to all these digressions, and it might as well be here.

*

Actually, that didn’t prove the very last word, there was a tiny squib more, but to find out what that was, you will need to look into the book itself, which now at long last (following all manner of supply chain and editorial-perfectionist issues) you finally can. Because my latest book A Trove of Zohars, the fourth entry in my “Chronicles of Slippage” series, is finally available from Hat & Beard Press in LA.

What Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder did for the history of museums and wonder, and Boggs did for money and value, and Waves Passing in the Night did for the sociology of science, I hope that A Trove of Zohars will be doing for the early history of photography and the long heritance of Judaism.

The title spread may give you some idea of to what the book is up:

Some of you (though I doubt many) may recognize the novella-length first section as a recasting of the afterword to Predicting the Past, the one-hundred-dollar catalog to a recent show of Mr Zohar’s work, as curated by Mr. Berkman. But that 13,500-word shaggy-photographer chase of a narrative (an abridged version of which appeared a while back in The Atlantic online) has now been supplemented with 25,000 words of, as I say, wildly digressive footnotes, which taken together, among other things, may constitute the closest I am ever going to come to writing a memoir.

Anyway, as I say, the lusciously illustrated volume is now available, and you can read more about it here, and procure The Trove at a 20% discount at the publisher’s online store by applying the code “TROVE 20” at checkout here. Just in time for Christmas!

I mean, Hannukah.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

For more on the beard side of this Mustache-Beard convergence, see here.

The Animal Mitchell archive .

***

GETTING BY WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM OUR FRIENDS

Speaking of year-end occasions and the giving spirit

—I know, David, I know, give me a second, I’m getting there—this thirtieth issue, coming out as it does on this very day of thanksgiving, might offer a good moment for recalling the general philosophy behind this entire enterprise, and the wager that undergirds it. For from the start, my wingman David and I agreed that we would not engage in any sort of tiered distribution of the wonders on offer from this Cabinet (a little bit for everyone and progressively more for those who could afford to pay more). We wanted everything to be available to everyone, and (when necessary) for free—that aspiration was core to the DNA of the project from Day One. On the other hand, we intended to make it clear—and we have, though perhaps not as often as we should have—that writing (and editing) are work, honest and at times hard work, as deserving of compensation to the extent possible as any other sort of labor. And our wager was that enough of our subscribers would agree with that premise and chip in to the extent that they could to make the thing a going concern.

We’ve been gratified, to an extent, with the results. Our subscription base has been steadily expanding, and many of you have indeed been contributing financially to the cause. Though frankly not yet enough to assure our longterm survival (we have steadfastly avoided calculating how much we are actually clearing per hour of work—the total would likely, apart from anything else, just be too embarrassing). Still, we love the work, we’re proud of the project’s arc so far, and we are very eager to continue.

So it’s in that spirit that we turn to you. To those of you who have committed to paid subscriptions, thank you thank you thank you. (I know, David, I just did—David does, too.) To those of you who haven’t yet subscribed at our annual (non-inflation-adjusted!) rate of $60/yr or $6/mo, please do consider doing so. Those of you who can’t afford that amount—and we realize that times are tough for many—don’t leave! Everyone will always be welcome (see the Prime Directive above). Some of you have indicated that while you can’t afford the full fare, you’d like to be able to contribute occasionally, at a lower rate when and as you can—and we hear you. We will be endeavoring in the months ahead to set up some sort of tip jar (it’s not as easy as you might think) for such occasional contributions. Others, on the other hand, might be able to contribute more, in part to help cover the fares of those who can’t, and that too would of course be most appreciated.

Meanwhile, all of you can contribute simply by helping us to expand our base and reach! Do please share the Cabinet with friends you think might enjoy it (it’s simple, just hit the button below).

From the start the Wondercabinet has been a work in progress, and we will be continuing to evolve in the months ahead. Some of you have been complaining at the sheer heft of some of the recent offerings, and we hear you there, too. We intend to start experimenting with shorter main issues and perhaps occasional, yet-shorter mailings interspersed between the fortnightly broadsides. We have other schemes brewing as well: Just you wait and see! As ever, we welcome your comments and suggestions. And we cherish the privilege of your ongoing attention.

Your Tribe of Zohars sounds like a Taschen. Good style, if that proves true. 1 contribution in print to the idea that everybody is an artist was Douglas Coupland simply pro nouncing that idea after hearing that his niece was compositing voice and photos for a documentary for high school. Right. 2 it seems your enthusiasm for twin ideas will not let us down. Since 2014, I believe one of the most shared essays has been Graeber and t other David's Dawn of Everything book. Sure it is in the 400 ooo copies...monumental architecture is its second emphasis for argument that people are not made for 1984. Because shared monuments can represent live disagreements and more than interregneums peaceful you name it productivity demos or etcetera as Henry Miller would have it. Etc.

As a law student at Georgetown, the most entertaining article I edited for the Law Journal was all about the asterisk footnote.

You can see it here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=711083