WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This time out we offer the second and concluding part of our profile of the nonagenarian hidden master Hans Noë, with a rich sampling from his prodigious late-life production. And, as a dramedic chaser, an INDEX SPLENDORUM MINI: a triptych of nail-clipees, and the well-nigh cosmic implications of their turmoil.

* * *

The Main Event

Occluded Mastery of Hans Noë (Part Two)

Last time out, in Issue #37, we were introduced to Hans Noë, a veritable hidden nonagenarian master—the father incidentally of the Berkeley philosopher of art and mind Alva Noë and a sculptor son Sasha (inheritor of his father’s Fanelli’s Bar and Diner in Soho New York)—and learned of his birth in 1928 and upbringing in Czernowicz, along the Bukovinian edge of the old Austro-Hungarian empire, himself the son of a pediatrician who somehow managed to guide his entire immediate family unscathed through the harrowing years of the Holocaust and countervailing Nazi and Soviet occupations and then on to America, where in 1950 Hans secured admission to Cooper Union in New York City. There, he came under the patronage of the great architect and sculptor Tony Smith and through him of such other luminaries of the abstract expressionist scene as Barnett Newman, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock (while they were all yammering on about the existentialist stakes involved in making art after the Holocaust, here was a kid who had actually survived the thing). After Hans had served a stint of stateside service in the military during the Korean War, his mentor Tony Smith urged him to pursue a career in architecture and handed him off to his friend, Mies van der Rohe, in Chicago, from where Hans emerged a few years later, with both a degree and a bride, Judy Baldwin, herself an accomplished potter and ceramicist. During the late Fifties and early Sixties, Hans designed and built a series of residences, mainly in the Hamptons, but his career never really took off. As he noted, to truly succeed in that profession, one needed to be a great architect, a great businessman, and a great self-promoter, and he was pretty much useless in the latter two regards. He bought dilapidated buildings around the then-utterly derelict neighborhood of Soho, converted upper floors to artist lofts, and then rode the updraft of the downtown economy (following the near-bankruptcy of the city in the mid-Seventies) to relative wealth, enough anyway to retire to a home he now built for himself and Judy outside Garrison, south of Beacon, about a mile inland from the Hudson. That was about thirty years ago, and his real career, the hidden secret one, was just about to take off.

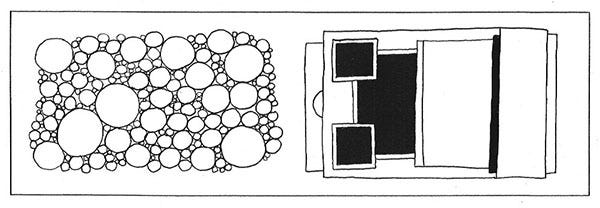

The entire time, meanwhile, Hans was keeping his purely creative side engaged by constantly generating his sculptures, or structures, or maquettes—a practice he continues to indulge to this day, even though he still isn’t quite sure what to call the things. He’d never particularly intended to show them or to build them out, or so he kept trying to convince himself. They were the physical incarnations of passing fancies (“I’d think up possibilities falling asleep at night, and the next day I’d try them out: most failed and I just threw them away, but others I kept and placed along that long shelf over there, and I enjoyed looking at them and moving them about and looking at them again.”)

They formed occasions for palpable thinking, about form and scale and presently color as well. One could readily imagine building them out in a whole range of materials and at a whole range of scales (“although I tended to make them at tabletop size, because people nowadays live in small spaces,” he added, somewhat undercutting his insistence that he never imagined a wider life for them beyond the merely private).

And this business of possible scales is especially interesting, since with many artists (one thinks of Richard Serra, for example, and his torqued ellipses), the maquette models really only work when expanded to certain, usually quite grand, scales—which may not be the case with Noë’s (though one certainly does like to speculate on what they might be like, thus expanded).

“In any case,” Hans insists, “they and for that matter all of my life work has consisted in a working through of just one thought,” which may or may not be true, though there are definitely certain specific themes that keep recurring (and judging from photos of the festooned shelves of his studio from back in the seventies, have been doing so for decades).

There is, for example, “the truncated tetrahedron” as he calls one particularly confounding solid, which appears to have made its first appearance in his proposal for a UN office building in Vienna back in 1959.

Imagine a cube: now, create a rectangle consisting of half the area of the top face and center that rectangle, and center a similarly sized rectangle on the cube’s bottom face, only lined up perpendicularly to the one above. Now slice out the in-leaning trapezoids connecting the two short sides of the rectangle up top to the two long sides down below, and the two long sides up above to the two short sides down below. All of which should create a solid with tapering facing trapezoidal sides on one side and widening trapezoidal sides on the other.

Now create eight such boxy solids and stack them one atop the next, totem pole style, and from a certain distance, and at a certain angle, the two sides of the standing structure will read as knife-sharp edges running straight up vertical from the perpendicular ground, while from another angle the two vertical sides of the tower will seem to weave in and out sawtooth-like, reading (correctly) as zig-zags all around.

The whole thing affording a not so distant allusion to the Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column, Brancusi having been born in Hobitza, on the other side of Romania, about 400 miles south of Noë’s Czernowicz.

Meanwhile, over the years, Noë has discovered dozens of other amazing visual tricks that the confounding solid, by itself or in combination, can perform.

*

Likewise with a yellow equilateral triangle floating at roughly eyelevel, one of its sharp vertices aimed straight at the viewer, while down below, at floor level, an equal-sized triangle points away from the viewer, as it were, with one of its flat lengths exposed to the viewer’s gaze.

