WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME!

This week, as we round the corner on this five-part All That is Solid convergent taxonomical exercise, we’ll start out with a general recap to help get everyone back up to speed before launching into Part Four, which will focus on the sorts of things that happen when individual artists or groups of artists impinge on one another. Followed by a visit to a remarkable show, currently still up, of new work by the 94-year-old California Light and Space master Robert Irwin, whose career I have been chronicling for over forty years.

This Issue’s Main Event:

All That is Solid:

Toward a Taxonomy of Convergences & A Unified Field Theory of Cultural Transmission

It occurs to me that some readers may be joining this “All That is Solid” stemwinder of a series for the very first time with this issue, and might be feeling a little confuddled as to what we could possibly be up to here. (The same, for that matter, may apply to some of those who have been with us from the start.)

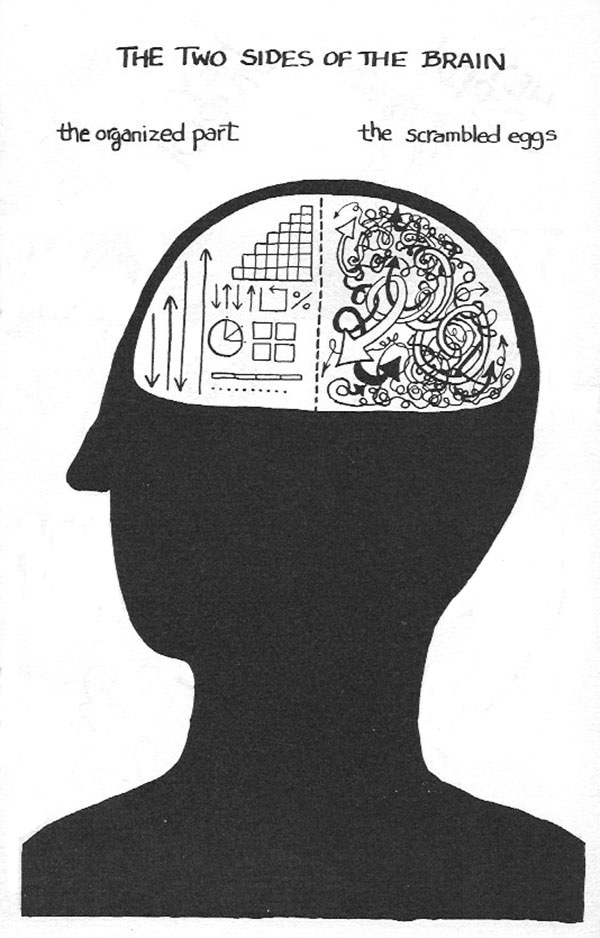

So time, perhaps, for a bit of a recap. Suffice it to say that I myself have long evinced an interest in—nay, a compulsion toward—free associative linkages, those moments when one image or passage or landscape or thoughtscape puts one (or at any rate, me) uncannily in mind of another, an association that then veers off into myriad further such freeform leaps. “Uh-oh,” as my beleaguered daughter used to say, “Daddy’s having another one of his loose-synapsed moments.” Convergences, as I would endeavor to correct her. “I know, I know,” she would subsequently take to averring, sarcasto-preemptively, in her later years, “it’s a neurological virtue.”

Virtue or not, the tendency led to a whole body of work, an ongoing flood of convergence pieces initially lodged one at a time across early issues of McSweeneys, subsequently collected by the good folk there in a summary volume, Everything That Rises (2006), which in turn led into a contest at McSweeneys online, where readers were invited to submit their own instances and I was expected to respond, resulting over the years in a truly prodigious trove of such fare and spawning a whole set of fresh questions about the entire endeavor.

Particularly, eventually, with regard to a single such submission in particular, that of one Benjamin Morris, who’d become convinced of the especially striking (and disconcerting) similarities between Paolo Uccello’s St George and the Dragon (circa 1470) and a particularly unsettling Dinner Scene from Eric Fischl’s Krefeld project (2002). Because, really, seriously, what was going on there—was it us or was it them?

At which point I myself decided to try to bring some order to this whole loosey-goosey passion, to develop, that is, a sort of taxonomy, as it were, of such rampant convergent effects, and then, eventually, to inquire as to which, if any, might be seen to be operating in that particular pairing, or for that matter any of the others. With the long-term hope that such an investigation might yield some wider truths about the whole business of cultural transmission, and indeed culture as such.

