WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

For something completely different, a case study in mathematical obsession keyed to this very day, February 29, 2024—followed by a Magritte/Einstein chaser.

***

From the Archive

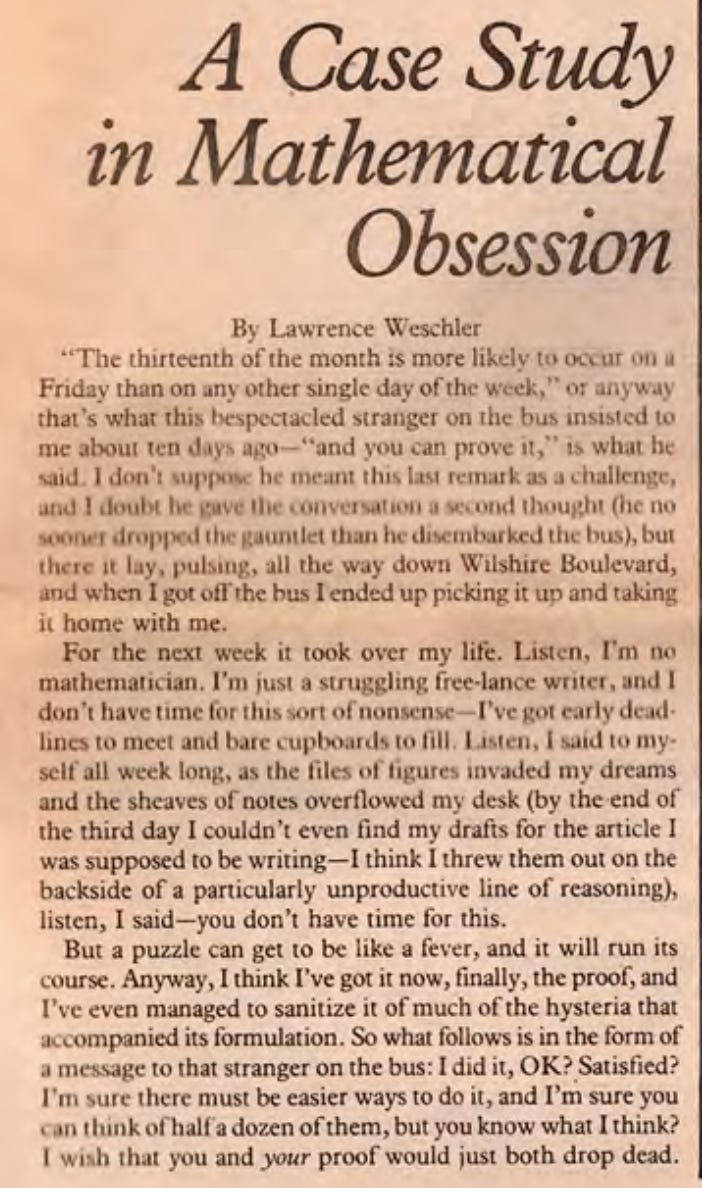

AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT

LA Reader, Friday, July 13, 1979

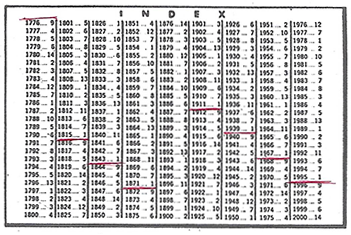

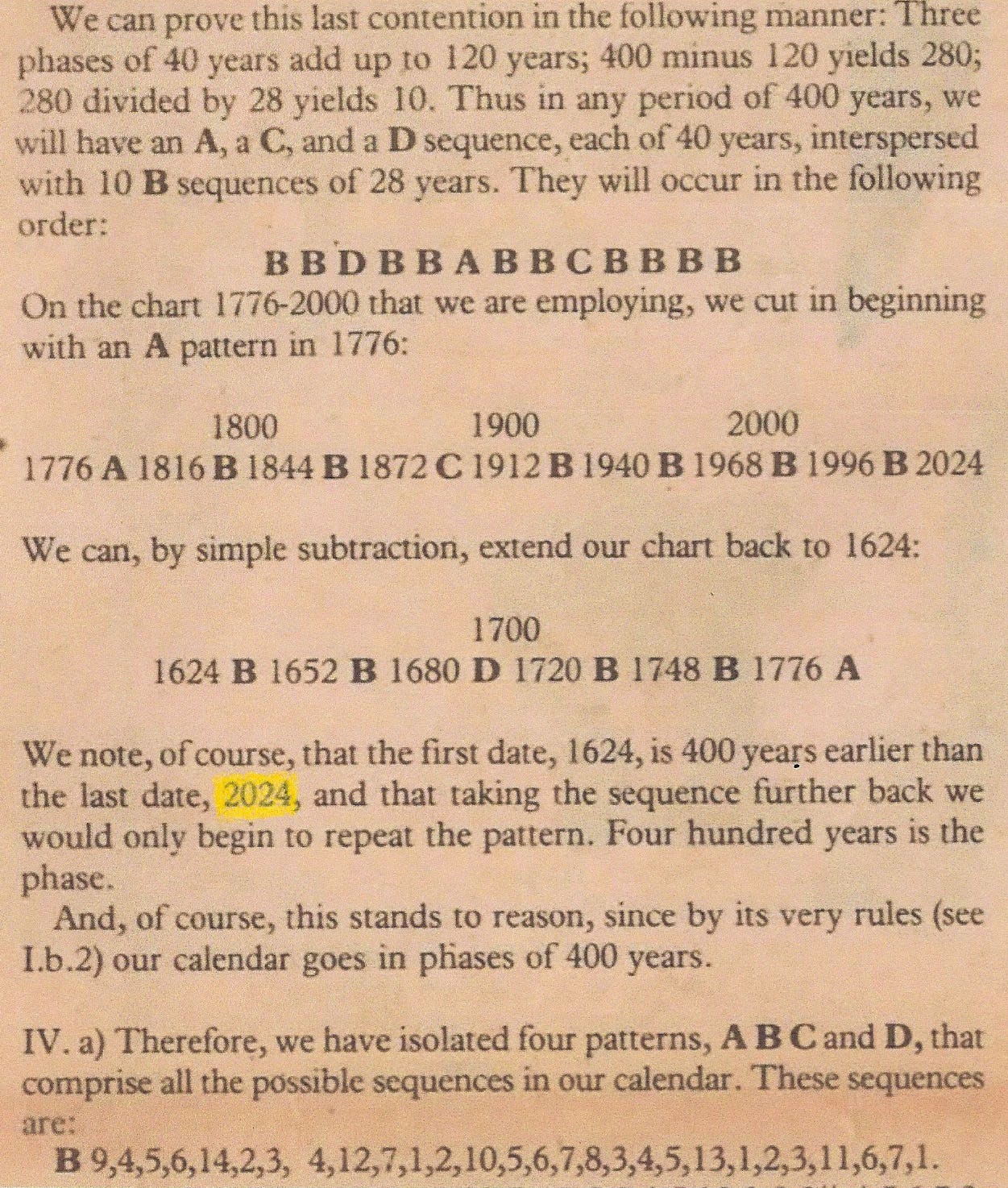

The last time I thought about any of this was on Friday, July 13, 1975, which is when I published the piece that follows (the account of a then-recent deep-dive into a quicksand conceptual rabbit’s hole) in the LA Reader, one of those freebie alternative newspapers bales of which used to get tossed onto the flanks of liquor stores all around town every Friday. Friday the thirteenth being the operative occasion, the law of leap-years being the pertinent premise, and (as I realized to my astonishment the other day upon diving back into the whole morass) today, this very day—February the 29th, 2024—constituting the bounding limit of the ensuing cogitation. All of it, I grant you, a touch insane. But make of it what you will, or not.

