October 28, 2021 : Issue #2

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

HEY, WELCOME BACK!

We’re building this ship as we sail it (check out the great Kay Ryan’s marvelous short poem on that very theme here), so we hope you’ll bear with us. For more on the general ambitions behind this whole fortnightly venture, check out the introductory note to the inaugural issue from two weeks back, here. And as far as this issue goes, as you will see, we are featuring the first part of an extended profile of Jack Brogan, the wizardly nonagenarian fabricator behind much of Southern California’s Light and Space art movement; another shaggy dog of a FOOTNOTE, this one about penis bones; a bovine Derrida-Nabokov CONVERGENCE; and in the A-V ROOM, a conversation with disability activist and artist-memoirist Riva Lehrer. So dig in, enjoy, and subscribe to future issues simply by supplying your email address at the link at the bottom of this issue: you’ll get a fresh new number delivered straight to your emailbox every second Thursday, and all for free (at least for the extended time being, anyway). And do please pass word of the whole expedition along to your friends and colleagues! All are welcome.

This Issue’s Main Event:

THE ALCHEMIST : A Profile of Jack Brogan

PART ONE OF TWO

“If we were in Japan, he would be a national treasure.”

As Margaret Honda, who was in the process of writing a master’s dissertation about his practice, parsed things back in the summer of 1990, as part of a three-way conversation in Visions magazine, “One thing a lot of artists know is that if you try to get something done in a regular industrial shop, they often restrict the work to what they normally handle in order to make a profit. The people who have the equipment to do what artists want don’t have the time or the interest, and the people who do have the time and interest often don’t have the resources.” Regarding which he himself concurred, sheepishly, aw-shucksingly, as is his wont, observing how “We don’t worry too much about the business part.” At which point, the artist Lynda Benglis intervened: “Well, it’s not only that. He doesn’t just deal with the materials, he deals with the aesthetics and the feeling of the piece, and that’s much more important than just having a fabricator.”

“Everybody was using him back then,” the artist Doug Wheeler recently told me, when I called to ask him about the fellow’s role in the gestation of the Light and Space movement, the Finish Fetish-flecked “Cool School” of Southern California art, as it got variously characterized back then in the mid-’60s and ’70s “It would have been hard to imagine the scene without him, or for that matter what it is going to be like up ahead when he’s gone.”

I was collecting impressions because the news had started circulating that, now approaching age 90, the guy was getting set to retire—as Wheeler suggested, an almost inconceivable prospect.

“He’s the godfather of a whole field,” Christopher Knight, the premier art critic at the Los Angeles Times, opined for an online commemoration of the freighted moment over on the Art Report Today website. “Today … fabricators are a dime a dozen, but he is one in a million.”

Ed Moses, one of the seminal artists associated with the Ferus Gallery core of the movement from its earliest days, used to refer to him as “The Wizard,” keying off his stunningly various competencies, and Christopher Pate, a more recent artist and exhibition manager, seemed to concur, as part of that same Art Report Today symposium, denominating him Gandalf, in part owing to his taste for alchemical secrecy. Albeit a Cowboy Gandalf, his signature penchant being “for high end cowboy boots made of exotic leathers such as alligator and snake …any pair of which can cost as much as a decent used car,” which “for a man not ostentatious in any other prominent way” struck Pate as “an admirable gesture.”

“Somebody once described him as a sophisticated hillbilly,” Helen Pashgian, another of his earliest artist clients, told me. “As far as I am concerned, he is one of the most generous people ever to walk the planet.”

“A consummate Southern gentleman,” concurred the artist John Eden in that Art Report Today digest, going on to recall the time “in 1976 when he was in Amsterdam working on a James Turrell install. After the opening at the Stedelijk Museum, a selected group of insiders ended up at a canal-side outdoor café, during dinner he couldn’t help noticing how a notoriously misbehaving German gallerist was being abusive toward the assistant curator’s wife. After having been asked several times to knock-it-off, the dealer stepped it up a notch by pouring his glass full of wine into the woman’s purse. For our consummate gentleman, that was a bridge too far, so he picked the gallerist up by his finely tailored britches and cast him into the canal, just ‘to cool him down some.’”