We’ll see about that. But for those just joining us, you find us in medias res. If you want to catch up, you can go back to the beginning of the series in Issue #11, and move your way on through subsequent issues across which we anatomized such categories as Apophenia, Projection, Affinities, and the manifold varieties of Co-Causation (see the handout below which I used to distribute when I gave periodic lectures on the theme). This time out, we will be considering some of the slippery mysteries attendant to the category of Direct Influence (forward, backward, conscious, unconscious, and so forth).

Welcome aboard. If nothing else, you may come to share in Leonard Woolf’s conviction, as expressed in the title of the final volume of his magisterial series of memoirs, that, indeed, The Journey Not The Arrival Matters.

PART FOUR:

DIRECT INFLUENCE

Up till now we have by and large been examining culturewide convergent effects; from here on in, or at least for the next good while, we will be exploring the kind of things that happen as one artist or thinker or group of such artists or thinkers impacts upon another—both forward and backward, and consciously and unconsciously.

BACKWARD AND FORWARD

Ordinarily, for example, we speak of Virgil’s influence upon Dante, and that sort of thing is pretty self-evident. T.S. Eliot was hardly the first, though he might have been one of the most eloquent, to speak of the converse influence, which is to say Dante’s upon Virgil, the way those after Dante cannot help but read Virgil with Dante in the back of their minds.

We read, Eliot suggests, the strong poets through the sensibilities of their successors (of course, in saying so, Eliot was making a play for that kind of hegemonic status, and to a large degree, at least among the so-called New Critics, he pretty much succeeded: Dante influenced Eliot but Eliot returned the favor).

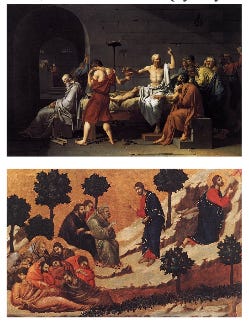

A somewhat more subtle relationship exists, as it were, between Socrates (by way of Plato) and Jesus Christ (by way of the Gospels). Those who read Plato’s accounts of the Last Days of Socrates, and especially the Apology (wherein Socrates’s own fellow citizens are seen to clamor for his execution) and the Crito (where Socrates is offered an escape but actively chooses not to take it) can’t help but notice the similarity with the Christ Passion story, how (granted, in inverse order), during his long night in the Garden at Gethsemane, Christ pleads with God to let “this cup” pass him by but then demurs, acknowledging, “Yet not as I will but as Thou wilt” (Matthew 26:39), after which, the following day, the assembly of high priests are seen to bray for his death (Matt 26:66). To what extent, we might wonder, is our reading of Socrates, or Plato’s Socrates, in these dialogs, framed by our familiarity with the so strikingly similar Christ story? For that matter, to what degree might Plato’s Socratic dialogs have survived and triumphed, to a degree far surpassing all the other sorts of writings being produced by other Greek philosophers during those same years, because of the way they tracked with the ur-story championed by the Christian monks and abbots (and Arab Muslim scribes) whose ministrations selected them specifically (over any others) to preserve over the intervening centuries? I suppose one could ask the question the other way around: to what extent did the Christ story, as opposed to all the other miracle narratives swirling about during those pivotal late Hellenistic/early Roman years (characterized, as they were, by a veritable surfeit of transcendence)—to what extent did that Christ narrative succeed and triumph among the intellectual elite during the first several decades of the current era precisely to the extent that the ground had, as it were, been prepared by centuries of familiarity with the Socrates story? An interesting clue in this regard is that cup Jesus prays might pass him by—because there is no cup in the Jesus story, though there is one in Socrates’s tale. What is Jesus doing invoking Socrates’s cup of hemlock, if not confirming this sort of influence, shloshing back and forth across history?

And so it goes, round and round.

CONSCIOUS

Which brings us, by a commodious vicus of recirculation, to Kurt Vonnegut (Mr. So it Goes himself), who throughout his life seemed to pattern himself, and consciously so, on his great master, Mark Twain, even down to his physical self-presentation (as so, for that matter, did that other counterculture master, Richard Brautigan.)

Such conscious acknowledgments and manifestations of direct influence take all sorts of forms.

