WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This time out, we’ll start with a reader resonating powerfully off that Tadeusz Różewicz poem from a few issues back. Then, on the occasion of the release of his first fiction, Ubi Sunt, a conversation with digital magus Blaise Agüera y Arcas on the current state and future prospects of machine learning and consciousness. And we’ll wrap things up with a deep dive into another small concentrated masterpiece by our new friend, the great nineteenth-century Prussian painter Adolphe (that toe!) Menzel…

* * *

REPRISE

A playwright-director friend of mine sent the Polish master Tadeusz Różewicz’s 1946 poem, “In the Middle of Life,” that I’d included a few issues back (#15) as part of that trill of selections about trying to determine the true name for things in Ukraine, to a friend of his, the veteran voice actor Peter Beckman (whom the gamers among you may know, for example, from his signature turns in the Final Fantasy series). “The instant I finished reading Różewicz’s poem,” Beckman subsequently reported, “I felt uncommonly close to it, as though the poet had peered into my soul when composing; I knew that I had lived it, and that I must interpret it; I cannot recall when a poem has affected me as much. The next day I tried recording a few takes, but they all ended in tears. Then came the one I am enclosing, the right one. Do with it what you will.”

And so I pass along Beckman’s effort (testimony both to his own extraordinary voice and to his refined sensibility) to the rest of you. I only wish that Różewicz himself, who died in 2014, could have heard it, and for that matter that Ukrainians and maybe even more importantly Russians might yet hear it today. Even across the various linguistic and temporal expanses, Beckman’s channeling of Różewicz’s devastating lyric packs a heartrending wollop.

Have a listen here.

* * *

This Issue’s Main Event:

A Conversation with Blaise Agüera y Arcas

(Part One of three)

Variously hailed as “one of the most creative people in the business” (Fast Company) and among “the top innovators in the world” (MIT Technology Review), Blaise Agüera y Arcas is an eminent software designer and engineer; a world authority on computer vision, digital mapping, and computational photography; and, ever since his much-noted departure from Microsoft to Google in 2013, one of the leaders of the latter’s machine learning efforts.

As it happens (long story), Blaise and I have long considered one another among each other’s best friends, which is odd (and exciting) in that we seem to keep fundamentally disagreeing on utterly fundamental issues. Not that we aren’t without even greater and overriding sympathetic alignments. But with the coming publication of Ubi Sunt, Blaise’s first novella (and now, on top of everything else, he’s a ficcionario!)—an incredibly packed apologia pro vita sua (or, at any rate, somebody’s, or something’s, vita sua)—it seemed like this might be a good opportunity to introduce Blaise to those of you who may not already know of him (those of you who do will need no further enticements), beginning with a sense of the life that led into such an extraordinarily polymathic career.

LAWRENCE WESCHLER: To begin with, Ubi Sunt is a text that you recently composed during COVID time, a sort of novella. And there seems to be, at least at the outset of this tale, a narrative voice that is kind of a person like you, who seems to be living a life kind of like yours. But since, of course, we can't claim anything about you just because your narrator behaves in any particular way, why don't we start with you yourself? Why don’t you give us a little potted history of who you are, leading eventually perhaps to how you came to write this book and how you might relate to this narrator, but just starting with your name and where were you born, who your parents were, all that kind of stuff, and then take us through your education and so forth— I'm talking like five minutes or so.

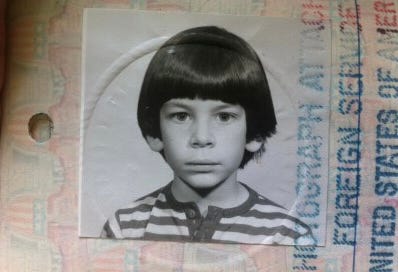

BLAISE AGÜERA Y ARCAS: Okay, so the brief CV: I'm Blaise Agüera y Arcas, and I was born in Providence, Rhode Island. My mother is Jewish girl from Baltimore. My father is Catalan. They met on a kibbutz in Israel and then moved to the US in the early 1970s. I was born in 1975 and only lived in the US for eleven months before we all moved to Mexico City, and that was where I grew up. They moved there because, as far as I understand, my father wanted to become a doctor and he was a little old to be accepted by any American medical school. And so he managed to wrangle his way into the Politécnico in Mexico City, where he was older than everybody else by a factor of something. So he did his MD there, and his internship and his residency, and then there’s this social service where you kind of pay the state back for your education. And then we all moved back to the US.

LW: How old were you?

BAA: About ten.

LW: What kind of kid were you before that?

BAA: Very, very shy: a strange one. Older kids called me R2D2. I was hard to understand. I was quite socially isolated and got picked on a lot. I got on better with adults than with kids my own age. I hung out quite a bit with my mother's high school art students. She was teaching studio art at the at the American School in Mexico City.

My linguistic story was a little odd as well. I grew up bilingual: I read a lot in English but my conversation was mostly in Spanish. By the time we moved to the US, I had a strange accent in English. I had a large vocabulary mostly acquired by reading a lot of science fiction. And none of the pronunciations matched anything that any actual English speaker would use. So my general social malaise and isolation and alienation continued in the US.

