WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This week, a continuation—part two (of two)—of our profile of the young Italian-born American video art phenom Federico Solmi, in the midst of his big current retrospective at the Morris Museum in Morristown, New Jersey; a supplemental subsequent visit with him to survey his hometown Bologna roots; concluding with a final political bagatelle regarding the upcoming Saudi appropriation of the notorious “Trump Links” municipal golf course in the Bronx…

* * *

The Main Event

Federico Solmi: The Butcher’s Son

(PART TWO, of two)

On the occasion of the recent opening of his big mid-career retrospective Joie de Vivre, through February 26, at the Morris Museum in Morristown, New Jersey (an easy hour’s train ride out of Penn Station in Manhattan), the Wondercabinet herewith concludes its two-part serialization of Weschler’s biographical sketch of the artist Federico Solmi. Those of you who were with us last time out will already know the story thus far (the rest of you can dip back to that issue), but in broad summary, Federico, born into a working class family in Bologna, Italy—his father a butcher, his grandfather a steelworker—was the first in his long line even to complete high school and had had every intention of going on to study art at the town’s storied University (the oldest continually functioning such institution in the world) when his father’s heart attack forced the boy to renounce such plans and instead return to the family butcher shop. He pledged to thus devote himself to the family’s wider welfare, across a grueling and almost all-consuming work schedule, for the next seven years (that is, until his youngest sister turned eighteen), and indeed did so—though he contrived to let it be known in the local art community that he would set aside choice pieces of meat at discount prices for any who would drop by the shop and engage him in conversation about the history and practice of art, and many did. Steeped in this remarkable if decidedly unorthodox education, in 1999, at age 25, Solmi lay down his blade and travelled to New York to seek his fortune. Which is where, stepping back a paragraph, we resume the tale:

Based now in a tiny one-room apartment at 10th Avenue and 34th that he was sharing with one of the Dominican guys working for the Taxi dispatch center downstairs, Federico began frequenting museums and galleries and, for student visa purposes, classes at the Art Students League, where the benign tutelage of a sculpture professor who happened to be the son of Ben Shahn proved particularly heartening. Still, a complete outsider, albeit a strange one (one steeped, that, is in the entire tradition of the High European Renaissance, none of which seemed to hold any particular sway or purchase in the frantic hothouse atmosphere into which he’d suddenly alighted)—how was he, an uncredentialed butcher’s son and a longtime butcher himself, newly arrived in a town, as he quickly noted, where all his same-age competitors seemed to have just emerged from the likes of Yale’s graduate MFA program—how was he, with no connections, no entrée, no letters of reference, and an at best rudimentary grasp of the language, ever going to breach the scrupulously defended ramparts of the established art world? All he had was his discipline, his ambition, his evident eagerness, and his sheer—how does one say chutzpah in Italian?—his sfrontatezza, his audacio, his baldanza, his ardimento. That audacious ardor of his.

“And oh,” he interrupted himself the day he was telling me this part of his tale, “I forgot to tell you about my trauma.” His trauma? “Yes, how when I was only fourteen months old, poking about our apartment one day, exploring, I unscrewed a light bulb from a household lamp and wedged my entire left hand into the 220 volt socket, just to see what would happen, with results you can hardly imagine. I was rushed to the hospital where the surgeons were getting set to amputate the whole mangled thing, but my mother wouldn’t let them and instead ferried me over to a hand clinic in Modena, where they initiated the first of what would prove to be literally dozens of operations over the years ahead, methodically reconstructing the hand, bone by bone, knuckle by knuckle, taking all kinds of skin and muscle grafts from my back and legs and so forth. I have completely repressed the physical pain involved, though what I do remember from the last of those operations, when I was eighteen, as they were making transverse cuts into the bloated meat of my fingers so as to re-enable their flexibility, was the smell, good lord. That and the emotional pain—the embarrassment, the relentless teasing (not only a butcher’s son, but one with a claw!), the fact that I couldn’t bring myself to go swimming for fear of exposing the patchwork of scars all up and down my body: that I remember. My mother for her part used to joke how all the electrical energy I took in that day must still be in me, powering my drive ever since, and maybe she has a point.”

Anyway, six months into his New York residency, imagining he was ready to start producing gallery-worthy pieces and in order to stretch his funds a little bit further, he decided to move to an even shabbier one-room rat-infested hovel over in Jersey City, which came with a ramshackle workshop space in the landlord’s condemned building next-door. But this proved a huge mistake: “I quickly began to lose confidence and hope. I mean a year earlier, I’d been inhabiting a glorious mezzanine space in a fresco-lined downtown Bologna palazzo that I owned, in the middle of everything, and here I was, out in the boondocks, not knowing a soul, afraid to go out at night. What on earth had I been thinking?”

