WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Drew Friedman visions Hitler’s cultural exiles remanded to their L.A. Paradise during the thirties and forties; and a further masterpiece by Art Spiegelman’s find, Sy Lewen.

* * *

The Main Event

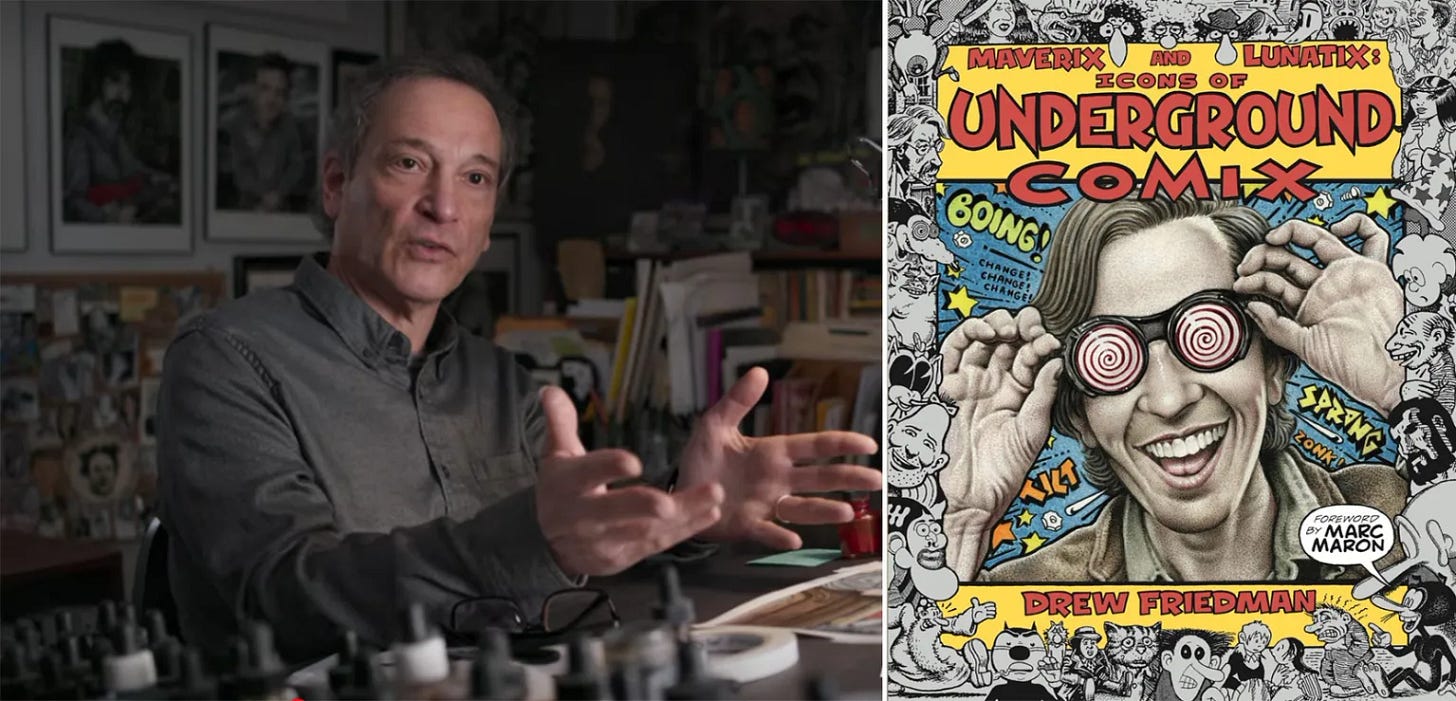

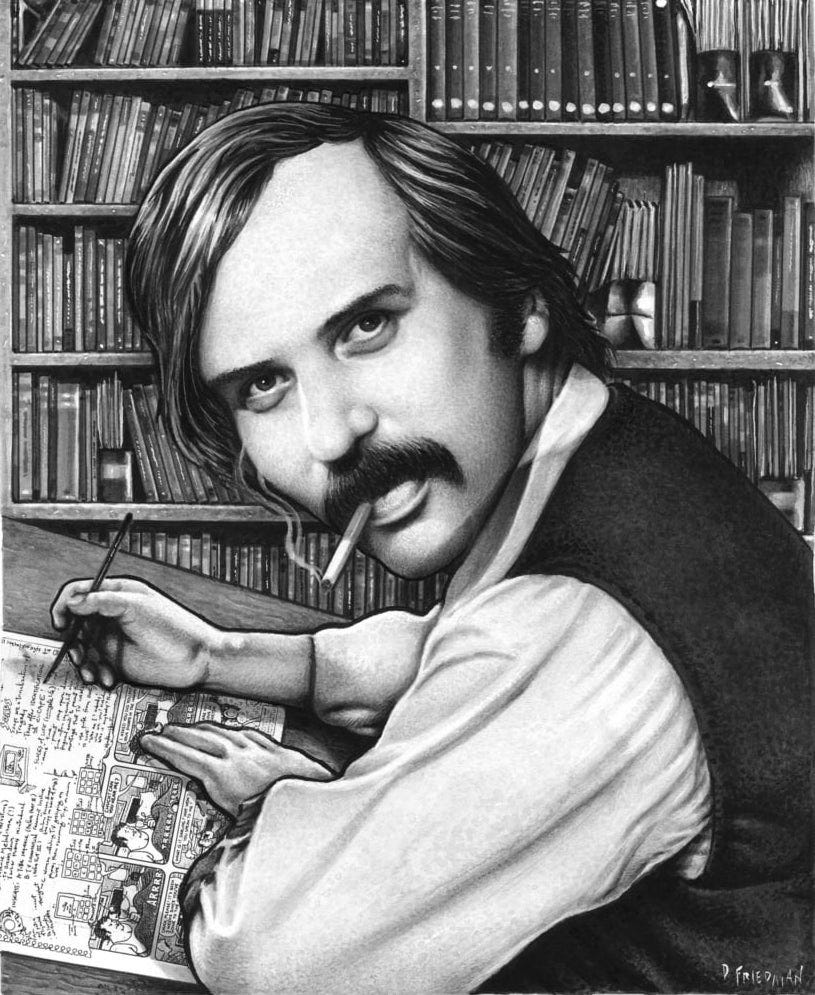

Last week’s then-preview of Art Spiegelman’s celebratory survey of the work of his late nonagenarian friend Si Lewen, including the latter’s achingly masterful sixty-plus black-and-white panel dirge on war across time, “The Parade,” at the James Cohen Gallery in Tribeca (since-opened and now up through April 27) got me to thinking about another of Art’s friends, his onetime student Drew Friedman, or more specifically the latter’s achingly evocative portrait of his eventual teacher back in his own youth, included in his marvelous recent volume of over one hundred such portraits Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix (Fantagraphics, 2022).

And that in turn reminded of a time I myself got to work with the deliriously talented young Mr. Friedman, back in the 1990s. In 1991, Stephanie Barron and other curators at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art had had the inspired idea of remounting as much as they could get their hands on of the contents of the infamous Entartete Kunst/Degenerate Art show that the Nazis had themselves mounted in 1937 in Munich

(the most attended show in history of the Third Reich, especially when it then circulated to ten other cities, notwithstanding the status of its hugely derided avant garde and modernist contents—works by my own composer grandfather Ernst Toch had been prominently featured in the Munich show’s musical wing, with photos of him burnished by conspicuous retouching of his already quite prominent nose).

In 1997, when the team at LACMA decided to follow up that show with a sequel entitled “Exiles + Emigres,” on the farflung subsequent fates of many of those “degenerate” cultural figures, they asked me to provide the catalog essay on the community of such folk who had specifically gathered in the LA area. Hence my contribution, “Paradise: The Southern California Idyll of Hitler’s Cultural Exiles,” which in addition to a moderately lengthy thematic essay, and a carefully researched four-page Movie Star-like map to all of their homes (it turned out that they virtually all lived within one mile to either side of Sunset Boulevard as it wended its way from downtown/Silverlake to the sea), included a series of boxed side-vignettes relating some of the more uncanny instances of cultural misprision that had characterized their tenure in the Southland.

