November 11, 2021 : ISSUE #3

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

ONWARD!

Three issues in and we may be beginning to get the hang of this thing. It’s good to have subscribers back and especially good to have a fresh brace of new visitors, who are invited to catch up with our first issue (which includes a general statement of our intent regarding this whole enterprise), and our second issue (which includes the first part of the profile of Jack Brogan that concludes in this current third issue). In addition, this time out we are featuring. in the A-V ROOM, Ren’s conversation with photographer Ken Gonzales-Day on the historical reality and artistic representation of Lynchings; another FOOTNOTE, this one regarding a plethora of klutzes; and a special GUESS-WHO CONVERGENCE. If you enjoy what you’re encountering, please do subscribe in the box at the bottom of the scroll: just enter your email address and you’ll receive another “Wondercabinet” in your emailbox every other Thursday, all for free (at least for the time being). And please, please, pass on word of our little project to your friends and colleagues (just forward them the link!)—and let’s see if we can’t keep growing this thing.

* * *

This Issue’s Main Event:

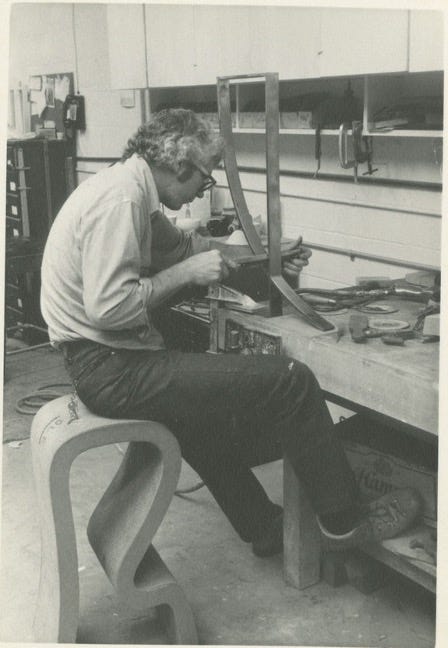

The Alchemist: A Profile of Jack Brogan

PART TWO OF TWO

Continuing on with the story of Jack Brogan, arguably the premier fabricator and conservator to the artists of Southern California’s Light and Space movement across the past half century, still vividly active well past his own ninetieth year. In Part One, last time out, we followed Brogan from his childhood in depression era rural Tennessee, literally traipsing about barefoot in the steps of his larger-than-life jack-of-all-trades grandfather, amassing a veritable cache of practical expertise in the process, through his various early deployments among others at the Oak Ridge nuclear facility and as an army sharpshooter in the Korean War, on through his migration to Los Angeles in the late fifties, where he quickly established himself as an expert craftsman across all manner of media at the behest of Hollywood directors, real estate developers, furniture designers, and the like, up through the day when Robert Irwin (one of the earliest proponents of the Light and Space aesthetic) walked into his workshop studio, avid for material advice.

…And word began to get around: Irwin saw to it. These were the very years when those who would become the Light and Space artists were pouring themselves into the pursuit of translucence, of amorphous atmospheric effects, the quicksilver capture of luminosity itself. They were likewise starting to experiment with resins, urethanes, and plastics, all of which were proving devilishly difficult (not to mention dangerous) to work with. “Go ask Jack,” Irwin would urge them, and they’d soon be urging one another.

