WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This time out, a visit with my grandfather, the eminent Weimer-era modernist emigre composer Ernst Toch: not entirely forgotten, in fact just maybe even increasingly well-remembered.

* * *

The Main Event

Two dachshunds meet on the Palisade in Santa Monica—or so goes the story with which the European émigrés in flight from the fascist gyre engulfing their homelands used regularly to regale themselves on balmy evenings there along the arcing bay, back during the thirties and forties of the last century—and the one says to the other, “Here, it’s true, I’m a dachshund, but back in the old country, I was a St. Bernard!”

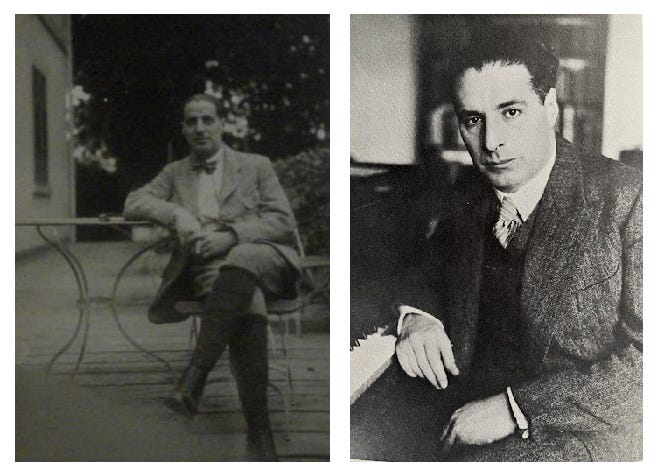

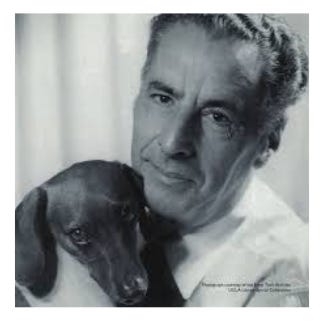

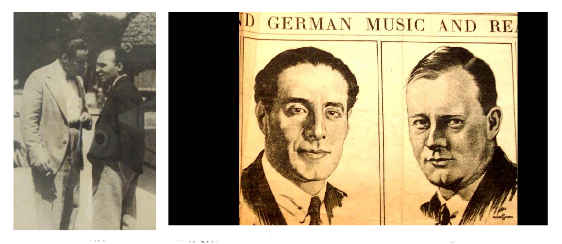

When it comes to my own grandfather, the Viennese born Weimar-era composer Ernst Toch, the jest always struck me as particularly bittersweet. In part because he’d owned a succession of dachshunds himself (each called Peter, and each somehow more cherished than the one before). But mainly because back in the Old Country, Toch really had been a St. Bernard: one of the principal stars of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, alongside Paul Hindemith (with whom he’d shared a major NY Times spread on the latest modernist trends in German music in 1930); an avid participant in all sorts of experimental festivals (including by way of his invention of The Geographical Fugue for spoken chorus, “perhaps the world’s first instance of rap music,” as his friend Nicolas Slonimsky used to say); the model for the profession of “Composer” in the photographer August Sander’s legendary survey People of the Twentieth Century, and not surprisingly so, since his dozens of chamber, orchestral and operatic pieces were regularly getting programmed and performed across the twenties and early thirties by the likes of Furtwängler and Klemperer and Steinberg and Emanuel Feuermann and Walter Gieseking (who performed Toch’s First Piano Concerto dozens of times all over Europe before Hitler’s ascension to power, following which, alas, he immediately pulled it from his repertoire, summarily cancelling an impending performance in London).

Poor guy, my grandfather Toch: not just because his forced flight from Berlin in 1933 (and eventual resettlement in Southern California) saw the end of that stellar reputation (notwithstanding his continued productivity through the end of his life in 1964)—but doubly so in that further down the line, following the death of his widow, my grandmother Lilly, in 1972, he got stuck with me as his musical executor, a role for which I was spectacularly ill-suited, not being the slightest bit musical, and worse. Indeed my astonishing amusicality, particularly given the positive surfeit of musical inheritance flowing into my personal genome (not only had my mother’s father been this astonishing prodigy but my father’s mother had been the head of the Vienna Conservatory of Music’s piano department and a concert soloist herself), the fact that I literally cannot hear whether any given sequence of notes is going up or down, used to so confuddle my longtime neurologist pal Oliver Sacks that he devoted a full page to the scandal in his book Musicophilia.

A few years before her passing, however, Lilly had thrown herself into a crash program to bring me up to speed on my specifically Tochian legacy (and it was a fascinating story and a remarkable trove), such that in the wake of her passing (when I’d just turned twenty), I threw myself into the project of mounting a citywide festival of Toch’s music, centered around his then-new Archive at UCLA, to honor the tenth year since his passing. As part of that, I compiled a biographical essay for the brochure that got distributed at each of the twenty-odd events, which actually, now that I look back upon it, was my first published (albeit sort of self-published) text.