But in the first of a series of lucky breaks, somehow he managed to extract himself from that arrangement, relocating to a small apartment in the Dumbo section of Brooklyn, where everything was different. Suddenly he was surrounded by other would-be up-and-coming young artists (one of whom, for example, taught him how to stretch canvas: he’d had no idea), and others who engaged him in vivid artworld and political conversation. His brother back in Bologna, who was managing his money, warned him that it was beginning to run out, so he got himself a job at the Cipriani’s operation on the mezzanine of the Great Hall in Grand Central—first as a busboy, then a barkeep (“the bartender’s bitch,” he explains), and finally as a full-fledged (albeit frantically self-taught) bartender. He was back to working forty-hour-plus weeks, but this was where, on—wait a second, he interrupts himself (embarrassed not to know: he calls his wife for the exact details)—on September 20, 2002, he met Jennifer Anne Bouck, a striking American IT manager (of Irish-English descent) out of upstate New York, and it was thunderbolt love at first sight, evidently on both sides. Within a few months, he was traveling with her back to Ireland to explore her roots. However, he was then denied entry onto the plane back (he had somehow overstayed his welcome on his earlier visa), but hey, no problem, he returned to Italy, Jennifer continued on to New York and packed up their apartments so as to fly back to join him there, within a few more months he had proposed and they were wed, and she got an IT job in Milano,

and, while they negotiated his immigration status, they travelled all around Italy and Sicily, and in February 2004, they returned to New York (him with the proper greencard in hand), to an apartment in Williamsburg. “On one condition,” Federico recalls Jennifer now laying down the law: “‘No more bartending.’ I absolutely had to throw myself into my art full-time. Really,” he continues, his eyes starting to glisten, “I am not exaggerating, that woman saved my life.”

