March 2, 2023 : Issue #37

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

For starters, Part One of two on the life and work of Hans Noë, a remarkable heretofore largely unknown 95-year-old architect and sculptor: a Holocaust survivor and a true hidden master. And then a convergent trill from Velasquez’s Surrender at Breda by way of migrating zebras to Chuck Close. Because, why not?

* * *

The Main Event

I’ve been meaning to include this piece for a while now, and for some reason this feels like a good time. My longtime pal Alva Noë, the philosopher of mind and art, now back at Berkeley, had for years—nay, decades—been telling me how I really ought go upstate and visit with his father to see what he was up to; I’d ask why and Alva’d just say how, no really, I just should.

You know how it is, one thing was always leading to another and I never got around to it. But then about six months before Covid time, I took Alva up on his proposal, and went up the Hudson to Garrison, just south of Beacon, to visit with his parents, both now in their nineties—and all I can say is, boy had he been right.

Both of Alva’s parents are remarkable, but what his father had been up to was downright amazing. Another thing led to yet another—a veritable cascade of coincidences—and within the year the work in question was receiving a show, his very first, and I’d been asked to write the catalog. Regarding which more anon, for that’s all part of the story, which follows here, in two parts:

The Long Occluded Mastery of Hans Noë

(Part One)

Visitors to this show may well find themselves asking two questions in rapid succession—Who is this guy, and (given the evident caliber of the work) where the hell has he been all our lives?—and therein hang a whole series of tales, for we would indeed seem to be dealing with the work of a Hidden Master.

Hans Noë was born in 1928 in Czernowitz, a remarkable little town in its own right in the northern part of the far eastern Bukovinian region of what had once been the Austro-Hungarian empire (about eight hundred kilometers due east of Vienna and due south from Vilnius)—with a population of about 250,000, roughly half of them Jewish with the rest a polyglot mixture of Ukrainians, Romanians, Germans and the like, from which was presently to emerge a truly astonishing array of major cultural figures (including the writers Aharon Appelfeld, Paul Celan, and Gregor von Rezzori). His Jewish parents, already sensing the way things were tending, had had the good sense to give their sons German and decidedly non-Jewish sounding names—Hans-Heinz, no less, and then Marcel—which may in some small part account for the fact that they survived the war at all. Their father was a distinguished pediatrician whose preternatural savvy and caution also played their part across the years when the conflict raked back and forth across the town, which went from Soviet-Ukrainian to Nazi-allied Romanian and back again, each regime posing its own set of challenges and hurling forth its own existential terrors and near misses (“It could have happened. // It had to happen. // It happened earlier. Later. // Nearer. Farther off. // It happened but not to you” being the way the late great Krakow poet Wisława Szymborska subsequently characterized a similar passage through those same years. “As a result, because, although, despite. // What would have happened if a hand, a foot // within an inch, a hairsbreadth” and so forth). Decades later, the now 93-year-old Hans described for me just a few of the countless times during those years when his father “gave me life all over again,” including one exceptionally harrowing night when the newly arrived Romanian fascist army torched the magisterial central synagogue just down the street from the family’s apartment and then began looting and making arrests all up and down the block. I asked Noë whether he imagined he had yet further repressed memories from those years of his fraught early adolescence, to which he replied, “How should I know.” (He has little patience for such introspections.) “My problem is what I keep remembering again and again,” he went on, before muttering, “Doubtless, something did not survive that period.”

And yet, somehow, the family as such did survive the war (over two thirds of the Jews of Czernowitz did not), and as Stalin’s army now began determinedly incorporating the region into the Ukrainian SSR, the Noës resolved to flee westward, at first (improbably) into Germany, where for a year young Hans enrolled in “a very good school for applied art,” just outside Frankfurt, where one of his favorite professors was Herman Zapf, who would go on to become a world-renowned calligrapher, and where one of the abiding lessons Hans took was “the difference between people as people and the same people when mobilized into mobs” (one morning, for example, he happened upon his otherwise entirely congenial landlady down in the basement, burning an SS uniform). Eventually, Hans’s father was able to secure the family a refugee visa for entry into the United States, which required a stopover in a transit camp outside Naples, which Hans recalls in near rapturous terms (“The sea, the light, the colors, the spaciousness, how at long last one could breathe!”)