Apprenticeship

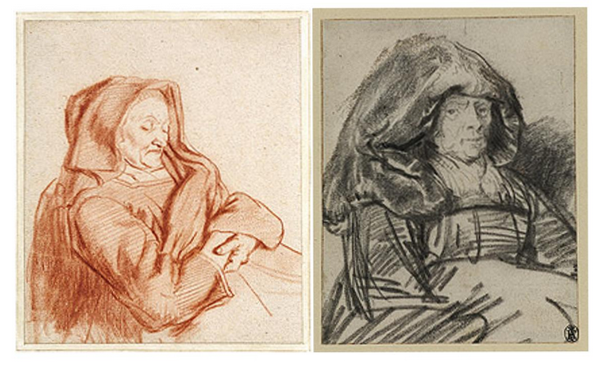

The reason that the drawings of Carel Fabritius, Samuel van Hoogstraten, Nicholaes Maes, and Gerrit Dou, and so many others, so often resemble the drawings of Rembrandt is that they were all his students and apprentices, working day after day by his side, often rendering the very same models from slightly different angles.

Indeed the likenesses can grow so close—the connoisseurship necessary to render the tight determinations so exacting—that the problem can become the occasion for entire shows, as was the case in “Rembrandt and his Pupils” show at the Getty in Los Angeles back in 2009,

which veritably brimmed with confounding instances, as for example,

And even those attributions could prove fodder for subsequent controversy, assignments of authorship either getting upended in subsequent inventories, only to be tossed all over again generations after that, with calamitous results for the market in all such things. For when it comes to monetary value, every work of art is somewhere between worthless and priceless; anything one chooses to assert categorically beyond that with regard to price inevitably tumbling into the domain of comedy.

(My friend Ben Binstock, for example, has recently been causing something of a ruckus, insisting that the Standard Bearer that the Rijksmuseum recently purchased from the heirs of Baron Rothschild for 175 million euros—a controversial purchase solely on the basis of its price, given what else could have been purchased for that amount of money—is in fact a Ferdinand Bol.)

My grandfather, the eminent Weimar-era émigré composer Ernst Toch, had a peculiar apprenticeship all his own. He liked to relate how, though he was clearly an aural prodigy of some sort, his parents (lower middle class Viennese Jewish merchants, only a generation out of the backcountry shtetl) had little use for music and more to the point couldn’t imagine his ever being able to make a living pursuing it as a vocation, so he had to procure what musical education he could in secret—which he did by hoarding his groschen and purchasing pocket scores of Mozart string quartets. Late at night, under the covers, he’d copy out the scores up to the repeat sign, and then attempt his own elaboration of Mozart’s material, returning afterwards to compare his efforts with the original. “I felt crushed,” he’d recall, years later. “Was I a flea, a mouse, a little nothing ... but still I did not give up and continued my strange method to grope along in this way and to force Mozart to correct me.” He would never receive any formal compositional training. And though supplemented as an instructor by Bach and the other masters of the high tradition, Mozart remained the reigning god in his pantheon. “If Mozart was possible,” he would sometimes declare, “then the word ‘impossible’ should be eliminated from our vocabulary.” Whenever he encountered anyone complaining about Mozart’s dying so young, he’d erupt, “For God’s sake, what more do you want from the man?”

As it happens, Ernst proved a complete aberration in our family line. There was no particular musical aptitude before him, and not much after either. Certainly not in my own case, at any rate. Which was especially galling since not only was Ernst, my mother’s father, this prodigious composer, but my father’s mother was the head of the Vienna Conservatory of Music’s piano division before the war. It all cancelled out. More to the point, I am entirely tone deaf: I can hum a tune from memory, maintain a beat, I’m alright when it comes to dancing, but if you ask me about the first four notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, I cannot tell you whether the last note in the sequence goes up or down: I just can’t hear the difference. And yet, in many ways, Ernst has proved my mentor after all, or rather his writings about composition, and in particular his Shaping Forces of Music (an endlessly fascinating survey of melody, harmony, counterpoint, and form), have proven pivotal to my own writing career. Festooned though they are with myriad examples in musical notation of which I can make neither heads nor tails (let alone sharps or flats)—they all make perfect sense to me. Which is perhaps not as surprising as all that, the writing of narrative being much more like music than, say, like painting: both enmeshed as they are in the “sequential exposition of material across time in a formful manner,” as Ernst would say, both of them agog in “the architectonic,” as he would also say (the unfurling of fields of capaciousness and constriction across time rather than across space). I get all of that. And indeed when I’m writing—or else when I am teaching others to write—virtually all of my metaphors are to music: this passage needs to be better syncopated, you might try transposing this other section into a minor key, this passage plays flat, perhaps more pianissimo here, more andante there. And strictly speaking, I don’t even know what most of those words mean. But somehow their significance spans the chasm, which is what I mean when I say that in some strange genetic way, I was Ernst’s apprentice after all.