Elsewhere, in a Bill Clarkson documentary chronicling the manifold technical processes of the same gent, Eden had summed things up, “If we were in Japan, he would be a national treasure.” In the Art Report Today festschrift, though, Eden’s characterization had been a tad more sulphurous. After celebrating the way that working with him could afford artists “a perfect union of their original intent, intertwined with his encyclopedic input of materials,” Eden went on to say, “Hanging out at [his] shop back in the day was like being at Robert Johnson’s Crossroads. In short, it was the nitty-gritty real epicenter of the West Coast artworld, where everybody came to make lightning strike.”

The veteran artist Peter Alexander, another of the fellow’s earliest beneficiaries, went the opposite direction. When I asked him a while back how he would characterize the guy if he were, say, trying to frame his role for the benefit of someone at a dinner party who’d never heard of him, he paused for a moment and then responded, “He was The Angel. He set the standard.” Was it that he only chose to work with artists of that certain standard, I asked Alexander, or was it rather that all of you felt you had to stretch yourselves even to be worthy of his ministrations? At which point Alexander doubled back, “Well, I mean, I said he was The Angel. He wasn’t God!”

“A living folk hero” is how Honda put it at another point. The Ferus veteran Larry Bell, for his part, zeroed in on the guy’s hands: “They’re unique: those long fingers. How the way he holds even the most delicate things is the opposite of dainty: just matter of fact. He comes off as shy, but believe me, he is not afraid to tackle anything. Behind that hesitant veneer, he has prodigious self-confidence.” Guy Dill, meanwhile, keyed off on his ears, citing his obvious mastery as a technician and an engineer, but more especially his exquisite capaciousness as “a listener.”

He’s been running his “own one-man think tank” is how Eric Johnson, one of the leading second generation Light and Space sculptors, put it, “He went about it as a real chemistry solution. You know, this is the components, this is the solvents, this is what the binders are, and he worked that way towards it, which nobody really did, you know in the past. Artists don’t really care about all that stuff, we just care if it works or not. But he would know why it worked.”

Sometimes he characterized himself as “a technical artist,” by which he meant that for him it was never just a job, as it usually would be for any ordinary industrial fabricator; he demanded total involvement in each fresh project (and he rewarded such engagement). “Some people can’t accept the fact that I’m actually involved in their work,” he told Honda at one point. “But then we don’t work together very long.”

For Robert Irwin, the artist who’s known him the longest, who likes to think he “discovered” him and then began turning all the other artists onto his discovery (the two are almost the same age, and for all its complications, theirs is still probably the closest of his artistic relationships)—anyway, for Bob, it’s really quite simple. As he told me the other day, “He was simply integral to the whole scene. He became The Man, and to this day he is The Man.”

*

As a boy growing up in Depression era Tennessee, living with his older sister and brother on his grandparents’ farmstead 25 miles northwest of Knoxville, little Jack Brogan started coming by his trove of practical knowledge from the very outset.

Actually his sister Beatrice wasn’t his sister: she was his mother. When she’d been a teenager, fresh out of high school, a few years earlier, she’d fallen hard for a drinking buddy of her brother Elmer’s, an engineer named Horace Seidner who was passing through the area, laying down the Chicago-Atlanta Highway, and he quickly proceeded to spirit her back to his own hometown of Springfield, Ohio, where Jack was born in 1930. But Seidner soon grew bored with the both of them, going out carousing and coming home mad, and a year later Jack’s grandfather William Brogan came up to Springfield to spirit mother and son back to the farm, adopting the boy soon after and fending off various attempts by Seidner over the ensuing years to kidnap him back. It wasn’t until Jack was five or so that he began to sort out just who was who.