The amazing thing is that in the meantime, and really (honestly) not particularly owing to my own by and large hapless efforts as executor, there has been something of a resurgent upwelling of interest in Toch, especially back in Europe (where he was featured a few years back in an entire exhibition at the Jewish Museum in his native Vienna), such that virtually all of his string quartets and most of his other chamber pieces and experimental vocal works and operas, and all of his concerti and symphonies have been recorded and released on CD.

Such that, in turn, this summer, fifty years after the passing of my grandmother and sort of in tribute to her, as I decide to revisit that original 1974 biographical text here in the Cabinet, I find that I can cross-link almost all of the compositional references to quite credible musical performances.

So: enjoy!

ERNST TOCH

1887 - 1964

A biographical essay

ten years after his passing

Ernst Toch was born in Vienna on December 7, 1887, into the family of Moritz

Toch, a humble Jewish dealer in unprocessed leather. The Toch family had only

just attained a relative financial security with the generation of Moritz, and the

father assumed that Ernst, his only son, would eventually take on the family

business. There was no musical background or encouragement for the young boy,

and, in later years when his interest in music became more acute, Ernst even faced

considerable opposition from his parents and was forced to pursue his

investigations in secret.

From the very start, nevertheless, this precocious child developed a fanatic interest in the universe of sounds; it was perhaps only natural that in Vienna, a city so deeply engrossed in its rich heritage, such an interest soon concentrated on music. In his first encounter with a piano, in the darkened back room of his grandmother’s pawnshop, the young boy intuited complex melodies. A few months later, the brief tenancy in the Toch household of an amateur violinist allowed the boy his first acquaintance with sheet music; after a few evenings of rapt curiosity, young Toch had puzzled out the fundamentals of musical notation.

In later years, Toch would characterize the epiphany of musical talent in such a culturally desolate family setting as a miracle; and, indeed, the genesis of Toch’s creative genius affords few parallels in the history of music.

Notes which Toch drafted in preparation for an interview, during the last year of his life, include the following remembrance of his unique apprenticeship in musical theory and composition.

I have not studied with anybody...I was left on my own and managed to acquire at length what I learned in a completely auto-didactic way...I made the decisive discovery that pocket scores existed. The quartet I happened to see in the window of a music shop was one of the so-called ten famous quartets of Mozart. I bought it. I was carried away when reading this score. Perhaps in order to prolong my exaltation, I started to copy it, which gave me deeper insight. By and by, I bought and copied all the ten scores. But I did not stop at that. After having copied three or four I became aware of the structure of the single movements. And when I started to copy the fifth, I decided I would only continue with my copying up to the repeat sign, and then try my hand in making that part myself which leads back to the original key (called “development,” as I was later informed). Then I compared with the original. I felt crushed. Was I a flea, a mouse, a little nothing when I compared what I did with what Mozart did; but still I did not give up and continued my strange method to grope along in this way and to force Mozart to correct me. And he not only replaced for me every living teacher but outdid them all.

The unusual circumstances of this education no doubt account, in part, for the special reverence with which, throughout his life, Toch would honor Mozart and the other great masters of the Tradition.

“At the same time,” Toch’s notes continue, “the irrepressible urge to write string

quartets entirely of my own arose and possessed me.” By age seventeen, Toch had already composed six quartets, along with several other chamber pieces, always in secret, each work displaying a more sophisticated grasp of the composer’s craft. One day in 1905, Joseph Fuchs, Toch’s schoolmate, noticed him scribbling furiously under his desk and inquired after the object of such absorbed attention. Informed that these were the final touches of a string quartet, Fuchs asked to borrow the score. A week later Toch received a postcard from Arnold Rosé, the first violinist of the renowned Rosé Quartet, notifying him that his new Quartet, opus 12, had been accepted for performance.

Despite a few early successes of this kind, Toch’s vocation seemed to be in serious jeopardy as he completed his secondary schooling. Continually insecure as to the quality of his ill-begotten talents, Toch saw little hope of any livelihood deriving from his eccentric hobby. And so, somewhat forlornly, he enrolled at the University of Vienna to begin working toward a medical degree.

Suddenly, in 1909, it was announced that Toch had won the Mozart Prize, the coveted award of a quadrennial international competition for young composers which he had entered three years earlier on a lark. The prize included a four-year stipend, with a one-year fellowship to the Frankfurt Conservatory. Elated, Toch journeyed to Frankfurt and reported to the head of the composition department, Iwan Knorr, eager for his first official lesson. “You wanted to study with me?” stammered Knorr. “But I was going to ask if you would allow me to study with you.” And indeed, Toch had already reached full maturity as a composer. His dynamic String Quartet, opus 18, composed shortly after his arrival in Frankfurt, exhibited a masterly control and range.