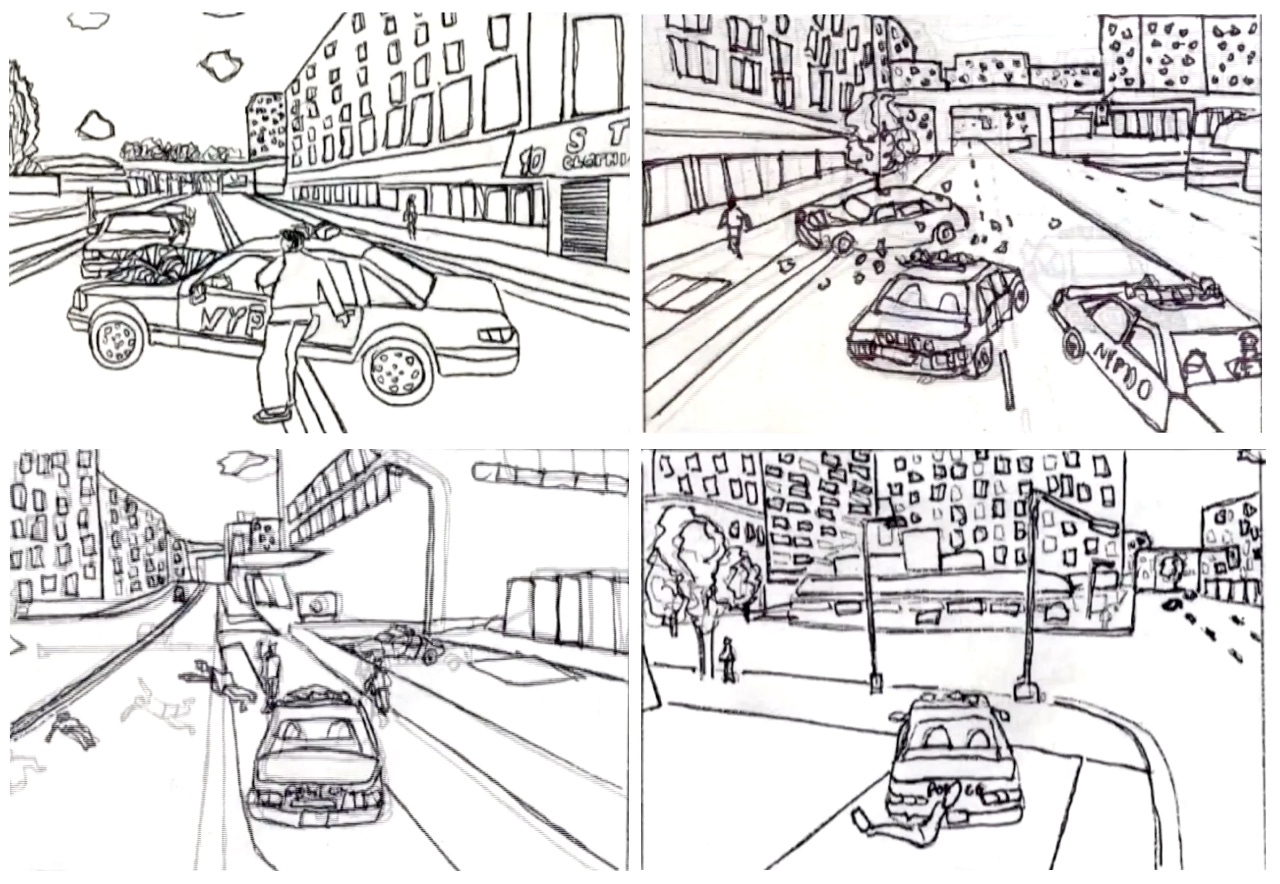

Whereupon he wholeheartedly threw himself into his artistic vocation by immersing himself in the newly released Grand Theft Auto video game, though, he avers in his own defense, in a really serious manner. “Not as a gamer,” he insists, “but I became fascinated by the perspectival dynamics and visual narrative possibilities of the first-person shooter vantage: the world-building potential overlaying all those algorithms. One evening I got Jennifer to videotape the screen as I played a game, racing my way about a streetscape which incidentally was the very streetscape where we were then living: stealing a police car and careening down the streets, skidding and screeching and bouncing off passing vehicles and so forth. I was even changing the stations on the virtual radio dial! And then I found someone, which was easy to do there in Dumbo, who could break the resultant video stream into 350 individual stills, which I then used as the basis for 350 ink drawings—it was crazy, once again I was working night and day—all of which…

The thing is that from the very start I realized that these new digital media held all sorts of promise, but they were cold, inhuman, and hence condemned to already feel outdated within months of their release; what they called out for was the warmth of the human hand: this was my Renaissance exposure peeking through and kicking in, the insistence on the necessity of draftsmanship (of mind working through the hand). And by September, I had completed my 350 drawings, rotoscoped them in sequence, and produced my first video, Another Day of Fun, which not long after I showed to a big Italian collector at an art fair, and he bought it on the spot, the 350 drawings and the video, for $12,000. So I was running and off.”

While working on Another Day, Solmi began to wonder what it would be like if he could build his own assets, which is to say (de Chirico-like) to fashion his own stage sets and, in the manner of the great fresco painters, to model his own characters, storyboarding an entire narrative and, by deploying Maya software and with the assistance of a professional game designer he began working with named Russell Lowe, to be able thereby to lay an entirely fresh look over the standard gaming algorithms.

Across the remaining months of 2005, in fast succession, he produced three such rotoscoped pieces (requiring 2000 ink study drawings in all), two grouped around the adventures of an over-the-top porn star named Rocco Siffredi (it figures, of course, since it seems like every new burgeoning technology tends early on to indulge the pornographic—although in the second of these, as the titular stud was filming his latest masterpiece Rocco Never Dies, he suffered a massive heart attack and ended up dying, the story veering into the much more personally loaded terrain of Solmi’s own father’s death).

Following which, the young master perpetrated his most ambitious effort to date, an uproariously savage five-minute satirical assault on the intertwined worlds of art and finance, King Kong and The End of the World, in which the towering lumbering great ape, sporting a huge red-knobbed joystick erection (for Solmi was also beginning to introduce color by way of markers and dabs of acrylic), ran roughshod over Wall Street, flinging brokers pele mele and all about; then careened uptown to uproot the Guggenheim Museum which he proceeded to lug back downtown (beef-carcasslike) so as to slam the thing onto the Gagosian Gallery, over and over again; whereupon he challenged the Statue of Liberty to an epic wrestling match in the middle of Times Square (brandishing the golden arches of McDonalds as a cudgel), and on and on.

(“Gee, Mr Solmi,” a viewer might well have been given to inquire, “how do you really feel about things?”)

But Solmi’s experiments began to register as small sensations of their own. “And it’s crazy,” he commented after showing me the Kong short on his laptop, “within just a few years, the Guggenheim and Times Square….” He let his voice trail off.

Over the next few years there ensued a trio of ever more ambitious, innovative, and labor-intensive projects, one hard upon the next (for clearly, sheer physical stamina—la resistenza, il vigore—had been another of the legacies his years in the butcher shop had lavished upon young Federico). First off, The Evil Empire (2007-8), a scathingly sacrilegious satire on the Catholic Church from Crusader times (replete with conspicuous echoes of Uccello’s rampaging horse armies) on through the reign of a future pope who gets portrayed as a wildly profligate drug and sex addict who, by the last third of the film, ends up in hell.

