A MIRACLE, A UNIVERSE

Extended Treatment for a Three-Part Miniseries

On the morning of July 15th, 1985, I traipsed from my office at the New Yorker several blocks over to the boardroom of Random House’s publishing headquarters to attend a news conference, at which, as things developed, I proved to be the only journalist in attendance. Too bad—or alternatively, lucky me—for as it turned out, the story getting told by the sole speaker at the dais was nothing short of astounding. The presser had been called to publicize the release on that very day, and at that particular hour, of the American edition of a book called Torture in Brazil and simultaneously, back in Brazil, that of its Portuguese language counterpart, Brasil Nunca Mais.

Indeed, it was explained, the release of the American edition was in no small measure a way of protecting the publication of that same book in Brazil—or at any rate, an attempt to render that edition’s immediate suppression less likely because more futile, since what any longer would be the point? Not that certain very powerful Brazilian authorities mightn’t have sorely wished they could indeed banish any trace of the veritably explosive book’s sudden existence.

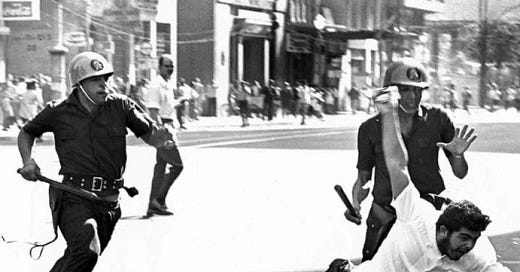

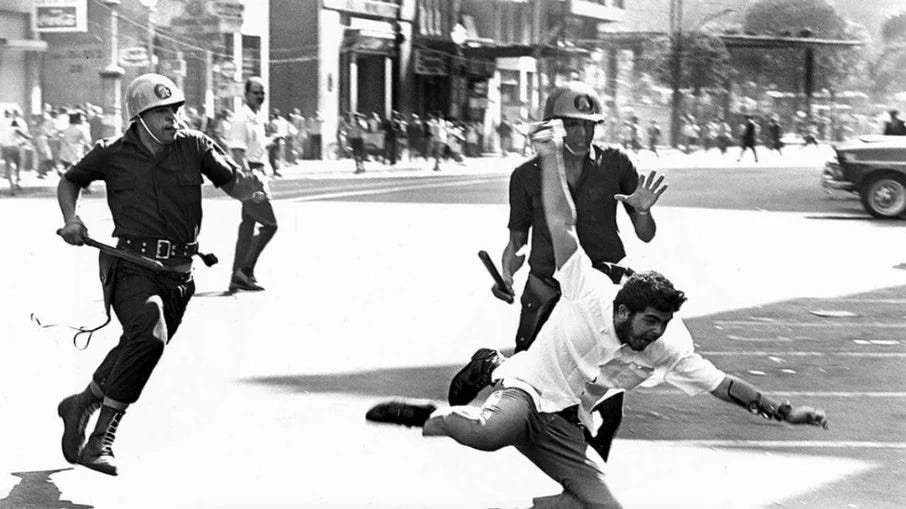

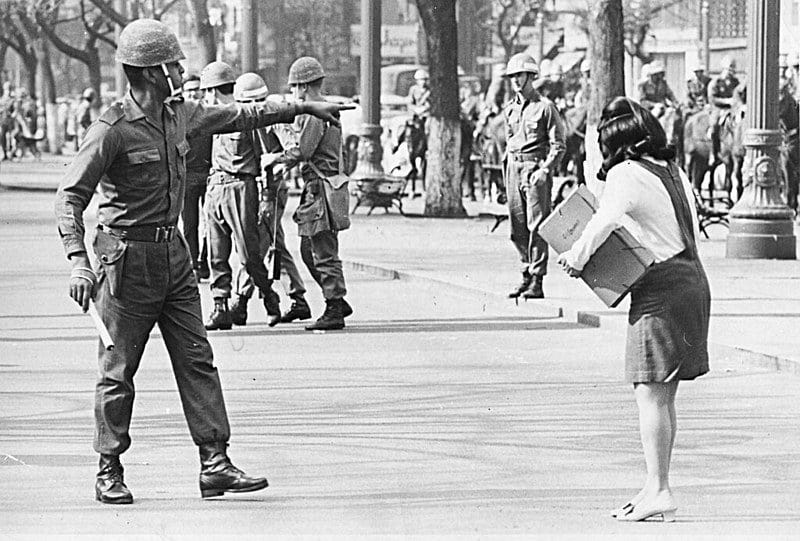

The speaker, Jaime Wright, the gruff stolid son of American missionaries and himself the then-current head of the Presbyterian Church USA in Brazil, explained how five years earlier, in 1980, Brazil’s military leaders, who’d been running the country ever since the American-backed coup d’etat in 1964 that overthrew the country’s duly elected social democratic president João Goulart, installing their own ever more brutal regime—the first of a series of such US-backed coups that was to install similar torture regimes in countries across the entirety of the Southern Cone of Latin America in the years that followed—at any rate, back then in 1980, at long last (and once again at the forefront of a tidal swell that would presently sweep across the continent), the Brazilian military announced that it would be launching an initiative known as l’Abertura, the Opening, and gradually cede authority to a tentative experimental civilian authority, but gently, ever so gradually, and still within strict bounds, in a process that would take five years (and indeed had only just culminated, a few weeks earlier, in the installation of just such a largely hamstrung, semi-freely elected civilian government).