Toch thereafter remained in Germany, a land already vibrant with anticipation of one of the great creative upsurges in the history of music. Toch was appointed professor of composition at the Mannheim Hochschule für Musik, and through a steady stream of impressive new works, notably including the Violin Sonata, opus 21 (1912), he generated a growing reputation as an important heir to the late Romantic tradition of Brahms.

With the coming of the war in 1914, however, Toch was to fall silent. Returning to Vienna, with a patriotic fervor utterly typical of the Hapsburg Empire’s assimilationist Jews, he volunteered for duty as an infantry platoon commander and was assigned to the front lines in the Italian Alps, where his early military enthusiasm quickly eroded into despair. The numbing tension of battle nearly stilled his creative drive, the only exception being the pastoral Spitzweg Serenade, opus 25, a trio for strings actually composed in the trenches. It was during the Vienna furloughs of these years that Toch’s long courtship of Alice (Lilly) Zwack, the cultured daughter of a Jewish banker, intensified and culminated in marriage (1916).

Soon thereafter, following the intercession of a committee of concerned musicians, Toch was transferred behind the lines to the destitute back-country of Galicia, where he remained until the Armistice. Upon the conclusion of hostilities, Toch quickly returned to Mannheim.

As Toch’s creative urges resurfaced, it became clear that his five years of silence had veiled a profound inner transformation. His new String Quartet, opus 26 (1919), scandalized the audience at its Mannheim premiere. But Toch quickly soared to the vanguard of the Neue Musik movement which was about to electrify Central Europe. Years later Toch recalled some of the forces behind the modernist revolution:

The musical revolution did not come about suddenly: gradually composers began to feel that the old idiom of tonality had exhausted itself and was incapable of utterance without repeating itself, that the once live and effective tensions of its harmonic scope were worn out and had lost their effect. Inevitable at the same time was a strong reaction against over-emotional musical expression, epitomized particularly in the works of Richard Wagner... Indeed, it was refreshing, an inner need, to get away from the over-emotional type of music which was so characteristic of the latter half of the nineteenth century. It was as refreshing as a plunge into cold water on a tropical summer day.

And yet Toch played down the significance of the “New” in the modernist upsurge. He insisted that

The differences at the time they occur are at first very noticeable, and even aggressive. After ten years they are hardly perceptible; after a hundred years they are of interest only to the research specialist. What then remains or is doomed to disappear, that alone decides their worth or lack of worth.

The next fifteen years comprised one of the most prolific phases of Toch’s lifework; they likewise became the years of his greatest public renown. In 1923, following a series of stirring successes, B. Schott’s Söhne, the venerable Mainz publishing firm, signed the young composer to a ten-year contract which would guarantee him a forum for his new work and the steady income with which to pursue it. Toch celebrated the contract by composing his Burlesken for piano, opus 31, whose lively third movement, “The Juggler,” became an instant sensation and remains a modern classic.

Although, in the years before the War, Toch honed his craft through concentration on chamber works (and he was to continue to favor the string quartet with three new compositions between 1919 and 1924), the twenties were to witness the expansion of his range into all musical forms. In particular, Toch turned increasingly toward orchestral compositions, culminating in 1925 with the Cello Concerto, opus 35, followed in 1926 by the Piano Concerto, opus 38. The latter work required more than twenty full-orchestra rehearsals before its sensational performance a few months later at the 1927 Frankfurt International Music Festival, with Walter Frey as soloist and Herman Scherchen conducting. Its enthusiastic reception by audience and critics alike secured Toch’s reputation as one of the foremost composers in Germany.

Toch also turned his attention to the operatic stage and composed his popular The Princess and the Pea, opus 43, soon followed by the charmingly mischievous chamber opera, Edgar and Emily, opus 46, based on an ingenious libretto by Christian Morgenstern.

By 1928 Toch had moved from Mannheim to Berlin, the center of creative excitement in all of the arts, and here he became increasingly interested in cooperative ventures, especially in composing incidental music for the Berlin stage (the tender “Idyll” in the Divertimento for Wind Orchestra, opus 39, for example, was originally conceived as a pastoral interlude for an expressionist production of Euripides’ Bacchae). Toch also attracted considerable attention through his puckish enthusiasm for instrumental experimentation, as in a sequence of complex works which he scored for mechanical piano.