Now, imagine the solid created when you connect the point above to the two edges of the length below, and the vertices to either side of the length below to the obverse lengths of the lines above stretching back from the viewer-facing vertex, and so forth, cat’s cradle-like, all around the emerging solid. The resultant structure (Hans’s reconceptualization, he acknowledges, of an onetime idea of Smith’s) would consist of equilateral triangles above and below, with six elongated triangles encircling the building’s sides, alternatively tapering up and down, such that every single one of the building’s floors would consist of varying configurations of three wider and three narrower sides, except for the one at the very middle of the structure, which would resolve into a perfect hexagon. In addition, viewed from almost any side, the shape would give the illusion—but only the illusion—that the whole thing was leaning so precipitously that it was about to fall over. Which it wasn’t. Go figure.

(Hans had thought about submitting the structure as a proposal for the World Trade Center’s reconstruction but never got around to it; curiously, the winning proposal resembles Hans’s idea somewhat, but, being based on squares at the top and bottom instead of triangles evinces none of the delightfully baffling effects of Hans’s version.)

Meanwhile, though, take two such structures (at smaller scale if you prefer) and place them vertically one on top of the other, and that structure will suddenly appear impossibly cinched at its “waist,” no matter how you turn it—except that with each partial turn, at a certain point, the side flanks will suddenly appear to line up perfectly, presenting a standard double-tall rectangular structure.

And the thing is, the impossible cinching effect notwithstanding, the whole thing would also work perfectly well as skyscraper, built around an entirely conventional core running straight up and down through the middle of its interior. And just try to figure that.

Other sorts of structures and variations have been proliferating in fertile profusion across Noë’s shelves, as I say, for years now (including a recent series of variously bent Matisse-like cut-out collages),

with Noë resigned to their being ever-confined to his private amusement, when suddenly, a few months (now years) back...

*

So what happened was that about twenty years ago, real estate developer Phil Aarons and his psychiatrist wife, Shelley, bought a splendid little house up on spit of beachfront just beyond the Springs, and they grew increasingly intrigued by the place’s origins, what with the way it kept revealing ever more intriguingly intelligent vistas and details—who on earth had designed the thing?—

so they launched into a years-long casual effort to determine the place’s architect, all to no avail.

Until one day, while Phil was out checking his mailbox, a woman walking by on the beachfront road happily announced, “My father-in-law designed your house”—the woman being Sasha’s wife, Meredith (they owned a place of their own just up the road). Long story short, but the couple (who incidentally are sponsoring supporters of both Printed Matter in Chelsea and a not-for-profit exhibition space called the Fireplace Project in a converted garage across the street from the Pollock-Krasner House in the Hamptons) presently contacted Hans and his sons, and quickly arranged for a whole show devoted to Hans’s work at that Fireplace Project, and in the event, Hans was actually proving far from indifferent.

Indeed, as he told me late one night on yet another of my visits up to Garrison, the prospect had been provoking a whole revision of the story he’s long been telling himself about his life. “I used to imagine my general distaste for self-promotion and my indifference toward fame as sort of emblematic of a certain kind of moral or at any rate aesthetic superiority. With high considered self-regard, I was refusing to enter into that whole delusional rat race. But I’m no longer so sure. I think rather that my problem may simply have been one of fear, a prolonged form of PTSD, as it were, with its roots wending back to my experience of the war, when survival enforced an entire regime of perpetual hiding, since any and every calling of attention to oneself could so easily have proven fatal not only for myself but for my entire family. And maybe it’s just that I never got over that way of being in the world.”

Maybe it hadn’t so much been a question of a Hidden Master as of a hiding one.

And now, at age 93 (“enormous changes at the last minute,” in the words of that other doyenne of the Eastern European diaspora, the late Grace Paley), the master in question was about to get flushed out.

Good for all of us: Talk about just desserts.

*

And indeed the show did open a few months later and was widely attended and viewed, though perhaps not as much as it might have otherwise been since we were still in the craw of COVID time. I myself contributed a version of the above text by way of catalog essay. And even the relatively limited exposure provoked a sudden upwelling of renewed creative work on Hans’s part. A few years have passed (Hans is now 95 years old, and claims finally to be slowing down) but plans are afoot for further shows, notably in New York City itself, and we will keep you apprised. For that matter, do let us know if you know of any other venues that might be interested.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford…

The Animal Mitchell archive .

* * *

INDEX SPLENDORUM MINI

A nailclip triptych

I have no idea where I got this one, or I should say these three, they just came floating over the transom the other day, I can’t remember from where—the Stoic, the Hysteric and the Drama Queen—I suspect some of you will have already seen it, but then you too will be able to share my delight in being able to share it with the rest of our cohort. Link through here.

Now, watch the video one more time, only this time bearing in mind the classic metaphor from early on in his Basin and Range book (1982) in which John McPhee tried to encapsulate the sheer scale and expanse of deep time: "Consider the earth's history as the old measure of the English yard, the distance from the king's nose to the tip of his outstretched hand. One stroke of a nail file on his middle finger erases human history."

And party on!

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Another season, alas, of several balls all tumbling in mid-air, so we’ll just have to wait and see which one lands first, but, don’t worry, they’re all quite cool and the results should be swell.

fun issue. and THE ANIMAL MITCHELL "cartoon" this time is exquisitely funny.