On the eve of the show’s opening, I suggested to the editors at LA Magazine that they might like to run a series of those vignettes, and as I think about it, I believe it was Art who suggested that we sound out Drew Friedman to see whether he’d be willing to illustrate them. We did, he was, and the result proved its own conflation of the exquisitely apt and the perfectly uncanny.

***

From the Archives

FROM HITLER TO HOLLYWOOD

with drawings by Drew Friedman

Los Angeles magazine, March 1997

During the 1940s, L.A. became a refuge for one of history’s greatest gatherings of artists and intellectuals. The following portfolio, inspired by this month’s “Exiles and Emigrés” exhibit at LACMA, celebrates the experiences of these strangers in an even stranger land.

*

Thanks to Adolf Hitler, Los Angeles enjoyed an extraordinary intellectual golden age during the 1930s and ‘40s. Fascism drove the cream of Middle European culture into exile, and for a time a large portion settled in L.A., to sometimes surreal effect. In 1941, for instance, you could regularly attend Sunday brunches at Salka Viertel’s house on Maybery Road in Santa Monica and find Thomas Mann, Arnold Schoenberg, or Bertolt Brecht sipping orange juice with Charlie Chaplin or Johnny Weissmuller.

Not all of L.A.’s émigrés were fleeing the Nazi onslaught, but even the ones who’d arrived before 1933, when the Nazis took power, were transformed into instant refugees when safe return to their homeland became impossible. The exiles congregated in Southern California for many reasons. There was the Mediterranean climate, the same balmy ambience that for centuries had exerted a hypnotic pull on the imaginations of Northern Europeans. Los Angeles also offered Hollywood, with its abundant—if often illusory—employment opportunities. But after a certain point, the simplest reason was that so many others had already settled here: They’d achieved a vital mass that began to exercise its own magnetic attraction.

In addition to maestro Weissmuller’s brunch companions, Los Angeles welcomed composers Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Erich Korngold, Hanns Eisler, Ernst Toch, and Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco; conductors Otto Klemperer and Bruno Walter; musicians Gregor Piatigorsky, Jascha Heifetz, Jacob Gimpel, Artur Rubenstein and Vladimir Horowitz; writers Heinrich Mann, Franz Werfel, Lion Feuchtwanger, Vicki Baum and Anita Loos; architects Richard Neutra and Rudolf Schindler; social critics Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer; artists Man Ray, Max Ernst, and Oskar Fishinger; and directors William Wyler, Billy Wilder, Otto Preminger, Max Reinhardt, Jean Renoir, Berthold Viertel, Fritz Lang and on and on.

The émigré era was relatively brief, but its effects can still be seen in everything from California moderne housing design to the repertory of the L.A. Philharmonic, and the collections of L.A. art museums on through to late-night reruns of Hogan’s Heroes.

*

GO WEST, JUNGER MANN

“Wherever I am,” the novelist Thomas Mann solemnly used to say, to the hearty concurrence of his fellow émigrés, “there is Germany!” But Los Angeles was very pointedly not Berlin. The rich tradition of popular immersion in high culture that had grounded creative life over there was replaced here by what composer Ernst Krenek once characterized as “the echolessness of the vast American expanses” or what conductor Henri Temianka often described as Southern California’s primary trait: “an unlimited indifference and passive benevolence toward everything and everybody.”

Emigrés used to console one another with the story of the two dachshunds who meet one day on the Santa Monica Palisade. “Here it’s true I’m a dachshund,” one tells the other. “But in the Old Country, I was a Saint Bernard!”

And there were many ex-Saint Bernards there on the Palisade. One of them, the writer Bruno Frank, used to make regular evening pilgrimages to the palm colonnade, where he’d occasionally startle strolling passers-by. “There,” he would announce wistfully while pointing out over the water toward the setting sun, “there lies Germany.” No one had the heart to tell him that, well, actually no, there—lay Japan.

