WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

A round-robin of paradoxical circles, followed by a deep dive into New York’s churning subways by way of Ed Hotchkiss’s photographs.

* * *

A ROUND-ROBIN OF PARADOXICAL CIRCLES

That annoyingly confounding little doodle of mine with which we concluded our Cabinet two weeks back kept thrumming around in my head across the days since, reminding me of something, I wasn’t quite sure what, and then, oh yeah, it came to me: a similarly paradoxical involuted image, photographic this time, which I kept coming upon a few months back in reviews of a new book, Very Pictorial Conceptual Art edited by David Campany and revisiting some of the finest of the funny-serious work by that minor-major West Coast photographic jester-wizard of the seventies and eighties Robert Cummings, who died, as it happens, only three years ago at age 78.

And, as I say, this one photograph in particular, which kept recurring from review to review, a deceptively simple though compoundingly vertiginous portrait of the artist as a young scamp entitled, self-evidently, 67-Degree Body Arc Off Circle Center (tap image to enlarge). For indeed, what had we here? A self-portrait in which the young master stood in profile in dark pants and a white tee-shirt with his stomach jutted out, his neck countervailingly stretched at such an angle that he could just see past the resulting bulge, his left forearm swathed (we now noticed) in some sort of poster-board penlike stylus-cylinder thingie, which in turn got tucked into his beltline. Across all of which, having in the meantime developed the picture, Cummings had now sketched a mad series of Euclidean compass constructions in a sort of latter-day Vitruvian-man frenzy, beginning with the center of the circle whose circumference limned the perfect arc of his extended belly and thigh (and curiously, the exact folds of his pants right along his knee). Now, if you drew the diameter of that first circle parallel to the ground below (as he did), and then extended out from that center along that line toward the right, you came to a point where another line intersected that diameter, one which in turn rose up diagonally from that point through the artist’s elbow on up past the upper tip of his ear and then through the top of his head and beyond. Where that line intersected with his elbow, Cummings had drawn another horizontal line parallel to the diameter of the original circle below, from the elbow joint through the stylus thingamajig and past the beltline out into the space beyond that. Rising out from the point in the center, the eye as it were, of what would have been the ink-stylus (if it were in fact an ink stylus), he had limned the arc of another greater circle, one which traced a path between the horizontal line going past the beltline and the diagonal line coming out of the outstretched neck, two lines which in turn converged back there at the elbow joint at an angle of exactly 67 degrees. Ta-daah! But to what purpose? Who the hell knows. Except to notice perhaps that 67 divided by 90 is 0.744444, or almost exactly three-quarters; and 90 divided by 67 is 1.343 or almost exactly one-and-a-third. Hence perhaps the strange serene equilibrium of the whole madcap construct (an equilibrium in turn echoed in the line jutting out from the original center, parallel to the elbow-to-headtop diagonal, albeit jagged over a bit, which in turn carved out an inverse 67-degree arc on the lower right quadrant of that original smaller circle: Sorta like the drinking bird toy).

I don’t know, I just love this sort of thing. Or not love it exactly: rather I savor the experience of getting lost to myself and into such consuming perplexities (see that other chronicle of vertiginous, that time calendrical, captivation back in Issue 62, or for that matter my predilection for some of the similar sorts of crazed conceptual spinouts evinced by that other Pal of the Cabinet Walter Murch, as in Issues 5 and 33 and so forth).

All of which reminded me of another delicious gyre of an image, this one perpetrated by still another master of the neo-Euclidean sublime, the now octogenarian New York artist Robert Mangold who back in 1972 (right around the time Cummings may have been hazarding his own bulging profile back on the other coast) came up with this riddling masterpiece of a drawing:

Nothing to it: a simple circuit with a series of chords, one connecting to the next, a twelve-sided polygon circumnavigating the bounding circle. Except wait: look again. Because moving clockwise, the polygon slides from noon to one to two to three to four to five and down to six inside the circle and then from there through the remaining stations back up to noon outside the circle. What the…?

All of which came to mind the other day when I happened to be in LA (for the Robert Irwin memorial commemoration in the bowl of his garden at the Getty) and I dropped by Pace LA’s just-opened show counterposing the exquisitely measured work of the late Agnes Martin with that of an inspired young Polish-German surrealist named Alicja Kwade, one of whose pieces: well, see for yourself.