Grandpa William Brogan was a prodigiously industrious fellow. By day he worked as foreman for the railroad, two of whose lines coursed along either side of the farm’s perimeter. As a result of its position, slotted like that between the two lines, the farm wasn’t hooked into the surrounding electrical grid till well into the Tennessee Valley Authority ’30s; but in the meantime, William had contrived an elaborate system of Coleman gas stoves, lanterns, and pipe connections, all of which fascinated young Jack. The old man had a blacksmith shop, into whose service as bellows-minder Jack was conscripted from virtual toddlerhood. He had a garage with a drop floor, and two separate water systems, and his grandson regularly traipsed about behind him as he worked on both. In plusher times Grandpa had bought up five surrounding farms which he rented out, so there were all those repairs as well, with Jack regularly in tow. Jack’s grandma, Susan Jane, a sort of herbal healer and midwife, kept a fruit tree orchard and a smokehouse, the latter two of which likewise absorbed the boy’s attention.

Jack was an exceptionally inquisitive and restless rascal from the start, and regularly found himself getting subjected to swift applications of the switch by his exasperated grandfather. During one of the sessions we had several months back at the kitchen table of the Santa Monica home Jack shares with his wife, the abstract painter Edith Baumann, he recalled how at age four he’d taken apart a clock—he was always taking things apart and trying to put them back together, only this time he couldn’t figure out the last steps, and for fear of the switch, he just took off, running away and not resurfacing till well after dark. (He’d often well up in tears, his voice halting, as he dredged up such memories.) A few years later, when little Jack had contrived a small lab for himself in the basement, he was trying to concoct ink for a quill pen he’d fashioned, and one of his cousins ratted on him to Grandpa, said he’d stolen some of the grandfather’s ink, and his Grandpa came storming down accusing him of the theft, and Jack protested that, no, this was his own formulation, and Grandpa roared “Don’t you lie to me!” and tore into him with the switch, cutting his back up good—but where was your mother, I interrupted, couldn’t she protect you? “Aw,” Jack said, “she’d re-married and she was long gone. My grandma was less severe,” he added, as an afterthought, “and sometimes she intervened, but she died by the time I was eight.”

Helen Pashgian recalled for me how once, early on in their working relationship, when Jack was being exceedingly exacting in his demands with regard to her own polishing efforts, she’d asked him how he himself had come by such intense discipline, and he told her a story about how “when he was very young, he noticed how his Grandpa kept a jug of some sort of hooch up on a high shelf from which he took a swig each evening, and naturally the little boy asked to try some and was told, ‘No, that’s not for you.’ But over the next several days the kid began trying to figure out how to get at the jug, piling chair upon box upon chair and getting closer and closer, and his Grandpa must have been noticing this, because when he, Jack, finally reached the jug and brought it down and took a swig for himself, it turned out his Grandpa had replaced the hooch with gasoline or linseed oil or some such, and the little boy swallowed a whole mouthful, to memorably burning and gagging effect. And he told me,” Pashgian continued, “how he’d taken two big lessons from the experience. One, never again to contradict his Grandpa. And two, most importantly—and he pointed to my own inadequate polishing efforts in this regard—how some things are just absolute.”

Grandpa was an anti-FDR Republican, Brogan recalled, though he donated the land for the local school, which Jack attended, doing well enough in math and science and, to some degree, history, but proving completely hopeless at English and reading. The only A he ever got was in chemistry, which he loved. By age nine he had taken on an after-school job working for a Dutch architect who’d launched a nearby practice, helping with cabinet making and finishing (he used to love sanding—both rendering the sandpaper itself out of silica and horsehide glue and then sanding and resanding the various objects, losing himself in daydreams); and presently, after age 12 (by which time he’d begun sprouting the tall and lanky body by which he’s so well known to this day), he was also driving the architect around, especially after the latter’s visits to the local honky-tonk speak-easy. His grandfather died when he was 14, after which he lived for a few years with his uncle, who’d take him fishing and employed him in his concrete-block-and-pipe making factory. Starting at 16, he began selling Bibles, at which he proved exceptionally proficient, earning upwards of 30 to 50 dollars a day up and down the backroads leading back to Knoxville. (“It was a bit of con,” he confesses, “since I was a nonbeliever, but I was trying to save up for college.”)