LW: And were you mathematically inclined or not especially? What kinds of things were you doing there where I would say, Oh, I'm not surprised he turned out to be doing the sorts of things you would be doing.

BAA: You wouldn’t be surprised probably. I wasn't very mathematically inclined early on, but I was very electronics and computer inclined. My parents got me a computer when I was six. This was in 1981 and it was quite early days for this sort of thing.

LW: Was it a Compaq or one of those sorts of things?

BAA: The very first one was a TI 99 4A with 16K of memory, and a cartridge port. I used to think that “a partridge in a pear tree” was “a cartridge in a pear tree”, because I had no idea what a partridge was. I became obsessed with programming, would memorize technical manuals and apparently ran up an enormous phone bill calling Texas Instruments in the US to get detailed technical specs to various things. And I hung out quite a lot with the electronics repair guy on the ground floor of our building: he repaired radios, TVs and VCRs. I loved to take things apart, and spent lots of time in the junkyard. I think when I was three, I took apart everything in the house that could be taken apart, except for the TV, which was too big for me to move.

LW: How was that received by your parents?

BAA: I was terrified. Because I mean, first I’d unscrewed everything, taken everything apart, but I still couldn't understand how it worked. So then I began to take apart the individual transistors and resistors and so on. There's no coming back from that sort of disassembly. And I perseverated, I did this with everything. I’d written this very crude sign for the door, “Experiments in Progress, Nobody can come in,” and I was trying to hide everything under the bed and in the closet and so on, and it was a lot of stuff, we're talking literally everything in the house.

Of course, they discovered it, I have no idea how I was expecting that that wouldn't happen. But they were really kind, which was a shock, since I was sure I was in really deep shit. They were really kind and they didn't yell and they essentially just ensured that I had a steady supply of things from the junkyard to keep my needs met.

LW: Were you aware of any other kids who were doing this kind of thing? Did you have any sidekicks, or you were completely by yourself?

BAA: No, completely solitary. Well, once— we visited the US in the summers sometimes, and I had a cousin living here. We each got an old typewriter to keep us entertained while the adults were doing whatever they do. I was delighted with my typewriter and began taking it apart, whereas my cousin took a hammer and began hammering on his. I was so horrified and judgmental. I essentially never spoke to him again: how could anyone do that sort of thing?

LW: So, okay, you've come to the United States, and you continue to be this way. And you're now in junior high and high school. And how's that?

BAA: Awful. I had an awful time.

LW: Where were you by the way?

BAA: This is Maryland. In the first couple of years, we moved in with my grandfather in something like a retirement village for old Jewish people just outside of Baltimore. It was the five of us— my parents, my younger sister and me, and my grandfather— in a two-room apartment for a couple of years. There was nothing left to take apart at that point. I do remember pilfering watches that had radium in the dial and in the darkened bathroom shaving off all of the radium so as to make a pile. I was trying to collect radioactive materials.

LW: As one does.

BAA: As one does. (laughter)

LW: Meanwhile, in school, you are socially awkward?

BAA: Socially awkward, incredibly irresponsible as well, a very poor student. Very dodgy performance at school, often did not do my homework, was often reading under the table. And I spent a whole lot of time on my computer, doing things like reverse engineering video games, breaking the copy protection on them, dialing into semi-illicit bulletin boards, which were the sort of proto-internet, over the phone lines, and things like this.

LW: And did you have any teachers who recognized that you might be a cool kid but just having a difficult time, or did everybody just think you were weird?

BAA: Yeah, there were. I mean, everybody has their little handful of teachers who sort of see them, right? Who understand them. And I had a few who were who were cool. There was one who, in eighth grade, taught civil liberties, and that was quite a special thing. And then in high school, I ended up going to the private high school where my mother was a teacher. It was tiny: I was in a class of sixteen other students in my grade, which, on the face of it, was a terrible idea. But actually, high school was a time of coming into my own socially.

LW: And socially, are you beginning to have girlfriends or whatever, at that point, or not especially?

BAA: Yeah, about halfway through high school.

LW: And age-appropriate?

BAA: Yeah, at least that's what I'm going to say in this recording. (mutual laughter) But yeah, I went to an astrophysics camp…

LW: As one does.

BAA: As one does. Well, there were these programs where the government uses standardized testing to try and recruit the young into the military industrial complex. And I did many of those. That’s how I ended up working at the NSA as a kind of kid cryptographer, or whatever. And at the David Taylor Naval Ship Research and Development Center, where I helped reprogram the guidance software for aircraft carriers to improve their stability at sea so as to reduce sea sickness among sailors. And in the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab. So I sort of began my career in industry, I suppose, doing math and programming for the government, and did that sporadically for a few years. That was happening from, say, 14 to 19.

LW: So how do you get from that to Princeton?