TEMPLATE

My grandfather fled Germany early, almost right away upon Hitler’s ascension to power (which is surprising because he wasn’t all that politically engaged—he just knew it was time to go), alighting first in Paris, then in London (where he worked on the music for a Berthold Viertel film, based on a Christopher Isherwood screenplay, the production which, years later, would form the backdrop to Isherwood’s novel of German refugees adrift at the outset of the Hitler era, Prater Violet). From there Ernst moved on to New York, where he was on the founding faculty of Alvin Johnson’s University in Exile at the New School. That Christmas, Johnson gave his seven-year-old daughter Franzi (my future mother) a book of a then pretty much unknown Italian folk tale, “Pinnochio.” Reading the book to her, Ernst was so smitten with the story that he went on to compose his own Pinnochio, an antic romp of an overture which was then performed by Otto Klemperer’s LA Philharmonic a year later, after the Tochs had moved on to Southern California. The story goes that Walt Disney either heard the piece or heard of the piece on this occasion, which is how he first got wind of the Pinnochio story. And a few years after that, in 1940, Disney’s Pinnochio (stripped, alas, of Toch’s participation) made its premiere. Or so the story goes in my family. (And of course the Frank Gehry-designed home of the LA Philharmonic is now called Walt Disney Hall.)

I mention all of that because our own survey of subcategories of conscious direct influence has now moved over to another drawer, that of templates, and there is no better place to study that particular phenomenon than in Walt Disney’s own shop. For time and again Disney’s animators would cannibalize the pacing, blocking, choreography, and other wizardly mischief from earlier Disney classics (especially Snow White and Pinocchio), often frame by frame for minutes at a stretch, as they set out to fashion their subsequent films. See for example the way the team behind Disney’s 1967 Jungle Book simply redeployed a template from the company’s 1961 Winnie the Pooh.

(Not that Disney was the first to come up with the system, not by a long shot: consider the sequence of Fra Angelico’s crucifixion frescos in the lesser monks’s cells at the San Marco monastery in Florence. Consider for that matter Lascaux.)

So all of that makes perfect sense. But what are we to make when animation templates blow back into the real world, when real princes and princesses use cartoon imagery to frame all of their wedding fashion decisions?

Permission

A final subcategory of conscious direct influence, less literal minded perhaps than that of templates, might be dubbed permission—the sort of thing that happens when one great master’s breakthroughs give permission to successive craftsmen to forge into similar terrain. Take, for example, the events of 1965 (roughly halfway, I just happen to notice, between the releases of Disney’s Pooh and their Jungle Book) when in March the previously exclusively acoustic young folksinger Bob Dylan released his latest album, Bringing it All Back Home.

If only. For Dylan was doing anything but staying home. One side of the album retained its acoustic allegiance, but on the other, Dylan veritably shocked his fanbase by allowing himself to be backed by an electric band. A few months later, on July 20, Dylan released an electric single and a few days after that, on July 25, at the Newport Folk Festival, audiences greeted his resort to electric guitar with hoots of anger and derision.

And yet with time, audiences grew used to Dylan’s new sound—and more than that, he gave fellow musicians permission to follow suit in two distinct ways: folksingers could follow him into an electrical backdrop, but perhaps more importantly, electrical musicians could start lacing their lyrics as well with the sorts of radical political content that had all along characterized so many of Dylan’s offerings.

*

UNCONSCIOUS

Direct influence isn’t always conscious, however. Sometimes it makes itself felt through more sinuous devices. As for example in the case of

Overriding cultural frames

On October 9, 1967, Bolivian army commanders working in consort with the CIA finally hunted down and killed Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara, and several hours later ranged themselves alongside the corpse for an official trophy photograph. Some months later I remember reading a piece by the English Marxist critic John Berger in which he suggested that we all knew the image the Bolivian commanders must have had in the back of their minds as they ranged themselves for this photo, the image as if hotwired in the backs of their minds that taught them how to pose and taught the photographer (Freddy Alberto) where to stand to frame his shot, that iconic image of death as demonstration. They must all have been thinking, Berger insisted, even if just below the threshold of consciousness, of Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson. Note the cadaver on its plinth at a diagonal to the picture plane, its feet angled bare-soles-forward; the way the top commander dangles his hand over the corpse’s exposed belly, the way the others lean in to glean a better vantage.

I remember thinking at the time (I wasn’t even out of high school yet): Gee, this guy Berger doesn’t read the newspaper the way I read the newspaper—but that his way provided a powerful vantage on the way images constantly rebounding about the overriding cultural surround provide a context for the creation and reception of subsequent images. It was a bracing early lesson—regarding more on which, later.