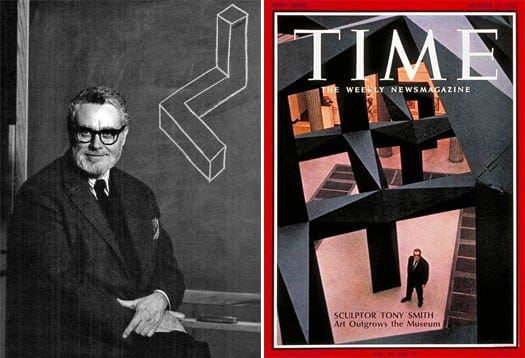

Arriving in New York harbor on Christmas day 1949, the 21-year-old Hans resolved to reinvent himself as an American and while speed-learning English threw himself into various odd jobs as he waited to find out the disposition of his application to Cooper Union, to which he was indeed accepted and began his studies in September 1950. Cooper required that first-year students take a range of introductory courses, and Hans took an instant liking to the instructor in his architecture workshop, one Anthony P. Smith, who in turn seemed to take a decided interest in the young refugee as well, inviting him out to drinks at McSorley’s after class a few weeks later and insisting that Hans just call him Tony (this being Tony Smith, one of the foremost architect-sculptors of the developing downtown era),

and presently inviting him to apprentice with him on various architectural projects of his own (such as erecting a house for the artist Theodoros Stamos). By way of Smith, the young refugee presently began hanging out with many of the luminaries of the burgeoning scene—Pollock and Rothko and Reinhardt and especially Barnett Newman. “When it came to art,” Hans avers, “Tony became my father and Barney my uncle.” (For abstract expressionists, who were deeply engrossed in trying to worry out an authentic existentialist response to life and the possibilities of art in the wake of the war and the Holocaust—the stakes involved in “action painting” and the like—here was a kid who had actually survived the Holocaust itself: you could see the boy’s appeal.)

After leaving Cooper in 1953, Hans was drafted into the army, and several of the cohort came out to see him off to basic training (Smith, a Joyce fanatic, gave Hans his own copy of Finnegans Wake, which Hans claims to have systematically devoured, probably the only person ever to do so blissfully unaware that all those fancifully contortionate Joycean neologisms weren’t ordinary English locutions he simply hadn’t ever yet come upon). The army inventoried Hans’s aptitudes, whereupon they assigned him to a watch repair unit, where he waited out the rest of the Korean War stateside (for which service he was even granted expedited US citizenship). Following his discharge, upon Smith’s urgings, Hans decided to pursue further training as an architect, which is how it came about that a few months later he enrolled at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, where he quickly became the acolyte of a new mentor, the Bauhaus master Mies van der Rohe.

“Tony Smith quite simply changed my life, and in a sense I have lived in his world ever since,” Hans recently told me. “He presented me with a form of life, a way of living, which I hadn’t known existed until he modeled it for me, that of a thinking human being. Now, if Tony extended me a way of life, Mies offered me an idea, the Germanic conception of the Absolute, I suppose, of the need to be constantly aspiring toward perfection, or as close as one can get to it. The classroom exercises at his institute, the sheer expenditures of time that it was expected one lavish on the slightest drawing—at times it could approach insanity. But that, too, registered deeply.”