BAA: Well, by high school, when grades began to finally matter, I guess I did well enough, despite my poor study skills, to have a good official record. And I had done a lot of extracurricular stuff as well: the things that I was just talking about. I also really loved literature and writing, and the humanities generally. My mother was teaching art history at that point and I took several art history classes from her in high school. It could have been awful, but she was actually a great teacher. She also taught film: I took film and AP film from her, and studio art, too. So my CV looked solid by the time I graduated high school, and, and I had a really easy time getting into great universities. I got in just about everywhere. But I chose Princeton—I’m sorry, we've exceeded the five minutes, so I'll try and speed up.

I nearly crashed and burned in college. I went in wanting to study physics. I wanted to become a theoretical physicist. I wanted to be Feynman, basically. I had quite a negative opinion of all of this computer stuff I'd been doing: it seemed to me like just playing around. I really wanted to get at the fundamental fabric of the universe. I was so snotty about it. So I took a lot of physics, and I took a lot of wonderful humanities classes as well. That was where I met Tony {Anthony} Grafton, who, in turn, introduced me in a very roundabout way to you (one of the required readings in the very first class I took from him was your Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder). I loved his courses, though I also had a near death experience with the first one I took, academically speaking.

I don't know if I ever told you this, but I was on academic probation at some point because I had managed to get three D's in a single semester, because I was so bad at doing my homework. And Tony gave me an F in his course on Magic and the Renaissance. Because most of the grade was based on a final paper. And when the due date came, I was really into that paper and I was just continuing to write. I'm writing, the grades are due, I'm writing, the various deadlines are passing, I keep writing. And finally, I look up from my writing, and I have a giant 90-page essay on Da Vinci's embryological drawings, and I brought it to Grafton. And he said, “But I've already failed you from the class.” (laughter) But then, as I’m standing there, he reads it. And of course, he reads very, very fast. So he goes and goes and goes and goes, and finally he says, “Well, I think we should change your grade.” And we wandered around campus from his office to the registrar's office, and administration, and finally managed to get the grade changed from an F to an A, or an A plus, I can't remember. And that rescued me and allowed me to live to fight another day at Princeton.

LW: When you say that you almost crashed out, what was that about, do you think?

BAA: (heavy sigh) It was a combination of things. Some of it was my own lack of discipline. I’d never really had to develop study skills, and I could sort of bluster my way through in high school. At university, I was taking the hardest classes that I could, and, you know, it was physically impossible to bluster your way through accelerated Chinese and particle physics and calculus on manifolds, and my habits were not adequate to it. Also, I was depressed. Because I had been looking forward to finally finding my people. And the undergraduates at Princeton… it kind of wasn't what I had thought it would be. I was disillusioned at the thought that there was no other place to go next, that this was the end of the line.

LW: My memory of Princeton when I was teaching there, not that long before this, was that you also had the whole beer culture.

BAA: Yeah. It was awful.

LW: But are you changing from physics to Computer Science at that point, or…?

BAA: No, I did graduate in physics. But toward the end of this period… well, these stories are long and complicated, but I did take a year off between my third and fourth years, and ended up hearing through a friend about this startup working on 3D on the Web that a professor in the physics department, Sasha Migdal, was launching. It was 1996, and of course, making an internet startup was the thing to do. So I joined this little gang of Russians and hammered away at the startup game. By three quarters of the way through the year, we were traveling all around the world, I was giving these presentations to the board of Sony in Tokyo, and all kinds of stuff like that. And before the year was out, the company had gotten acquired by a larger software company in California, and I had been living the big fancy life, I’d bought a BMW and so on, on my enormous salary of like $70,000, which was inconceivably much money to me at the time. So of course by the time September rolled around, I was $40,000 in debt. And naturally had not gotten any piece of this company when it had gotten sold. I was going back to school (laughter) poorer and wiser.

But I did have a sort of insight, I suppose. I realized that all this computer stuff was not just a distraction, or something to be ashamed of. Because originally, as I was saying, I’d thought that fundamental physics was the way to go. But I began realizing that when it came to the big mysteries, the brain was way up there. And if studying the brain is really where it’s at, then computation and knowing how to program and being able to use the tools of Applied Math would be really valuable. So I started trying to integrate my desire to understand fundamentals with the skills where I had fluency. And that was very exciting. It also seemed to me that the computer is like this telescope or microscope that could let me explore all sorts of things that have not really been studied this way before. That’s how I got into the early printing project that you know all about.

LW: Let’s slow down there for a minute. So this is your senior year at Princeton, you're still going to graduate in physics, but you're doing more computer stuff, and by way of Tony Grafton and Paul Needham at the university’s Rare Books Library, you suddenly find yourself putting your computational chops to work delving deep into the pre-Gutenbergian, incunabula origins of the printing press?

BAA: Yeah. It turns out the first-ever font is not the one that was used to print the Gutenberg Bible, but rather a somewhat larger font that's similar. Gutenberg had used it to print some earlier work, probably in the 1440s. The earliest one, as far as we know, is the Sibyllenbuch fragment, this apocalyptic German poem that only survives because a copy was pasted into the boards of a later book.

LW: Amazing how you get this huge positivist technological breakthrough and among the first things that emerge are these primordial atavistic ravings.

BAA: Yeah.

LW: Just like today!