*

THREEPENNY PITCH MEETING

“Wherever I go,” the great playwright Bertolt Brecht wrote in a poem about his Hollywood exile, “they ask me ‘Spell your name!’/And, oh, that name was once accounted great.” But what had he done for anybody lately? “Every morning to earn my bread,” he recorded in another poem (titled simply “Hollywood”), “I go to the market where lies are bought./Hopefully/I line up with the sellers.”

It remains one of the abiding scandals of the Hollywood ‘40s that, during the six years of his sojourn here, Brecht, arguably the premier playwright of the twentieth century, managed to see only a single one of his screenplays carried through to completion—Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (which Brecht subsequently disowned).

On the other hand, maybe the studio heads deserve a moment’s sympathy as well. In his memoirs, Gottfried Reinhardt recalls how they were regularly getting pitched such Brechtian brainstorms (delivered in his “unadulterated Bavarian accent”) as a riveting proposal for a film about the “production, distribution and consumption of bread.”

*

A WALK ON THE BEACH

FROM THOMAS MANN’S DIARY:

Thursday, April 14 [1938], Beverly Hills; Got to sleep late, Phanadorm. Drank coffee. Wrote a page and was stimulated. Outing to the beach with the Huxleys [Aldous, author of Brave New World, and his wife], the weather clearing rapidly and becoming warmer, where we got out and took a rather long walk along the glistening blue and white ocean at ebb tide. Many condoms on the beach. I did not see them, but Mrs. Huxley pointed them out to Katia.

*

MAHLER’S FIRST

S.N. Behrman once described a typical dinner party in the ‘40s at the home of novelist Franz Werfel (author of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh and The Song of Bernadette), then married to the redoubtable widow of the composer Gustav Mahler. Alma Mahler Werfel (as she preferred to be called until Werfel’s death, whereupon she recast herself as Alma Werfel Mahler) spent most of the evening regaling her guests with tales of her amorous conquests: how the painter Oskar Kokoschka had been so in love with her that he used to traipse about with a life-size doll of her; how an intoxicated Alban Berg had dedicated his opera Wozzeck to her; how architect Walter Gropius had been a devoted love slave. “But by far the most interesting person I have ever known,” she concluded, glancing pointedly at her husband, “was Mahler!” To which poor squirming Werfel could only nod in fervent agreement.

*

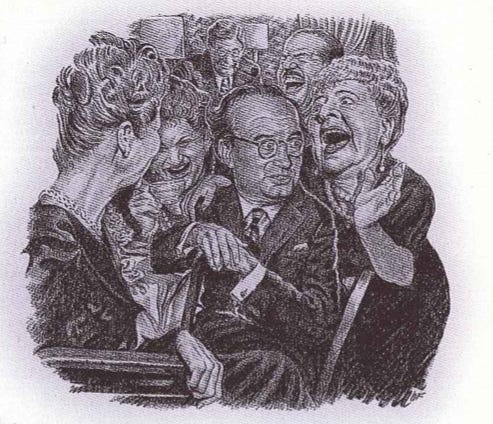

WHEN IN AMERICA

It was entirely possible for émigrés in L.A. to go weeks without having to dust off their faulty English. In a loving memoir of his director-father Max, Gottfried Reinhardt describes an evening at the Clover Club, a gambling casino on Sunset Boulevard, in the company of the legendary Otto Preminger. As it happened, they were the only two non-Hungarians at the roulette table, and the agglutinative language of their neighbors began to grate on Preminger. Finally, he pounded the table and shouted, “Goddamn it, guys, you’re in America—speak German!”

*

DOCTOR FAUSTUS, I PRESUME?