*

POSTSCRIPT

Actually, no, come to think of it, there had been one other time that I had given this whole comic-manic misadventure a bit more thought, which happened to have come about four years after the Reader’s publication of the piece. By that time I’d moved up a bit in the world and (on the basis of a profile of Robert Irwin tossed pretty much over the transom) secured a job as a staff writer at the New Yorker. The Irwin piece had run, alongside a good deal of reporting from Poland, a profile of the Louisiana Museum in Denmark, and the chronicle of the rediscovery of a long bypassed first-generation abstract expressionist by a relentless young bounder from India, and the magazine’s legendary editor William Shawn had called me into his office

to ask if I had any other topics I might now like to pursue. “Time!” I blurted out, whereupon the sage editor’s brow curdled. “The magazine?” he queried, anxiously. Oh no, no, I clarified: Clocktime!—why was it divided into sixty seconds and sixty minutes but then 24 hours—and calendar time, why twelve months of such varying numbers of days, and why leap years, and while we were at it, whence time zones and international datelines and the like? Mr Shawn’s face immediately brightened and he acknowledged that that might indeed constitute a good subject for exploration. He reached for his notepad and penciled in, in his faint feathery hand, the phrase, “Mr Weschler: time,” which was as much as to say that the topic was hereafter reserved for me, I could draw on the magazine account for any attendant expenses, and he would expect to hear from me again whenever I had completed the piece in question.

And off I went, beavering away for the next six months, researching the subject far and wide, but just as I was getting set to sit down and write, my office phone suddenly rang. “Hello, Mr. Weschler,” came the achingly (deceptively) meek voice, “Shawn here, Mr Weschler. I am afraid I have some bad news. Because I happened to be doing some reading last evening when I came upon the fact that international conference that established time zones and the date line and the whole meridian system took place in October 1884…” I know, I know, I interjected, I’d uncovered all sorts of juicy details about the event, and started relating a few of them: how for example the country-by-country vote establishing the longitude line running through the Greenwich observatory outside London as everyone’s degree 0 had gone 22 to 1, that one (of course) being France which insisted on listing an observatory outside Paris as their degree 0,

a state of affairs which thereupon persisted on all French maps of everywhere on Earth through the outset of the First World War! Mr. Shawn waited out my blast of enthusiasm before intoning, “Well, yes, but I’m sure you can see the obvious problem.” From my silence I gather that he gathered that actually I could not. “Well,” he patiently elaborated, as if explaining the simple self-evident facts of life to a ten year old, “that means that this coming year will mark the centennial of that conference”—he waited a moment for the penny to drop in my demeanor, but when it became clear that it hadn’t, he sighed and continued—"and we make it a policy here at the magazine not to observe or engage with such anniversaries in any way. So I’m afraid we will have to pass on your piece after all. My apologies again, I hope you understand.” Phone click, end of conversation, end of piece.

Which is how things sometimes went there on West 43rd Street. In the end, though, I was able to salvage a single line of speculation from all that research for deployment in a little piece of sidebar commentary in a November 1992 issue of the magazine on the occasion of the last weeks of a visiting Magritte show, which I in turn folded a few years thereafter into my eventual compendium Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences. To wit:

MAGRITTE STANDARD TIME

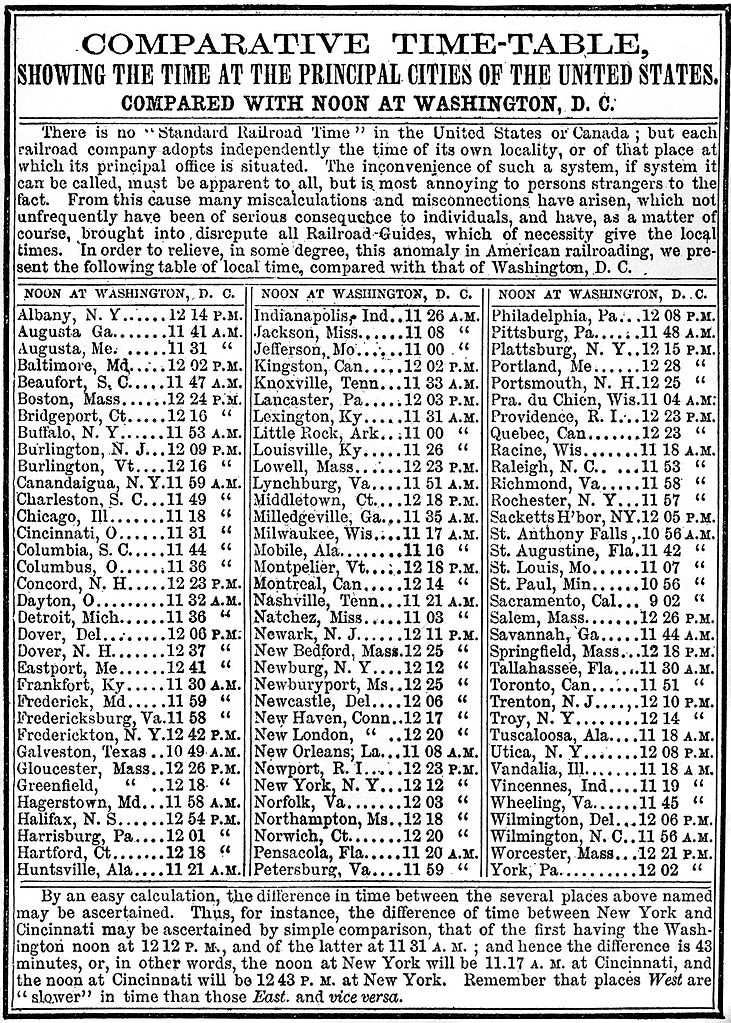

In olden days, time was true. Noon occurred in every village at the very moment that the sun reached its zenith over the courthouse steeple. Trains—in particular, transcontinental rail travel—changed all that. In the era before time zones, passengers on coast-to-coast trips might well have had to jimmy their watches dozens of times, adjusting to the separate temporal reality of each locality through which they traveled. (Schedules were similarly scrambled; New York City’s noon being Buffalo’s 11:40.)

For years, people puzzled over these mysteries and muddled through the confusion—what did it mean, for instance, to say that two events happened at the same time in two different locations?—until, in 1884, an international conference finally resolved the problem by decreeing a unified system of standardized time zones.

Is it any wonder that a genius, born in 1879 and growing up in a world grappling with these issues, would go on to formulate a theory of relativity which deployed trains as one of the principal motifs in its exploration of simultaneity? (“Lightning has struck the rails on our railway embankment at two places A and B far distant from each other…”) And is it any wonder that, a generation later, a leading Surrealist painter would have recourse to the same train motif in his 1938 painting Time Transfixed (La durée poignardée)?

But what of this coincidence? René Magritte was born in 1898 in Lessines, Belgium. The train pictured in the photograph on the right overshot the Gare Montparnasse, in Paris, on October 22, 1895 (perhaps owing to some confusion in the train-in-question’s cockpit as to which meridian—Greenwich’s or Paris’s—the train’s operators happened to be using). Surely, at any rate, no relation between the photograph and the subsequent painting. Except that it was Magritte himself who gave us to understand that everything is relative and everything is simultaneous.

Always has been. Always will be.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

I was cleaning out some backfiles the other day and came up on this Letters to the Editor exchange that erupted immediately after the original publication of the "Chances are it's Friday the 13th" piece in the LA Reader. The initiating correspondent is Ray Weschler, my brother, of subsequent Berkeley softball fame (see Cabinet #20), at the time a preternaturally pesky fifteen years old. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1yEYk19EzBSbV-9f8gfLzbjBNgA14QBV_/view?usp=sharing

Meanwhile, why not notice how Sunday is stealing the limelight as we turn to March? The last four Sundays in March (10, 17, 24 and 31) are hosting in order: the start of Daylight Savings Time, St. Patrick's Day, Purim (these last two holidays are closely linked in calendar closeness and raucous spirit), and Easter. Easter in March? The Jewish calendar is celebrating its own Leap Year by repeating a month (Adar 2, starting on March II). As a result, while Easter is "early", Passover this year will end "late" - on the last day of April.

And while the solar Gregorian and the lunar Jewish calendars leap in different ways, in this decade they are linked digitally: from January through August beginning in 2020, the digits of the Jewish year add up to the last two digits of our secular calendar, as in this year: 5+7+ 8 + 4 = 24. After five years (5790 and 2030), that coincidence will disappear for a long time.