March 21, 2024 : Wondercab Mini (63A)

ARTWALK

Si Lewen, curated by Art Spiegelman, at the James Cohan Gallery in New York City, opening this coming weekend…

A thoroughly bracing survey of the late Si Lewen’s work, including his stunning anti-war epic suite of stark monochromatic drawings, The Parade (from 1956-7) in its first complete showing ever in New York City, will be opening this Saturday March 23rd (at 3 pm) at the James Cohan Gallery in Tribeca (52 Walker Street) through April 27th. From the Gallery’s own description, interleaved with selected images from the suite:

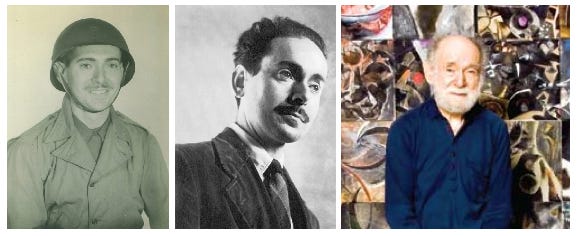

Si Lewen: The Parade presents an epic series of sixty-three drawings by Polish-born artist Si Lewen (1918-2016). Lewen, an immigrant who lived and worked in New York and Pennsylvania, witnessed the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945 while serving in the United States Army as a member of an elite force of native German-speaking G.I.s called the Ritchie Boys.

In the 1950s he published a cutting-edge graphic novel that directly responded to these horrors, and this exhibition presents the full set of drawings that were created specifically for this book project.

