Following on, as one by one neighbors start disappearing

On second thought, maybe the first section of last week’s Cabinet, the one that started out anyway as a reminiscence of Janet Malcolm’s run of ever-compounding and complicating profiles (of Jeffrey Masson and subsequently Joe McGinniss et al) from back in the eighties, wasn’t as “Apropos of Nothing in Particular” as I let on in my lede, or at any rate let that lede lead me to assume. Because the evocation of my own reportorial impasse, there toward the end of the piece, at the way the Uruguayan junta chief General Hugo Medina somehow got me to laugh with him at his use of the euphemism “energetic” vis-a-vis the methods used to break down the victims of his own repressive regime’s disappearance apparatus is alas utterly of our moment, so much so that Nothing in Particular might be more so.

For hard as it still may be to believe, let alone process, in barely one hundred days we have already fallen into a form of governance in which legally resident individuals (currently by and large immigrants of one sort or another—mothers, fathers, students with entirely current green cards or asylum claims—but with every indication that such tactics will presently be getting extended to full-fledged citizens as well) are literally being spirited off the streets by masked men in unmarked cars and, without the slightest due process or the most tenuous access to any sort of recourse, whisked off to prisons, both at home and abroad, seemingly beyond the sanction of any sort of judicial oversight (the rulings of judges flagrantly ignored and the judges themselves now starting to get subjected to arbitrary arrest as well simply for even having expressed them), the legislative branch cowed into impotence by the abject servitude of its barely majority party, the executive branch a whipsaw of whims and tantrums, with no end in sight.

(Actually, full-fledged citizens are already beginning to get included in the expulsion round-ups, it’s just that they happen to be two and four and seven years old, the four-year-old with stage four cancer! My old colleague the jazz critic Stanley Crouch used to say that he’d learned everything he‘d ever needed to know on his kindergarten playground, which is to say that ten percent of the people are bullies, twenty percent are victims, and everybody else runs around squealing, “Not us, them!” Well, veteran schoolyard bullies Donald Trump and Steven Miller and their pals are still at it all these years later, only, in classic fashion, for starters, they’re still beating up on actual kindergartners! )

As Ezra Klein exclaimed a few weeks back in a vital piece of commentary, the emergency isn’t fast approaching, it is already Here, and it is Now.

Even the imagery of persecution conspicuously (intentionally) reeks of prior instantiations:

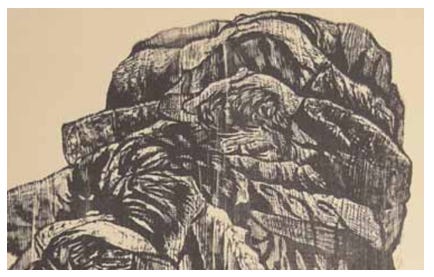

That last image in particular, the Uruguayan artist Antonio Frasconi’s depiction of a line of bedraggled political detainees getting filed into the country’s Libertad prison—for that was the name that the junta there had actually given their ghastly detention center: Liberty!—has long haunted me, and it is truly terrifying to see its like bubbling up once again in the context of our own political moment.

Not that the Uruguayan instance, as with all those Latin American Dirty Wars, was without its own distinct US contribution—see Constantin Costa Gavras’s film State of Siege for a rehearsal of the deep American insinuations into the roots of that particular catastrophe. In fact, in some ways, in much the same manner that the horrors of the first and second world wars in Europe were simply a case of Europeans starting to deploy tactics they’d already been visiting upon their colonial subjects for decades (aerial bombardments, poison gas attacks, concentration camps, systematic genocides and the like) but only now upon each other—so, many of the current Trumpian excesses simply constitute instances of our recent farflung neocolonial “national security” depredations getting translated back onto our own native soil.

As it happens, the first time I saw Frasconi’s etching was in North Dakota of all places. Not quite a decade after the New Yorker’s 1987 publication of my brace of reportages on the aftermath of the dirty wars in Brazil and Uruguay that would come to be gathered into my book A Miracle, A Universe: Settling Accounts with Torturers, I got a note from one Laurel Reuter, who introduced herself as the founding director of the North Dakota Museum of Art in Grand Forks, asking if I might be willing to come give the keynote address at the opening of their upcoming survey of Latin American artistic responses to the Dirty Wars. I admit to having been somewhat incredulous at the prospect (I mean, Grand Forks, North Dakota!?), but since I’m generally inclined to accept invitations to go places I haven’t been before, I accepted, and in the end I was utterly astounded by what I found there. Explaining to me that the North Dakota farmers who comprised some of her most devoted patrons were far more worldly and world-concerned than they were commonly given credit for being (she told me that many of them had three or four laptops lined up along the dashboards of their combines as they trundled about their fields, continuously monitoring changing conditions all over the world—they had to, such conditions having immediate implications for the sorts of things they needed to be planting and tending from day to day), she went on to explain how she herself had been blown away by the sorts of things described in my articles when they first ran in the New Yorker, and how she’d then taken it upon herself, every way-too-hot Dakota summer in the years since, to travel, on her own dime, down to one Central or Latin American country after the next, where, notwithstanding the fact that she didn’t speak Spanish, she would seek out artists who were contending with the legacies of those wars in their current practice.