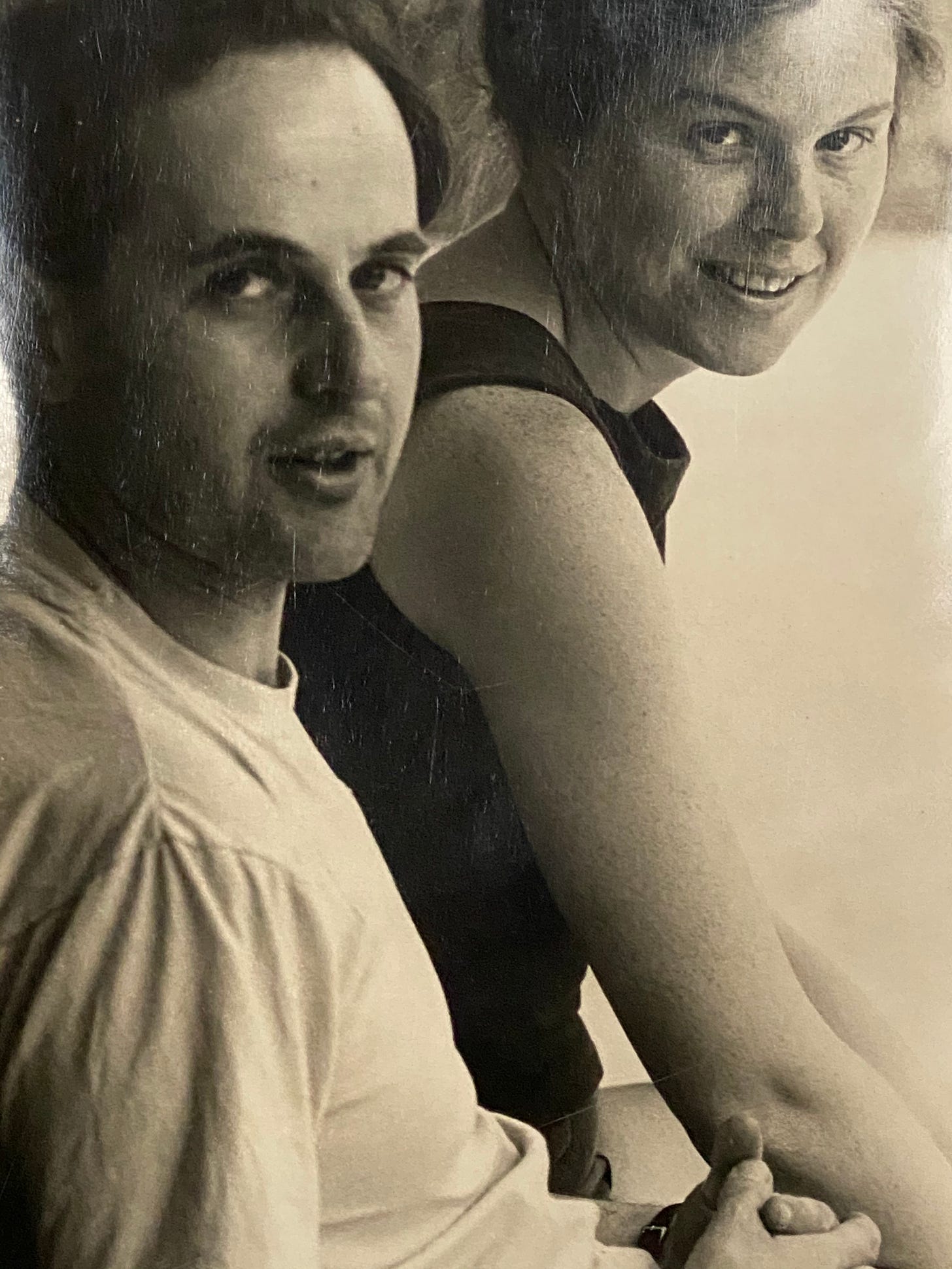

Something else that clearly registered deeply for Hans during those years in Chicago was a fellow student named Judy Baldwin, an aspiring potter, a shiksa out of Long Island (with quite a dramatic life story of her own)—though she’d at first been cold to his advances owing to his German-sounding name (she had no interest in dating Germans so soon after the war) and it was only when he clarified that no, no, he was Jewish that her attitude shifted dramatically. Upon their respective graduations, the couple decided to return to New York, though neither really had a sense of how they were going to make a living. “As for me,” Hans recalls, “I didn’t have the slightest confidence that anyone was out there waiting for me, no sense of my destiny as an architect, or even a clue as to how I might realize such a sense. Still, neither of us had any great material needs, and we could be there for each other, and we just proceeded.”