This four-minute single-channel video was rendered entirely in color—ink and markers during the first part but liberally slathered acrylics across the final third, and indeed here for the first time Solmi dispensed with his painstaking rotoscope page-by-page drawing technique and experimented with a new method. He produced detailed “skins”—painting over every surface of building or ground or sky in the backdrop, and then wrapping the figure of each protagonist in a 360 degrees of individually painted flat swaths (separately rendered head, face, shoulders, arms, hands, fingers, torsos, legs and so forth), which when integrated by the computer program ended up creating a 3-D figure that could subsequently be guided through its paces across the similarly tracking backdrops by way of mere joystick manipulations. From now on out, every figure in Solmi’s videos would receive its own brace of individually rendered “skins,” which, when spread out across a long table as they dried, resembled nothing so much as the fresh-cut offerings behind a butcher’s counter (and when subsequently gathered together between covers, a separate volume for each character, would form the basis for a library of rococo splendors).

In this particular instance, however, Solmi’s over-the-top fantastical projections got him in trouble: when the video was shown in Italy, the piece itself got arrested, with the artist indicted on obscenity charges, leading to proceedings (and scandal-scale media coverage) that lasted months and only got suspended, at length, when the cultural attaché of the Italian consulate in New York cabled the presiding judge to ask what the hell they thought they were doing, this was one of the country’s most promising young artists they had in the dock.

There followed Douchebag City (2009-10), another coruscating satire, this one consisting of fifteen short videos running simultaneously across an array of small, antique-framed monitors grouped about a wall, following the debauched career of an avidly greedy broker named Dick Richman through his own eventual descent into a Dantaesque hell.

With this outing, Solmi was sluicing his various handmade 3D assets through their most video-game first-person-shooter style paces yet. (He was now also starting to employ a studio full of part-time programming assistants.) The piece premiered to considerable acclaim at a big group show of such video experiments at SITE Santa Fe, right alongside a piece by one of Solmi’s greatest idols, William Kentridge. And it was indeed around this time that Solmi received word that less than five years after he’d perpetrated Kong’s slamming of the Guggenheim Museum into the Gagosian Gallery, he was being awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.

The folks at the Guggenheim had awarded Solmi $40,000 toward his next extravaganza (work on which would eventually cost him $200,000): a dazzlingly cinematic three-part wide-screen mini-epic animation entitled Chinese Democracy and the Last Day on Earth, featuring a cast of thousands, lumbering files of tanks, Riefenstahlesque rows of green-uniformed Chinese soldiers goosestepping their way into Manhattan while trailing helium balloons of the dear Chinese leader, and eventually the conquering hero himself, a character upon whom Solmi lavished his first primitive stabs at motion capture technology (deploying his own self as the model).

The Chinese Democracy triptych completed an exceptionally busy and productive phase of Solmi’s career, but have I mentioned? at the same time, somehow, he’d once again become subsumed into another mammoth self-educating reading jag. As we have seen, he’d long harbored certain generic leftist sympathies (perhaps owing to the fact that notwithstanding his family’s relative lack of interest in politics—they were all too busy just getting through each day!—Bologna itself had long been known as The Red City, wending back to before fascist times, and during Federico’s youth was still ground zero for the Italian Communist Party’s brand of Eurocommunism, the so-called Gramscian “Marxism with a Human Face”). All of that perhaps helped account for the default disdain for rapacious stock brokers and high-end art moguls that the young artist so copiously displayed across his early videos. But the longer he stayed on in the United States, the more he came to feel the need for a more informed understanding of what was going on politically on this side of the Atlantic, and its historical backdrop. And so he’d been devouring Eduardo Galeano (Open Veins of Latin America) and Jared Diamond (Collapse and Guns, Germs, and Steel) and Howard Zinn (The People’s History) and Noam Chomsky (Manufacturing Consent) and all the sorts of books that reading those books led into. And crucially, Oriana Fallaci, his fellow countryman and the slashing-sly interviewer of Kissinger and Khadafi and all their ilk (talk about butchers!): Solmi was particularly drawn to this passage of hers:

There’s something missing in all writings about power. Very few are able to capture how funny it is. When historians and political scientists examine the horrors that power commits, the suffering it imposes, the blood with which it stains itself, they always forget to highlight the ridiculous aspects of the inevitable monsters and how funny they are, with their ironed uniforms, their unearned medals, and their invented awards.

The day Solmi plucked a xerox of that passage off his desk to show me, he also had a news photo of Khadafi paper clipped to the page:

And indeed, the passage could be said to serve as epigraph to the whole next phase of Solmi’s work, and the photo as its presiding muse.