Peter Alexander sought counsel on how to cast and cure polyester and resin, and as he recalls, “Jack was endlessly open and generous and engaged—he was just so curious.” Ron Cooper was wrestling with fiberglass, and presently lasers; Guy Dill with strapped sheets of glass, and his brother Laddie was looking for a lighter material with the physical quality of concrete to deploy in sculptural combination with slicing panes of glass, got that, and in the process got a whole new concrete-like material for painting with as well. Larry Bell got help metal-plating vast standing panes of glass for a show up in Santa Barbara (“Jack contributed enormously to the viability and the use of materials across our entire community,” Bell once told me. “He was able to translate highly technical data into language that could be useful for artists. And besides, the guy had a great sense of humor—the goofier the idea, the more he seemed to like it.”) Ed Moses needed help achieving a series of identically even monochrome finishes across a sequence of large square paintings. Tony DeLap did a lot of his own work, but relied on Jack for the installation of his major public installations, like that magic Big Wave gateway arch over Wilshire as the boulevard enters Santa Monica. Chris Burden had Brogan engineer the erector set components of his model bridges. Lynda Benglis was trying to figure out how to render a series of knotted cloth pieces more permanent, perhaps by bronzing them, and instead got introduced to a new spray process whose nozzle spewed out a metallic mist at 4,000 degrees (in the end, once the pieces were buffed and polished, all that would be left was the part that Jack had worked on). Which is not even to mention the swirling cardboard furniture he (and to a lesser extent Irwin) invented and Frank Gehry presently hijacked for his own, to Brogan’s massive financial detriment. (Brogan still has the original prototypes and all the diagrams for their manufacture—but that’s a whole other story and probably deserves an essay of its own.) Sometimes Brogan only consulted (at one point he was even awarded an NEA grant to do nothing but that); other times he would end up fabricating virtually the entire piece in question.

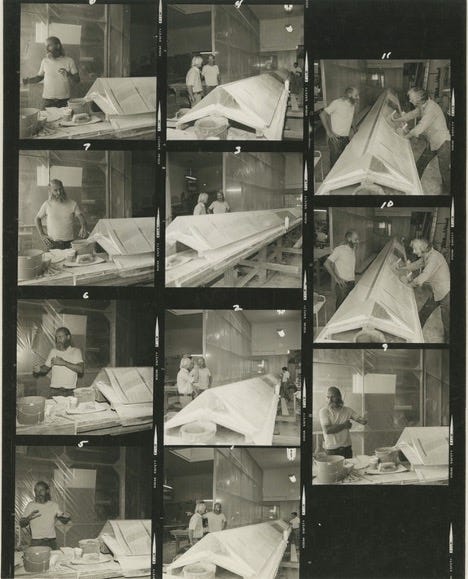

Helen Pashgian, a Pasadena-born art historian, had matriculated at Pomona and Boston College and was on the verge of launching into a Ph.D at Harvard (with a focus on the light-besotted painters of the Dutch Golden Age) when she veered into art-making instead, in the process returning to Southern California and presently becoming one of a group of artists in residence at CalTech exploring the expressive potential of the sorts of resins the aerospace industry was fast pouring forth. A couple days before the opening of an exhibition given over to the group’s work, she was becoming increasingly frantic as she endeavored to complete the finish on an extraordinarily ambitious freestanding 60-inch transparent clear polyester resin disc that she’d cast herself, and, as she recently explained to me, “My fellow artist-in-residence Peter Alexander suggested that maybe I’d better go talk to Jack, who I’d never heard of at the time. But I did, drove all the way crosstown to his studio on Lincoln—there he was, this tall lanky guy in blue jeans and a denim shirt with a premature mop of grey curls and this lilting Southern accent, completely open and approachable, and he listened thoughtfully and then suggested that maybe he’d better come back with me to CalTech to pick up the piece and bring it back to his studio, which he did, it took five guys to hoist the thing onto the back of his truck, and I followed him back—and the thing was, he got it, he just understood the exigencies and the emergencies of an artist’s life, and he stayed up all that night, sand-polishing the thing with water hoses and hand pads, and then hauled it back to CalTech the next afternoon just in time for the opening. And never even charged me. But the results were beautiful, so clean and smooth and gleaming”—so beautiful, in fact, that the piece was stolen clean out of the show a few days later and never seen again!—“but I decided … I mean, I liked to think of myself as self-sufficient, was already doing all my own casting, but it was obvious that this guy had an eye like no other and hence a lot to teach, so I started driving cross town a couple days a week just to work on my smaller pieces there in his presence, and to listen in as the other artists would come by to talk with him, and especially the conversations between him and Bob Irwin, who seemed to be there all the time.