They presently established themselves in a small back apartment Tony Smith helped them find on La Guardia Place in the West Village (it had earlier been Smith’s office), and Hans began designing and erecting small summer houses out in the then still quite remote Hamptons. “Painting is color,” Hans said to me one day, “sculpture is volume, and architecture is space. Which is to say, first and foremost, interior space: the space to be lived in, not gawked at from outside. The dilemmas it presents are almost impossible in their complexity, and all the more so if one has also to be dealing with clients, a problem I solved, to the extent I was able, by simply eliminating the client altogether, or rather becoming my own client. I would find a cheap property, clear it by hand, and then design and erect the structure on my own, with the help of Judy and a few friends and assistants, all on spec—and then sell the thing and, generally, break even. As it happens, the first one I put up in that manner—I don’t know how it happened, I almost don’t claim credit for it—but the clarity of the solutions, the pacing of the supports, the relation of wall to roof, mediated all around by a high band of windows: seriously, it ranked right up there as one of the finest such homes built by anyone in the last century.” He wasn’t boasting, just stating a fact. “And I was never again able to match it, though I tried.” Where is it, could one go see it? “No,” Hans declared brusquely, decisively, “it no longer exists, almost none of them do.” Whereupon, “That’s not true, Hans,” Judy (who’d been listening in off to the side) intervened. “Several of them still do.” To which Hans insisted, “Not really.” (It quickly became clear that Hans is one of those architects for whom too many interventions, additions, or alterations by subsequent owners and the place simply ceases to exist, at least in any relation to him. “I don’t get it,” he argues. “You buy a painting and you cease liking it, you don’t get to layer in a few extra trees or animals. You buy a book and grow bored, you don’t get to scramble the relations between the existing characters.” Clearly he hasn’t heard of fan fiction. “Only with architecture do people feel they have the right to alter things to their heart’s content.”)

He never really wanted to do anything more ambitious than houses, he tells me. “A house is the biggest thing an architect can still do alone. A school takes a team, and a skyscraper, good lord, an entire office with subcontracting offices below that. But it turns out that to be a success as an architect, even just at the house scale, you have to be more than an inspired creator; you have to be a perpetually churning businessman and tireless self-promoter, and I had none of those other skills, nor, frankly, did I ever wish I had them. I figured that if you did your best work and put up the thing, people would notice it, it would speak for itself, and acclaim would naturally come to you. Turns out it doesn’t work like that.”

We were sitting in the wide, airy study of the upstate Garrison home he built for himself and Judy about twenty years ago (a couple miles inland from the Hudson River, just across from West Point on the other side), one of the few such structures he still acknowledges as his own. It was muggy hot outside but sublimely comfortable within, with no air conditioning required, and hardly any heating in the winter. (“It has to do with the structure’s alignment, parallel, as it happens, to the river, which you can’t see beyond the hills over there, which in turn controls how the breezes run; that and the placement of the eaves jutting out over the patios all around, and then the low slotting of the enveloping windows.”)