BAA: Indeed. But so the earliest font survives accidentally in this weird fragment. After the Bible, this same font was used to print a few other surviving texts too. The challenge was: can we take these texts, image all of the letters, and figure out what the actual original shapes were of each letter in the font? I mean, a font is not just a handwriting style: it's the idea of each letter being a unique shape, cast from an identical mold. But we found out that the shapes of Gutenberg’s letters were all different. Each lowercase “a” is unique, as if it had been written by hand, though it was still a piece of movable type— meaning it got reused in later pages. It looked like each piece of type had been cast from a temporary mold, made by pressing tools into sand or clay almost the way a scribe would write the strokes. That made all the letters unique, so there was no font! Gutenberg’s technology was kind of neither this nor that, it was in between.

LW: You'll forgive my rampant free associative tendencies and proclivities, but that's just what Ubi Sunt is about, too. It's basically about the early stages of hand-made consciousness or language, as it were, which is kind of this, but it's not quite that.

BAA: Yes, that's true. It's origin stories. And, yeah, origin stories often don’t work the way people imagine they do. So in the case of printing, everybody assumes that printing was invented by Gutenberg, and that's it: that was the whole story. Whereas the real story of the first fifty years of printing was extremely complex. It involved a Cambrian explosion of different sorts of technologies that only settled into what we understand to be printing sometime around 1500.

LW: And again, the Ubi Sunt moment is also a sort of Cambrian explosion of possibilities.

BAA: Yes, exactly.

LW: So, okay, now let’s try to do the rest of your life in just five minutes, how we get you from there through Seadragon and Photosynth and on to Microsoft and after that to Google.

BAA: Okay. So, in the process of doing all of this analysis of printing, I needed to analyze very, very large digital images— there were hundreds of megapixels per page— because I wanted to get all of the details of every letter. Even opening one of those files was impossible, using most software available at the time. So I wrote my own, and the software I wrote to deal in an efficient way with all of these gigantic images struck me as interesting in its own right. I thought that if everything worked in the very fluid efficient way my new software did, the whole computing experience would be very different. You'd never wait for anything, ever. And you could handle arbitrary numbers of objects at once. That was how Seadragon was born. I wanted to change the way operating systems worked, the way they represented data, not only pictures, but documents of any sort. So I founded a little startup and did for myself what Sasha had done in the startup that I had helped him with. I got some angel investment from the east coast.

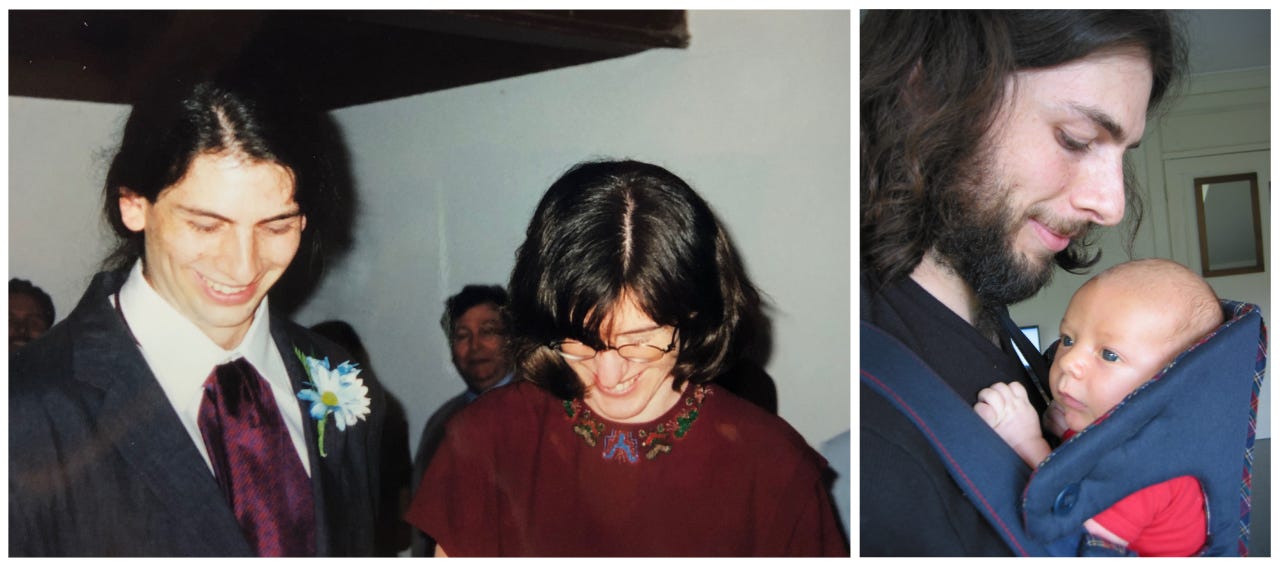

In the meantime, I had met and married Adrienne [Fairhall]. She’s a computational neuroscientist. We actually met via my advisor for my senior project in computational neuroscience. She began doing a postdoc with him just as I was finishing my undergrad.

LW: So your senior project was in Physics or in Information Science?

BAA: Both, and Biology as well. It was in the computational properties of single neurons.

LW: So you met her and you two are together.