Guilty Conscience

Sometimes images trail dark associations, almost unbeknownst to themselves, or anyway to their progenitors. Consider, for example, this unsettling pairing: on the left, a Nazi propaganda poster exhorting the good Aryan mothers of the Fatherland to bear larger and larger families; on the right, a poster from Vladimir Putin’s political party exhorting Russian mothers to precisely the same purpose (post-Soviet Russia, after all, being in the process of posting some of the worst population decline figures in the world). The point of course is that the backdrop imagery isn’t just similar, it’s identical, and one can’t help but wondering what’s going on. Was the Russian graphic artist being intentionally subversive quoting the Nazi model (shades of “Help, I’m being held captive in a Chinese fortune cookie factory!”)? Or was this rather simply a case of latter-day webitis: graphic artists trawling the net for images illustrative of a given assigned theme, in this instance maybe “wholesome family life,” displaying no interest whatsoever in the prior context of any images they might happen to latch onto? Either way, the results can be revealing.

The Anxiety of Influence

A final subcategory in this inventory of unconscious direct-influence effects derives from a seminal notion advanced by the prodigious American literary theorist Harold Bloom in his 1973 book of the same name, The Anxiety of Influence. Although Bloom’s hugely (albeit ironically) influential text focused on the way poets in particular are constantly (if unconsciously) misinterpreting or even occluding altogether the achievement of earlier poets, precisely so as to be able to clear a space in which they might themselves begin to create, the same Freudian-Kabbalistic framework can fruitfully be applied as well to the history of visual artists and other sorts of thinkers and their relations with their forebears as well.

Take, for example, the case of David Hockney, one of the most sophisticated artists around when it comes to an awareness of the artistic traditions out of which he emerges. He is constantly talking about other artists: Van Eyck, Caravaggio, Turner, Constable, Ingres, Picasso, Kitaj—everyone, that is, except the one artist whose life work and creative project most obviously resembles his own: Henri Matisse, that other great twentieth century colorist of the sensual and celebrant of the pleasures of bourgeois comfort.

One will hardly ever hear the man’s name cross Hockney’s lips: perhaps just too close for comfort.

At a, granted, much less exalted level, it might behoove me at this juncture to point out how though I myself refer to Freud all the time, I never so much as mention Carl Jung. For some reason, I don’t know why, the man’s crackpot theories of synchronicity, primordial archetypes, the collective consciousness and the like hold no interest whatsoever for me. I’ve never so much as opened a book.

*

Now, as we round the bend toward the final sets of cabinets, we begin to reverse the polarities of our likenesses. No longer will we focus on the ways in which one artist or thinker might, consciously or not (forward or back), have influenced the work of a successor. Now instead we focus on the way successor generations actively pay tribute to (or, in more extreme cases, flagrantly cop from) their predecessors. Starting, for example, with

ALLUSION

the conscious planting, that is, of indirect references to earlier source material in order to bring out deeper layers of significance, a practice which itself can take a variety of forms, beginning perhaps with

Invocation

the sort of thing one notices, going back to an earlier example—in Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson—in which the young painter (only twenty-six years old at the time!) with his stunning image of this bearded common thief’s cadaver, splayed out like that on a table, arms at his side, with a loincloth barely covering the midriff of his otherwise bare body, must clearly have been invoking earlier images, such as Mantegna’s, of the Lamentation over the only-just-crucified Christ.

The resultant shiver of an association to Christ, who was likewise Himself crucified among common thieves, immeasurably deepens the significance and suggestive force of Rembrandt’s image: Ecce Homo, indeed. And though the thief’s corpse may not be subject to imminent resurrection, Rembrandt’s handling of the image suggests, it may yet attain a different sort of afterlife by way of the fresh knowledge it can extend to those witnessing the professor’s dissection. (Look, the professor seems to be saying, with these arm muscles here, you can move a living hand this way.) (Look, the 26-year-old Rembrandt seems to say, thanks to paintings like this I will be immortal.) Death, at any rate, be not proud.

Incidentally, going back to our own earlier invocation of this image, it’s worth noting that Che’s iconic afterlife has everything to do with the way the image of his death, filtered by way of that Anatomy Lesson association on back through to images of Christ on his deathbed, summoned forth its own suggestions of a Resurrection and the Life. The image of Che’s martyrdom retrospectively grounds all those Christlike images of him in life, an afterlife as it were, that would go on to blossom forth across all those college t-shirts and posters. To be clear, I’m not referencing politics here one way or the other (nor I submit are most of those who don the t-shirts or post the images); I’m only talking, once again, about the way that prior images create a context for the reception of subsequent ones (and that artists know this). Had the dead Che not been bearded on the day of his death, had he instead looked like the clueless fedora-wearing fellow below, none of it would have worked. Who is that incidentally? People I’ve randomly asked have suggested everyone from Desi Arnaz to a portly Frank Sinatra, but in fact (as those of you who remember the Guess Who Convergence back in Issues #3 and #4 of this Wondercabinet will recall), it’s Che himself, disguised for his fake passport as an Argentinian businessman, on his way to Africa, a few years before his Bolivian death.