On the very day he graduated high school, he high-tailed it to Detroit, quickly snagging jobs building engines at Chrysler by day and car bodies at General Motors by night, and enrolling in the latter’s four-year Tool and Dye Making Course, of which he only completed six months when a series of post-war strikes swept through the auto industry, and he returned to Tennessee, where he enrolled in a local college, studying engineering, but only lasting another six months. (“I just couldn’t deal with the literature requirements,” he explains.) That would prove the extent of his formal post-secondary education: everything else he’d continue picking up as if by osmosis—his being an exceptionally porous sensibility. (“Everything Jack knows,” Robert Irwin once told me, approvingly, “he knows by experience and not from books.”) He got odd-jobs trucking produce from farms to road stands and even ran a general store of his own for a few months, by which point the local draft board caught up with him.

It was 1950 and he was sent down to Alabama to train for a pontoon bridge building company and up to Wisconsin to train others at same, and then out to Korea, where he served as a scout and sharpshooter in the 24th infantry for 27 harrowing months, an experience about which he tends to grow even more laconic than usual, not hazarding much more than that he’d “faced terrifying life-threatening experiences every day and seen things I’d rather not go into.” Had he ever been injured himself? “No,” he replies, pausing: “I paid attention.” End of that part of the conversation.

After his release from the army in 1953, he returned to Tennessee, where he took to buying, repairing and reselling used cars; running moonshine through mountain passes; and working for his uncle, hauling concrete blocks to Oak Ridge, on the southeast side of Knoxville, where the Atomic Energy Commission was quickly expanding operations. He presently obtained clearance to be able to work in the controlled part of the lab there, initially on the night shift familiarizing himself with precision instruments, checking uranium for purity and waste as it was leaving, and presently getting introduced to all sorts of other cutting-edge innovations in acrylics and plastics.

Concurrently, he bought himself a concrete plant for which he innovated a system whereby he could pour blocks in the morning, steam cure them over noon, and load them for delivery by five, while also casting custom architectural parts and inventing a separate system for extruding concrete pipes.

At which point, in late 1957, what three years’ worth of North Korean and Chinese soldiers couldn’t accomplish, a drunk driver speeding at 80 miles an hour managed to do in a split second: laying him low with an excruciating spinal injury. Following experimental neck surgery (“the first surgeon to do it”) and an extended period of convalescence, Brogan’s doctors recommended he head out west, to Arizona, where the warmer and drier climate might facilitate his further recovery. He spent a couple weeks in Phoenix, grew bored, and headed on to Los Angeles.

*

Los Angeles, on the other hand, especially in the booming late ’50s, was a whole other kettle of wax. And resin, and polyurethane, and acrylics—and aerospace and tract-housing and high-end design. And Brogan threw himself into the roiling mix with avid enthusiasm.

He started out with a little cabinet and furniture-finishing shop of his own on Melrose, with a sideline in adult games (X-rated games!? “Oh no,” he clarifies, “inlaid tabletop board games and the like for grown-ups, which were very popular in those days before laptops and cable TV”)—until one night that studio burned to the ground. And then he worked for Packard Bell for a while, before launching a further succession of studios, working his way west toward ocean-fronting Venice where he’d be based by the mid-’60s. He’d arrived in town with a wife (a high school sweetheart from back in Tennessee), and they soon had two daughters, so he was regularly working two full time gigs at the same time. He designed lobbies, fabricated models, and provided logos and other increasingly elaborate sorts of signage for tract developers like Dunn Realty and Eli Broad. (“I was always offering something extra—gold leaf, or a particularly exquisite finish—to give myself an edge. I was concocting special recipes for the various urethanes, and by the time others caught up, I’d simply have moved on.”) He innovated manufacturing processes for Knoll Furniture and solved production problems on Eames designs for Herman Miller. He did emergency overnight jobs for Hollywood clients (the directors loved him). He always had at least one vintage model automobile in the back that he was working on (and does to this day). He was in his element, and beginning to make a solid living.