For that phase, Solmi realized that he would need to generate a whole fresh series of assets (the industry term for fully accoutered and realized video characters: funny how the term itself reduced digital avatars to their monetary utility in the very same neoliberal way that Solmi was attempting to critique the wider society through his deployment of them). Marshalling his studio full of assistants, he proceeded to design over a dozen new characters (each one requiring dozens of preparatory studies and skins, all of which he rendered personally), a veritable rogue’s gallery of buffoonishly preening crackpot tyrants including lavishly colored characters based on the likes of Ramses II, Genghis Kahn, Columbus, Montezuma, Napoleon, Mussolini, Cortez, Bismarck, George Washington (“Destroyer of towns,” as the Iroquois once dubbed him), and Pope Benedict XVI—in short, The Brotherhood, as Solmi took to calling them (all of them male with the exception of Marie Antoinette and the Byzantine Empress Theodora).

By 2015 the entire menagerie was being featured, each by way of his or her own framed video loop, and then together in various fever-dreamt animated interactions (“Once I had created the various assets,” Solmi explains, “I wanted to see what I could do with them”), first in a show at Postmasters in New York (whose website features a whole roster of video instances) and, the following year, in a yet more elaborate exhibition at the Luis de Jesus gallery in Los Angeles, shows that began to garner considerable and overwhelmingly positive critical notice.

“The scratchy lines of Solmi’s distinctive, cartoonish, garishly-hued renderings of the leaders and their surroundings,” wrote Chris Bors in Artforum, “thankfully don’t resemble the polished, rounded forms of mainstream digital animation with their cloying interchangeable characters… (and) the audio tracks of individual works, including distorted national anthems and carousel music, combine to heighten the forced pageantry to comedic levels.” For his part, Christopher Knight of the LA Times, praised the way “eight LED monitors and a room-sized installation for a suite of five more monitors transformed paintings into disturbing video pageants… In the animations, the Brotherhood strut down red carpets to the flash of camera lights, descend imposing flights of stairs and socialize at a magnificent ball on the fashionably gross order of New York’s famous Met Gala. The installation work, dubbed The Ballroom, is set up like a theater, complete with crimson curtains, where our job is to passively gape,” going on to note how “The hypnotic result are garish, puppetlike figures that seem to float through space, rather like Macy’s Thanksgiving parade balloons run amuck. At once thrilling and chilling, the monstrous spectacles are a wickedly funny distillation of modern media mayhem.”

They were all of that, and a considerable advance on Solmi’s earlier productions. Thus, for example, characters seemed to drift from one monitor to the next across the synchronized quintet of screens making up The Ballroom.

Meanwhile there were individually contained episodes, for example, portraying the first arrival of European explorers amid the warm celebratory welcome of curious, open-hearted natives, and how those interactions quickly descended into mayhem and subjugation. Such stand-alone pieces were now getting wrapped in extravagantly painted and thickly impastoed frames (acrylic on acrylic gel) that seemed to bleed into the surrounded animations, creating the effect of Renaissance era paintings come to life. “One needs to look backward for inspiration,” Solmi conceded to me, “but the past dies if it is not brought into the future, and that is what I am trying to do.”

I asked Solmi whether as an Italian he identified with Columbus and he replied, “Sure, alas, absolutely. In fact, the other side of the entire Renaissance period, whose art I so revere, was precisely all that conquest and genocide, and all Europe was implicated.” (The comment of course put me in mind of Walter Benjamin’s famous observation as to how “Without exception the cultural treasures [the cultural critic] surveys have an origin which he cannot contemplate without horror. They owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great minds and talents who have created them, but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries. There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another. A historical materialist therefore dissociates himself from it as far as possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain.” And indeed, across the entirety of his work, Solmi has been a great contra-grain brusher.)

One day I asked Solmi why he hadn’t included Italy’s own clownishly authoritarian Silvio Berlusconi among his Brotherhood rogue’s gallery and he replied, “Precisely because he was back in Italy, and I am now here in the United States, and I had a hard enough time trying to deal with Trump. Believe me, it was not easy figuring out how to make fun of this guy since he was already such a parody of himself.” In the event, Solmi’s solution, The Illustrious Deceiver, his stand-alone 2017 nightmare raucous-romp rendition of the Great-Making leader’s inaugural parade and gala (full of ecstatically cheering crowds, chimping photographers, and waltzing Brotherhood guests) proved to be one of his most trenchant productions to date. When I first saw it in an early group show of artistic responses to the new presidency at Ronald Feldman’s gallery in New York, I was put in mind of James Ensor’s wildly carnivalesque painting of Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889.

(Solmi veritably glowed at the association: “Exactly. He was one of my models.”) And I myself even tried to convince the folks at the Getty that they should borrow the piece and without comment just set it up on an easel right to the side of the Ensor’s proto-surrealist masterpiece, one of the prizes of their permanent collection, but of course such a proposal crossed all sorts of institutional tripwires and never came to anything. (Though I subsequently marveled at how Christopher Knight had made much the same Ensor association in his review of that 2016 Brotherhood show.)