What, I asked him, would be his definition of a Noë house? “Oh, I have no idea,” he replied, and mulling the question further, “Basically, I suppose it would be handmade to the extent possible, cheap, the simplest possible solution to the problem posed. In this particular instance, I found this nothing piece of land, walled off about a quarter acre from the surrounding scrub forest wilderness, cleared it out and levelled it flat, and then slotted in the house—all on one story, since I figured we’d need to be able to grow old in it (though we have a basement underneath which you can approach from an outside slope), and then the entry foyer with this open workspace studio here to one side, the living/dining area straight up ahead over there with the kitchen off in the corner, and off to the other side, that long, wide hall with bedrooms and bathrooms and studies all lined up along its right rim—and everything incidentally worked out in consistent multiples of three-foot-four-inches: three-foot-four, or six-foot-eight, or nine-foot-twelve (which is to say ten-foot), a patterning you don’t even notice, though somehow you get a satisfying sense of order.”

He paused and sighed at the fact that in the end he only ever built less than a dozen such houses, total...

Not that he was complaining, he quickly assured me. He and Judy had had an improbably successful life, “truly an instance of the great American dream.” To begin with there had been Judy’s successes, starting with her own eminence in the pottery world, as a highly sought after maker, but also as a teacher across an ever-expanding succession of spaces (“And Hans himself designed and built them all, along with all the wheels and the kilns,” Judy chimed in from the side—“For a while she was my principal client,” Hans concurred) and presently their booming pottery supply business as well. (“At one point,” Judy elaborated, “we had all these vans coursing up and down the Tri-State region, delivering clay and whatnot to universities and YMCAs and all sorts of other such workshop institutions.”)

And then there was the family, their two sons, starting with Alva in 1964, who grew into one of the country’s preeminent philosophers of art and mind, now living and working in Berkeley, with two sons and a daughter of his own; and then Sasha, a few years later, who became a formidable sculptor in his own right, adding three further grandkids.

Which was not to mention Hans’s own uncanny real estate successes, starting out at the nadir of New York’s immiserated decline during the late sixties and early seventies (“FORD TO NYC: DROP DEAD!”), when he bought up a couple largely dilapidated buildings, rehabilitating them personally (in this context, Hans figures he designed another twenty or so lofts and artists’s spaces over the ensuing years), and renting out the resultant storefronts and apartments, all of that just before Soho exploded into the veritable center of the art world. (“A person would have had to be a schmuck not to succeed in such an environment,” Hans insists, though many did not. Key to the city’s rebound, incidentally, were the ministrations of the financier Felix Rohatyn, another scion of Czernowicz.)

As it happened, one of the properties Hans snatched up, at the corner of Prince and Mercer, included at street level a legendary watering hole named Fanelli’s, though by then it was barely open any longer (only a few hours a day) and largely rat-infested: Hans figured he’d decide what to do with that space down the line, but he eventually took to salvaging the diner bar as well (“It’s now the cleanest such establishment in the city, I assure you”) and somehow (“What did I know about barkeeping or running a diner, but gradually I picked up on things”), it became arguably the most happening place in its whole Soho neighborhood. (“I’d just sit over in the corner and watch things unfold.” And who, I wondered, was he to the assembled crowd? “Oh, I was nobody, I assure you, I was anonymous, which is how I always am and how I like things; hell, I am even anonymous to myself,” a response which put me in mind of Kafka’s retort to a similarly impertinent questioner, “What have I in common with the Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself and should just stand very quietly in the corner, content that I am allowed to breathe.”) Hans has in the meantime handed the management of Fanelli’s off to his son Sasha.

The entire time, meanwhile, Hans was keeping his purely creative side engaged by constantly generating his sculptures, or structures, or maquettes—a practice he continues to indulge to this day, even though he still isn’t quite sure what to call the things. He’d never particularly intended to show them or to build them out, or so he kept trying to convince himself. And yet…

TO BE CONTINUED AND CONCLUDED IN OUR NEXT ISSUE

Preview of coming attractions:

Four vantages of a single instance of the uncanny spatial sensibility Hans Noë has been lavishing across his wildly imaginative late-life creative flowering. Check out a video of his own careful unfurling of this astonishing piece here.