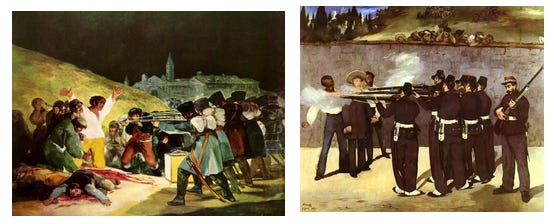

Speaking of Latin American history, consider an earlier instance: the way Manet consciously invoked Goya when depicting the execution of the Emperor Maximilian in Mexico City at the climax of the 1867 Revolution there, just months earlier.

And now consider the whipsawing historic cross-currents to which Manet’s invocation so conspicuously alludes. For the Spaniard Goya was earnestly memorializing the defeated Spanish defenders of the city of Madrid as they were being mowed down by triumphant French forces under Napoleon, the day after the latter’s victory on the 3rd of May, 1808 (the earnestness of Goya’s intent being reinforced by that Crucifixion echo in the central figure’s outstretched arms). Manet’s invocation of the Goya image for his depiction of the way the victorious Mexican revolutionaries now turned the tables of history by executing Maximilian, the French Emperor Napoleon III’s personal representative on the scene, reads far more ironically: the first time as history, the second time as farce (as Marx himself dubbed the earlier episode of the soon-to-be Napoleon III’s original seizure of power in Paris back in 1851). And indeed the ironical tone is reinforced by Manet’s own somewhat more farcical Christological flourish: Maximilian flanked by his two lieutenants, haloed by a sombrero.

NEXT ISSUE: The final installment.

* * *

ARTWALK: Robert Irwin at Pace

Just over two years ago—a mere month before the onslaught of the current pandemic, as a matter of fact—the California Light and Space master Robert Irwin, at age 92 in the midst of a longterm physical decline, staged what everyone was pretty much assuming was going to be his last show of new work, at the Pace Gallery’s main Chelsea space in New York.

That’s certainly how I framed matters anyhow in the piece that I contributed to the New York Times (Feb. 13, 2020) in my capacity as his longtime chronicler (going back over forty years to when he’d been the subject of my very first book, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees). For me, writing that piece evolved into a sort of summary celebration—a fond send-off on the occasion of a singularly accomplished and extraordinarily lovely exhibition. Bob, I suggested, had nailed his landing, concluding, “So here we arrive, near the culmination of a magnificent career: Rococo minimalism meets Lindy Zen.”