BAA: So we're together, we have our first kid, Anselm, I'm starting up Seadragon, and she gets an appointment at the University of Washington. We ended up moving from Princeton to the west coast, to Seattle. And she starts as a professor at UW. I finished getting the investment for Seadragon here in Seattle and started up the company. It went really well, and a couple of years later, we got acquired by Microsoft.

LW: And Photosynth is what to that? Photosynth is something that uses Seadragon?

BAA: As far as Photosynth goes, with the help of some of my new colleagues at Microsoft and their UW collaborators, including Steve Seitz, Rick Szelski, and Noah Snavely, we were able to combine Seadragon with these really cool computer vision techniques that could piece together photos on FlickR related to a single identifiable tourist site, say, Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, use those to automatically build up an immensely rich, crowdsourced 3D model of the structure in question, which the user in turn could navigate around. All of which I discussed in my first TED Talk.

Blaise’s March 2007 TED talk. (If you haven’t already watched this, trust us: do so!)

LW: That’s the TED talk where you said that you never thought you were going to end up at Microsoft, and you're kind of amazed that it's cool, and so forth. So you're there for a while, and what sorts of things were you doing there?

BAA: I was there for seven years. And my efforts at changing Windows in sort of fundamental ways failed— that did not happen. But I did help Gary Flake to start up an organization called Live Labs, which was designed to sit halfway between Microsoft Research, which was much more academic, and the product half of Microsoft—the idea being, can we mobilize researchers who are really interested in applying their stuff to real life as opposed to just publishing papers? And can we marry that with serious engineering muscle and make interesting things happen? I would say that Live Labs was a mixed bag: there were some successes, there were quite a few failures. It was a great school for me in a way. Looking back on that time, I learned a lot about how to marry research with scale and with things that actually matter out there in the world.

LW: And what are some of the successes that came out of that?

BAA: Ooof.

LW: Okay, never mind. So how do you then get to Google?

BAA: Well, by 2012 or 2013, it had become clear that two things were going on. One was that neuroscience and computer science were reconverging, which was very exciting to me, because I see these as disciplines that were in many ways separated at birth, in the early 1940s. Because in the beginning, the enterprise of building computers was computational neuroscience. Computers were very, very closely coupled with our then-understanding of brains and how they work. The idea was to make artificial brains.

LW: That goes back to the ongoing vision of the brain as congruent with whatever’s on the cutting edge of technology at any given moment: how when telephones were the new thing, brains were likened to telephonic exchanges, and so forth.

BAA: Well, right: the metaphor we use for the brain being whatever technology is hot at the time. But there was more than just metaphor going on in this instance. At the start of the 20th century, there was this idea that reason was calculable, that what we did in our brains was about logical propositions and so on. And this goes back to universal language kinds of ideas that Cassirer and Heidegger and Walter Benjamin had been working on, and also to the work of Bertrand Russell and friends on the logical foundations of math. All of that led to this paper that that Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts wrote in 1943, called something like, “A logical calculus of the ideas...” It was a very pretentious title. Here we go. I've actually got it right here… (reaches for the paper)

LW: As one does. (laughter)

BAA: Yes, here we go. 1943. “A Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity.” And the premise was that neurons calculate Boolean functions, logical operations on predicates. So our brains are just giant circuits of logic gates, reasoning using this calculus of logical predicates. There are drawings of neural nets in the Logical Calculus paper that look exactly like logic diagrams with logic gates. But over the next few years, it turned out that brains don't work anything like that. Still, this became the big seminal paper of modern digital computing. So today’s computers do work this way. McCulloch and Pitts thought they had understood the brain, but they ended up inventing the computer instead.

LW: But now you’re saying they (which is to say the workings of computers and those of the brain) are coming back together after all.

BAA: They’re coming back together because of what began being called Deep Learning. Neural nets aren’t logical circuits, but they really can do the sorts of intellectual tasks that had long eluded computer science and the symbolic AI approach that dominated throughout most of the period from the forties…

LW: For the idiots in the room, like me, a neural net is what?

BAA: A neural net is a construct wherein you have a bunch of artificial neurons that are wired together in a network that goes from an input to an output, with many layers in between. Every individual neuron does something very simple: it takes all of its inputs from neurons in the previous layer, sums them all up in weighted proportions, and then applies an operator of some kind— it might be as simple as a threshold— to that sum, and then passes that result on to a neuron in the next layer. Real neurons do something a little bit similar to this, though they’re a lot more complex. But anyway, it turns out that just the weights, how much every neuron affects every downstream one, can define an arbitrary function from the input to the output. There could be many layers, so it may be a lot of weights.

LW: And that is the “depth” of Deep Learning.

BAA: Yeah, that's all Deep Learning is. The thing is that when we say arbitrary function, we really mean arbitrary function. The inputs of this function could be the pixels of an image, and the outputs could be “Is this a dog, cat, or alligator?” The idea that we could actually evaluate such a function seemed like science fiction in the eighties, or even the nineties. But that started to become real in the 2000s.

LW: So Google is working on that and they invite you to come along, or what?

