WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Biden flounders, the Court rampages, the planet broils, Ren rants; Koestler on Weimar Germany; Hoffer on the True Leader; and a babe at the very brink…

REN RANTS

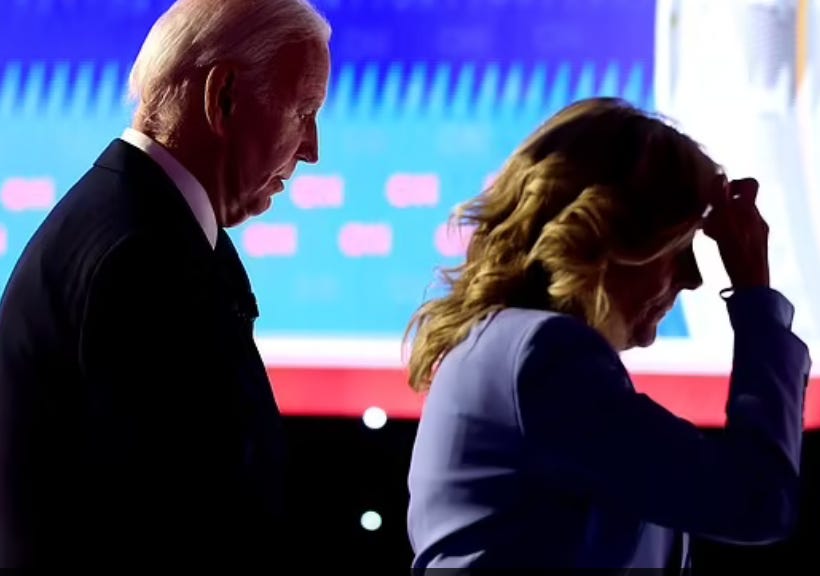

Is it not even a full week since that god-awful debate last Thursday? Or, let me rephrase that, has it only been a single week? Doesn’t time just fly/grind by when you’re witnessing—nay, participating in—the mass-nervous breakdown of your country’s entire political system?

Still, it’s perhaps worth looking back on the first minutes of that debate, especially if you never actually watched it (as you can here), if only to recall how heart-rending, heart-breaking, and all around infuriating it all was. Especially infuriating in how the manifestly evident deterioration in Biden’s capacities had been being so relentlessly denied—and is still being denied as we go to press—by the bad faith staff and family members ranged all around the poor guy.

1. But even more so—infuriating, that is—because the calamitous debacle momentarily drew our attention away from arguably the single most consequential event, in world historical terms, of this week, this year, and perhaps this entire century (or at any rate the one to come), which took place the following morning. Which is to say the Supreme Court’s so-called Chevron decision, in which the Court’s six-person far-right conservative supermajority summarily stripped all expert federal, state, and local administrators of the regulatory capacities assigned them by their respective legislatures, instead declaring that every single one of their determinations could now be second-guessed by judges up and down the national system by way of a coming surge of lawsuits mounted by the very same billionaires (largely fossil-fuel tycoons like the Koch brothers) who have spent the past several decades engineering the arrival of precisely the six-person majority that now delivered that opinion and will ultimately get to decide on all those eventual lawsuits. Decades of precedent mandating judicial deference to such expert administrative determinations was now swept aside in one fell swoop (in a decision in which our new expert overlords couldn’t even get the pertinent distinction between nitrous oxide and nitrogen oxide right in their own pontifications). The decision will have immediate implications for the ongoing safety of the country’s food and drug supply, the purity of the water and the clarity of the air, labor rights and work conditions, anti-trust provisions, how to temper the surge of artificial intelligence and corporate invasions of individual privacy, etc. etc. But the most portentous implications of the court’s decision will have to do with our country’s capacity to participate in confronting the world’s exponentially worsening climate crisis.

Some of Biden’s greatest achievements came in the way he somehow managed to secure unprecedented legislative advances in that regard—all of which, it would seem, are now in dire jeopardy. And if the United States is now going to unilaterally absent itself from confronting that challenge, what chance will the rest of the world have in doing so?

