November 25, 2021 : Issue # 4

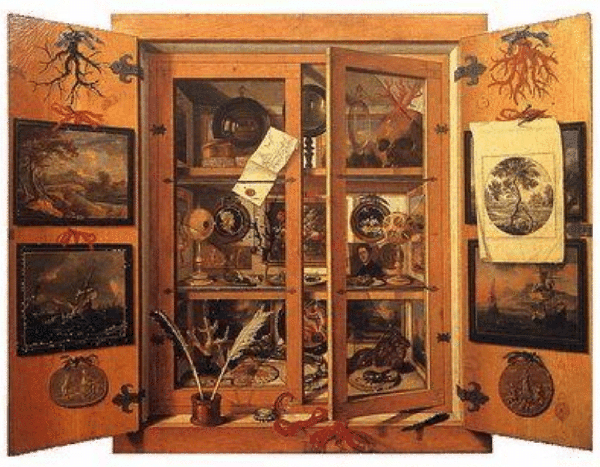

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

INTRO

Welcome back again, or for the first time to those of you just joining us. To catch up on anything you’ve missed in the whole progression up through now, check out the “Wondercabinet” page at Substack here (and to get a sense of what exactly we are trying to do with the series, consult the introduction to Issue #1). In this issue, our main event will be an extralong instance of footnotes from a book you don’t have to read, this one on ghosting and erasure, from DeKooning and Rauschenberg through the Death of Stalin; the surprising answers to last issue’s Guess-Who Convergence; a Zoom conversation with artist/celebrator of otherwise invisible domestic workers, Jay Lynn (formerly Ramiro) Gomez; speaking of ghosting, Ghostcubes!; and my toddler goddaughter goes and says the darndest thing….

* * *

This Issue’s Main Event:

STILL ANOTHER FOOTNOTE FROM A BOOK YOU DON’T HAVE TO HAVE READ OR EVER READ {Fourth in a Series}:

THIS ONE ON GHOSTING AND ERASURE

In the months ahead, as we keep mentioning, I will be publishing a new book, regarding which, further details anon. In the meantime, there’s this:

FOOTNOTE #25

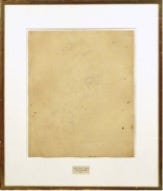

The phenomenon Berkman was encountering here, the seemingly blank page with its fugitive impress that fell out of the antique scrapbook he’d only just acquired, goes by the name, in printer’s jargon, of “ghosting,” which is to say a faint image appearing where it was never intended to appear, on a blank sheet of divider paper inserted opposite a particularly dense printed illustration. But the ghost of that illustration’s appearance, as Berkman showed the sheet to me, put me in mind of another such instance in the history of art, another such only seemingly blank page, if you will (and if so willing, you were hence to bear with me).

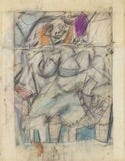

I am referring to the young Robert Rauschenberg’s legendary encounter with the great Willem de Kooning. At that moment, in 1953, de Kooning (b. 1904), was, alongside Jackson Pollock (b. 1912), arguably the reigning master of the New York art scene, proponent of that spectacularly vigorous, existentially torqued, action painting style known as Abstract Expressionism. Not only a great, great painter, he was also one of the most accomplished and subtle draftsmen of all time. Protean creator of this sort of thing, from MOMA’s collection (1952):

Anyway, Rauschenberg (b. 1925) was fairly new in town, a generation younger than de Kooning, fresh out of Black Mountain College (where his teachers and fellow students had included the likes of Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Josef Albers, Buckminster Fuller, Jasper Johns, etc.). Unlike other younger artists in New York at the time (Resnick, Bluhm, Goldberg, Mitchell, and so forth), Rauschenberg, though an enormous admirer of de Kooning’s achievement, was himself declining to pursue the so-called Second Generation Abstract Expressionist path. Instead, for example, just around that time, he’d been executing a series of White Paintings, exclusively monochromatic works that eschewed emotionally expressionist gesture altogether, intent instead on exploring and celebrating the perceptual fundament under-girding all expression, the positive active presence of that otherwise fugitive color, the way light itself for example played across such an emptied canvas. White paint on white canvas was one thing, but somewhere in there, Rauschenberg got it into his head that he wanted to follow such experiments into the terrain of drawing, another great passion of his, even though it was not altogether clear, initially, how one might go about doing such a thing. Presently he hit upon the idea of erasing drawings and began doing so, for starters, with drawings of his own, becoming increasingly entranced with the resultant trace, the look, as it were, of the wide, gummy field of smudge.