Joining the octogenarian Ronald Feldman’s stable during the final years of his gallery was another of the highlights of Solmi’s life: this after all was the dealer who had discovered Andy Warhol and, later, Leon Golub, another of Solmi’s greatest model-heroes. Feldman presently invited Solmi to represent the gallery at an Armory show, to which Solmi responded with, in addition to several of his animations, a pair of giant twenty-foot-long friezelike paintings, including The Great Debauchery, featuring a head-on view of an approaching array of exuberant galloping horse-backed flag-wielding Brotherhood types, Solmi’s own take on the monumental history paintings of the high European style.

At an even more monumental scale, there during the late teens, Solmi accepted invitations to mount massive outdoor wide-screen cinematically immersive installations, first with The Great Farce, a nine-screen projection animating the entire facade of Frankfurt’s Schauspiel Opera House in an Abel-Gance like exposition of his entire repertory company of stock monsters; and then in a month-long every-night-at-midnight three-minute appropriation of most of the screens in Times Square (the very Times Square to which his Kong had laid waste in that first animation of his, less than a decade earlier) for a mirrorlike reflection of the veritable carnival of consumption taking place immediately down below.

A sequence that then culminated in a video installation at the Flower Island exhibition center in China, reprising The Great Farce in 360-degree wraparound fashion.

While Solmi noted how all three of these pieces were consciously drawing on the experience of those fresco interiors in Ferrara and the like that had so captivated him across his field-trip escapes from his Bologna butcher shop, they also seemed to be presaging the goggled Oculus virtual reality experiments into which he would soon be turning with The Bacchanalian Ones and other such shows. For of course, you just knew all this would all be leading to Virtual Reality (The past, once again, being refreshed and wedged into the future)

And naturally, presently, to NFTs as well. Because: sure, why not? Meanwhile, he’d also taken to teaching at Yale, the very school whose graduates, a bit over twenty years back, had constituted his stiffest competition when he’d first arrived in town.

*

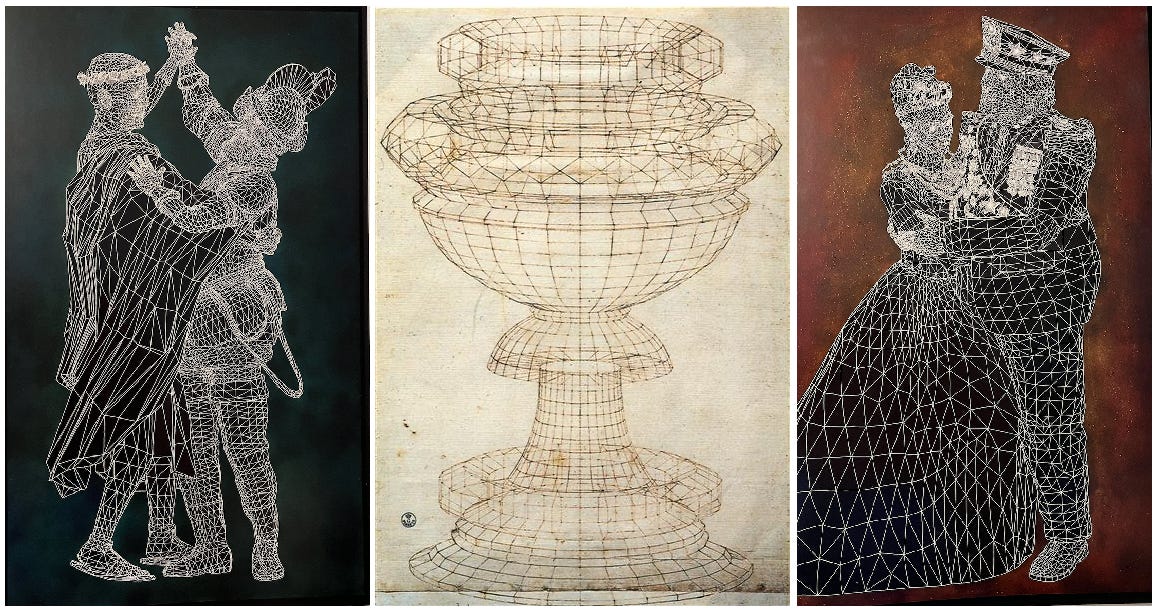

During the two years of relative sequestration enforced by the recent Covid pandemic, Solmi gloried in being able to return to ink-drawing and gouache, to hand-drafting as he likes to say, across a series of full-length 3D-wireframe-style portraits on wood panels of some of his favorite stock characters, alone and in (dancing) groups, in several cases haloed by sumptuous pastel backdrops.

The style obviously owed a considerable amount to the motion-capture graphics animating his recent video efforts, but I couldn’t help but recognize strong echoes as well of that vase diagram of Uccello’s (which, come to think of it, may just be another way of saying the same thing).