BAA: Google was at the forefront of this whole deep neural net revolution at the time, and still is, I think. So I knew that I wanted to go there and be a part of that reconvergence. And when I say “reconvergence”, I mean that computers suddenly started to look more like actual brains!

LW: But what begins to swim into focus here, for me anyway, is whether the brain /mind problem as it applies to brains also conceivably applies to computers.

BAA: Yes. I like John Haugeland’s idea that maybe “artificial” is not the right word to use for the sort of intelligence neural nets are starting to exhibit now. Rather, one might use the metaphor of diamonds: there are artificial diamonds, and there are synthetic diamonds.

LW: Just today there was a headline that one of the main diamond concerns is no longer going to sell mined diamonds…

BAA: Which is great: that's as it should be. Now, of course, if they're not going to use mined diamonds, they’ll have two choices. One is to use glass or quartz, or something else dressed up as a diamond. So that's an artificial diamond. And the other choice is a synthetic diamond, which is a real diamond but grown in the lab rather than mined. Right? A synthetic diamond is perfectly real. It just has a different origin story, if you like.

LW: And how does that relate to artificial intelligence?

BAA: Well, you can say that something like the ELIZA program is an artificial intelligence. This is a program based on old fashioned natural language processing that pretends to be a Rogerian psychiatrist and just asks you questions about the last thing you wrote and sort of strings you along. It's based on a script, so I think it would be fair to say there's nobody home there. So that's an artificial intelligence in the sense that it spoofs being intelligent the same way a paste diamond pretends or spoofs being a real diamond. Most people would agree that a modern neural net-based chatbot is still not a person. But I’d also say it's no longer fair to say that it's a paste diamond. I think that there is real intelligence there. The way it's built starts to have similarities with the way it's built in our own minds.

LW: In our own minds as opposed to our own brains, or is that not a distinction for you?

BAA: For me, it's not a distinction. This is a place, I know, Ren, where you and I probably differ.

LW: You bet we do.

BAA: But I’m a hardcore materialist in the sense that if you do computational neuroscience, the premise is that the fact that our brains work using certain specific proteins and ion channels and so on isn’t necessarily fundamental. It could be a different set of proteins. Or, if you changed the basis to silicon, in principle, you could do the same thing.

LW: And this reminds me of one of my own favorite moments from all of my moments with you over the years at that panel I’d organized in conjunction with the David Hockney “Wider Vantages are Needed Now” show at the DeYoung in San Francisco in 2013.

The “Views from the Digital World” session at the “David Hockney: Wider Vantages Are Needed Now” Symposium at the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco, 2013. (My conversation with Blaise Agüera y Arcas, Alvy Ray Smith, and Peter Norving.) The Crisis in our conversation occurs at 16:19.

How I’d been waxing on and on about my hero, the late medieval diplomat, philosopher, mathematician, archbishop of Cologne, etc., Nicolas of Cusa, author of a book with one of my favorite titles ever, Learned Ignorance. He was a neoPlatonist, whether he realized it or not, and at one point he arrayed himself as opposed to St. Thomas from a few generations earlier, who was of course an Aristotelian, over the question of the best way to attain knowledge of God. Thomas and his followers basically argued— granted, I’m oversimplifying here— that one of the main ways to get to God was by way of his Creation, by meticulously cataloguing all the marvels of all Creation in as systematic a way possible. To which Cusa countered with the analogy of a n-sided regular polygon inscribed inside a circle. So you started with an equilateral triangle inside the circle, and you added a side and you had a square, and another side and you had a pentagon, and so on, until eventually, with say a million sides, you began to approach something that was beginning to look more and more like the circle, which in this analogy represented true knowledge of God. But Cusa observed how, on the contrary, the more sides you added the farther away you got from the circle, because now you had something with a million sides, whereas a circle has only one, and with a million angles whereas a circle has none.

No, Cusa counseled, at some point you were going to have to make the leap from the chord to the arc, the “leap of faith” as he called it (Kierkegaard got the phrase from him), a leap that could only be achieved by way of grace, which is to say for free. And that image has always struck me as immensely powerful in all sorts of contexts, working equally well if you strip it of its specifically religious context. As a way of talking about the brain and the mind, for instance— how no matter how detailed a picture you get of the brain, and that picture is getting more and more magnificently detailed every single day, you will still never be able to account for the miracle of consciousness through that route alone. There is all that, and something more…

So I was yammering on like that, at which point you leaned over, sotto voce, and asked me, “Ren, you are a materialist, aren’t you?” and I replied, equally sotto voce, “Actually, no, I don’t think I am.”

BAA: Yes, that was when I knew that we had an important difference.

LW: You looked completely abashed and you just kept looking at me for the rest of the panel as if I had sprouted a horn on the top of my head. (laughter)

BAA: Well, you had in a way in that moment. Yes. (laughter)

LW: Anyway, this will have implications for where we are going in a minute when we turn to your text, and we can come back to it. But first talk to me a little bit about how all of these themes are playing out right now in your real professional life, as a prelude to getting us to start talking about Ubi Sunt. In the Watchmaker’s Note you provided at one point at the end of the novella, you say that some of the “conversations” in Ubi Sunt are straight out of what's actually happening right now. How is that different than it was a year ago? And how will it be different a year from now?