And the show that had now resulted, spotlighting the efforts of fifteen such artists from all up and down the hemisphere, was a complete revelation. (Indeed, as became clear through my subsequent conversations with Reuter, the true genius of her curation hadn’t so much resided in what she included in her show as in what she left out, for she had seen work by dozens, hundreds of artists, almost all of it reflecting intensely heartfelt and worthy politics, but she had managed to limit herself to the fifteen most artistically compelling. And what a group, with what an overall impression!) It was easily the most powerfully affecting show I’d seen in years, and I quickly got on the phone and called Patrick Lannan, a deeply engaged arts philanthropist acquaintance from back in my LA days, and told him he really had to get up there right away to see it for himself. He did, and on the spot granted Reuter the funds to tour the show all through Latin America (to Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Brazil and Columbia, for starters). And everywhere it went the response was the same: what the hell was this gringa doing, having pulled together a show that we ourselves surely should have been assaying a long time ago? After that, Lannan funded a further tour of the show through US venues, and when it eventually washed up at the Museo del Barrio in New York City in 2007, the Times’s critic Holland Cotter concluded his rave review:

From Ms. Reuter’s stunning essay to the supplementary material, [the show] is a total-immersion emotional experience. And why is it that an on-the-road exhibition from a small museum in the Midwest is the most potent show of contemporary art, political or otherwise, in town? All I can say is that curators in our local museums should pay a visit, and ask themselves that question.

Ms Reuter went on to develop a whole slew of other similarly visionary and compelling shows in her little Midwest outpost (I remember in particular another pathbreaking one on Iranian women artists, a second on drones, and yet another on war and art in general) before retiring emeritus a few years back. (A Director’s Fund has been established in her name to help fund future such cutting-edge programming at the Museum she founded and loved into being—she was regularly being scouted for other much higher profile gigs elsewhere in the country, all of which she turned down—and I urge those of you who can afford to, to give it a thought and a nod.)

The catalog for “The Disappeared” show, as Cotter suggests, is a treasure, a dark affirming flame (you can also sample some of its pages here), and it is one of the singular honors of my life that Laurel asked me to adapt my keynote talk into its introduction, which I began with a poem by the remarkable Chilean exile poet Marjorie Agosin, long based at Wellesley (I was getting set to write her the other day to ask for permission to reuse it here, only to find out that she passed away, peacefully, in the company of her family, only a few months ago. Ah well, I am including it here anyhow in her honor; I hope and trust she would understand.)

Buenos Aires

by Marjorie Agosin

When she showed me her photograph,

she said,

this is my daughter,

she still hasn’t come home

She hasn’t come home in ten years.

But this is her photograph.

Isn’t it true that she’s very pretty?

She’s a philosophy student

and here she is when she was

fourteen years old

and she had her first communion

starched and sacred.

This is my daughter

she’s so pretty

I talk to her every day

she no longer comes home late, and this is why I reproach her

much less

but I love her so much

this is my daughter

every night I say goodbye to her

I kiss her

and it’s hard for me not to cry

even though I know that she will not come

home late

because as you know, she has not come

home for years

I love this photo very much

I look at it every day

it seems that only yesterday

she was a little feathered angel in my arms

and here she looks like a young lady,

a philosophy student

but, isn’t it true that she’s so pretty,

that she has an angel’s face

that it almost seems as if she were alive?

My own introduction goes on from there, and you can find it here, in a version reprinted at the time in The Believer, which also includes annotated imagery from the show and catalog, including the Frasconi.

As for that woodcut, what always gets to me, even when I am only revisioning it in my mind’s eye, is the ever-so-slightly upturned gaze of that one guy toward the back: its steady defiant lucidity, its insistent unstooped calling forth and calling out. For though the North Dakota show focused on acts of remembrance, it also keyed in on the ongoing presence of those who had been disappeared. Similarly, it calls out to those of us here in the present who are again witnessing the beginnings of such calamities right now, every day: and it’s not only our witness that needs to be called out (I am thinking of the ever-so-pertinent title of another recent book, this one on Palestine, Omar al Akkad’s One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This). So does our active engagement. This is all happening right now, and so do we all need to be.

* * *

See you next week!

A Comment from Prof. Juan E. Mendez:

Dear Ren,

What a wonderful entre in your Wondercab Mini! Just this week I participated in an online conference organized by WOLA and the National Security-Archives to draw lessons on forced disappearances and comparisons with the abduction of non-nationals considered deportable by executive fiat. It was attended by close to 500 persons and will be circulated soon, I believe.

Anyway, I loved your article and I am sharing it with my other panelists and organizers. Hope to see you soon.

Juan E. Mendez

Professor of Human Rights Law in Residence

(Former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture (2010-2016))

Washington College of Law

Lawrence, I’ve known Laurel most of my life - my father was the Dean of the College of Fine Arts at UND in the 70’s when Laurel was just starting the Museum. She blew my little mind back then with her shows at the Student Union and I’ve had the pleasure of continuing our friendship throughout the years, and being constantly entranced by the work she has chosen to show. The museum is poised to carry on this legacy of presenting challenging work - so important in times like these. Thank you for your tribute to Laurel and your contribution to this very important dialogue. As I tell my friends who feel overwhelmed by the dark turns we find ourselves cast into, Art Harder!! Warm regards, John Colle Rogers