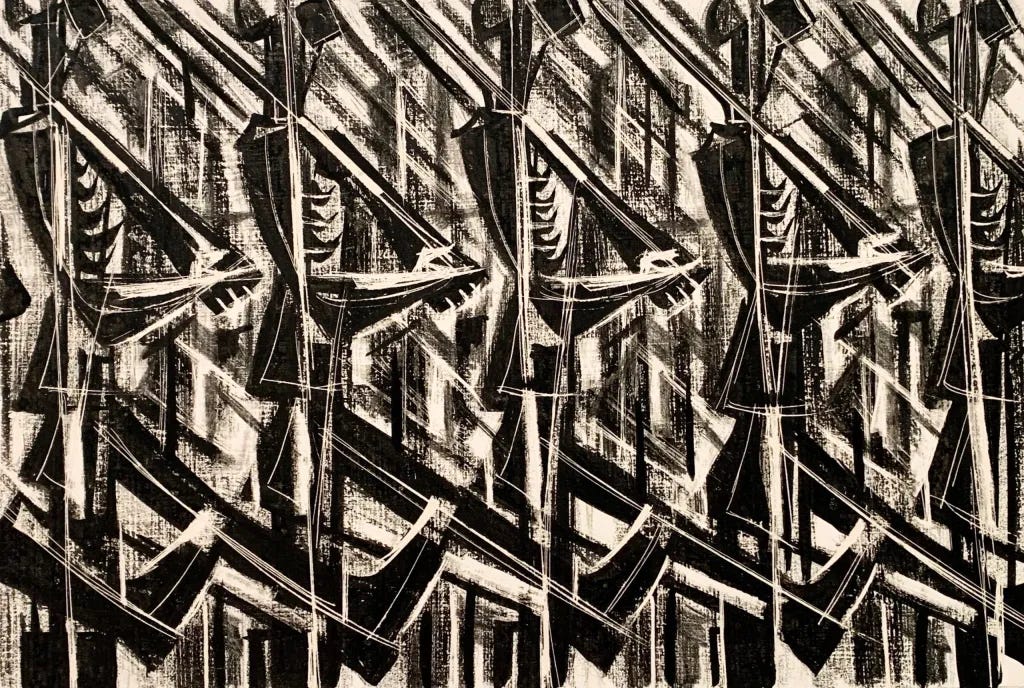

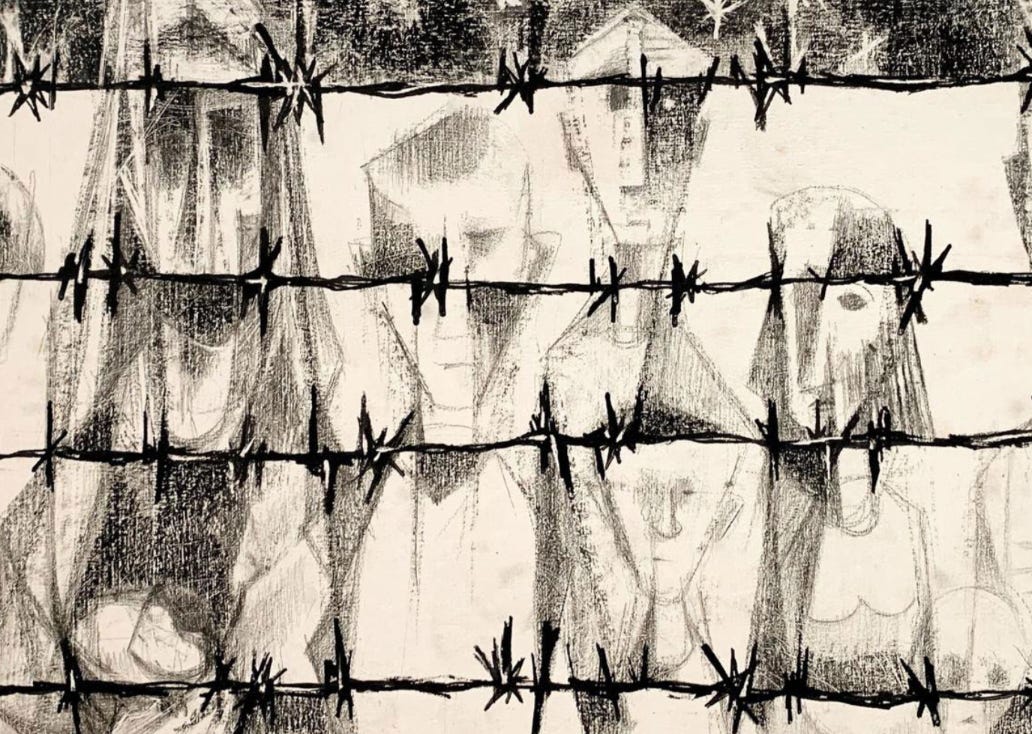

Without a single written word, The Parade speaks to cycles of war, the seductive glory and pomp, followed by soldier enlistment, community deprivation, devastating destruction, death, and heartbreak. When the war ends, the cycle repeats. The artist was born during the final days of World War I; the armistice parades after that conflict, the rise of Nazism, and the brutal violence of World War II, all inform his haunting tale.

The Parade begins with children and families making their way toward a celebration for the men that will soon be sent off to war. Over the course of the wordless narrative, Lewen explores the destruction and despair that takes hold of communities as violence builds and lives are lost. This important and rarely-seen body of work powerfully engaged viewers when it debuted nearly seven decades ago and remains prescient and timely for audiences today.

A Polish Jewish refugee, Si Lewen grew up in Germany, where he observed the political and cultural upheaval happening around him. In 1933, when Hitler came to power, he fled to France with his brother and later immigrated to the United States.

His drawings are held in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, among others. Last year’s exhibition at the De Menil in Houston marked the first United States presentation of the complete set of works from The Parade, and this will be its first full presentation in New York.

*

PERSONAL INTERLUDE

I myself can’t help but notice the remarkable thematic similarity between Lewen’s series and a wrenching oft-noted autobiographical passage from the first movement of my own grandfather Ernst Toch’s Pulitizer Prize winning Third Symphony (the military cadences boisterously entering, around 5:50, and then splintering catastrophically by 8:20) from almost exactly the same time period (1955-56).

*

SPIEGELMAN ON LEWEN

The Cohan Gallery’s Lewen show is being curated by Art Spiegelman, who eight years ago was seeing to the publication of an accordion-style rendition of the master’s Parade. At the time (October 25, 2016), he penned a short column for The New Yorker, recounting his own history with the graphic novel and surprise late-life friendship with the artist, who had only just died a few months earlier—passages from which piece follow below:

My friend Si Lewen, the painter, died three months ago, a little shy of his ninety-eighth birthday. In one of our last phone conversations, I asked him if he was backing Bernie or Hillary. He’d often told me that he was to the left of Karl Marx, so I was surprised when he said, “Hillary, of course!” When I asked why, he told me that, unless we evolve into a matriarchy, we’re all doomed. It’s hard to find father figures in one’s sixties, and, though Si was more like a batty uncle, I miss him.

I first met Si when he was a spirited and elfin ninety-four-year-old who still spent most of his waking hours painting—as he had since childhood. I’d stumbled onto his book The Parade, from 1957, while researching wordless picture stories—obscure precursors of today’s graphic novels that briefly flourished between the two World Wars. The Parade, obscure even by this genre’s standards, was drawn shortly after the Second World War, but was conceived while Lewen, a Polish Jewish refugee from Germany, was a member of an élite force of native German-speaking G.I.s who were in Buchenwald right after it was liberated.

After the war, Si resumed painting. Much to his astonishment, he found that he’d banished “black in all its overtones” from his palette, despite his traumatic past. Luminescent and colorful, his canvases from the nineteen-fifties and sixties often sold for ten thousand dollars and more. But, inevitably, his darkness returned, and galleries tried to dissuade him from this bleaker work. Finally, he stated, “Art is not a commodity. Art is priceless!” and withdrew from the art world—though not from painting. He told me, “Of course, when something is priceless it’s also worthless.” So, in his new obscurity, he painted more prolifically than ever, free to now cut up “worthless” old paintings and collage them into new and more complex works.