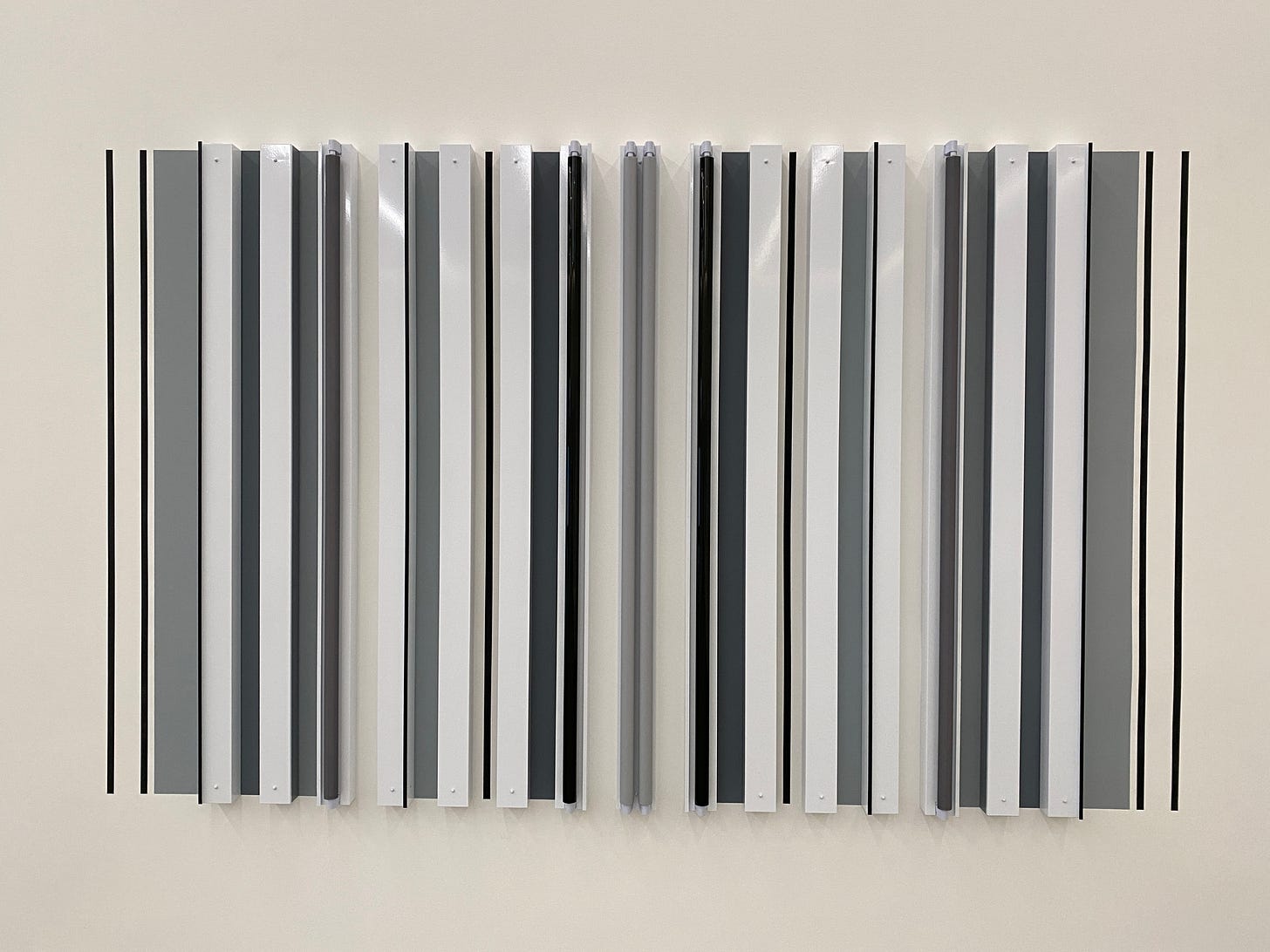

Good thing I included that fudge “near.” Because, this month, at age 94, Irwin has perpetrated yet another show of new work (same place), largely the product of his own pandemic isolation back in his San Diego homebase, and this one is if anything even more commandingly impressive than the one before. Not only does Irwin fill one floor with an entirely new set of wall array pieces, his so-called “Unlights” (on account of their continuing distribution of lusciously wrapped though electrically disconnected fluorescent lightshafts), unfurling even more compoundingly confounding effects than last time. But on a separate floor, he has replicated some of those same effects across an entirely new series of gleaming facetted freestanding sculptures, “acrylic configurations,” as he has taken to calling those.

And the thing is, he has achieved all of this in the face of ever more daunting life challenges. His mind has gradually been dematerializing—he has hardly any short-term memory left (within a few minutes of starting a conversation he seems unaware that he is reverting to the same subjects and phrasings with which he began, and often he seems incapable of quite making it to the end of any sort of extended consideration)—and yet his aesthetic judgment and capacity for crisp distinctions and exacting determinations in that regard seems entirely undimmed.

Much of my writing about Irwin, including that original 1982 Seeing is Forgetting volume (and its subsequent second expanded edition in 2007) and the series of occasional pieces I’ve been continuing to publish since (including one on the opening of his major permanent installation, fifteen years in the making, at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, back in 2016) has focused on the way that over the decades Irwin has been honing and honing his own almost preternatural capacity for focusing his attention on the immediate matter at hand, successively bracketing out every other extraneous consideration. And notwithstanding his other problems, that capacity for presence in the present when it comes to art-making still seems entirely there. (My other longtime friend, the late neurologist Oliver Sacks, subject of one of my more recent books, would have been fascinated, though perhaps not entirely surprised. I wish he were still around to discuss this all with.)

“You have to remember,” Bob’s assistant Joey Huppert reminds me at the opening, “this is a guy who until a few years ago could make out discrepancies of an eighth of an inch at a couple hundred feet: over the decades he’d trained his perceptual capacities to that level of precision—and though things have fallen off a bit from that (he’s had serious successive problems with his eyes, his back, his sense of balance, and so forth), when it comes to the studio, no matter how disoriented he may be in other ways, he still retains that same capacity for laser-focused intention.”