An ordinary everyday wall clock which rotates relentlessly counterclockwise around its own resolutely vertical second hand: tic-tic-tic-tic. Somewow managing in the process to turn time itself clean inside out.

Come to think of it (see a brief video of the ensuing dilirium here), it was the Kwade that reminded me of the Mangold which reminded me of the Cummings which in turn finally scratched the hankering itch occasioned by that stupid drawing of mine from two weeks back… So go figure.

* * *

The Main Event

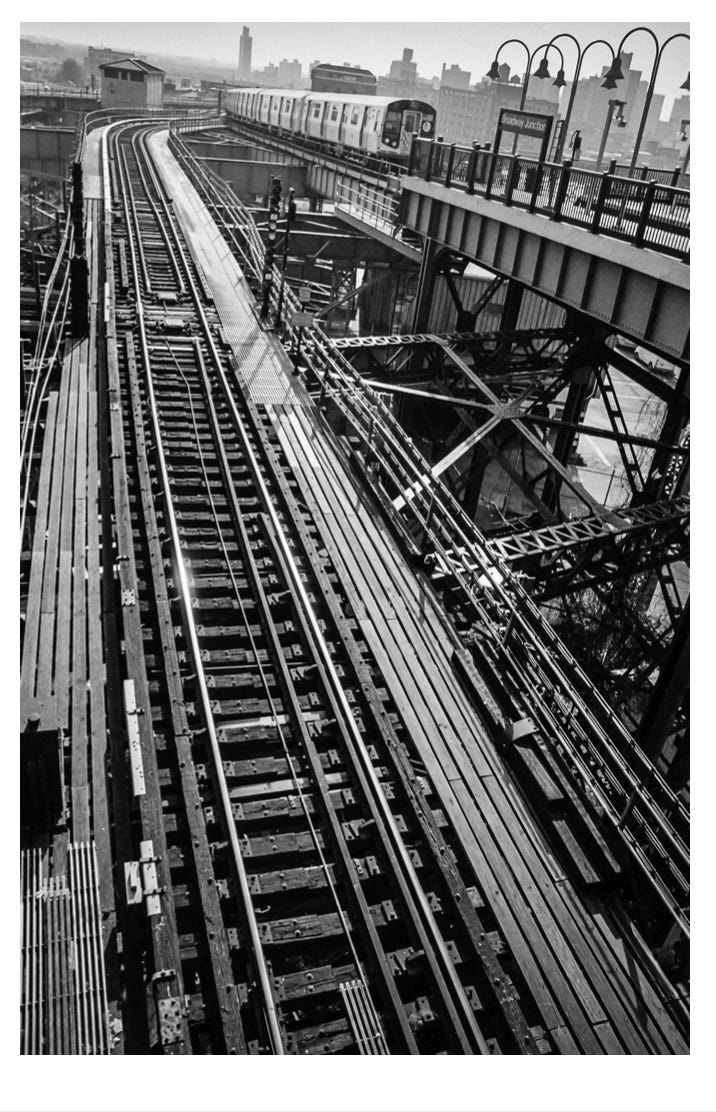

A DEEP DIVE INTO NEW YORK’S SUBWAYS

WITH ED HOTCHKISS

Ed Hotchkiss was born in Denver in 1956 and remained thereabouts in the middle of the country through college at the University of Colorado, which is hardly to say that he stayed put. Already by age 21 he’d hitchhiked through all 48 states in the mainland United States. After college he enrolled in the graduate business school at Columbia, somehow managing to get into International Student Housing (they must have been accepting aspirational globalists as well at the time), which is how it happened that, on a trip to the UN with one of his International Student friends, he met Khadija Musa, a fetchingly vivid Somali woman from Kenya who was working as a guide there at the time but would go on to a far-flung wide-ranging career in the UN system, and the two of them have been together, on and off, ever since. I say, “on and off” only in the sense that both would soon begin ranging wide and flunging far. Ed, in the meantime, having achieved his business degree and presently a CPA certification, had drifted into banking risk and credit management, moving from company to company, eventually culminating at AIG, where he served as chief credit officer in the international division for ten years. Which in turn is to say that he was being sent all over the world to scope out situations on the ground in country after country. Risk assessment isn’t only identifying downsides but also evaluating and celebrating treasures and ferreting out opportunities as well: looking and looking close. And in country after country, both on these business trips and across intervening vacations, he would make a point of scoping and valuing deeper and deeper into the backcountry, far off the beaten track, simply out of ever-dappling curiosity.