The thing was, though, that back in 1980, the military—first things first—had lavished a permanent amnesty going forward upon itself and its allies regarding any acts of torture, disappearance or other sorts of extrajudicial suppression that might have taken place over the prior decades, while simultaneously insisting that no such activities had in any case ever taken place, and seriously implying that anyone who dared to claim otherwise across the years ahead could easily find themselves subject to arrest, torture, disappearance or the like. And it was at this point that a small group of former torture victims, in conversations amongst themselves, started to hatch a plan to get even with their torturers, albeit in a completely nonviolent manner—a terribly, indeed mortally dangerous, achingly long-term scheme based on burrowing into the regime’s own top secret archives so as to be able to spirit out documentation, in the regime’s own words, of its own prior depredations—a plot that was somehow now coming to fruition on that very day with the publication of this incontrovertible report entirely based, as I reiterate, on the prior regime’s own files. The report was being released utterly anonymously, with the exception of the public acknowledgment of its sponsorship under the auspices of Reverend Wright and his superiors at the World Council of Churches in Geneva, working in unprecedented ecumenical collaboration with Cardinal Paulo Evarista Arns of the Catholic archdiocese of Sao Paulo (who’d been conspiring the entire while unbeknownst to any of his superiors back at the Vatican or fellow church leaders across Latin America).

Little did we know on that July afternoon in 1985 that notwithstanding the fact that there hadn’t been any such news conference or news coverage back in Brazil, within two weeks and sheerly by word of mouth, the report would become the Number One Bestselling Work of Nonfiction in the country, a position it would retain for the next eighteen months, an unprecedented record (with the possible exception, as some wags pointed out, of the Holy Bible itself, though there was some argument as to whether the latter should be considered nonfiction). Still, I myself already had the good sense to realize that the story of how the report had come together could itself make for a great piece, and after Wright’s talk, I went up to him and asked whether, if I could make my way down to Brazil, he could put me in touch with some of those who had actually fomented and carried out the scheme—I wouldn’t need to know anyone’s names, just how in general terms they had done it—and Wright surmised that that should indeed be possible. I returned to the New Yorker offices, met with our editor William Shawn, who within two sentences approved the confidential project, and though it would still take me over a year wrapping up other projects, eventually I was off to Brazil…

…only to discover, upon arriving in Sao Paulo, that Wright wasn’t going to be able to put me in touch with any of the principals after all—none of them had yet broken their silence and nor were any of them willing to do so now with an American reporter of all things, they were all worried, in fairness not without cause, that I could be a CIA plant in cahoots with the military. Wright apologized, told me I could go on reporting on my own, that he would steer me right if I began losing my way, and in any case he suggested a number of publicly engaged experts and victims with whom I could discuss the years of the Dirty War in general. Which could well have been the end of my excellent scoop…

…except that, as it happened, I was traveling with my Polish wife Joanna (seven months pregnant with our daughter Sara), who back in the Solidarity days a few years earlier, even as she had been deeply involved in her own country’s insurgent union’s press agency, had occasionally freelanced on the side as an interpreter for visiting Spanish and Latin American reporters (just before Solidarity, she had graduated from the University of Warsaw with a Master’s in Latin American literature)—and the very evening of that dispiriting conversation with Wright, she and I went off to visit with one of those journalists who in the meantime had returned home to helm the entire foreign desk of the major Sao Paulo daily newspaper. The two of them had a great time catching up, and at one point he turned to me and asked what I was up to on this trip, and I began to tell him the whole sorry story about how I had been hoping to interview the people who had made the Brasil Nunca Mais project possible but that none of them would talk to me, they all thought I might be CIA, at which point he said that that was ridiculous, as it happened one of the key figures, the guy who actually composed the final report, had been a onetime roommate of his, and how, just a second, he’d go telephone him and assure him that I was alright, which he did. Whereupon the two of us, his friend and I, got together the very next morning, and that guy in turn presently vouched for me with a few others of his confederates, such that the day after that, when I got together with Jaime Wright once again, I was able to tell him that so far I had tracked down X and Y and Z and A and B—at which point, sputtering, he demanded to know, “Wait a second, are you in fact CIA!?”