“In particular I wanted to learn how better to polish my surfaces. He told me that the surfaces I made were shit. Whereas I thought, notwithstanding that one moment of panic, that they were already pretty good. So he said he would teach me how to do it, and then he would go off and do other things for a while and occasionally come back and check in on how I was doing. I was working with those same hand pads and water tubes and after a couple of hours, he’d amble over, and you know how he has those big hands, he would take the palm of his hand and he’d go like this and smooth off all the water and then get down, way down, and he’d peer at the thing from the side, and he’d say, in his wonderful Southern accent, he’d say, ‘Not good enough.’ I’d almost groan in exasperation: ‘Jack, that's the best I can do.’ And he’d say, soft and gentle, ‘No … it’s not the best you can do.’ And then he’d float that famous phrase of his, he’d say, ‘Make it niiiiice.’ He's the only person I ever knew who could stretch the word ‘nice’ into three syllables: ‘Make it ni-iii-ice.’ And I’d throw myself back into the work, and eventually, maybe, he would say, ‘Okay,’ which was the highest praise he would ever give and by that time was hugely satisfying praise indeed.”

Pashgian paused, smiling, before concluding, “In my earlier life, I’d been lucky enough to study with some of the greatest academic art historians and theorists of that era, but I can honestly say that, in a really important sense, it was Jack who taught me to see.”

Around the same time (the late ’60s and early ’70s), Robert Irwin was approaching “point zero” in his own successive dematerializations of the art object, trying, for example, to come up with a piece that might flash, gleam-like, out of the corner of a passerby’s eye but would disappear almost completely if gazed upon directly (again, that insistence on perception itself, perceiving oneself perceiving, as being the true subject of art), and at a certain point he hit upon the notion of creating a series of slender, precision machined, vertically mounted acrylic prisms. The machining was not that hard a challenge for Brogan, but the trouble was that the high-quality transparent acrylic slabs out of which they were hoping to carve the prisms only came in lengths of four feet, whereas Irwin was aiming for eight-, and presently sixteen-foot-high columns—and how on earth were they going to join the various slabs seamlessly, such that there wouldn’t even be the slightest hint of a horizontal suture? “That one kept me up all night, trying to formulate the bond,” Brogan recalls—the novel process he eventually came up with involved neither glue nor heat but rather “solvent welding,” slathering solvent on both tips and then subjecting their joining to pressures in excess of 35,000 pounds per square inch (and that wasn’t even counting the weeks and weeks of buffing and polishing that then had to ensue). In the end, Irwin presented Brogan with the challenge of achieving one such jumbo column that was over 30 feet tall. By the time that one got installed in the Northridge Shopping Mall in 1971, the piece (“as clear as a contact lens”) was the second largest optical device in all of Southern California (right after one of the mirrors at the Mount Palomar observatory), and a couple of decades later, when the 1994 Northridge earthquake utterly flattened most of the surrounding shopping center, the prism emerged still standing, sovereign and unscathed. (Today it graces the Federal Courts building in San Diego—a metaphor for justice perhaps: now you see it, now you don’t.)

*

According to Margaret Honda, who scrupulously tabulated the particulars in her dissertation, by 1967, 10 percent of Design Concept’s billable hours (albeit at a much less substantial rate) were being logged to artists, with the lavish profits from Jack’s work with higher-end clients going to cover the difference, and in particular allowing him to devote a substantial portion of his time to pure research, to stocking his workshop with the most-up-to-date equipment (“I wanted to get my shop to the point where I had everything I needed to do anything I might want,” he told Clarkson for his documentary), and to training a long term cadre of presently expert artisan-assistants (the plurality of whom, as time went on, would hail from Mexico or Guatemala, though he himself spoke not a word of Spanish). He never promoted himself, he explained to me, “because if you advertised, you were honor-bound to take on anybody who came through the door, which I didn’t want to have to do. It was all word of mouth. And I kept time-cards on all the jobs I did, because I wanted to make sure I wasn’t charging too much.” Not that that was ever much of an issue with the artists in those days, few of whom had any money to speak of anyway. “I could have made a lot more money, I suppose,” he acknowledges, “but I wouldn’t have had nearly as much fun.” At any rate, according to Honda, by 1975, the year Brogan transferred his operation down to San Pedro (for what would prove to be the next couple of decades), the proportion of his labors given over to art projects had ballooned closer to 85 percent.