The Parade is a modernist dirge of a book that still packs an emotional wallop, telling the story of mankind’s recurring and deadly war fever. Einstein wrote Si a fan letter after seeing the drawings in 1951, saying, “Our time needs you and your work!” It doesn’t take a genius to see that this is still true today, so Si and I collaborated on an expanded “director’s cut” version of The Parade, remastered from the original art and published, this month, as a long accordion-fold book.

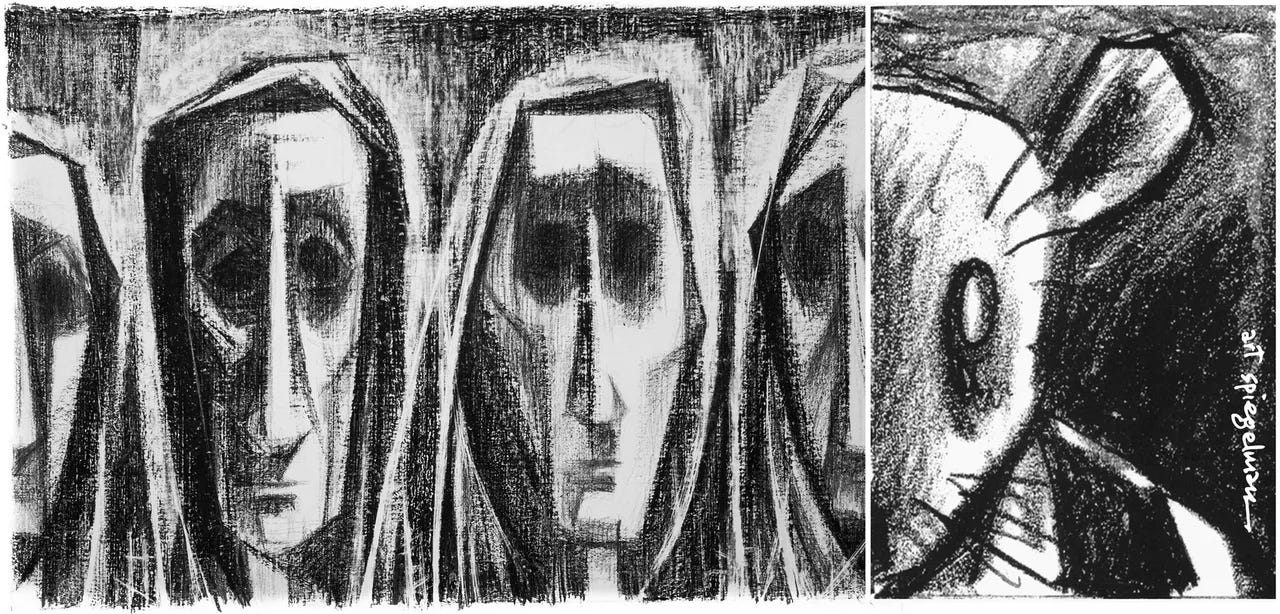

On the usually blank verso side is a monograph of Si’s life and work that shows some of his paintings, including from his series “Ghosts,” which had grown to two hundred or more shroud-like canvases between 2008 and 2015, when he had to hang up his brushes.

I brought the first advance bound proof of the book to him in his assisted-living facility, in Pennsylvania, as soon as it arrived. He couldn’t put it down, and he died ten days later. It was, eerily, as if seeing his life’s work acknowledged gave him permission to die.

*

POSTSCRIPT

Spiegelman’s “curator’s note” to the current exhibition recapitulates some of the points made in that New Yorker piece eight years ago, but it ends like this:

Si would be proud to find his work seen again in New York City, where he arrived at seventeen as a Polish Jewish refugee and continued to develop as an artist—but Si's ghost would break down weeping to return to a world with a new appetite for authoritarianism and antisemitism and to find rivers of blood flowing in the Ukraine and Gaza. It doesn’t take a genius to see that our time needs Si and his work now more than ever.

Spiegelman will be in attendance as the show opens at the James Cohan Gallery’s 52 Walker Street space in Tribeca this Saturday, March 23rd, from 3 to 6 pm. Two weeks later, on April 6th, at 2 pm, Spiegelman will join the redoubtable Dan Nadel in conversation about Lewen, everyone welcome.

* * *

AND NOW THIS

Yes, that was me, being gently ridiculed this past Sunday (3/17/24) on John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight as part of an extended segment on student loans.

I have no idea how I ended up there and initially couldn’t decide whether doing so was making me feel diminished or exalted. In the end, I realized it had momentarily given me a heightened sense of existence: I am mocked therefore I am. Derisus sum ergo sum. QED

See you next week!

What a great artist. NEW to me. Thank you.