(TO BE CONTINUED IN OUR NEXT ISSUE)

NOTE:

Blaise’s novella Ubi Sunt is officially out from Hat & Beard Press in Los Angeles this week and can be procured at a 20% discount from the publishers directly if you take advantage of this link, where you will also get a sneak preview of the book’s remarkable design, and where, too, the $25 dollar book will register as $20 as you check out.

* * *

A CLOSER LOOK AT ANOTHER MENZEL

Last issue, my discussion of the Giant at the Prado concluded with a remarkable little painting by a colossal little man, the nineteenth century Prussian master Adolphe Menzel’s study of his own foot, with toe rampant.

That reference in turn has had me thinking once again about an even greater painting by the same master. I should perhaps state outright here that I’d never really given Menzel that much thought, that is until about two decades back, when the eminent critic Michael Fried published his remarkably bracing monograph, Menzel’s Realism: Art and Embodiment in Nineteenth Century Berlin. Fried asserted, for starters, that Menzel was the third of the three great realist painters of that century, that what Courbet had been to France and Eakins to the United States (Fried had already written extensively on both of those), Menzel was to Prussia. Which was news to me.

But Fried was so passionately convincing on the subject that the next time I visited Berlin, I made a point of seeking the artist out—the Alte Nationalgalerie, there on the museum island in the middle of the Spree, is thoroughly stocked with masterpieces by him (and the nearby Kupferstichkabinett archive of prints and drawings allows visitors to order up braces of notebooks and sketches for individual viewing). Many of Menzel’s most famous paintings are veritably huge, notably including his throbbing paean to then-recent industrialization, Iron Rolling Mill, (138 x 254 cm), or a whole suite of exquisitely detailed historical canvases celebrating the career of his apparent hero, Frederick II (“the Great”) from the previous century, whether waging war (318 x 424) or playing the flute (145 x 205). But the image I kept returning to, was another historical vignette:

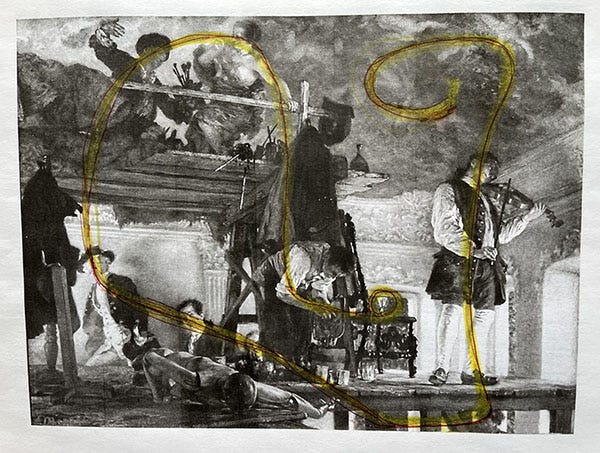

Menzel’s Crown Prince Frederick Pays a Visit to the Painter Pesne on His Scaffold at Rheinsberg, from 1861 (when Menzel would have been 36), actually a gouache on paper, and an astonishingly small one at that—only 24 cm by 32, or 9.45 inches by 12.6, which is to say roughly the dimensions of the screen of the Mac laptop at which I am currently typing, as hard as that may be to credit given the lavish density of its detail.

The Crown Prince Frederick (born 1712) and his father Frederick William I seem not to have gotten along: the authoritarian militarist patriarch did not much fancy his son’s interests in music and philosophy (and apparent homosexual tendencies) and by 1736, the father had remanded the young heir to a fastness of his own, in Rheinsberg, about 100 kilometers north of the capital, a castle which the crown prince quickly took to refurbishing. Menzel’s gouache captures a moment a few years later, in 1739, when the Crown Prince and his train were paying a visit on the French-born court painter Antoine Pesne as he was up on the scaffold laying in a rococo ceiling for the new ballroom (that’s Frederick in the lead at the top of the stairs, and his architect Georg Wenzenslaus von Knobellsdorff—great name!—right behind him, while the court violist Franz Benda, unaware, serenades the painter and his model off to the side, a sort of human boombox). As crowded as the scene is, it’s also remarkably airy, the doors clearly open to the breeze from outside (and how does Menzel achieve that effect?).