Before that first studio burnt down, he’d sometimes take his lunches over at the Lucky U, a local pool hall known for its Mexican plates, where a bunch of young artists—Robert Irwin, Billy Al Benston, Craig Kauffman and others from the Ferus gang—seemed regularly to gather and banter. So was that where he first met them? “Actually, no,” Brogan explains, “I’d just watch them from a distance, they were pretty noisy and outrageous, and I’d be thinking, ‘Don’t those guys ever work?’” Why didn’t he join in on the festivities? “Oh, I was pretty shy, and anyway, I didn’t want to waste my time, I had work to do, I had mouths to feed.”

But as it happens, Irwin himself walked into Brogan’s cabinetry shop one day a few months later; he’d tried everywhere but he was still looking for someone who could help him in crafting a gently compound-curved, convex-bowed armature over which he was intending to spread canvas for a series of dot paintings he was about to undertake. “And as I say,” Irwin for his own part recalls, “it became immediately apparent that this guy was The Man.”

“I suggested he do the armature for those canvasses the way they used to do the old biplanes,” Brogan recalls.

How had he known about how they used to do the old biplanes? “Oh, once, when I was about six, my Grandpa took me along with him to some sort of political meeting, and I got bored and began walking around and came upon this guy out back who was building himself a barnstorming plane, cutting out the thin wood struts for the wings, and I was just mesmerized, spent hours watching—they had to come find me.” And he remembered that technique from all the way back when he was six? “Yup,” he nodded. (Edith on the other side of the kitchen table just rolled her eyes and smiled at me, as if to indicate how, Yup, this was typical, this is what we’re dealing with here.)

Brogan’s talents were evident to all sorts of folks besides Irwin and he was regularly getting lucrative offers to join high end design and cabinetry firms, as he regularly would for decades to come, but, dreading “being owned by or beholden to others,” he always demurred. Instead, in 1965, he founded Design Concepts on Lincoln Boulevard in Venice, which offered “fabrication on a custom basis for builders, architects and industrial designers.” Unlike most of his competitors, when Brogan took on a job, say, executing a luxury desk, he would finish and polish and buff the thing all the way around, including the base and the undercarriage, and the interiors of the drawer sleeves, places that no one would ever bother to look, because, as he would say, “How could one not?” Such all-around perfection was simply integral to the integrity of the work. (Shades, again, of his Grandpa.) During the firm’s early years, 30 percent of his business came from NASA and the Southland’s defense and aerospace contractors (these were the peak years of both the space race and the cold war) and involved the most advanced innovations in resin, laminates, plastics, and other such materials applications, and all the while Brogan was forging compounding innovations of his own and steadily equipping his studio with the capacity for executing them.

Around the same time, Irwin came back to Brogan as he was trying to figure out how to produce the ever-so-slightly bulging circular discs he was intending to float out from the wall in his next (and last) series of paintings. (The automotive body shops he’d been auditioning were having trouble exacting the precise swell of the thing.) “Before Jack,” Irwin told me, “I used to have to drive all over town looking for folks who could try, and usually fail, to achieve the effects I was after. But Jack could do it all, or at any rate would know who to call on for anything he didn’t already know. It was like one-stop shopping.” And more than that: it was becoming a non-stop symposium. Irwin was spending more and more of his time over at Brogan’s (Design Concepts was less than a mile from Irwin’s own Venice studio), riffing and blue-skying, and increasingly, for all intents and purposes, collaborating.