The story has been told many times (see for example the accounts in Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s Pulitzer Prize-winning de Kooning biography, or else in the Modern Masters PBS Rauschenberg documentary, which is available on YouTube). Something about erasing his own drawings was failing to fully satisfy the young Rauschenberg (they looked too much, he felt, like erased Rauschenbergs, and as such, perhaps, not accomplished enough, or at any rate too self- referential, which was never the point), and presently he convinced himself that what he needed to be doing instead was to erase the work of a full-fledged master; whereupon, screwing up his courage with a bottle of Jack Daniels, he ventured over to de Koonings’s studio and asked the revered master for a drawing of his, stammeringly explaining how he intended to erase it. Willem de Kooning, for his part, took the request entirely seriously, and following all sorts of excruciating mind games of his own, gave the young whippersnapper a page of densely worked imagery, scrawled over with all manner or crayon, pencil, and ink.

What I’ve always savored at this point in the story is the evident comedy of misunderstanding: de Kooning clearly interpreted the request in active expressionist terms, as a laying down of the gauntlet in an epic generational battle. Just as he, de Kooning, had had to slay Picasso in order to clear space for himself, here coming up was this new generation, intent on engaging in its own Oedipal rebellion. Talk about clearing a space! Talk about existential passion! So he met the challenge head on, giving the boy a particularly densely worked page that would prove especially difficult, if not impossible, to erase. Whereas for Rauschenberg, the thing was (or so he was always to claim), Oedipal aspirations had nothing to do with it; nor even did the process of erasure, which in this instance was indeed to last several months; he insisted that he simply loved how the gummy erasure smears looked.

The way they reflected the room, for example, the Zen-like attention they invited and sustained. For him, they weren’t gestures of nihilist defiance; rather, they constituted a sort of “poetry.” (John Cage, for his part, credited Rauschenberg’s white on white experiments with giving him the courage, immediately thereafter, to begin pursuing his own extended evocations of silence, as in that legendary piano piece 4’33”, which is to say four minutes and thirty-three seconds of a pianist simply sitting at the keyboard, never so much as brushing a key.)

Anyway, all of this now came back to me, looking at that empty page of Berkman’s with its after-image shimmering or not just beyond its surface. (I told you we’d get there if you just bore with me!) But I couldn’t help free associating to the work of an artist in the immediately following generation, how, observing the de Kooning-Rauschenberg battle − the Old Man seized by the anguished Oedipal implications of the erasing gesture, and the Younger Man by the splendor of its look – Claes Oldenburg (b. 1929) in effect, the grandson in this configuration, would subsequently take to proclaiming: Forget the erasure, look at the Eraser! Look how beautiful it is!

And anyway, if you will permit me one last associational cartwheel, all of that somehow reminded me of a passage from my old New Yorker colleague Ian Frazier’s magnificent book of Travels in Siberia, where he related how:

Having read a lot about the end of Tsar Nicholas II and his family and servants, I wanted to see the place in Yekaterinburg where the event occurred. The gloomy quality of this quest depressed [Frazier’s guide] Sergei’s spirits, but he drove all over Yekaterinburg searching for the site nonetheless. Whenever he stopped and asked a pedestrian how to get to the house where Nicholas II was murdered, the reaction was a wince. Several people simply walked away. But eventually, after a lot of asking, Sergei found the location. It was on a low ridge at the end of town, above the railroad tracks and the Iset River. The house, known as the Ipatiev House, was no longer standing, and the basement where the actual killings happened had been filled in. I found the blankness of the place sinister and dizzying. It reminded me of an erasure done so determinedly that it had worn a hole through the page.