2. Perhaps most infuriating of all was the egregious illegitimacy of the six-person court majority that rendered the decision.

As is well understood by most observers, across the eight national elections since that of 1988, Republicans secured a majority of the popular vote (the only such electoral gauge of national consensus) in precisely one (Bush Two’s second election, which took place in the immediate wake of 9/11); notwithstanding which, minoritarian Republican presidents somehow managed to forge a court with that two-third’s arch-conservative super-majority, in part of course through the sly machinations of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell who wrested one appointment clean out of Obama’s hands while jamming through another at the very tail end of Trump’s term. Speaking of which, according to a recent piece in the Washington Post, owing to the outrageous skew in popular representation evinced by a Senate in which Wyoming (pop. 575,000), say, gets the same two votes as California (pop. 39,500,000), five of the six Republican-appointed justices ended up being confirmed to their lifetime sinecures by Senators representing less than a majority of the country’s total voters (Thomas 49%, Alito 50%, Gorsuch 45%, Kavanaugh 44%, and Barrett 48%). By contrast, the Democrat-appointed justices received the votes of Senators representing 73% (Sotomayor), 65% (Kagan), and 57% (Jackson) of the country’s total population respectively. And yet—or should I say, precisely so?—these minoritarian justices systematically set to work dismantling all manner of lower-case democratic initiatives, from campaign finance through voting rights to gerrymandering reform.

3. Perhaps even more infuriating than that is how all of this was well understood almost four years ago as Biden was taking office, and there was at the time a rising groundswell of interest, especially in the wake of Trump-McConnell’s then-recent clearly illegitimate packing of the court, in doing something about it. By, say, increasing the court from nine to thirteen members, or imposing staggered eighteen-year term limits on all the justices (starting with Thomas, the most senior and most obviously corrupt), or even considering mounting impeachment proceedings against the latter. All of which President Biden himself, the most sublimely institutionalist of all our recent presidents (and one whom, in his earlier incarnation as head of the Senate judiciary committee, was perhaps more responsible than anyone else for allowing Thomas’s deeply problematic nomination to eke through) summarily swept off the table: not his style.

4. And we now see where that timorous course has beached us—be it with regard to gun control or abortion rights or presidential immunity or all the rest, and, yes, perhaps worst of all, with regard to that capacity for urgently addressing climate change. Surely that general crisis of judicial legitimacy needs to rise to the forefront of the coming campaign; and just as obviously, the current president, no matter his earlier accomplishments, is incapable of rising to that, or for that matter any, rhetorical challenge.

5. But all is not lost. With every passing hour, it becomes clearer and clearer that Biden will not be the candidate; for that matter it is no longer even clear that he will still be president in a few weeks. He may retire, lending his vice president the incumbency. Even if he does though, it is not clear that she should secure the candidacy as simply as that. As has been widely discussed, there are a wealth of plausible candidates to choose from. And the coming party convention in Chicago could offer the party a chance to do just that.

The five or six most plausible of them (including Harris), as determined by some agreed-upon criteria (polling status or the like), could each be invited to address the convention for, say, twenty minutes on its first night; they would be encouraged not to take aim at each other but rather to frame their own sense of the stakes involved in the coming race and their forward-looking vision with regard to upcoming national challenges. (I for one would be looking to hear about what ought be done with regard to that rampaging rogue runaway Court.) There could follow a few days of floor-politicking—just imagine the wall-to-wall media coverage—leading finally to a single ranked-choice ballot (no need for the internecine warfare of multiple ballots). The resultant candidate—a new young, relatively rested fresh face—would barrel out of the convention with seven or eight weeks to mount a spirited campaign. The rest of the party could rise to the occasion as well, in races up and down the ballot. I’d give them all a pretty good chance.

6. So that: yeah, something like that. Or else we can all just keep sleepwalking down Weimar Boulevard to our collective doom.