For the longest time, Irwin allowed no assistants whatsoever in his studio (with the occasional exception of his veteran fabricator pal Jack Brogan). But in 2007, during a major retrospective of Irwin’s work at San Diego’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCASD) in La Jolla, two of the young guards there (Huppert and his friend Michael Armstrong) spent hours and hours conversing with Irwin and at length prevailed upon him to let them help him in his studio, and over recent years the two have become ever more central to his ongoing practice. “But you have to understand,” Mikey tells me, “we may help rejigger fresh configurations of those light shaft arrays or the acrylic columns at his direction, but when Bob turns to Joey and asks him what he thinks, Joey always responds, ‘It doesn’t matter what I think, Bob, it’s what you think,’ and then Bob might suggest a slight alteration, and the process continues like that till he is completely satisfied.” And, as Joey elaborates, “The next day we set up the configuration again, to make sure Bob still approves it, and then we do likewise several days in a row, offering him the same array amidst a variety of others. And if the piece keeps passing muster several times in a row like that, then okay, we consider it finished. But not until.” (Someday someone is really going to have to chronicle what has been going on in that studio over the past several years in depth: maybe it should be me.)

At any rate, those of you, my dear readers, who can do so should definitely try to catch the show at Pace before it closes on April 30 (at 540 W 25th Street in New York). For those who won’t be able to go, I’m providing the portfolio of images below. But remember: for the longest time, Bob forbade the photographing of his work altogether because he insisted that photography could only capture what the work was not about, which is to say image, and never what it was, which is to say presence. Eventually he relented on that prohibition, but the same applies to this body of work, if not to an even greater degree. In particular, any single head-on vantage of the wall pieces flattens the experience of the work so radically as to be almost beside the point. These pieces only come alive as one moves around them—hence the somewhat more appropriate recourse to video, which helps to approximate the vertiginous savor of moving about the pieces in person, for it can get deliciously confounding trying to make out just what we are looking at (bulbs in their profusion of colors? the reflections of those bulbs off the faces of the glossy white cannisters behind them? the sleeves of those cannisters jutting out from the wall, gleaming white or could it be that they’ve been painted over, black or gray? the passages of wall, between the cannisters and in turn also reflected off the cannister sleeves, themselves painted alternatively white or gray or grayer still or black? thin intervening black zips along the rims of the cannisters, or even thin vertical lines of subtly hued tape stretched along the very surfaces of the bulbs themselves?). And indeed that we are seeing, how we are seeing, the active process involved and that is always involved in doing so whenever we are looking at anything (whether we choose to notice it or not), the wonder of that ever-ongoing process of discernment, as usual with Bob becomes the overwhelming theme of the entire experience.

And perhaps never more so than now.

*

The Unlights, downstairs:

*

The Acrylic Configurations, upstairs: various vantages

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

***

NEXT ISSUE

The conclusion of our All That is Solid survey, starting with further Allusive effects (Homage, Pun, Pastiche and Parody) and then heading past Quotation, Appropriation, and Cryptomnesia (!), on into such Plagiaristic gambits as Forgery and Counterfeiture. After which, following a sidebar consideration of the bizarre case of Helen Keller, Plagiarist, we will try to determine, once and for all, just what was going with that Uccello-Fischl overlap from the beginning of this entire exercise, in the process hazarding a sort of unified field theory of cultural transmission—nay, of culture itself! And an Important Announcement…

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Arriving a bit late at this newsletter (and only coming here because of the 1982 introduction to the works of Robert Irwin, and then an overly well-spaced series of subsequent encounters over the intervening 40 years; it can't be that long!), I'm saddened to hear of Mr. Irwin's increasing decline. The staff at Chinati/Marfa gave us some anecdotes indicating that the decline was in progress. It's been so hard, at a distant remove, to get abreast of most Irwin events. I wish we'd made it to this one in April. Now we plan to head out to Dia Beacon. The world does not place as many geniuses into our paths as we might like. Thanks to Lawrence Weschler, who in 1982 presented an example of The Real Thing, who has turned out to be realer even than I could have imagined. I know I wrote "thanks" at the beginning of the preceding sentence, and then put it within this sentence, too, but: Thanks.

Concerning the Putin propaganda image about having more children is the same one used by the third Reich - The recent book by Tim Snyder "The road to unfreedom : Russia, Europe, America" elaborates convincingly V Putin's connections to the ideology of Ilyin and other fascists. The similarity of imagery is most likely intentional.