But his most popular innovation came in 1930 with his famous musical prank, the Geographical Fugue for Spoken Chorus, in which he patterned a sequence of rhythmic place-names into a formal fugue {following Toch’s arrival in Los Angeles, later that decade, a young John Cage would see to the piece’s publication in America, in his own translation, which principally involved changing the first word “Ratibor” with its unconveyable rolling R into a more English-friendly “Trinidad”—in the years since the piece has seen thousands of performances, literally dozens of which, many with antic variations, can be found online: see for yourself, or just check out, for example, here and here and here and here, and my own favorite, a solo by somebody’s five year old daughter, here}. Years later, in 1962, Toch would revive the genre in his Valse, arranging the clichés of cocktail party banter into 3/4 time.

So famous had Toch become by 1932 that he was invited to be the first (and last) German composer to tour the United States under the auspices of the remarkable Pro Musica Society. Although Toch was deeply impressed by the vibrancy of American life, and became especially enamored of Southern California, he was somewhat bemused by the provincial musical sensibilities of many of his American audiences. Among his notes for an introductory lecture to a typical Pro Musica concert, we find a passage in which he tried to coax his American listeners into a more receptive attitude vis-à-vis the modernist trends in Europe:

You must listen without always wanting to compare with the musical basis you already have. You must imagine that you inherited from your ancestors different compartments in the musical part of your brain, just as you inherited any other physical or intellectual qualities. Now when you hear a piece from the pre-classic, classic, or romantic periods, the sounds fall without any trouble and agreeably into the already prepared compartments. But when music for which you have no prepared compartments strikes your ear, what happens? Either the music remains outside you or you force it with all your might into one of those compartments, although it does not fit. The compartment is either too long or too short, either too narrow or too wide, and that hurts you and you blame the music. But in reality you are to blame, because you force it into a compartment into which it does not fit, instead of calmly, passively, quietly, and without opposition, helping the music to build a new compartment for itself.

In Seattle, one of the venues where he gave this talk, he subsequently opened himself to questions from the press, one of which concerned his favorite food, to which he answered “Steak Tartare,” resulting in the next morning’s headline coverage:

Toch’s American tour in 1932 was already haunted by the darkening shadow of the Nazi upsurge in Germany. After his return to Berlin, during the few months remaining before Hitler’s final seizure of power, Toch worked intensely on a Second Piano Concerto, opus 61, which was to have its premiere disrupted by brownshirts and its publication canceled by a suddenly “anti-Bolshevik” Schott publishing house. Early in 1933 Toch resolved to flee Germany.

For purposes of his escape Toch profited from his long-scheduled selection (together with Richard Strauss) to represent Germany at a musicological convention in Florence in April, 1933. Toch never returned to Berlin, fleeing instead to France. After he had established himself in a Paris hotel, Toch telegraphed his wife a revealingly coded “all clear” signal, indicating that she and their six-year-old daughter Franzi should join him there: it read, simply, “I have my pencil.”

He had little else. His publisher had abandoned him, his music was being burned, the plates broken. Concerts of his works were canceled; the only traces remaining in Germany of his once vibrant reputation were the doctored photographs gracing the occasional exhibitions of “degenerate music,” and it would be several years before he would even find a new home. Paris, suddenly swollen with German exiles, offered little refuge, and the Toch family soon moved on to London (where, incidentally, he composed the music for the Bertolt Viertel film Little Friend, with screenplay by Christopher Isherwood, who would subsequently deploy his memories of that fraught émigré production in his novella Prater Violet). Toch remained in England for one year, but here, likewise, work permits were in short supply, and the family caromed on to New York. While on the boat to America, Toch composed his lyrically melancholy Big Ben Variations, opus 62, a tone poem evoking the Westminster Chimes as they sounded one foggy midnight to a departing wanderer (the tumult of feelings traversed across the piece perhaps having something to do with the fact that the Westminster Chimes are also the trademark theme for the BBC World News Service).

Like many German exiles, Toch accepted a professorship at the New School for Social Research. Although he stayed in New York for two years, Toch never quite acclimatized himself to the concrete and traffic of Manhattan. In 1936, partly at the instigation of his new American friend, George Gershwin,

Toch was commissioned by Warner Brothers to score a film, and by mid-year he had established residence in Pacific Palisades. During the next ten years Toch would frequently supplement his meager royalties through studio work. Owing to the “eeriness” of his modernist idiom, Toch was quickly typecast as a specialist in horror and chase scenes (the sleigh chase in Shirley Temple’s Heidi, the Hallelujah chorus in Charles Laughton’s Hunchback of Notre Dame), and he was to have a hand in most of the mysteries and thrillers coming out of the Paramount studios for the next several years. During the next decade his scores would receive three Academy Award nominations.