The inbred émigré scene in Los Angeles was occasionally given over to bizarre eruptions of scandalous enmity. Perhaps the most famous of these involved the 1947 publication of Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, written while the Old Master lived in Pacific Palisades. The protagonist in this complex allegory of the demonic rise of Adolf Hitler and the selling of Germany’s soul was a spectacularly brilliant composer whose increasingly feverish musical explorations—he was also apparently suffering from some sort of venereal disease—culminated in the creation of a twelve-tone compositional system remarkably like that of Arnold Schoenberg, the great Austrian composer who had also relocated to L.A.

Soon after the book’s publication (and, according to several accounts, considerably goaded on by a slyly meddling Alma Mahler), Schoenberg exploded. He was enraged that his role as the actual creator of the twelve-tone method had not been acknowledged in the text—while at the same time, he was mortified that readers might mistake him for Mann’s venereal protagonist. Novelist Lion Feuchtwanger’s wife Marta, herself one of the doyennes of the émigré scene, used to tell a story about the chance encounter she had with Schoenberg at the Brentwood Country Mart around this time. Reaching for a grapefruit, she suddenly heard the composer at the other end of the aisle shouting (thankfully) in German: “Lies, Frau Marta, lies! You have to know, I never had syphilis!”

*

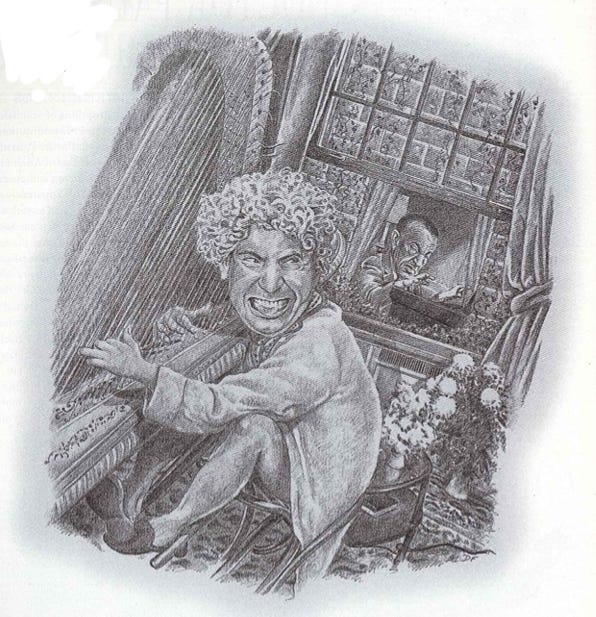

PLUCK YOU!

Harpo Marx used to steal away for harp practice in a secluded rented bungalow at the Garden of Allah, off Sunset. One weekend, as he subsequently recalled in his 1961 memoirs, his serenity was upended by a pianist who took up residence in an adjacent bungalow and began pounding away. Harpo complained to the management, insisting that the other fellow would have to move, since, after all, he’d been there first. The management informed him that, on the contrary, the other fellow was the great Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, and he was staying as long as he liked.

“I was flattered to have such a distinguished neighbor,” Harpo wrote, “but I still had to practice. So I got rid of him in my own way. I opened the door and all the windows of my place and began to play the first four bars of Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-sharp Minor, over and over, fortissimo. Two hours later, my fingers were getting numb. But I didn’t let up, not until I heard a thunderous crash of notes from across the way, like the keyboard had been attacked with a pair of sledgehammers. Then there was silence. This time it was Rachmaninoff who went to complain. He asked to move to another bungalow immediately, the farthest possible from that dreadful harpist. Peace returned to the Garden.”

*

WHERE THE GIRLS ARE

In the mid 1950s, a German émigré writer named Frederick Kohner watched, mystified, as his Americanized teenage daughter learned to surf on Malibu Beach. Kohner decided to write a fictionalized account of his daughter’s exploits, deploying as the book’s title the nickname she had acquired at the beach: Gidget. Around the same time, a Russian émigré named Nabokov living in Ithaca, New York, published a story about another American teenager called Lolita. Both books concerned girls coming of age, both were quintessentially American, and both were composed by émigrés.