The other day, on a visit to Solmi’s northern Westchester home for a remarkable roasted pork and lamb dinner—perhaps not that surprisingly, it turns out that the butcher’s son himself loves to cook, and is very good at it

—I got to meet his wife Jennifer and their two kids, thirteen-year-old Luca and Sofia, eleven (have I mentioned? on top of all the preceding, Jennifer and he have been busy raising two kids). Afterwards, down in his snug basement study, over a shot of good Italian grappa, Solmi related how he figured he was now going to be moving on from the historically based emphasis of his last several years, it was time to start focusing on the present (across the recent drawings he’d introduced a fresh batch of wireframe characters, including William Buffett and Elon Musk and Oprah Winfrey and Mark Zuckerberg and Kim Kardashian) and even more so the future.

It’s certainly going to be interesting to see how Solmi tackles climate change, for example.

But I can’t help thinking that in the years ahead, there’s also going to be an epic beef carcass painting in Federico’s future, and for that matter, perhaps, a portrait of his own hand.

* * *

POSTSCRIPT TO THE FOREGOING

As I indicated at the outset of this piece, over twenty years into his New York artistic career and Federico had never previously publicly confided specifics about the origins of that trajectory in his father’s butcher’s shop back in Bologna. It was all, he insisted, just too embarrassing—though as will have in the meantime been seen, he had absolutely nothing to be embarrassed about. In fact, to the contrary. It had taken a good deal of probing on my part to get him to loosen up on the subject, and then a good deal of further reassurance to get him to allow for its inclusion in a subsequent public conversation between the two of us at the opening of a big new show of his at his LA dealer Luis de Jesus’s spanking new space, and then for its inclusion as well of course in the Morris Museum catalog essay which formed the basis for this current series in the Cabinet. But in the end, I think he was relieved and even grateful to have finally loosened the grip of that knotted resistance, and indeed, a few months after we’d concluded our work together, Federico called and indicated he wanted to drop by, there was something he wanted to give me.

And now it was my turn to be thoroughly abashed. For he proceeded to carefully unwrap a large rectangular package, and there inside was, well,

this uncanny portrait (soft pastels, white pen and ink, gouache on wood panel, 24 by 60 inches) of me. The Writer Dissects the Artist, Federico told me he had titled the thing, and he went on to explain how he had based it on El Greco’s 1571 portrait of Guilio Clovio, an eminent book illuminator who Vasari had called “the Michelangelo of the miniature,” and who had in turn helped the Greek artist settle in Rome. Just as El Greco had shown Clovio holding one of his books with, in the background, a stormy landscape more suggestive of El Greco’s own concerns, so Solmi had cast me pointing to one of my texts (presumably this very one you are reading) with, in the background, an image more immediately suggestive of one of his own roiling passions. At any rate, the piece now holds pride of place in our dining room,

where my fractalized finger can be seen to be pointing at the 1830s portrait of my grandmother Lilly Toch’s Viennese great-grandfather.

Several weeks later, Federico called me with a story. A few days before, out of the blue, he’d received a phone call from someone at the University of Bologna informing him of their desire that he join them and other distinguished graduates of the University’s arts program for a weekend-long celebration of the institution’s continuing role in the cultural life of the city. Blushing at the recognition, Federico had to inform the lady that, actually, alas, he never had in fact attended the University, making it her turn to blush, offer profuse apologies, and then sign off in embarrassment. A few hours later, however, Federico went on to tell me, the lady called back to say that notwithstanding that fact, the Art Department wanted to invite him to return to Bologna for a separate celebration in their precincts, since he was nonetheless a proud son and worldwide cultural representative of the entire city. Whereupon he accepted the invitation, as he now told me, on condition that they invite me as well to conduct any public conversation.

Which was indeed odd, since I don’t speak Italian, but he said not to worry, we’d figure that out, and which is how, a few weeks later, I found myself in Bologna, traipsing about by Federico’s side, as he repeatedly got interviewed by the local press (in one case, I was myself included in the photo that ended up on the lead arts page of the evening daily—funny town, I found myself thinking, all you have to do is show up and you end up in the paper)

and toured about his old haunts: the palazzo studio with frescoed ceilings and painting mezzanine that had been his last apartment in town before he set out for New York over twenty years ago; the building that he’d grown up in with right up there the window of the narrow room he’d shared with his brother; the framer’s shop across the street where he used to hang out as a child (the framer in question was still there, carving ornate Renaissance style wooden mountings, and the two compared notes);

and then the teeming market where he and his brother had had their shops (various merchants poured out of their booths to greet and reminisce and fawn over him), and then the butcher’s shop itself, still manned by the same fellow to whom they had sold it over twenty years ago.