That Toch felt he had at last found a permanent home in the ocean canyons of Southern California, alongside the dozens of other émigrés who were rapidly being drawn there (including Otto Klemperer, Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Marta and Lion Feuchtwanger, Richard Neutra, Salka Viertel

and so many others) is clear from the sudden renewal of his fading creative drive. In rapid succession Toch produced two of his most powerful and striking chamber works, the String Trio, opus 63, and the Piano Quintet, opus 64. These two complex and demanding works represent the culmination of the mature style of Toch’s German years. And yet they fell on deaf ears in the America of the thirties, generating few performances and indeed remaining unpublished until 1946. This unresponsiveness of American audiences to the modernist style is surely one reason (the osmosis of Hollywood film scoring may be another) for the slow bending of Toch’s creative production during the late thirties and forties into a more harmonic and tonal idiom, such as that employed in Toch’s next composition, the Cantata of the Bitter Herbs, opus 65.

In December 1937 Toch received news of the death of his mother in Vienna. While attending the ritual prayers for the dead at a local synagogue, Toch conceived the project of a cantata based on the Hagada, the scripture traditionally read at the family table at Passover, commemorating the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt. Although by no means an Orthodox Jew, Toch perceived a universal human significance in the Passover tale of liberation from the yoke of oppression. But of course this eternal message bore a particular urgency during those horrible months: while Toch was composing the haunting chorus, based on the psalmist’s text, “When Adonoy brought back his children to Zion, it would be like a dream...,” Hitler’s armies invaded Austria and sealed Vienna, the town of his birth. (His now-ten-year-old daughter Franzi sang in the chorus at the work’s Los Angeles premiere.)

The Nazi invasion was to initiate a vertiginous period of depression in Toch’s life. Gnawing anxieties about the fate of trapped friends and relatives (Toch had more than sixty cousins still in Austria) were sublimated into time-consuming negotiations with international bureaucracies in desperate, often futile, attempts to gain their freedom. Meanwhile, the financial pressure of temporarily sponsoring a burgeoning family of dispossessed exiles forced Toch to channel ever-larger portions of his creative life into more lucrative employment. Thus, Toch found himself devoting long hours to film work; his early enthusiasm for the artistic cross-fertilization possible in film gradually soured into bitter disillusionment with the insensitivity of the studio heads, and he came to despise the necessary prostitution of his talents.

Meanwhile, the hours outside the studio were increasingly devoted to teaching, at first privately, and then, after 1940, at the University of Southern California as well. By report of his students (including Andre Previn), Toch was an exceptionally sensitive and effective teacher (perhaps due to the unique genesis of his own vocation, Toch was able to catalyze in others a similarly organic and intuitive apprenticeship in the craft of composition); but it was precisely through this high level of commitment that teaching, even more than studio work, sapped Toch’s energies to exhaustion.

With his hours thus gerrymandered in extraneous pursuits, Toch had decreasing time to devote purely to his own work. Furthermore, the loss of a responsive audience (a situation magnified by labyrinthine difficulties with his American publishers) rendered hollow the few hours he was able to preserve for his creative life. Thus in 1943 he complained to a friend:

For quite some time I am not in a very happy frame of mind. Disappointments and sorrows render me frustrated and lonesome. I become somehow reluctant to go on writing if my work remains more or less paper in desks and on shelves.

Underlying all of Toch’s anxieties was the fear that he had irrevocably squandered his musical vocation, that he had lost everything—even, in effect, his pencil. Indeed, these years were parched by the most harrowing dry spell of Toch’s life. While between 1919 and 1933 Toch had created more than 35 works, during the obverse years from 1933 to 1947 Toch struggled to conceive eight, with barely a single work between 1938 and 1945.

And yet, somehow, perhaps tapping some primal source available only to one brought so low, Toch was on the verge of a stupendous regeneration. In the final months of the war, Toch’s letters tentatively explored the image of the rainbow, metaphor for renewal. For his own renewal, Toch returned to the most fundamental of his forms, the string quartet. “As for me,” he exuberantly wrote a friend, “I am in the midst of writing a string quartet, the first of its kind after 18 years. Writing a string quartet was a sublime delight before the world knew of the atomic bomb, and—in this respect, it has not changed—it still is.” The Quartet, opus 70 (1946), bore as motto the lines of a poem by Eduard Moerike: “I do not know what it is I mourn for—it is unknown sorrow; only through my tears can I see the beloved light of the sun” {see especially the third movement Pensive Serenade, starting around 14:15}.

Toch was simultaneously completing work on his book, The Shaping Forces in Music, the research for which had increasingly possessed him. During the early forties Toch had been startled by the lack of an appropriate textbook for use in his classes, one whose theories could integrate both the modern and the classical styles. With this in mind, he undertook his own survey of the musical literature. Writing one friend, he reported,

I never expected so much fascination to come from investigations on the nature of musical theory and composition. Aspects unfolding to me show why the rules of established musical theories could not be applied to “modern” music, why there seemed to be a break all along the line, either discrediting our contemporary work or everything that has been derived from the past. To my amazement I find that those theories are only false with reference to contemporary music because they are just as false with reference to the old music, from which they have been deduced; and that in correcting them to precision you get the whole immense structure of music into your focus.