“The issue with those discs, especially the later acrylic ones,” Brogan recalls, “was how to give them enough tensile strength so that they didn’t sag: they were extremely delicate.” Irwin, for his part, had gotten to a point in his career where he was less and less interested in the object as such (couldn’t even be bothered to make it himself)—or rather, to be more precise, he was becoming more and more interested in the object as an occasion, a prompt, for the experience of perception, which was his increasingly consuming focus. “And the thing about that kind of work, when the artwork is merely the cue and not itself the subject matter,” Irwin continued, “is that the object has to be expertly, meticulously crafted, precisely so as to avoid calling attention to itself, and in that regard, there was just nobody but Jack who could do it.”…

Next week: PART TWO

* * *

A-V ROOM

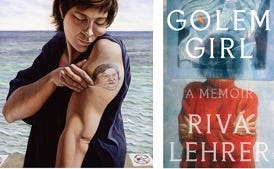

IN CONVERSATION WITH ARTIST AND DISABILITY ACTIVIST RIVA LEHRER

Continuing on with a survey of the recent series of Zoom conversations I curated under the auspices of Arts, Letters and Numbers and the Italian Pavilion at this year’s 17th Venice Architectural Biennale, this time out I engage Chicago-based artist and activist Riva Lehrer.

That Ms. Lehrer is alive at all is a matter of remarkable luck and happenstance. Had it not been for the fact that in 1958, her mother was working as a researcher in a lab doing groundbreaking work on natal anomalies, Riva, presenting with an acute case of spina bifida, might not have long survived her birth. But she benefited from both innovative surgeries—and the visionary attentions of that mother. Now, decades later, Ms. Lehrer has become a leading figure in Disability Culture in the United States, known internationally as a portrait artist whose work challenges staid conceptions of beauty through images that depict the power and allure of variant bodies—and lives.

On this occasion (as it happens, the 46th anniversary of the death of that mother), my conversation with Lehrer drew on the latter’s extraordinary recently published memoir Golem Girl to anatomize the space—physical, mental, and architectural—of disability, interdependence, resiliency, and hard-won independence.

View our conversation here.

* * *

Later this year, the worldwide paper shortage permitting, I will be publishing a new book, regarding which, further details anon. In the meantime, there’s this:

FOOTNOTES FROM A FORTHCOMING BOOK YOU DON’T HAVE TO HAVE READ, OR EVER READ

Footnote #5

Compare Zohar’s conception with the more recent artist Charles Bragg’s inspired etching “The Sixth Day.”

“God invented Man,” in that transcendent formulation variously ascribed over the years to Mark Twain, Voltaire, Frank Wedekind, and countless others, “and Man returned the favor.”

As for Eve, lounging there and still only half-formed on the Great Puppeteer’s worktable in Bragg’s conception, that of course is a whole other story. But one that has long been misconstrued, or so argue a daisy chain of recent contemporary biologists (a doff of the cap to Walter Murch for alerting me to this particular trill). As Richard O. Prum, Yale professor of Ornithology and Head Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at the Yale/Peabody Museum, relates in his Evolution of Beauty (2017), the whole notion of God having fashioned Eve out of Adam’s rib has never made much sense (early on, kvetching Talmudists were pointing out that men and women still had the same number of ribs, so what was up with that?), and the reason it doesn’t is because He didn’t. It’s all been a huge misunderstanding.

(Trigger warning as to what follows: any dallying children are emphatically encouraged to revert immediately to the main text.)