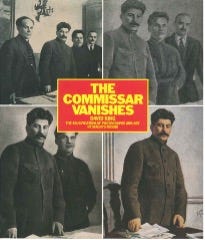

Which in turn set me to thinking a bit further about that legendary de Kooning / Rauschenberg encounter, for look again at the year: 1953. Height of the Cold War, and indeed the very year Stalin himself died. Stalin, that gruesome master of the political erasure, as subsequently documented by David King in his 1997 classic, The Commissar Vanishes: A tyrant who became convinced that it wasn’t just necessary to eliminate one’s opponents: his own legitimacy resting, he became ever more obsessively certain, on his erasing all evidence that they had ever even existed at all. Culminating with Himself All Alone, triumphant, unchallenged and unchallengeable, supremely sovereign against a serene white on white backdrop. Talk about ghosting.

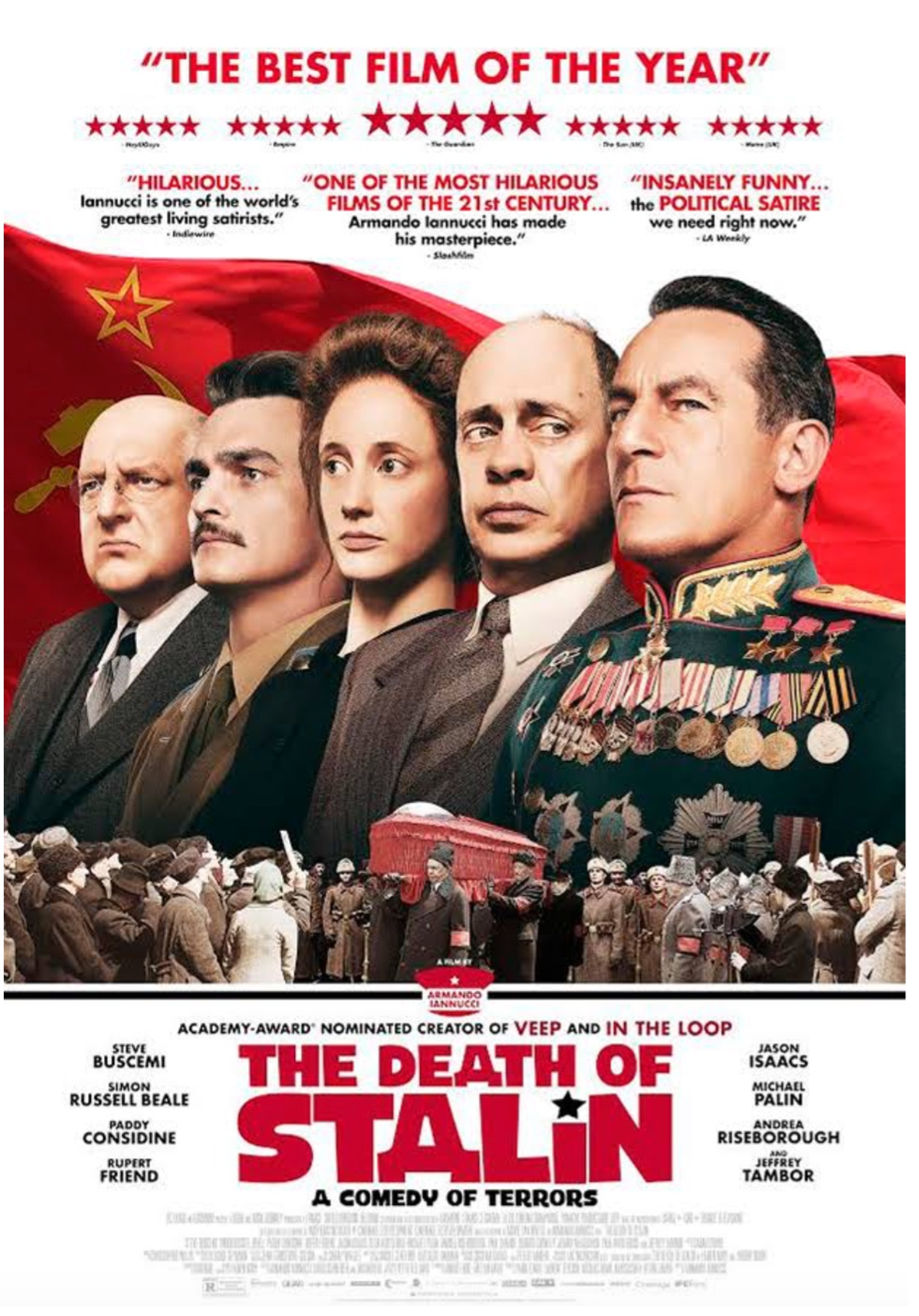

But I know, I know: I digress. Still, if you will permit me just one further footnote, as it were, to that last association: Because just a few years ago, in 2017, as the studio was seeding the ground for the forthcoming release of Armando Iannucci’s marvelous historical satire The Death of Stalin with a blitz advertising campaign featuring an array of profiles of the film’s puffed-up star figures,

one of those stars, Jeffrey Tambor (playing the weasly Georgy Malenkov), suddenly found himself the subject of accusations of sexual impropriety (charges he fiercely denied) on the set of his earlier thrice Emmy-nominated