For one thing, there were fresh new artists constantly calling on his studio: Robert Thierren, Alexis Smith, Chris Burden, Bruce Nauman, Dan Flavin, Lisa Bartleson, and countless others. One veteran in particular, John McCracken, who’d already made a considerable name for himself fashioning sumptuously color-saturated plinths (featuring layer upon layer of high gloss paint and sanding and polishing, all of which the artist himself had rendered by hand), commissioned Brogan to execute a fresh series of such plinths, from provided diagrams clean through to completion, this time with a skin of exquisitely mirroring stainless steel. In order to avoid the slightest surface distortions (which would have led to unfortunate funhouse mirror effects), Brogan had to invent an entirely new polishing protocol. At one point, after he and his assistants had subjected one column to 15 rounds of sanding and burnishing, McCracken dropped by and was completely floored by the result, but Brogan harrumphed as to how he was pretty sure he could make it better still, and proceeded to lavish a further 20 rounds of polishing. (Each of the ensuing plinths ended up requiring upwards of 80 man-hours of finishing to complete). Granted, other efforts weren’t quite so time-consuming. When John Eden dropped by to ask how he might achieve more of a frosted effect on the perfectly transparent glass cast he had recently made of Larry Bell’s hat, Brogan told him, “Easy. Sandblast it with baking powder.” And when Peter Alexander asked how he might achieve a brighter shine on his own teeth, without missing a beat, Brogan responded “Just mix grapefruit seed extract into the reservoir of your hydraulic toothbrush.” (Alexander laughs at the memory of that one: “It completely figures that Jack would know that.”)

And with each passing year, more and more of his practice involved the conservation and restoration of earlier pieces by many of the artists he’d been working with from the beginning. This was especially the case with work they had completed in the days when they first took to experimenting with the various urethanes and acrylics, and before they’d quite mastered the stabilization of the novel media’s color or texture. But in addition, the works were often inherently fragile, and they were regularly getting scratched and nicked, to often devastating effect, so collectors, gallerists, and curators began to call on Brogan, who alone, thanks to his preternatural command of materials, but also to the fact that the practices in question had often come into being under the thrall of those endless schmoozing sessions in his very workshop, seemed able to work wonders with repair. He figures that over the years he has restored a hundred McCrackens, somehow managing to match the layers of often mislabelled paint. (“The sales catalog might list it as a polyester when in fact it was a lacquer or an acrylic and in any case, the color had faded or else was no longer being produced, so I’d have to track all that down and compensate accordingly.”) Larry Bell’s glass cubes were regularly fogging over, or their subtle skins discoloring, especially if they were subjected to the pressure changes of being flown from one collection to another, and in order to affect those fixes, Brogan had to figure out how to pry apart panes that had been sealed years earlier with arcane epoxies or even simple airplane glue. (“Dental floss,” Brogan averred, self-evidently, when I asked about that particular maneuver.) Other pieces would just get knocked off their pedestals and shatter, and then it was a question of finding exact matches for the glass and retro engineering the coating methodologies, as if from scratch. (During one visit to the studio, I spotted, leaning against a wall, one of less than a dozen extant Irwin acrylic discs, jaggedly mangled clean in two. “Ahhh,” Brogan reassured me when he noticed the look of anguished dismay crossing my face, “don’t worry, we’ll save her.”) DeWain Valentines, Craig Kaufmanns, that great lifesize Charles Ray red Tonka fire engine, which had returned from Germany where it had been given by a collector to his kids, who’d thoroughly shredded the thing (in this instance, Brogan’s twin loves for refurbishing cars and restoring art quite literally overlapped). But not just the California artists: an Ellsworth Kelly from the Norton Simon Museum, an Alexander Calder stabile warped in a house fire, a Henry Moore marble (across whose repair he deployed a quiver of dentist’s probes, and no, I don’t know what the deal is with Brogan and teeth), and even a Brâncuși, perhaps his single favorite grand master. But those other masters aside, I can’t tell you the number of California artists and curators and gallerists who, when I brought up the name Brogan, literally cringed at the prospect of his imminent retirement. Whoever was going to be able to care for much of the work of the past half century once he was no longer going to be available? Who would have The Knowledge?