The two of them caught up with each other (on the way out, Federico expressed a purist veteran’s professional dismay at the way that such shops nowadays felt the need to supplement their offerings with extraneous jars of condiments –“Mustard!” he could barely get over the sacrilegious intrusions).

We went out dining (the food!) with his old boulevardier mentor Cherri, and touring the town with his brother Allesandro, who it turns out had also himself given up the butcher’s trade not long after Federico left for New York, transforming himself into a contractor-developer, and a highly successful one at that: he showed us an apartment tower that he had recently completed and it turned out that, under the influence of his younger brother’s example, he’d become something of an arts patron himself, commissioning colorful murals from noted local artists to adorn the flanks of his developments).

At length, the afternoon of our panel gig at the university arrived and we were given the big lecture hall, a baroque onetime Jesuit side-chapel with a high vaulted ceiling, rimmed with marble statues and plaster-cast Greek and Roman study copies. The room was packed with old friends and young students and a sizeable smattering of curious locals drawn by all the newspaper publicity. My longtime friend and occasional co-conspirator, Canadian museum man James Bradburne, had come down from his current perch directing the prestigious Brera picture gallery in Milan (“the Louvre of Lombardy”) to serve as translator, and the audience sat rapt as Federico for his own part grew quite emotional as, under my gentle prodding, I had him rehearsing his butcher roots. We projected passages from his videos onto a large screen behind us. Across the ensuing Q & A, the students seemed particularly interested in his virtual-reality experiments and, naturally, the mysterious success of his various NFT projects. Bradburne, for his part, was especially taken with the volumes into which Federico had compiled all the various skins of his respective digital characters and on the spot committed himself to an exhibition of same in the Brera’s neighboring Biblioteca sometime during the coming year. It was quite a day.

The following morning, just before I had to be leaving, Federico took me over to the great St Peter’s Basilica in the town’s center, there was something he wanted to show me. And there, in a chapel off to the side, towered Giovanni da Modena’s vast fresco depicting Dante's Inferno. As we stood there, veritably gawping at the thing, Federico related how as a boy he’d used to sneak into the building to gaze transfixed upon the monstrous vision, and it went without saying that here, too, we were being vouched a further vantage upon the buried taproots of his entire career.

* * *

Speaking of the Devil (A political bagatelle)

In just a few weeks (the weekend of October 13-15), a New York City municipal golf course will be playing host to the latest installment of the Saudi-backed Aramco Women’s Golf tour (a close cousin of the more controversial men’s LIV golf-cleansing insurgency)—though not just any municipal golf course nor in just any part of the city. This is all going to be transpiring at the Ferry Point Golf Course in the Bronx (the poorest borough in the city in one of the poorest zip codes in the nation), a course administered since 2015 by the notorious Trump Organization and universally known by the blaring insignia the organization plastered across a long berm visible (indeed virtually compulsory viewing) to all traffic coursing down the Bronx-facing side of the Whitestone bridge, as TRUMP LINKS.

That the Trump organization, with its long history of racial housing bias, was granted this particular concession in a borough 44 percent of whose population was black raised all sorts of eyebrows at the time, but no one was particularly surprised when the new administrators of this public amenity raised its day rates to $180, more than three times that of any other publicly owned golf facility in the city (that was all just par for the course). Nor should anyone be particularly surprised that the Trump Organization would pander to Saudi interests with this latest collaboration (this being the family whose son-in-law Jared Kushner had recently had his nascent hedge fund lavished with a $2 billion dollar investment from the Saudi Sovereign Wealth Fund, under direct orders from the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, presumably in compensation for services earlier rendered).

But the whole thing still rankles, just as that damn banner sign has been rankling me for years now, every time I found myself venturing down the Bronx side of the bridge, bound for my home a few miles further on in southern Westchester. And the banner, anyway, would have been so easy to fix by way of the tiniest of alterations, a scheme I kept urging on the politically minded youth of my town, alas to no avail (not yet, anyway). All that would be necessary would be the midnight application (by way of paint or chalk) of two further complementary perpendicular lines to the L in the banner (my friend Gerri Davis even came up with a video snippet illustrating the scheme) and the true nature of the entire enterprise would become visible to all.

A prospect, at any rate, all the more appealing this coming month, what with the way Trump Links so thoroughly reeks of Saudi Pork.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

A consideration and celebration of a luminous series of vertiginously mysterious new photographs by the New Mexico mid-career master Kate Joyce (buckle your seat belts); and more…

Appreciate the weight you lean on Solmi's earlier trade. This is no longer the country you can disappear in how it was I felt, still in 1993 when i left high school. All the analogies between the digital skins and butchery are speculative. But that is the kind of thought experiment we like. Differently than being indifferent, you wish for Frederico to stay productive and propose that he is carrying over ideas from his embodied last life. Seems true too because he comes from work in an excess of vitals, and he chooses to parody excess.