gig as the transitioning (male to female) father on the series Transparent. No sooner was he literally canceled from the eponymous role on that series than he also poof! found his image (and character) summarily vanishing from the ads for the upcoming Stalin movie. Replaced by a woman, no less!

First time tragedy, as Marx himself might have observed: second time farce.

* * *

ANSWER TO LAST ISSUE’S GUESS-WHO CONVERGENCE

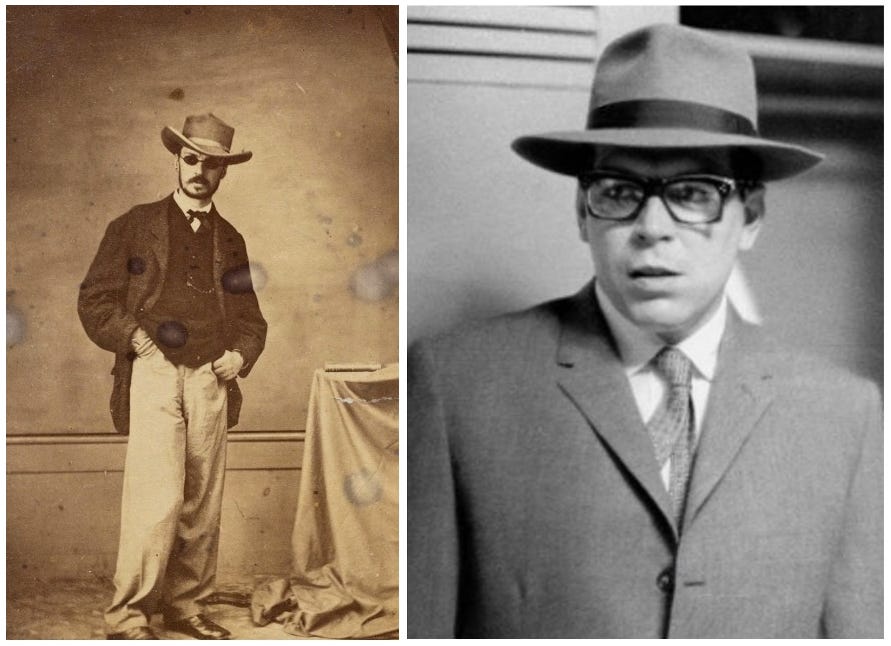

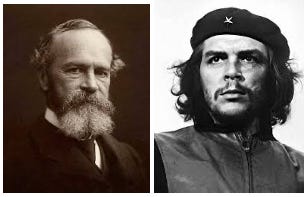

Okay, this is your last chance to hazard a surmise. Who are they? (These are both people you know, or at any rate have heard of.)

Recall the two clues: The photos were taken exactly one hundred years apart, in two separate locations in Latin America.

And here are a few final clues: The reason you may be having trouble recognizing them, in both cases, is that you are used to seeing them much more expansively bearded. Also, neither of them is usually portrayed wearing glasses. Nor do you associate either of them with those strikingly similar sombreros.

*

The Answers:

William James in Brazil in 1865, where he had volunteered to serve as an assistant to one of his Harvard mentors, Louis Agassiz, on a collecting expedition on behalf of the school’s recently founded Museum of Contemporary Zoology. On the trip, he contracted a mild case of smallpox which temporarily blinded him, hence the deceptively-hipster sunglasses.