In addition to that sort of studio work, Brogan’s practice began to branch out in other directions as well. For one thing, several of the artists he was working with were starting to engage in far-flung, often site-specific, installations, and Brogan began traveling the country and even the world (as with that Turrell in Amsterdam, and Doug Wheeler’s contribution to the 37th Venice Biennale in 1976), supervising the execution of their ever more ambitious designs. In Irwin’s case, for example, figuring out how to span the entire fourth floor of the Whitney in New York with a 114 foot long, 2 inch thick black-painted steel bar suspended at eye level and supported, along its entire length, by nothing more than a swath of white scrim suspended taut from the ceiling; but then as well a vertical grid of square scrim light-catching panels hanging down through the vast central atrium of the NEA headquarters in Washington, DC (formerly the central post office, eventually to be the Trump hotel); or vaulting banks of fluorescent bulbs cantilevering out over the yawning open interior of the University Art Museum in Berkeley; culminating eventually in some of the key components of Irwin’s master plan for the Central Gardens at the Getty in LA (notably including the exquisitely designed bronze lamp posts and the pinched rebar flares of the bougainvillea arbors), and on and on.

*

And yet for the longest time, nobody outside the immediate art world even seemed aware of Brogan’s existence, let alone the extent of his contributions. Brogan once commented to me on how zealously many of the artists insisted on his safeguarding the processes he was innovating with them from all of their colleagues—there was a great sense of proprietary knowledge (not unlike the competitive situation of the trailblazing oil painters of the 15th century, is how someone else characterized the situation), and Brogan’s reliably reticent discretion was one of the things the artists most came to prize in him.

But more striking, for the longest time, was how hesitant artists were to acknowledge Brogan’s contribution in the creation of their own work (to this day, with regards to many of the artists I interviewed for this profile, I can’t count the number of times someone would remark on how absolutely essential Brogan’s contribution had been to everybody else, just not so much for them personally). Artists would regularly explain to interviewers how they themselves had done this or that when in fact it had been Brogan and nobody but Brogan who had actually done it. Sometimes artists would wind themselves into pretzels of arcane artspeak in order to avoid acknowledging the obvious. Thus, for example (and I don’t mean to single him out as particularly egregious, so many of the artists were spewing forth similar sorts of arch gibberish), the late Ed Moses once characterized his square monochrome paintings as the “conceptual ideal of an abstract painting, existing in a two-dimensional plane. They are not painterly paintings, not painted by hand. They are the physical evidence of an abstract painting as a physical phenomenon.” Which, okay, was fine as far as it went, Moses indeed hadn’t laid a hand on them, but they had been painted, painstakingly so and in an entirely innovative manner designed to achieve that specific uncanny aura, by Jack Brogan. (“Yeah,” Brogan admitted, with a certain joshing pride when I brought up the particular instance of those Moses monochromes with him, “and I never told a soul that it was me that had done them, not for over 25 years.”)

Quite often, for example, he would work on pieces right up through their gallery installation but then not get invited to the opening, or if invited, not get acknowledged or even included on the guest list for the after-dinner. And, Brogan’s aw-schucks deference notwithstanding, it had hurt. “It’s not that he didn’t respect the artists,” Edith commented to me confidentially at one point during our Santa Monica conversations, when Jack had gotten up to tend to some business matters out back. “He wouldn’t have worked with them to begin with if he hadn’t, and he liked them. It would just disappoint him when they would take credit and even win awards for innovations that were his, and they wouldn’t even invite him to the openings, as if they wanted to hide his very existence, how they just could not share even one percent of anything to do with it. And the cumulative effect of decades of this sort of thing gradually took its toll.”

I asked her how he dealt with it. “Well,” she replied, “he’s the quintessential southern gentleman, as we all know, and he was never going to be a rabble-rouser. He doesn’t have the kind of personality where he has to pretend that he’s more than he is to prove that he’s a great man. He is thoroughly sure of his expertise and his value. He is very much his own man.”

And has had to be since he was seven or eight, I suggested.

