WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

A glance back at the Janet Malcolm/3JMs affairs; and artist David Opdyke attempts to re-center climate chaos at the heart of our current discourse.

* * *

The Main Event

Apropos of Nothing in Particular

In conjunction with my preparations to leave for five weeks in Europe, in part to take on a gig at Berlin’s Humboldt University coaching recovering postdocs on how they might learn to write for and like human beings once again, I came upon a short obscure contribution of mine from a long while back that I thought some of you might find of passing interest, and what else in the end is the ’Stack for?

The backdrop for this particular piece was the Janet Malcolm/Jeffrey Masson scandal which consumed literati observers for nearly a decade back in the day, but for those of you who weren’t yet around or had better things to preoccupy yourselves with at the time, a quick refresher:

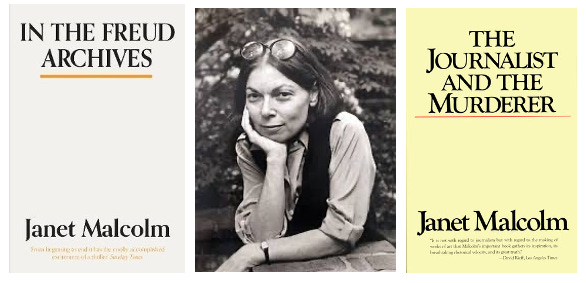

Janet Malcolm, one of the finest New Yorker writers ever, among the smartest, wittiest, slyest, most stylish and engaging and provocative, and for that matter one of the best purveyors and interrogators of the craft of narrative nonfiction, period—and a dear and vivid, albeit shy and sometimes self-effacing colleague—was one tough cookie.

Actually, the story quickly gets so convoluted that it could end up taking up the next several Substack issues, were I to even attempt to give it its remote due. The merest gist of things, though, is that in November 1983, Janet released a thoroughly engrossing, compellingly readable multipart account of a vast rumbling disturbance in the field of Freudworld across a series of New Yorkers entitled “Trouble in the Archives” (subsequently gathered in book form under the name In the Freud Archives, itself recently rereleased in a new edition by New York Review Books) which caused a huge ruckus all its own, not least because its main protagonist, a charismatic Sanskritist turned analyst-in-training turned Head-Honcho-protégé and presently Director of the prestigious Freud Archives turned renegade apostate named Jeffrey Masson, who’d related his life and his new misgivings over Freud’s deep betrayal of many of his early patients across dozens of hours of what he imagined to be thoroughly convivial conversation with Janet in the run-up to the article, pronounced himself thoroughly blindsided and betrayed by the piece as it appeared, insisting that he’d never even uttered any of the dozens of often quite self-damning remarks attributed to him, whereupon he sued both Janet and the New Yorker more generally for libel. Notwithstanding the fact that, in the event, the vast majority of those utterances showed up verbatim on Janet’s tapes and in their transcripts, in the end five of them did not (with Janet claiming that those had taken place during one off-tape interview for which she had unfortunately lost the notebook in question, though she retained her typed version of its contents), several judges allowed the defamation case to proceed on that basis, and it did—I kid you not—for the next ten years!

In the midst of all this, in March 1989, Janet unleashed a new and equally compelling narrative about an entirely separate recent journalistic train-wreck that occurred when the eminent reporter Joe McGinniss took it upon himself to reinvestigate the notorious case of an Army Special Forces doctor named Jeffrey MacDonald who’d been convicted of the exceptionally gruesome murders of his wife and two young daughters and sentenced to three consecutive life terms in prison, notwithstanding several pronounced irregularities at trial and the fact that the defendant continued to proclaim his innocence all the while. Even though McGinniss and MacDonald agreed to split the proceeds of the eventual book, which everyone expected to be a big bestseller, somewhere along the line McGuinness became convinced of MacDonald’s guilt after all (though he refrained from indicating as much as he continued to work alongside him), such that MacDonald felt deeply betrayed and utterly shocked by the book as it presently appeared. And he in turn decided to sue McGinniss. Which is where Malcolm took up the story, in thoroughly engrossing fashion, without at any point (this being one of the most uncanny aspects of her entire narrative) ever so much as touching on its likeness to her own still ongoing case. (For a more detailed account this whole cascade of imbroglios, see John Taylor’s famous New York magazine piece here.)