* * *

Speaking of which

ARTHUR KOESTLER ON LATE WEIMAR

A few weeks back, I happened to be in London visiting with our old-friend-of-the-Cabinet Walter Murch at the pied-a-terre he shares with his wife Aggie, soft by Primrose Hill, and we took to discussing the already-then quite dire political prospect back home. He asked me whether I’d ever read Arthur Koestler on the last days of the Weimar regime, pulling his copy of the Jewish Hungarian émigré’s 1951 midlife autobiography Arrow in the Blue off his shelf. Now, Koestler is a famously complicated character, but boy could he write (see for example these four pages from elsewhere in the same book, on his reporting trip aboard a Graf Zeppelin expedition to the Arctic). And boy could he foment (see, for example, his wildly revisionist—and granted, to some extent superseded—take on the history of astronomical speculation from the Babylonians through Galileo, The Sleepwalkers, a longtime favorite of both Walter’s and mine). And boy could he flat-out report, as in this distressingly pertinent evocation of the last years of the Weimar regime as seen from Berlin, where he had arrived in 1930, age twenty-five, to take up a position as the new science correspondent for the Ullstein media empire.

LIBERAL GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG

(Excerpts from Chapter 27 of Koestler’s Arrow in the Blue — for the chapter in its entirety, see here.)

I arrived in Berlin on the day of the fateful Reichstag elections, 14th September 1930, {...} the day which heralded the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the age of barbarism in Europe.

Up to 14th September, the National Socialist Party had twelve seats in the German Parliament. After that day, one hundred and seven. The parties of the Centre were crushed. The Democratic Party had all but vanished. The Socialists had lost nine of their seats. The Communists had increased their vote by 40 per cent, the Nazis by 800 per cent. The final show-down was approaching. It came thirty months later.

The day after the elections, I took up my new job in the imposing building in the Kochstrasse. Everybody there was still dazed. I had to pay courtesy calls on the editors of the four daily papers and of a dozen weeklies and monthlies, all housed on the second and third floors of that one labyrinthine building. They shook hands limply, with absent looks. One or two of them said with a wry smile: 'Why on earth didn't you stay on in Paris?' The arrival of a new Science editor at that particular moment struck everybody as exceedingly funny.

After a few days the panic subsided and the people in the Kochstrasse, as everywhere else in Germany, settled down to carry on business as usual in a country that had become a minefield. The ticking of the time-fuses was sometimes more audible, sometimes less. One soon became accustomed to it, and there were still thirty months to go. {...}

More than half the people in the Kochstrasse building were Jews. The other half did not fare much better later on. The Ullstein crowd was Dr. Goebbels's bête noire. We stood for everything that he hated: 'rootless cosmopolitanism,' 'judeo-pacifism,' 'pluto-democracy,' 'Western decadence,' 'gutter literature.' Mutatis mutandis....

Individuals reacted to the approaching apocalypse according to their varied temperaments. There were the professional optimists and the constitutional optimists. The former fooled their readers; the latter fooled themselves. There were those who said: 'They can't be a bad as all that.' And those who said: 'They are too weak, they can't start anything.' And those who said: 'They are too strong, we must appease them.' And those who said: 'You are frightened of a bogey, you've got a persecution mania, you are hysterical.' And those who said: 'Hatred doesn't lead anywhere, one must meet them with sympathy and understanding.' And those who said simply: 'I refuse to believe it.'

Thirty months is a long time. There were ups and downs. Elections followed each other at an increasingly feverish rhythm. The Nazis' votes increased by leaps and bounds, but in between they suffered minor setbacks and everybody breathed a little more freely. There was the great purge in the party which brought the end of Gregor Strasser and which was said to have weakened them to such an extent that they were incapable of action. There was a time when the democratic parties seemed to have awakened from their complacency and the Prussian police actually arrested several Brownshirts. And there was also a minor electoral defeat of Hitler in November '32, which caused a last surge of euphoria just before the end came.