“Exactly, and in any case, he’d always be on to the next thing. He doesn’t brood. He was always less interested in getting credit for the last thing, so interested was he in forging on ahead into the next one, in confronting its challenges and inventing those solutions… ”

I was reminded of Diderot’s discussion of that extraordinary moment in the gestation of the occasional masterpiece when the artist stops asking, “What can I do?” and starts asking, “What can Art do?”

“Exactly, except that he, Jack, rather than the artist in question, was so often the one who was actually doing it. But yes, his true involvement was with the material itself, with the marvels of what it could be made to do, how it could be made to do it, and how much further that process could be pushed, he was always more interested in that than in anything as inconsequential as credit or reputation.”

Brogan had drifted back into the room and shuffled over to his seat: he was clearly uncomfortable with the tack the conversation had taken in his absence, but he let Edith continue a bit further (this was evidently an ongoing topic in their marriage), before interceding, “I was always using the artists’ projects as a way of testing and furthering my own technique.”

*

“Making the real real is art’s job,” Eudora Welty once declared. Brogan’s job, for his part, was actually realizing an entire generation of artists’ ideas as to what needed to be made evident.

One day I was asking Peter Alexander whether he had any thoughts as to why Brogan hadn’t aspired to be an artist himself. “It wasn’t even in his vocabulary,” Alexander suggested. “Coming from where he came from, it would not even have occurred to him.” I pointed out how Ed Kienholz and Ed Ruscha, for example, had emerged from backdrops no less improbable. “Well, yeah,” Alexander paused, mulling. “Maybe Jack just didn’t have the ego. Unlike the rest of us, who were the most ego-driven lot you could imagine.” That certainly seemed right, especially when you compared him, say, to Kienholz, who emerged from out of that almost identical upbringing (though in Eastern Washington state, in his case): a full blown ego-maniac. (“Just a quarter turn of the screw,” Irving Blum, the gallerist and Ferus veteran, once summarized Kienholz for me, “just a quarter turn, I’m telling you, and we could have had Adolf Hitler all over again!”) “But maybe that sort of ego is something that all artists have to have to some degree,” Alexander hazarded, “just to be able to keep going. Whereas Jack is virtually egoless, in fact he is the very embodiment of an almost Zen-like egolessness.” (A comment which in turn reminded me of something Blum once told me about how the young Bob Irwin was the most ambitious artist he had ever encountered; when I pointed out to him how that seemed a strange thing to say, given that the Irwin of those years was so deeply involved with Zen, Blum shot back, “But Bob Irwin was dealing with Zen in the most aggressive way Zen has ever been dealt with!”) “Still,” Alexander concluded, “even though he wasn’t one of us, Brogan found us egomaniacs fabulous. And, actually, to tell the truth, as a fabricator, Brogan was an artist.”

Irwin would likely concur with that appraisal. At one point he told Margaret Honda, “The way Jack works is like an artist; he processes information the same way. His is a tactile, hands-on knowledge.” Tactile being a key word in the Irwin lexicon. He used to describe for me how back in the days when he was earning his livelihood playing the horses, there would obviously be a place for logic, for all the sorts of quantitative information one could extract from the Racing Form, but then something more was always required. Before placing his wager, he described how he would run his hand over the whole coming race in his imagination in an attempt to get the feel of the thing, and only then would he lay down his bet. Which, he acknowledged, was the same with his art. And for Irwin to credit Brogan with that way of engaging the world, coming from him, was high praise indeed. (Talk about the Dialog of Imminence!—another of Irwin’s favorite constructions.)

When I subsequently asked Brogan himself why he hadn’t tried to be an artist, however, his answer was more straight-forward. “I didn’t want to pin myself down,” he said. “I looked at those guys and they were always doing the same thing, over and over, with slight variations, for years on end, whereas I always wanted to be moving on to entirely different sorts of challenges.”

*

For the longest time, Jack Brogan’s reputation, to the extent that it existed at all, seemed to shimmer between rumor and legend, shading ever so gradually towards the latter in more recent years. And indeed, with the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time citywide celebration of the taproots of Los Angeles art, back in 2011, Brogan’s contribution finally began to edge into the wider art public’s awareness.