* * *

FURTHER CONVERGENT SPECULATIONS

SIGHTLINES AT BREDA / ZEBRAS IN THE DUST / CLOSE EYES

So here we have Velasquez’s extraordinary 1634 painting of The Surrender of Breda at the Prado. The painting portrays the end of the Spanish siege of the (now southern Dutch) town ten years earlier, in 1624. That’s Justinus van Nassau, to the left there at the center of the painting, handing over the keys to the city to the Spanish general Ambrogio Spinola, over to the right. But the longer one looks at the painting, curiously, the more the two commanders seem to fade into the background, the exhausted slouches and faces of the soldiers to either side slowly coming to the fore, that and the completely remarkable geometric splay of the lances above the Spanish troops to the upper right side of the painting.

But then, too, we begin to focus on certain particular faces in the crowd, which is to say the ones that, oddly, seem to have noticed us, returning our stare, one of them to the left, and three of them to the right.

That’s weird, we find ourselves thinking, what are they looking at—and who are we, focusing on them? A splay of sightlines seems to emerge, pegging our intersubjective relationship across time.

A magical play of lines, that is, like nothing so much, perhaps, as those lances up there in the corner.

And now compare this:

A master-shot by the wildlife photographer Paul McCroskey of East African zebras and wildebeests in the midst of their Great Migration, recently shared with me by my dear friend Mort, who tells me he once had the privilege of witnessing its very like.

How, amidst the swirl of line and pattern, the sole zebra who is looking directly at us, there to the center left likewise immediately catches our eye… Actually, there are two of them side by side, both looking out at us, but their shared gaze somehow seems subliminally to blend into a single bifocal stare.

On third thought, there are four (or rather five) that are looking our way, that pair off to the left but then three more to the right, exactly as with the Velasquez (though the bottommost glances of the mother and child—shall we say?—are slightly askew, whereas the father above and just behind the mother has us directly in his sights).

What is it about eyes?

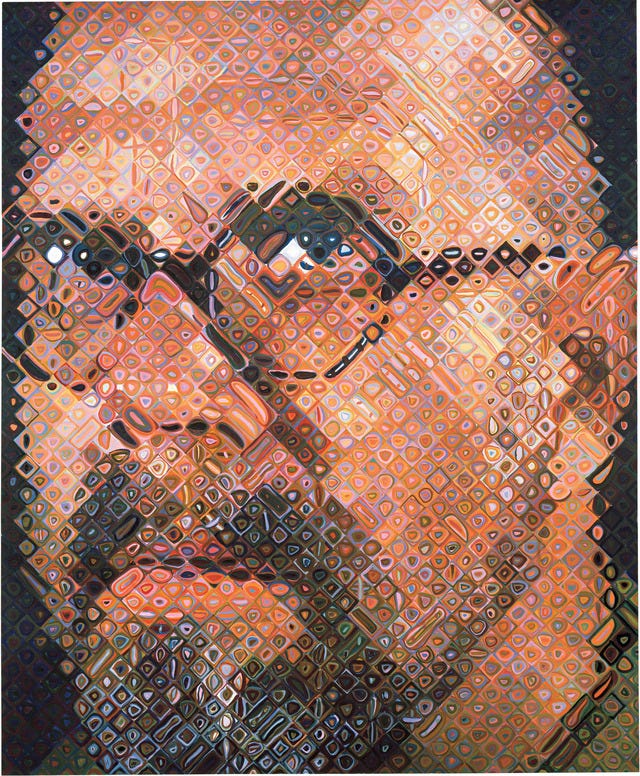

Consider this self portrait of Chuck Close’s, from 1997.

The canvas is covered over with a veritable hive of eye-like ovals (each one embedded in its own rhomboid cell), but we have no difficulty making out the eyes themselves—indeed can’t help but do so, they have us completely nailed—even though the irises actually get spread over three or four such cells. Maybe it’s the single cell of white (the whites of the eyes) that sets them off, but that is not what we look at, or get seen by.