Prum notes that human males are among the relatively few mammals, and the only ones among the primates, that somewhere along the way lost their baculum, their penis bone. At which point the Birdman of Yale defers to Swarthmore developmental biologist Scott Gilbert and UCLA Biblical scholar Ziony Zevit, and their strenuously ignored 2001 paper “Congenital Human Baculum Deficiency: The Generative Bone of Genesis 2:21-23,” in which they point out that the ancient Hebrew noun tzela, which ordinarily gets translated as “rib,” could just as easily be rendered as a whole series of words “used to indicate a structural support beam,” continuing, self-evidently, to note how “‘structural support beam’ is a very succinct description of the baculum.” There is something eminently more narratively satisfying (or, alternatively, distinctly unsettling, depending on one’s point of view) about God having plucked Adam of his baculum rather than his rib as the basis for his creation of Womankind. But to clinch their case, professors Gilbert and Zevit further note how

Genesis 2:21 contains another etiological detail: “The Lord God closed up the flesh.” This detail would explain the peculiar visible sign in the penis and scrotum of human males—the raphe. In the human penis and scrotum, the edges of the urogenital folds come together over the urogenital sinus (uretral groove) to form a seam, the raphe… The origin of this seam on the external genitalia is explained by the story of the closing of Adam’s flesh.

Which in turn, I suppose, bring us back, in Zoharian terms, to that wet collodion print of the prim young lady (dare we think of her as Eve?) knitting herself that condom.

* * *

A BOVINE DERRIDA-NABOKOV CONVERGENCE

So my friend Mike Daisey sends me this marvelous find off the internet:

Phil Gentry writes: "A professor of mine went to go hear Derrida speak once. The entire talk was about cows, everyone was flummoxed but listened carefully and took notes about...cows. There was a short break, and when Derrida came back, he was like, ‘I'm told it is pronounced “chaos.” ’ ”

Which I in turn show to my half-Polish linguist daughter Sara, who makes the immediate association to a passage in a book of Nabokov’s, to wit, this one:

Translators of Shade’s poem are bound to have trouble with the transformation, at one stroke, of “mountain” into “fountain”: it cannot be rendered in French or German, or Russian, or Zemblan; so the translator will have to put it into one of those footnotes that are the rogue’s galleries of words. However! There exists to my knowledge one absolutely extraordinary, unbelievably elegant case, where not only two, but three words are involved. The story itself is trivial enough (and probably apocryphal). A newspaper account of a Russian tsar’s coronation had, instead of korona (crown), the misprint vorona (crow), and when next day this was apologetically “corrected,” it got misprinted a second time as korova (cow). The artistic correlation between the crown-crow-cow series and the Russian korona-vorona-korova series is something that would have, I am sure, enraptured my poet. I have seen nothing like it on lexical playfields and the odds against the double coincidence defy computation.

Which my daughter in turn goes on to anatomize, as follows:

It's from a footnote in Nabokov's Pale Fire. The fun thing, as Nabokov notes, is that, by coincidence, the joke works almost equally well in Russian and English. Oddly enough though, in Polish (where the words are complete cognates with the Russian terms), the wordplay doesn't hold up nearly as well. This is because Polish uses fewer epinthetic vowels than Russian (Poles being a stronger, more virtuous people, of course).

Korona --> Vorona and Crown --> Crow each involve only one letter change/deletion. Whereas in Polish, Korona --> Wrona requires one deletion and one change, and therefore reads as a less believable slip-up.

Similarly, in the second misprint, in Russian, Korova (cow) falls just one letter away from the target (Korona); while in English, Cow falls just one letter (deletion) away from the previous mistake (Crow). So both feel like plausible typos from a rushed newspaper editor. In Polish, however, Krowa is two letter changes/deletions from both the target (Korona) and the preceding mistake (Wrona)-- and therefore no longer feels like a believable typo. So the joke falls apart, despite the fact that the actual Polish words are much more closely related to the Russian originals than the English ones are.

What can I say? The girl is almost as loosey-goosey-synapsed as her father. Poor thing: I wonder where she gets it and how she survives.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT WEEK

The conclusion of the Brogan profile; in the A-V Room, Ren’s conversation with photographer Ken Gonzales-Day on the historical reality and artistic representation of Lynchings; another footnote, this one regarding a plethora of klutzes; and a Guess-Who convergence…

It’s free! You’ll receive a new issue via email every other Thursday.