Indeed, it is has been becoming increasingly clear since then that in the years ahead, the very history of art in Southern California may need to be redrafted—with so much of the so-called Finish Fetish of ’60s and ’70s LA art (a facile sobriquet that, granted, they all resented, though everyone recognized the exactingly precise aesthetic to which the term referred) being seen to come down, not so much to the car or surf or aerospace culture to which it usually gets ascribed, or even to The Light, but rather to the commanding influence (either directly by way of actual manufacture or indirectly by way of towering example) of just one man, so much so that now, with that fast approaching retirement of his, past age 90, a veritable era may be seen to be coming to a close: the Era, indeed, of Jack Brogan.

*

Except that—news flash: hold on!—I spoke with Jack just as I was originally putting this piece to bed, and it turns out that he’s decided not to retire after all. He’s simply moved his workshop to a site closer to the Santa Monica home he shares with Edith, and he’s already back at work.

To which a quick survey among local arteratti has elicited three sorts of response: 1) Pfew! 2) Thank God. And 3) from Peter Alexander (who in the meantime has himself passed away, this being the very last thing he said to me on our very last telephone conversation): “ 'Figures.”

A significantly condensed version of the above profile is appearing this fall in the catalog for a touring show of work from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Light, Space, Surface: Art from Southern California (DelMonico Books•D.A.P. and LACMA, 2021). This piece was previewed, in its entirety, in last month’s Brooklyn Rail online.

* * *

A-V ROOM

IN CONVERSATION WITH KEN GONZALES-DAY ON THE HISTORICAL REALITY AND ARTISTIC REPRESENTATION OF LYNCHINGS

“Most of all, beware, even in thought, of assuming the sterile attitude of the spectator, for life is not a spectacle, a sea of grief is not a proscenium, and a man who wails is not a dancing bear.” --Aimé Césaire

Over the past several decades, Los Angeles-based photographer Ken Gonzales-Day has been engaged in one of the most trenchant and consequential explorations both of the historical reality of lynching and of the aesthetic and ethical complications involved in blithe latter day cultural appropriations of incidents which from the very start had been cast as prurient spectacles. Several years of archival research culminated, in 2006, with the publication of his Lynching in the West (1850-1935), which revealed the shocking and long-occluded extent of extralegal executions not only of blacks but of Latinos and others as well, particularly in California. This research in turn informed several subsequent projects, including one in which he compiled often hand-tinted vintage postcards celebrating local lynchings and then proceeded to honor the victims by airbrushing them out of the image entirely, inviting viewers to focus instead on the obscenely gawking spectators, and another in which he travelled all around the west, prizing gorgeous Ansel Adams-style photos of stately gnarled old-stand trees, which the viewer is only gradually given to understand had been deployed years ago as the site of actual lynchings. Ken Gonzales-Day is chair of the art department at Scripps College and is represented by the Luis de Jesus Gallery in Los Angeles, though his interdisciplinary and conceptually grounded projects have been displayed throughout the world. In 2018, Gonzales-Day’s work was featured in “Unseen: Our Past in a New Light,” at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. He is The Fletcher Jones Chair in Art at Scripps College and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in Photography in 2017.

For more on Gonzales-Day go here, and to watch their recent Zoom conversation, from the Weschler-curated series with Arts Letters and Numbers at the Venice Architectural Biennale, go here.