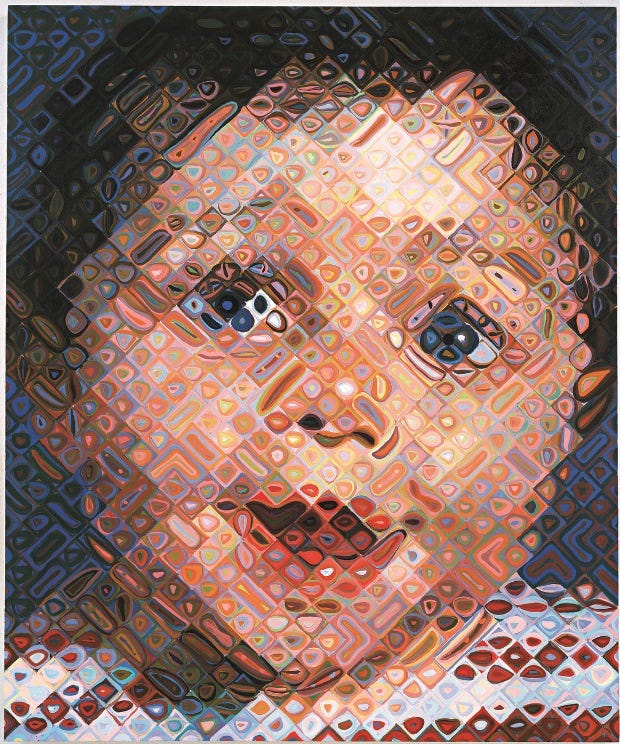

Likewise, and somehow even more so, with this Close portrait of baby Emma from a few years later (2000):

All of which in turn puts me back in mind of that New Yorker talk piece I wrote on the occasion of my daughter’s birth, thirty-six years ago this week, and which I featured back in Issue #23, the one that ended, “My eyes locked on hers, I'd had a sense that I was gazing into origins, the ur-past—that this gaze of hers was welling up at me from deep beyond the past's past. Of course, that sense of things was all wrong, for, eye to eye, it was she who was gazing into the past. I was gazing into the future's future.”

* * *

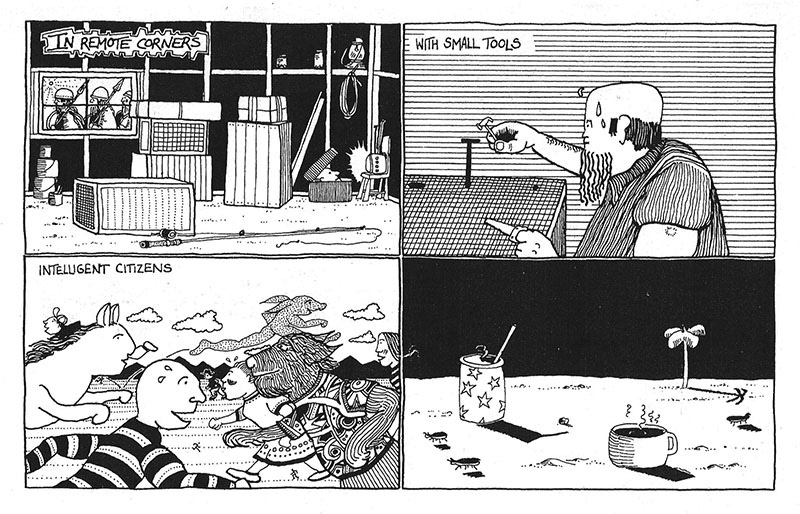

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford

The Animal Mitchell archive .

***

NEXT ISSUE

Part Two of the Noë saga, with an exhilarating sampling from his extraordinary late-life production. Hidden no more…

Beautiful essay, elegant work. I hope it can come to LA sometime.

Fascinating. Thank you.