And there is a whole lot going on. Back in the day, I used to deploy this painting in my Fiction of Nonfiction classes at the point in the semester when we began to shift from the Paradox of Form to the Paradox of Freedom. The former involves the fact that, as we all know, everything that happens is in fact the result of sheer contingent roiling chaos, there are so many things that could have happened otherwise—nowadays, this is where the notion of branching metaverses comes in—but people can’t stand that fact and rely on the retrospective writer to impose some sort of form on all that chaos, albeit an individual vantage (hence the need for a first-person voice, not out of megalomania but out of modesty: this is just one person’s version of how things evolved as they did, another person would have offered another version). The wider point being that the imposed form is therefore of necessity a kind of fiction (and not objective reality, of which there is no such thing). The latter paradox, that of Freedom, while equally self-evident, seems the former paradox’s diametrical obverse, for we all also know that everything that happens happens exactly the way it had to happen, or else it would have happened some other way (see the metaverse fantasy again, just from the other side). But the thing of it is that (as we all also sense) as it was happening, everyone involved was free to act in any other way: that’s the reality of human freedom. Once any individual acted, an investigator could tote up all the reasons the person acted in that way, but up until then everyone’s freedom (even if only to assume a distinct attitude to the unfolding reality) was as much a fact as any of the others—it’s all sort of like a zipper, wide open at the front, but closed up in an inexorable line to the other side of the sliding nub—and it is the job of the narrator to actualize that sense of things as well (which in turn may be part of what Eudora Welty means when she insists that “Making reality real is art’s job”—or, with Grace Paley: “Every character, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life”). (For a video of my entire class on the subject, see here.)

Oooh boy, how did we end up here? (See what I mean!?) Oh yeah, looking at Menzel’s painting. At this point in the class, I’d distribute postcards of the image among the students (I scarfed up a whole box of the things at the museum shop the last time I was there in Berlin) and I’d start out by asking, how many people are there in the painting? Various guesses, but then I’d follow up, are you including the guy under the violist’s left leg, leading up the rear of the royal procession—or for that matter, just in front of him, there’s that little sliver of the top of someone else’s head at the bottom of the open green space, underneath the chair. And what about the lady on the ceiling and the four circling cupidons? But those are painted entities, some students would invariably object, which of course they are, but then aren’t all the others “painted entities” as well? As is the foreshortened mannequin at the front of the lower scaffold nearest to us (note the remarkable way its flank guides our eye along the royal processional as it climbs the stairs behind). And for that matter, what about the chair itself and the presence (if not the person) it suggests: Menzel’s own custom-built chair, with its foreshortened legs to accommodate the artist’s diminutive stature (recognizable from photographs of Menzel’s studio) with a dainty crystal sherry glass poised on its seat. And further, what of the presences suggested by the draped coats, the one off to the far left of the canvas, from our point of view, with that vulture-like beak (echoing the odd extension of the model’s right arm above), and the other right above the assistant leaning over cleaning the palette, which, along with the hat hanging just above it, seems to suggest the silhouette of a sort of butler, offering a tray (the butt end of the upper scaffold) upon which sits a carafe of some sort (perhaps filled with the very liqueur that has found its way into the artist’s crystal glass).

Anyway, as I say, a whole lot going on. But, turning first to the question of form, note how tightly Menzel has managed to wind the composition, almost like a tension-taut spring. Note how our eyes get guided through the scene:

Indeed the thing seems wound within an inch of its life. But look more closely and you will realize that this is the very last second that the figures will be so exquisitely arrayed, as if in the hollow of a nautilus shell (sheer golden section heaven!). Because look what’s going on: The king and his entourage are ascending the stairs, and their own attention is being drawn to some sort of ruckus transpiring up there on the top scaffold where Pesne seems in the midst of some kind of possibly me-too-like indiscretion, drawing the half-naked model into some sort of untoward embrace—or else, maybe to put a milder construction on the situation, he is trying to show her how to pose in a more entrancing dancelike manner. At any rate, she seems a bit discomfited (grabbing the makeshift balustrade with one hand, the other contorted into that weird defensive claw) and uh-oh: she’s just kicked a can of brushes which are already tumbling into free space, one of them pointing to the crown prince, the other about to come crashing onto the rear of that leaning assistant. In less than a second, all chaotic hell will be breaking loose. The surprised assistant jumping to attention, likely splattering the boom-box violist and possibly the crown prince as well, depending on where the slathered palette ends up flying… Form and freedom, indeed: compressed one upon the other in the manner of a True Master.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

Animal Mitchell website.

* * *

REPRISE II: AN ONGOING APPEAL

See what I meant last time about how my wingman David Stanford so often seems to be laying in some sort of sub rosa commentary in his choice of drawings with which he concludes these sessions?

This time out, I assume he’s nudging me to remind everyone about how we launched our funding appeal with the previous issue, and have been gratified by the response thus far (Thank you!) but still have a ways to go. Our intent is to not withhold any of our offerings behind any sort of transactional paywall; those who can't pay needn't have to. But that will only work if enough people who can afford to support this enterprise choose to do so. So please click the "Subscribe Now" button below (even if you have already been receiving the Wondercabinet for free up till now), and, if possible, sign up in one of the proffered categories. (Heads-up to anyone in an extravagantly supportive mode: you can increase the default dollar figure in the "Founding Member" option.)

Equally important, please share the existence of our publication with friends or colleagues or acquaintances who you think might also enjoy it. We were gratified that Issue #16's "Determining the True Name for Things in Ukraine" was featured in Substack Reads this week, which brought a lot of new readers on board (Welcome!).

Thank you, all of you, for your ongoing attention (which is always the most gratifying kind of support), and see you next time!

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Part two (of three) of my conversation with Blaise Agüera y Arcas, in which the contours of our spirited disagreement grow more clear; the launch, in a new iteration, of our communitywide Convergence Contest; and more…

We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Loved the interview.