Thus Toch’s creative regeneration in the late forties recapitulated the originary apprenticeship of his childhood: once again, through an exploration of the masters, Toch recovered the essential stream of his own vocation.

The years immediately following the War, paradoxically, were to prove the most difficult of all, for now the dense pattern of extraneous obligations threatened to strangle the tentative budding of his renewed vocation. Torn by these conflicting pressures, Toch was felled by a major heart attack in the autumn of 1948.

“I am plowing through a dark and stormy sea,” Toch wrote a friend from his sickbed. But within a few weeks he would deem this seizure one of the most fortunate events of his life. Suddenly, years of sedimented obligations fell away, and he was forced to partake of the calm he so desperately needed. Years of stymied meditations seemed to rush to the surface of his consciousness; he experienced these months as an overwhelming “religious epiphany.” A few years later, in his essay “What Is Good Music?”, Toch would suggest:

Nearness to life, nearness to nature and humanity—who has it? I think the one who contains in himself an irrational, unconquerable bastion, untouched, for which I have no other word but religiousness. To be sure, this quality does not refer to any specific creed. It has nothing to do with a man’s interests and activities, nothing to do even with the conduct of a man’s life. The word “religion” derives from the Latin “religare”—to tie, to tie fast, to tie back. Tie what to what? Tie man to the oneness of the Universe, to the creation of which he feels himself a part, to the will that willed his existence, to the law that he can only divine. It is a fundamental human experience, dim in some, shining in others, rare in some, frequent in others, conscious in some, unconscious in others. But there is no great creation in either art or science which is not ultimately rooted in this climate of the soul, whatever the means of translation or substantiation.

In terms of the dialectic between technique and inspiration which Toch increasingly favored in his later writings, it was clear that his dry years resulted from an atrophy of the spiritual dimension, and it was precisely that dimension which was being replenished in the months following Toch’s brush with death.

As soon as he had recovered sufficiently to travel, Toch returned to Vienna, the city of his childhood, there to complete and unveil the work which was a signal of a new beginning. This First Symphony, dedicated to his childhood friend and secret promoter, Joseph Fuchs, would in time be followed by six others. Such a complete flowering of symphonic form so late in a composer’s life was unprecedented in the history of music.

The first three of these symphonies should be interpreted as a musical triptych, the sustained outpouring of a single source in Toch’s deeply religious and humanistic experience of the late forties. Of one of these symphonies, Toch wrote a friend:

I had meant to call one movement “the Song of the Heritage”; I refrained from it in order not to appear too “literary.” However, the feeling reverberates more or less in all of my present writing, a kind of deep-rooted link between a far past and a far future, and it fills me with great humility and great awe (I mean to be able to be the mouthpiece of such experience).

The First Symphony, opus 72 (1949-50), bore a motto from Luther (of all people!), “Although the world with devils filled should threaten to undo us, we will not fear for God has willed his truth to triumph through us.” The Second Symphony, opus 73 (1953), dedicated to Albert Schweitzer, a man whom Toch revered (he would insist that the symphony was not only dedicated to Schweitzer but “dictated” by him), carried the Biblical motto from Jacob’s wrestling with the Angel, “I shall not let thee go except though bless me.” And finally, the Third Symphony, opus 75 (1954-55), perhaps the finest of them all, bore lines from Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, “Indeed I am a wanderer, a pilgrim on the earth—but what else are you?” Toch would sometimes refer to this work as his “musical autobiography,” and a sensitive listening suggests many motifs drawn from Toch’s own life experience (for example, in the first movement, the military cadences joyously entering, around 5:50, and then splintering catastrophically by 8:20); but just as the motto implicates its reader, so in this symphony, autobiography suggests the microcosm of universal human history. Soon after its premiere, under the baton of William Steinberg in Pittsburgh, the piece was awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

Toch’s creative production would now continue unabated until his death. Restlessly wandering in search of the peace necessary for his composing, Toch divided his last years between Santa Monica, Zurich, and his favorite refuge at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. In one of his most prolific phases, Toch would move during his last fifteen years from opus 71 to opus 98, including the seven symphonies and a final Scheherazade opera, The Last Tale, opus 88 (1960-62), which Toch considered his greatest work (although, {as of 1974} it had yet to see its premiere).