*

HELLO. . .AND GOODBYE

The conclusion of the war, which should have suffused the émigré community with the satisfactions of victory, ironically launched a period of increasing anxiety as their adopted homeland lurched from its external war against fascism into an internal obsession with communism. One of the first staging grounds for this new hysteria proved to be Hollywood, rife as it was with suddenly suspect “foreign” influences. The early broadcasts and papers in which these émigrés had once cried out against Nazism were suddenly being cited against them as evidence of long-standing “communist sympathies” or—and this was the official charge—”premature antifascism.” Many were persecuted, to varying degrees: writers Salka Viertel and Lion Feuchtwanger, for instance, and architect Richard Neutra. Others were hounded from the country: Brecht and composer Hanns Eisler. Others simply left in disgust.

Among the latter group was Thomas Mann, who, with enormous pride, had become an American citizen in 1944. In 1950, however, he wrote to a friend: “I am very much attached to our house, which is so completely right for me, and I also love the country and the people, who have certainly remained good-natured and friendly…[but] the political atmosphere is becoming more and more unbreathable.” A year later, in another letter, he wrote: “I myself am nothing but a bundle of nerves, trembling at every thought and word. . . .Have people ever had to inhale so poisoned an atmosphere, one so utterly saturated with idiotic baseness?” Within a few months, Mann decided to emigrate once again, this time to Switzerland, where he lived out his remaining three years. As he was preparing to leave the United States, he made reference in another letter to a story he’d heard about a pair of friends. One was leaving a shattered Europe and sailing to America while the other was fleeing America and returning to his beloved homeland in Europe. As their ships passed on the high seas, they recognized each other and simultaneously cried out in horror: “HAVE YOU GONE CRAZY?”

* * *

ARTWALK FOLLOW-UP

Art Spiegelman’s Sy Lewin show indeed opened this past weekend at the James Cohan Gallery in Tribeca, and as much as I marveled at the star-turn of its Parade series (as anticipated in our previous issue), I was perhaps even more gobsmacked by a previously entirely unknown and never-before-exhibited chef d’oeuvre from 1964, at a moment when, as Art related last time, Lewen’s

darkness returned, and galleries tried to dissuade him from his bleaker work. Finally, he stated, “Art is not a commodity. Art is priceless!” and withdrew from the art world—though not from painting. He told me, “Of course, when something is priceless it’s also worthless.” So, in his new obscurity, he painted more prolifically than ever, free to now cut up “worthless” old paintings and collage them into new and more complex works.

Which, I suppose, is how we end up with something like his Great Feast, a voracious wall-commanding nightmare gyre of a combine—

“Bosch’s Last Supper,” as one visitor at the opening framed it, to which Spiegelman himself countered “His Guernica!”

Photographs really don’t give you a proper sense of the power, the self-immolating presence, of the thing. But here are a few more:

Trust me. It’s worth the visit.

And, should you need any more encouragement, Art and Dan Nadel will be there at the gallery in person in conversation on Saturday April 6th at 2 pm.

* * *

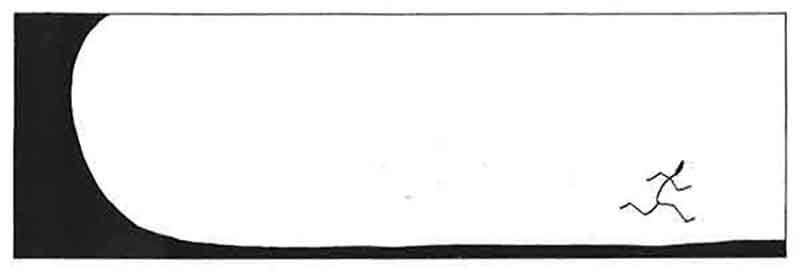

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

I just recently found out that Drew Friedman is Bruce Jay Friedman’s son, which blew my mind. I discovered both of them at the same time in college in the early 90s but had never connected them. Genius ran in that family.

A big fan of Drew Friedman - about 10 years ago he kindly sent me a copy of the Different Drummer poster. Our inspiration while working on songs. An article Drew wrote: https://drewfriedman.blogspot.com/2011/07/different-drummer.html