* * *

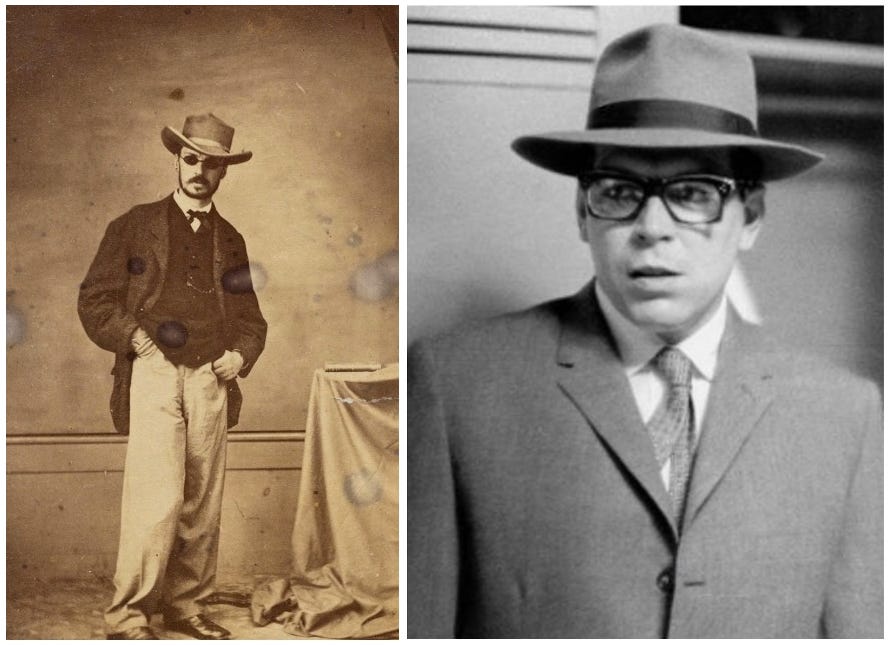

From time to time we will consider things that are wildly divergent and yet seem oddly alike and wonder what the hell is going on in each specific instance. This time though we will consider two photographic portraits and ask you, simply, just who are these guys? You’ve likely heard of both of them. A thousand points for anyone who guesses both. Answers in two weeks.

A GUESS-WHO CONVERGENCE

World Travelers Edition

Two clues: The portraits were taken exactly one hundred years apart, in two separate places in Latin America.

Please send your guesses to weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com — with the subject line GUESS-WHO CONVERGENCE.

* * *

In the months ahead, as I keep mentioning, I will be publishing a new book, regarding which, further details anon. In the meantime, there’s this:

YET ANOTHER FOOTNOTE FROM A BOOK YOU DON’T HAVE TO HAVE READ, OR EVER READ

Footnote #8

And what kind of name is Shimmel anyway? Sounds like Schlemiel and, by way of schlemiel, seems to summon forth the entire Yiddish lexicon for pathetic losers of all sorts—the schlimazls, the shmendriks, the klutzes and dummkopfs and nebachs (origin of the Yinglish nebbishes) and yutzes, the doufusses and the schmeggeges, and on and on, in all their sublime glory.

Actually, no, though: it turns out that “Shimmel” is simply the diminutive of “Shimon,” an entirely unobjectionable appellation. But still, the first time I heard it, the name immediately reminded me of a conversation I had with Cheryl, a delightful Italian-American girlfriend I had for a few years just out of college (I taught her guilt, as we used to say, and she taught me shame), and how one time I was trying to explain to her the ever so subtle distinction between a schlemiel and a shlimazl (how if you happen to be at a party and you see one fellow spill the onion dip all over another, the one who does the spilling is the schlemiel and the one spilled upon is the schlimazl) which led into a wider celebration of all the exquisite nuances that Yiddish affords for all the different types of loserhood, whereupon she interrupted me to inquire, self- evidently, “Oh, so is that like Eskimos and snow?”

* * *

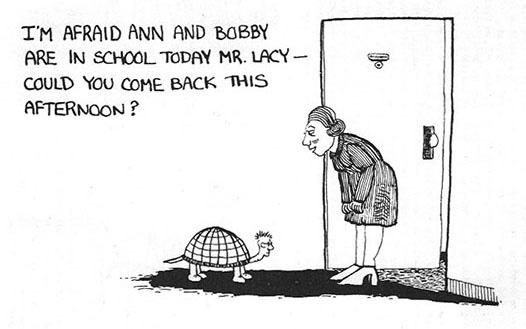

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Coming in two weeks, an extralong footnote on ghosting and erasure, from DeKooning through the Death of Stalin; the surprising answers to this week’s Guess-Who Convergence; a Zoom conversation with artist/celebrator of otherwise invisible domestic workers, Jay Lynn (formerly Ramiro) Gomez; speaking of ghosting, Ghostcubes!; and Ren’s toddler goddaughter says the darndest thing…

Please take a moment to subscribe, and a new issue of Wondercabinet will appear in your in-box, absolutely free, every other Thursday.