The dramatic, almost epic, scope of the first three symphonies would be echoed in some of the later works, such as Jephta (The Fifth Symphony), opus 89, in 1961. But Toch’s later works generally sounded a more lyrical, and often melancholy, tone, such as that of the pensive Notturno, opus 77 (a nostalgic fantasy born of an evening walk in the woods of the MacDowell Colony in 1953), or the poignant Fourth Symphony, opus 80 (a 1957 memorial for the Colony’s founder, Mrs. Marian MacDowell).

During those final years Toch worked at a furious pace, haunted by the specter of the time already lost, overflowing with musical ideas he feared he might never complete. “Never in my life has writing come as easily to me as it does now,” he told one friend. “I am writing myself empty,” he confided to another. But, although the last works were composed with an almost Faustian intensity, they breathe a serene, sometimes almost elfin, leisure and calm. While the compositions between 1947 and 1955 seemed to derive power from their homage to the Tradition, the works after 1955 tended toward an increasingly personal, almost introverted, idiom. He abandoned many of the classical forms and seemed to disdain rigid architectonics in favor of what appear almost roving fantasies. Often in the final two symphonies and the two sinfoniettas (opuses 93, 95, 96, and 97, all composed during his last year), the lyric line breaks free of all restrictions. The orchestration becomes leaner and clearer, partly perhaps because of the pressure of the relentless passage of time.

In early September, 1964, Toch was suddenly hospitalized in Los Angeles; he was dying of stomach cancer. In a last note to his wife, he apologized for the eccentricities and inconveniences of years in service to the muse, but, he concluded, it could not be helped, because

Ich treibe nicht, ich werde getrieben

Ich schreibe nicht, ich werde geschriebenI do not press, I am pressed;

I do not write, I am written.

Ernst Toch died on October 1, 1964. The scribbled pages found by his bedside contained the early drafts of a new string quartet.

During his last years, Toch would sometimes refer to himself wistfully as “the world’s most forgotten composer,” and his melancholy joke betrayed a certain painful validity. But if Toch’s music seemed in temporary eclipse, this was in part because of the integrity and independence of a lonely artist, leader or follower of no school, who insisted on striking the proper balance between innovation and tradition, and hence found himself dismissed simultaneously as too old-fashioned by the avant-garde and too modern by the traditionalists. But with the passage of time these artificial distinctions are beginning to fade, and Toch’s oeuvre is being reassessed in terms he would have preferred, as a single link in the long chain of the musical tradition. And as such, Toch’s music is prized for the mastery of its craftsmanship and the depth of its inspiration.

Lawrence Weschler

Grandson of Ernst, son of Franzi

October 1974

*

Postscript to the Foregoing

So, that was coming on 48 years ago. From 22 years before that, shortly after I was born, there’s a photo of my mother Franzi showing me off to her parents Ernst and Lilly, and, presumably from the same day, another of Ernst holding me up on his own:

Funny how he seems to be holding me with the same grip he held whatever that creature was that he was cusping in that photo of him above with Klemperer and Schoenberg in Will Rogers State Park. The years passed (Ernst passed) and teenage me would find myself cohosting guests when Lilly held soirees at their Santa Monica place. After dinner, we’d retire to the study/living room, and she’d seat herself (without comment) beneath a painting of her Viennese great grandmother, and have me sit alongside a bust of Ernst that had actually been done by Anna Mahler, the daughter of Gustav Mahler, and we’d blow everybody’s minds:

You can see, at any rate, where I got my nose. (For more on which, see the Footnote in Issue #5 of this Wondercabinet.) More recently, my friend the wet-collodion master Stephen Berkman tried showing me the intricacies of the mid-nineteenth century photographic technique by way of a pair of photographic captures of me that ended up looking uncannily like the ones August Sander had done of my grandfather back in the Weimar twenties:

In fact, it can get a little hard to tell just who is who’s grandfather in those matched pairings.

Which in turn reminds me of that photo, earlier referenced, of Ernst at the MacDowell Colony around 1953. When I was a baby a large version of that portrait hung immediately above my crib, and I remember (or fancy myself remembering) how that was just about the oldest thing I had ever seen in my life. Good lord. I only mention that because a few years back, when I spent a season of my own at the MacDowell Colony (as it happens finishing my book on Oliver Sacks), I tracked down the very cabin in the background and snapped a photo of myself.

As I say, good lord: how did that happen?

Anyway, as I also say (in partial answer to that first question): coming on fifty years! Though, indeed, there has been movement of a sort in the recuperation of Toch’s reputation: all those CD’s, a brace of performances here and there (usually there, specifically in Germany) at which I am occasionally invited to speak. About ten years ago, at the Kammermusikhaus of the Berlin Philharmonic, I was telling the very attentive audience about “the echolessness and benign indifference of the vast American expanses” (as Ernst Krenek had parsed things) that confronted the émigré composers once they arrived in the US in the thirties, and I told the “Eats Raw Meat” story and confirmed that, yeah, by comparison with Berliners of the twenties, the Angelenos of the thirties really were a bunch of yahoo dolts. The audience loved it, laughed, just lapped it up. “But at least there,” I continued, “they weren’t trying to kill him.”