After the event, people asked themselves: How could we have been such fools to twiddle our thumbs when the outcome was so obvious? The answer is that there were ups and downs and that it took thirty months, and that, owing to the inertia of human imagination, to most people it wasn't obvious at all. {...}

In my memory this period appears telescoped into a continuous sequence of events: the oscillations of the curve between hope and despair are no longer distinguishable, only the steady descent into the abyss—gradual at first, then gathering momentum, and ending in rapid, headlong fall. {…}

The building in the Kochstrasse became a place of fear and insecurity which again reflected the fear and insecurity of the country in general. We still walked the long sound-proof corridors with the important air of cabinet ministers but we covertly watched each other, wondering whose turn would come next. In some cases the colleagues of a man knew that he was due for the axe while the victim himself was still strutting among them ignorant of his fate. The situation was summed up in a gruesome joke which at that time circulated through all editorial rooms. It is the only Chinese joke which I have heard and worth telling, for it is symbolic of the atmosphere of the German Republic during its last months.

Under the reign of the second Emperor of the Ming Dynasty there lived an executioner by the name of Wang Lun. He was a master of his art and his fame spread through all the provinces of the Empire. There were many executions in those days, and sometimes there were as many as fifteen or twenty men to be beheaded at one session. Wang Lun's habit was to stand at the foot of the scaffold with an engaging smile, hiding his curved sword behind his back, and while whistling a pleasant tune, to behead his victim with a swift movement as he walked up the scaffold.

Now this Wang Lun had one secret ambition in his life, but it took him fifty years of strenuous effort to realize it. His ambition was to be able to behead a person with a stroke so swift that, in accordance with the law of inertia, the victim's head would remain poised on his trunk, in the same manner as a plate remains undisturbed on the table if the tablecloth is pulled out with a sudden jerk.

Wang Lun's great moment came in the seventy-eighth year of his life. On that memorable day he had to dispatch sixteen clients from this world of shadows to their ancestors. He stood as usual at the foot of the scaffold, and eleven shaven heads had already rolled into the dust after his inimitable master-stroke. His triumph came with the twelfth man. When this man began to ascend the steps of the scaffold, Wang Lun's sword flashed with such lightning speed across his neck that the man's head remained where it had been before, and he continued to walk up the steps without knowing what had happened. When he reached the top of the scaffold, the man addressed Wang Lun as follows:

'O cruel Wang Lun, why do you prolong my agony of waiting when you dealt with the others with such merciful and amiable speed?’

When he heard these words, Wang Lun knew that the work of his life had been accomplished. A serene smile appeared on his features; then he said with exquisite courtesy to the waiting man:

'Just kindly nod, please.'

We walked around the hushed corridors of our citadel of German democracy, greeting each other with a grinning ‘Kindly nod, please.’ And we fingered the back of our necks to make sure that the head was still solidly attached to it. {…}

* * *

WALTER MURCH ON ERIC HOFFER ON THE TRUE LEADER

A few days after I’d left London, I got an email from Walter, taking up our conversation, as it were, where we had left off. He began by citing the legendary longshoreman-philosopher Eric Hoffer’s book The True Believer.

MURCH:

”When this book was published, in 1951, Trump was five years old.

“But here Hoffer is, on page 114, describing the essential attributes of the leader of a mass movement.”