Malcolm had launched into her multi-part piece, entitled “The Journalist and the Murderer,” starting in the March 5, 1989 issue of The New Yorker, like this:

Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse. Like the credulous widow who wakes up one day to find the charming young man and all her savings gone, so the consenting subject of a piece of nonfiction writing learns—when the article or book appears—his hard lesson. Journalists justify their treachery in various ways according to their temperaments. The more pompous talk about freedom of speech and “the public’s right to know”; the least talented talk about Art; the seemliest murmur about earning a living.

Needless to say, this bracing pronunciamiento provoked a whole fresh kerfuffle all its own, with just about everyone weighing in on one side or the other or yet another side still. Within a few months, the Columbia Journalism Review took it upon itself to harvest a whole cropful of such responses, by way of a series of over twenty brief interviews conducted and collated by Martin Gottlieb (you can sample the entire collection here).

And as it happens I was one of those canvassed, and this (the piece I was referring to at the outset of this whole entry) is what Gottlieb has me down as saying (not that I contest it in the least, it’s just that, as I always do, when he took out his tape recorder, I told him I didn’t care what he used as long as he didn’t quote me verbatim):

You know about all the weird JM business in this story, with Janet Malcolm writing about Joe McGinniss writing about Jeffrey MacDonald and herself having written about Jeffrey Masson and the piece being called "The Journalist and the Murderer"? Well, I was telling someone you could have called the piece Les Jouissances Meurtrières—Deadly Pleasures or Murderous Orgasms—because the rhetorical tone of the piece is straight out of Les Liaisons Dangereuses.

It is out of the Age of Reason, when all kinds of people took perverse situations and derived from them immutable laws of human nature. Freud, of course, comes out of that tradition and Janet in turn gets a lot of her rhetorical tone from Freud.

The marquise in Les Liaisons Dangereuses has all these elaborate theories about the complicated power relationships involved in love and courtship, and she looks down on the ordinary people who think of love as something really quite simple. Janet's piece, in a way, is the sort of piece about journalism the marquise might have written.

The marquise's analysis is spellbinding. But in Les Liaisons Dangereuses it falls apart the minute real love enters the scene. Janet's thesis is spellbinding, too, and I want to emphasize that I think it's a remarkable piece of writing. But it falls apart in the same way. While the dynamic she describes is potential everywhere in journalism, it doesn't inevitably have to materialize. There are journalistic equivalents of love—compassion, engagement, conscience.

I am still on far more than speaking terms with all the people that I have done profiles of. And I think I have portrayed some fairly complicated individuals, and portrayed them as both admirable and also demonical and all sorts of other things. My ideal for a profile is that I want it to be as if you were meeting this person. The highest thing that I aspire to is fairness and transparency. Even when I do a profile of somebody I am critical of, I aspire to do it so fairly that he or she will say, "Yes, that's me."

I mean, I don't want to sound Pollyannaish. I'm all for doing devastating pieces, but I generally prefer to devastate institutions rather than people.

Now some people might feel that if you portray somebody transparently, you're betraying them. The marquise might feel that way, but I don't.

Let's say, for example, that I am describing someone who, as I get to know him, I realize is an alcoholic. I don't think I need to say the guy is an alcoholic. I can portray him in bars, talking about being thirsty, or do other things that will provide a kind of feeling about that, but not a label. Later on, if somebody says, "God, you know he is an alcoholic. You didn't say that," I can say, "Well, go back and read the piece. It’s there."

To label may in some cases be to betray. Whereas if you just show things, I think you can be fair.