On the other hand, it is especially there in Germany and to a lesser extent Austria, that there seems to be something of a rising floodtide of appreciation of all that was lost, culturally, in the vast Hitlerite expulsion. For example, it was in a little provincial opera house in the former East Germany that Ernst’s final opera, The Last Tale, finally did get its premiere (and I was there to chronicle the event in a piece for the Atlantic—see in particular the prolog and the first and final sections, as the middle two sections pretty much recapitulate what you will have just read here). And that exhibition at the Vienna Jewish Museum, back in 2010, “Ernst Toch: Life as a Geographical Fugue” spawned a catalog, put together by the show’s curator Michael Haas, which, though out of print, is well worth seeking out. (Incidentally, my own daughter, Toch’s great-granddaughter, Sara, who is something of a linguist, joined me for that opening and pointed out at the news conference on the eve of the show’s opening—attended by literally dozens of cultural reporters—that the word “fugue” derives from the Latin for “flight” as in “flee” and thus shares a common root with the word “refugee.”)

Meanwhile, especially back in the early years of my own career, in the mid-seventies, working at the Oral History Program at UCLA (where I’d started out by editing Lilly’s own two-volume 1,000-page transcript in the months immediately after her death), I became something of an authority on the émigré scene myself, going on for example to record and edit the reminiscences of Marta Feuchtwanger and Dione Neutra, among others. In 1997, when the LA County Museum of Art followed up its seminal recreation of the Nazis’ 1938 Degenerate Art show in Munich with a sequel exhibition, “Exiles and Emigrés,” tracing the subsequent fate of all those stigmatized artists and musicians, I contributed the catalog essay on “Paradise: The Southern California Idyll of Hitler’s Cultural Exiles” (which included a detailed map to all of their homes), which you can find collected, along with many other such writings of mine, in the “My Grandfather and Other Emigrés” section of the Archive at my website. There you will also find another piece I contributed to The Threepenny Review on my adventures early on producing an LP recording of Ernst’s Geographical Fugue, across the stupefyingly boring process of which (all those endless takes and then the hour upon hour spent editing the final version, syllable by syllable, across reels of actual tape) I ended up composing a Medical Fugue of my own (“Syphilis, and the tight tendinitis and the pig trichinosis and the clap {clap} gonorrhea,” and so forth). For that matter you can also find there the actual score of both Fugues, my grandfather’s and my own.

With the passing years, people keep seeming to find their way to Toch, and with the help of Dina Ormenyi of the Toch Society in LA [dormenyi@yahoo.com], the likes of musicians Annette Kaufman of LA and Frank Dodge of Berlin and Christopher Caines of New York and Anna Magdalena Kotkis of Vienna; and conductors Leon Botstein and Alun Francis (and all the folks over at CPO Records); and academics and writers Michael Haas and Dorothy Crawford and Constanze Stratz and Heiko Schneider and the late Diane Jezic; and the librarians at the Ernst Toch Archive of the UCLA Library’s Department of Special Collections, Toch’s audience continues, albeit gradually, to generate anew.

For example, a bit over a year ago, I was just minding my own business (as all my stories begin), when suddenly I got a note from one Makiko Hirata, a young Japanese-born pianist now based in LA, who’d herself recently become somewhat besotted with Toch. She’s a remarkable artist, well worth looking into on her own merits. But anyway, one thing led to another, and earlier this year, she and I collaborated on a conversation/recital at her alma mater, the Colburn School in LA, a video of which I include in the AV Room below.

* * *

A-V ROOM

An illustrated recital / talk on the Life and Music of Ernst Toch

with pianist Makiko Hirata

accompanied by the composer’s grandson, Lawrence Weschler

May 12, 2022 at the Colburn School, Los Angeles

NOTE: The above video sometimes takes 25 seconds to start, so give it time. Makiko and I are eager to take our continually evolving act on the road, so if any of you know of anyone or anywhere that would like to have us, please do let us know by way of weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

Animal Mitchell website.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

In celebration of the opening of a big Federico Solmi retrospective over the river in New Jersey, my catalog essay on the extraordinary career of this Italian-born (butcher’s son) artist; and more…

We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Wow, Ren. You don’t have the music gene, but he certainly had the literary gene. The bit about helping the music to build its own compartment for itself (same basic advice I give to people looking at strange pictures)… the irrational, unconquerable bastion, untouched… and what a title THE SHAPING FORCES IN MUSIC is. Also, there needs to be some cool downtown string quartet of Juilliard drop outs called EATS RAW MEAT.