Somehow we got past that crisis, I continued my reporting, returned home, and several months later, in May 1987, the New Yorker ran my two-part series, “A Miracle, A Universe,”

detailing the story of the whole adventure (those being the pieces, incidentally, that launched the curator Laurel Reuter in North Dakota onto her decade-long investigation of Latin American artistic responses to the Dirty Wars throughout the continent that culminated in the superb traveling show I touched upon a few weeks ago back in Issue 90A of this Cabinet, which is actually in turn what got me thinking about this whole background saga all over again.)

Anyway, during that period (now in 1987), the eminent producer David Putnam (of Chariots of Fire and The Mission fame) happened to be ensconced as the head of Columbia Pictures, and no sooner had the pieces run in The New Yorker than I got a call from his lieutenant Jack Lechner inquiring whether I and the various principals back in Brazil might be interested in seeing the story developed into a film: a veritable true-life human rights caper movie! Discussions along these lines proceeded apace until naturally, this being Hollywood, Putnam lost his job atop Columbia Pictures for entirely extraneous reasons and the whole thing came to nought.

I moved on, they moved on, Lechner in particular moved on to helm the feature film division of Channel Four television in England (where, among other things, he developed both A Crying Game and Four Weddings and a Funeral) before eventually getting lured back to New York to helm original feature film development at HBO. At which point, almost a decade on from our first contact, I got another call from Lechner asking me whether anything else ever came of those movie conversations, and since not, might I be interested in resurrecting the idea? HBO fronted me the money to go back down to Brazil to dig deeper into the story—in the meantime my book on settling accounts with torturers in Latin America, under the title A Miracle, A Universe (uniting the Brazil story with a parallel case study in Uruguay), had come out in the US and in translation in Brazil, and now pretty much all the principals in the original story were eager to talk to me, so I amassed all sorts of further details into the extended (way over-extended) treatment I now managed to turn in to HBO. Lechner and I spent several months trying to wrestle the over-long treatment into a more manageable basis for a movie, and were thinking about who to approach to develop an actual screenplay (I myself being pretty hopeless at dialog), when, Hollywood being Hollywood (and since I come from LA I’m never surprised when this sort of thing happens), Lechner got another job somewhere else and the whole project fell once more into abeyance.

Over the years, interest in the project (a sort of Missing meets Oceans Eleven) has flared up every so often, its pertinence alas everlasting, but so far nothing has yet come of it. More recently, it has seemed to me that, what with its surfeit of incident and wealth of intriguing characters, it might actually work better as a mini-series (say three ninety-minute segments) and a Brazilian-American coproduction at that (especially what with the American angle provided by Wright’s character and the family urgencies that had propelled him into the project in the first place, his own brother having been among those disappeared). As the neo-fascist Jair Bolsanaro came to power in Brazil, it seemed the story had taken on renewed urgency, and urgent interest was indeed expressed, but again nothing quite came of it. But now—and who would have thought it?—what with Trump’s depredations here in our own country, it once again seems to me that, alas, the story has become scarily pertinent all over again.

So anyway, with all that as backdrop, I thought that this might be a good time to publish my eighty-page film treatment here in the Cabinet, though cut into three segments across successive issues, along the lines of the three weekly installments the thing might merit if it ever were to become some streamer’s prestige mini-series.

And who knows, maybe somebody will know somebody and perhaps something will happen. In the meantime all of us can glory in the tale of a small band of onetime victims who indeed managed the miracle of hijacking the entire universe of documents secreted in their tormentor’s archives, and, at great personal risk, at length turned the tables and finally attained no mean measure of surcease. It seems to me that we all may need models of right conduct like that in the years ahead.

So, without further ado:

A MIRACLE, A UNIVERSE

(An extended treatment for a three-part miniseries)

(Note: I am referencing the original pre-Word, IBM Selectric hand-typed version, complete with occasional spelling errors and the like, so bear with me.)

For PART ONE click HERE.

PART TWO and THREE will follow across the weeks ahead.

"though there was some argument as to whether the latter should be considered nonfiction" great parenthetical

Lawrence,

I'd like to try with a couple of people.

One is my nephew who produces films for Netflix, lives in Venice Beach.

The other is a friend who moved to LA to do an MFA at UCLA in screenwriting (interned with Jodie Foster), is still writing screenplays. He had to work all the while as he wrote, has a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology, and held various positions in the administration of multiple Cal. State universities. He lives in Long Beach.

Let me know if I should get in touch with them.

This is a long overdue project that is at one of those peak moments.

Tom Forma (yep, Anthony Forma's cousin, but born 4 months after him in 1951)

963 Hulls Highway, Southport CT 06890

tomforma@gmail.com

cell: 860-881-1923