By the way, sometimes in my political reporting I get into situations directly analogous to what Janet was talking about. In fact, there was one particular incident during my reporting recently in Uruguay when I dealt with these issues in the body of the text, but ironically the paragraph was taken out in part because the editors at The New Yorker did not want to call further attention to the Janet drama. My article ran only two weeks after hers.

I was interviewing General Hugo Medina, the former junta head who was now the defense minister. He said that sometimes when they were interrogating people during the military dictatorship, they would do so "energetically."

And I said, "Energetically?"

And the way I originally wrote it is as follows: "He was silent for a moment, his smile steady. For him, this was clearly a game of cat and mouse. His smile horrified me, but presently I realized I'd begun smiling back (it seemed clear the interview had reached a crisis: either I was going to smile back, showing that I was the sort of man who understood these things or the interview was going to be abruptly over). So I smiled, and now I was doubly horrified that I was smiling. I'm sure he realized this, because he now smiled all the more, precisely at the way he'd gotten me to smile and how obviously horrified I was to be doing so. He swallowed me whole."

That is how the text read. And what is interesting about that passage is it displays exactly the kind of transparency that I am talking about. It describes the situation.

But, of course, when I write, "He swallowed me whole," I swallow him whole. So I have the last word. I get to have the Cheshire Cat grin.

The entire unexpurgated version of my Uruguayan reporting can be found in my book A Miracle, A Universe: Settling Accounts with Torturers.

Incidentally, in the end, on November 2, 1994, a jury finally found two of Malcolm’s contested quotes to be false, and one of those to be defamatory, but it also found that she had not in any case acted with reckless disregard for the truth, thereby clearing her of defamation. And that was that. Except that, oh yeah, there was still this.

* * *

Artwalk

Apropos of Everything and Then Some:

David Opdyke Redux

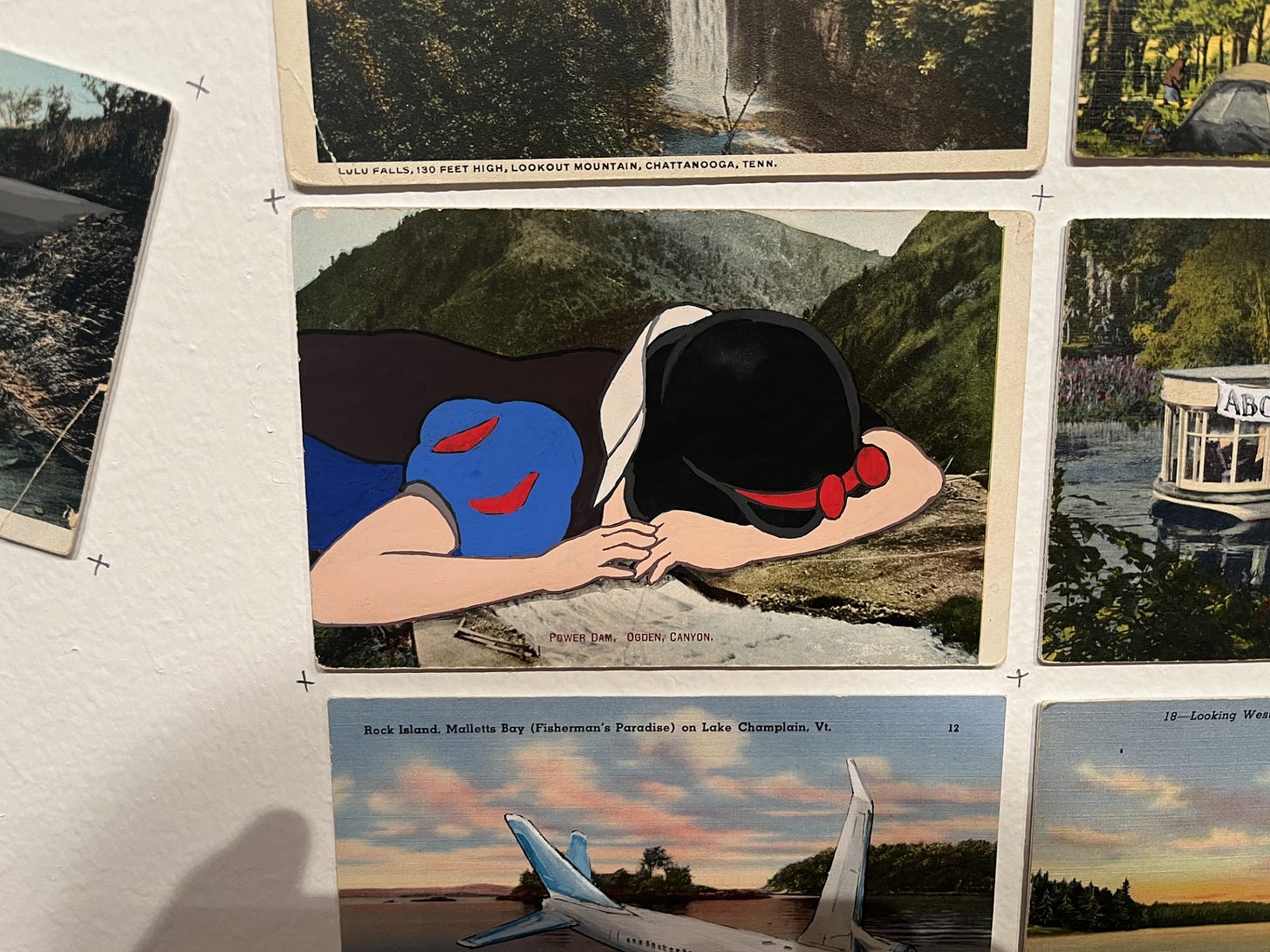

Have any of the rest of you also noticed how almost completely the well-nigh-immediate emergency of climate change has all but disappeared from the center of our concerns amidst the veritable niagara of other calamities our Dear Leader has merrily been visiting upon us, day in and day out? Well, thankfully, our old artist friend David Opdyke has been keeping his eye on the central plotline, and he is back with another show to remind us.

Veterans of the Stack may remember my piece on Opdyke in the Atlantic, around the time of the release of my book on the artist, as touched upon back in Issue 32A, on the occasion of the vernissage of the artist’s then-latest epic retouching of vintage postcards ranged in a feverish combine mural along the long wall at the Museum of Climate Change in Soho.

Well, Opdyke is back with yet another series of such labor-intensive, alarm-stoking and thought-provoking combines, this time at the Christin Tierney Gallery on the 2nd floor at 219 Bowery in Manhattan, through May 10. The show features an array of tweaked single-card one-offs, retro images suddenly tapping clean into the anxious distemper of the current age:

Link to video here.

Images which in turn compound, one upon the next, into ever more vertiginous wall-wide visions of the world to come, if we don’t all somehow summon the will and the gumption and the common purpose to prevent it from doing so.

See video here.

Lavishly praised by the likes of Bill McKibben, Naomi Klein, and Eric Fischl, Opdyke’s work certainly merits repeated viewings, but you better hurry, you only have a few more weeks!

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

NOTE: As we say, Ren will be traveling and professing away during the next month or so, as a result of which offerings on the ’Stack may become a bit attenuated (maybe not), but don’t worry, we will be back again in full bloom come the summer.

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

"The notes were found, Ms. Malcolm said in the affidavit, by her 2-year-old granddaughter, Sophy Tuck, on the night of Aug. 11 in Ms. Malcolm's home in Sheffield, Mass. In Ms. Malcolm's telling, the child had been banging on the piano, then began exploring a nearby bookcase, where she plucked out a thin book with a red cover."

I can't think of another instance in which life imitates art so vividly and mischievously. It's like all her subjects--Freud, Plath, Chekhov, Stein - compressed into one anecdote.