&

Che Guevara in Argentina in 1965, bored with his bureaucratic post-revolutionary life in Cuba, and so, disguised as a (similarly bespectacled) Uruguayan businessman for the photograph in his fake passport, en route to Africa, where he hoped to be able to help foment further actual revolution. Failing that, he presently went on to Bolivia.

The Contest Results

John Hastings submitted two double-guesses and was half-right on one.

Guess #1: No, it is not The Sundance Kid and Leon Trotsky.

Guess #2: No, it is still not The Sundance Kid, but it is Che Guevera!

As this week’s sole (half-)winner we will be happy to send John a copy of Ren’s 2003 creation, Omnivore: A Journal of Writing and Visual Culture. Please write to us at: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com and let us know where you would like it sent.

* * *

A-V ROOM (Speaking of Latin America)

In conversation with JAY LYNN GOMEZ (formerly Ramiro Gomez)

Ramiro Gomez was born in 1986 in San Bernardino, California, to undocumented Mexican immigrant parents—his father a trucker, his mother a janitor at his own elementary school—and displayed the sort of artistic talents early on which presently won him admission to CalArts. But he left that institute within a year and instead secured employment as a nanny for an entertainment industry family in the Hollywood Hills. Still, his artistic proclivities were hardly dimmed. He began by taking back-issues of architecture, fashion, and design magazines out of the family’s recycling bin, squirreling them back to his room, and subtly doctoring the glossy high-life ads and features by painting in images of the low-income nannies, housecleaners, gardeners, and others who made such life possible. He went on to raid the trash bins at electronics stores for their discarded cardboard boxes, which he in turn fashioned into life-sized painted cut-out flats portraying the sorts of workers whose work goes largely unnoticed, and then subversively leaning such cut-outs against hedges and sites all around town. After which, quitting his nanny job and securing a small studio, he began producing sly pastiches of iconic David Hockney paintings, uncannily reversing their class polarities.

Around this time, in 2016, I profiled the young artist for a full-color Abrams monograph, Domestic Scenes, since which Gomez’s work has gone from strength to strength, getting acquired by major collectors and museums alike, albeit invoking and provoking all sorts of confoundingly paradoxical issues along the way. The sorts of long occluded issues, indeed, that veritably cry out for exploration in the context of Venice’s recently-concluded high-end Architecture Biennale, under the auspices of which this Zoom conversation took place.

Over the last few years, Gomez has been traversing a gender transition, and we concluded our dialog by exploring some of the issues involved there as well, how they in turn may have been foreshadowed in some of the artist’s earlier work, and what they may portend for the future.

Watch our conversation here.

* * *

FROM THE INDEX SPLENDORUM

For the past several decades I have been compiling an ongoing list, which has ballooned to over a hundred pages, of URL links to especially cool videos, miscellaneous and diverse, which I have happened to stumble upon while dallying about the web. From time to time, I’ll be sampling that log of splendors, as in this instance from 2013, in which the Swedish artist and designer Erik Åberg first ran his ghostcube creations through their splendid paces:

Check Åberg out online: there’s a whole lot more where those came from. And note that in the meantime, Åberg mounted a successful Kickstarter campaign to develop kits whereby customers can fashion their own ghostcube constellations.

For more on that, go here.

* * *

LEAVES FROM MY COMMONPLACE BOOK

Meanwhile, for the past forty years I’ve likewise been compiling an ongoing series of pocket commonplace books into which I’ve regularly been inserting particularly salient passages read or comments overheard (see the Corona Garland from Issue #1), and I’ll occasionally be dipping back into those as well in the months ahead, as in this recent case:

My two-year-old goddaughter Artemis to her father Trevor:

A: “I had an idea.”

T: “Oh yeah, what was it?”

A: “It was GREAT!”

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

NEXT ISSUE

Ren’s service as an eclipse wedding rabbi (to Artemis’s parents no less) gets him yammering about things cosmic and the very origins of humanity; the return of Walter Murch for another Zoom, this time excavating the astonishing mathematical secrets buried deep within the Egyptian pyramids; yet another footnote; and more…