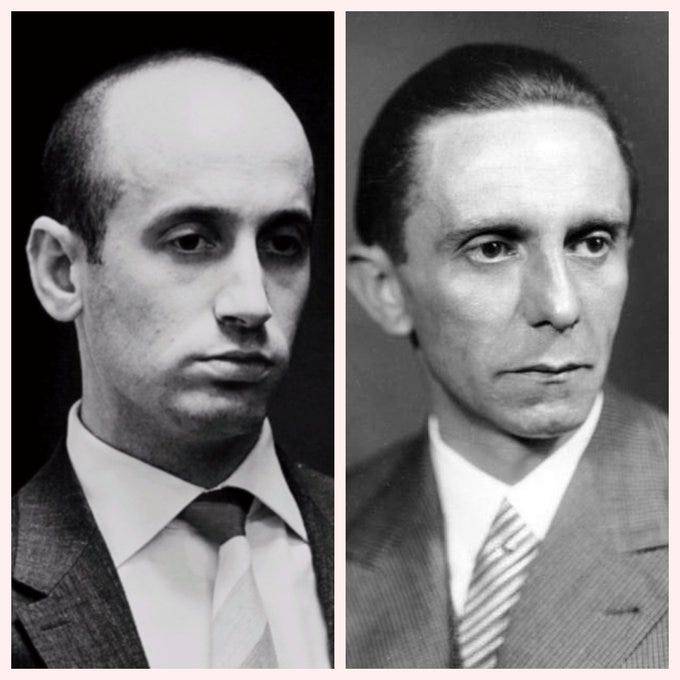

Exceptional intelligence, noble character and originality seem neither indispensable nor perhaps desirable. The main requirements seem to be: audacity and a joy in defiance; an iron will; a fanatical conviction that he is in possession of the one and only truth; faith in his destiny and luck; a capacity for passionate hatred; contempt for the present; a cunning estimate of human nature; a delight in symbols (spectacles and ceremonials); unbounded brazenness which finds expression in a disregard of consistency and fairness; a recognition that the innermost craving of a following is for communion and that there can never be too much of it; a capacity for winning and holding the utmost loyalty of a group of able lieutenants.

This last faculty is one of the most essential and elusive. The uncanny powers of a leader manifest themselves not so much in the hold he has on the masses as in his ability to dominate and almost bewitch a small group of able men. These men must be fearless, proud, intelligent and capable of organizing and running large-scale undertakings, and yet they must submit wholly to the will of the leader, draw their inspiration and driving force from him, and glory in this submission.

Not all the qualities enumerated above are equally essential. The most decisive for the effectiveness of a mass movement leader seem to be audacity, fanatical faith in a holy cause, an awareness of the importance of a close-knit collectivity, and, above all, the ability to evoke fervent devotion in a group of able lieutenants.

“What Trump seems to lack,” Murch went on, “given his performance as President, is the faculty that Hoffer calls ‘one of the most essential and elusive: the capacity for winning and holding the utmost loyalty of a group of able lieutenants.’”

{In this context, see Fintan O’Toole’s devastating piece, “Like ‘Being Friends with a Hurricane’” in the current New York Review of Books.}

“Trump certainly can hold the loyalty of his base (‘I could shoot somebody on Fifth Avenue and I wouldn’t lose any voters.’). But during his Presidency he did not succeed in ‘holding the utmost loyalty of a group of able lieutenants.’ With the emphasis on the word ‘able.’

“We will see in the next five months whether he has developed that capacity.

“Stephen Miller, for one, certainly can be described as glorying in his submission to Trump.”

* * *

INDEX SPLENDORUM

We began this issue of our Cabinet with an unsettling vision of the tide of cogency, articulateness, vividness of presence, the capacity for subtler intellectual discriminations—all of them seemingly streaming away with the inevitable drift into old age: a dark prospect indeed given the stakes involved in the coming election. But let’s end on the far other side, with the happy vision of those precise capacities—for cogency, conviction, articulation, vividness, personality, emphasis—all pouring in as an infant totters deliciously toward toddlerhood (as captured in a TikTok posting that seems to be making the rounds—I myself got it from off my Australian cousin Nic Gruen’s most recent aggregator Substack—tap image to activate video):

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Talk about a blossoming theory of mind ! But a little uncanny how similar the two end up sounding. The old man, the young babe: the tide going out—the tide coming in. And yet it is worth constantly reminding ourselves that in the end the coming election is about the world that child is going to be inheriting (or not)—that that, and not the entrainments of old age and old pride and old grievance, is what we all have to keep at the forefront of our civic consciousness as we stumble across the months ahead.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

This note of recollection just received from Robert Krulwich:

Hey,

Reading your Village Voice profile of Mel Brooks, I want to write down something that happened -- at least I think it happened - in the mens' department at Brooks Brothers on Madison Avenue around 1963. I was there one afternoon to buy shoes and the salesman was showing me 'oxfords', soft leather footwear with little dots hand punched into the surface, something that a banker or under secretary of state might wear. The thing was I was in high school so these shoes were a reach for me, but the salesman was saying I was ready and I was on my feet, looking down at one of those low-on-the-floor mirrors when another customer, an older man about five seats to my left, began looking at me, then at my feet, then at my shoes and began making noises, not words, exactly, but grunts -- I'm not sure he was addressing me or the salesman -- but he was shaking his head and saying "no, no, no..." and I had no idea who this guy was, but the salesman, instead of being annoyed looked a little giddy and kept moving his eyes from the man back to me, as if to say, "Isn't this fantastic!!" while I was thinking "who is this guy and why does he have an opinion about my shoes?" until, a few seconds later, the man got up, moved four seats over so now he was right behind me sharing my mirror and then he sort of elbowed my salesman aside so he could rummage through the boxes of shoes to announce which ones were out of the question, which were acceptable and, seizing one pair -- "This!" he announced is "the best!" trumpeted loud enough for everyone on the sales floor to hear, and he told the salesman to wrap up the pair he liked and make the others all go away.

I don't believe he ever said anything directly to me. What happened after that is a little blurry. I think I retreated, trying to ignore what had just gone on, mumbling something about having to 'think it over' and planning, which I did, to come back an hour later when that guy was gone and I could do what I wanted without all this kibbutzing, which, by the way, is what it felt like. I'd been to Grossingers and had stood in the lobby while 'tumlers' made fun of guests on the registration line and pulled bananas out of peoples' ears and this guy, I thought, was one of those, though finding him in Brooks Brothers was a little like finding a penguin in the Sahara. I remember, or think I remember, coming back an hour or so later, getting the shoes I wanted, which weren't the ones he liked and went home and kept wondering who that man was until...well, two things happened. First the shoes I didn't want, didn't order and didn't pay for arrived at my home, to me, at my parents' address and second, that the invoice from Brooks Brothers said the sender was someone named "Mel Brooks", a name recognized by my mother. "Why would Mel Brooks be buying you shoes?" she asked me. I didn't have an answer. I still don't. I don't know how he got my name, though Brooks Brothers had my address, I don't know why they let Mel (I guess I can call him that) use private information to send me a gift and how to explain his interest, my salesman's smile, the free shoes, why or why he was he so adamant? Sometimes, wandering through life, things happen that never get explained, that stay in a fuzzy space between "it happened" and "I'm not sure it happened." And that, Ren, is my Mel Brooks story.

(A thought: maybe he was a distant cousin to the original gentile Brooks Brothers and had family privileges. Maybe they'd let the yiddish Brooks do yiddishkeit things on the salesfloor because....I don't know. I don't even know why I'm writing you this. I guess it was your article that got me going.) .

I read what you send from top to bottom, even things I've read before.

And I'm a subscriber!!

Robert K.

Dear Ren! Bravo! Profoundly wise and, as always, profoundly informed.

Here's my humble contribution/solution to the Supreme Court high treason IMMUNITY CASE. Stupidly trying to proclaim their Hitler-like master, Donald, untouchable and above the USA Law, they have, (perhaps unwittingly?), proclaimed the current President, Jo Biden, the first KING in the USA history - King Jo I, and this country a new KINGDOM, replacing our traditional REPUBLIC. Biden should, now and immediately, use his new royal powers and prerogatives and arrest the traitor and insurrectionist, Donald Trump, with most of his co-insurrectionists, committing them to life imprisonment, in high-security US prisons. King Jo I still has full six months to carry out this excellent plan, after whose implementation, he can easily "abdicate," as a proper king, and reestablish the good old USA Republic.

Just a thought... :-)