By now he has been to over 100 such countries, though he still hopes to have visited them all before he hangs up his backpack for good. “But what do you call a country?” he shoots back when I ask him how many more he has left to go. “The UN says there are 193, a number which includes the Vatican and Palestine, but not such nonvoting members as Taiwan and Kosovo. I’ve been picking up my game, in these my retirement years, though the recent Covid siege set me back a little. Still, I hope to visit them all, and not just visit but take the time to get a deep sense of each.” And you can follow his ongoing adventures and ever-widening insights in that regard on his utterly absorbing website.

*

The point here, though, in our present context, is that with Ed Hotchkiss, we have a world traveler who for the better part of his post-university life has been based in and around arguably the planet’s greatest and most teemingly various world city: New York. When he travels the world, to judge from his photo logs, he delights in landscape, but what he really loves doing is watching people (he’d likely agree with Auden: “To me Art is the human clay, / And landscape but a background to a torso; /All Cezanne’s apples I would give away / For one small Goya or a Daumier”)—people everywhere and in all their profuse and dazzlingly multifaceted specificity. And New York, for its part, is itself made up, precisely and maybe more so than any other city in the world, of people from all over the planet. “People talk about the United States as a melting pot,” he tells me, “but that’s not really the case. In New York, anyway, it’s more of a parfait, this profusion of specific national communities, but most of them concentrated in specific local neighborhoods.” He figures that each of the city’s five boroughs is in fact made up of approximately fifteen different such neighborhoods. And he has visited every single one. “But in the subway, which is how I get to them all,” he goes on to relate, “it really is a melting pot—the entire world in microcosm, all the communities tumbling and scrambling all over each other, as, by and large peaceably, they just keep going about their days. And getting to observe that in turn is one of the things that keeps drawing me down there.”

Like everybody else, trying to get from one place to another in the most efficient and affordable way, if not necessarily the most blithe and commodious, is what draws us all down there. But most folks, as Ed notes, downshift into a sort of stupefied autopilot the moment they ford the subway turnstyles: resolutely ear-podded, or eye-focused on their book or paper or magazine, or just plain trance-exhausted, they make a point, by and large, of not looking at each other. Hotchkiss, on the other hand, just can’t stop looking (it’s become a professional reflex, or else maybe it was a propensity in that regard that drew him into risk assessment in the first place)—looking and seeing!

Most of the photos that came to make up his 2022 book Station to Station, Ed tells me, were taken between 1996 and 2011, with the better part of those between 2000 and 2004—the very years, as he told me, when he was also serving as a village trustee and then the mayor of Pelham, the first suburb beyond the Bronx on the Long Island Sound side of far southern Westchester County. And this, too, is pertinent, for his interest in people has never been solely individual: he has always been interested in the dance between people and groups of people and groups of groups. In how places work. And what better place to observe such interactions, most often playing out almost unconsciously and unawares, than down there in the subway?

In the charming and vigorous reflections with which he ended his volume, Hotchkiss elucidated his method: how, in short, he managed to capture such a remarkably affecting sequence of moments, brimming as they are with such generously sly and wryly pitched fellow feeling. Henri Cartier Bresson, arguably one of the greatest street photographers of the last century, famously liked to speak of “the decisive moment,” but Hotchkiss makes it clear that as far as his own practice has been concerned, it’s always been more a question of steadying his gaze toward the ripening occasion. He snaps thousands of photos down there, but the real adventure, he’ll be the first to admit, comes when he returns from down those depths to his upside home where he quickly dives into that other tunnel, his darkroom, developing the negatives and poring over the proof sheets, studying and assessing as has been his lifelong wont, panning for epiphanic gold.

“We live our lives,” Sartre once observed, “as if we are telling ourselves a story, and we live surrounded by the stories of others.” At the end of the day, Hotchkiss is a master at evoking the bracing criss-cross of tales that comprises the churning lifeworld of the underground city.

And so, herewith, with Ed’s permission, a generous sampling from that tumbling trove:

And believe me, that’s only skimming the depth’s surface. If you want to see more, do get yourself the book here.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

Notes From Otherground, an Animal Mitchell Publication, 5 1/2 x 8 1/4, 20 pp., 1981.

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

you forgot the ENNEAGRAM, in the division of paradoxical circles. don't know it? you should.