WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

A trip down memory lane to the fraught high anxiety of Ronald Reagan in April 1981 and, before that, Mel Brooks at Christmastide 1979.

* * *

NEWS BREAKING (ALL AROUND US, TO SMITHEREENS)

What a week, geesh. Last Friday it was getting hard to tell which of our two presumptive presidential candidates had taken to behaving the more monarchically—Trump with his newfound royal immunity, courtesy of his loyal vassals at the Supreme Court and the Florida circuit (and don’t you just know that if Trump does win, he will be appointing Judge Aileen Cannon as his attorney general?)—or Biden, who answers, as he kept mumblingly assuring us all week, only to himself, or else to the Lord Almighty who he doubted was going to be intervening anytime soon. Then came Saturday evening when, to hear Trump tell it, He most assuredly did intervene, whereupon the Dear Leader’s minions began ramping up their characterizations of their striding hero from monarchial to downright messianic.

Such that there we seemed to be headed, as we went to press this week, barreling toward an election which (unless somebody or Somebody quickly changes their mind) will effectively be pitting a latter-day George III against a hyperventilating Richard the Third—that’s going to be the choice, folks: God help us.

Anyway, the day before the assassination attempt (and by the way, isn’t the point of the messiah story that God didn’t intervene to stop it?)—anyway, I was foraging through my back files looking for a piece I had composed on Mel Brooks back in 1979 (it happened to be his 98th birthday last week as well and I was trying to remember what I’d written), regarding which see below. But in so doing, I happened to come upon the unpublished typescript of a piece I composed in the immediate aftermath of the attempt on Ronald Reagan’s life in 1981, which within a day suddenly took on eerily renewed pertinence. It began like this:

HIS IMAGE WAS SHOT

(April 1981)

Okay, let me see if I got this straight now. On the morning of the Motion Picture Academy Awards presentation, a former Screen Actors Guild president, now president of the United States, walks out of a convention of union officials, where he has just defended a budget policy which may well condemn thousands of real people to real hardship, walks out of a building and is shot at, with real bullets, by a man who apparently thinks he’s in some sort of movie. No, wait, that’s not quite right. The shootist, it subsequently appears, unloads his .22-caliber pistol into the briskly passing presidential entourage in order to catch the attention of his otherwise oblivious love object, a young actress who several years back played a screen role as love interest to a would-be assassin. “If you don’t love me,” our shootist’s role model had warned the girl, “I’m going to kill the president.” Or anyway, that’s how the shootist remembers the scene. In the film version, the assassin’s confusion somehow derived from his experiences as a veteran of a particularly psychotic recent war. Our real-life shootist had no such alibi. It almost appeared as if he’d just been to too many movies: indeed, a few months earlier, it presently came to light, he’d apparently gone to Nashville, site of another assassination film, just around the time the president’s entourage had come caroming through town on a campaign swing.

Okay, so the president gets shot, and sure enough, it’s all on camera. Hell, the shootist comes barreling out from right among the cameras, and as he’s caught by the Secret Service he’s caught on TV. Three different networks give us three different camera angles. For the rest of the afternoon we get to watch them all, over and over again. It’s like looking at dailies. One of the sequences is unusable—hell, you can see the microphone boom bobbing around right there in the middle of the frame—but then again, maybe we should save it: paradoxically it lends the scene a certain added realism. The shootist, anyway, has gotten his wish: he’s sent his heartthrob a valentine. He’s become as real as her…

And should you want, you can read the rest of it here.

Meanwhile, if things aren’t yet quite surreal enough for you, there’s this just in, over at the Daily Beast:

* * *

The Main Event

FROM THE ARCHIVES

IS MEL BROOKS GOING CRAZY?

Village Voice, December 26, 1977

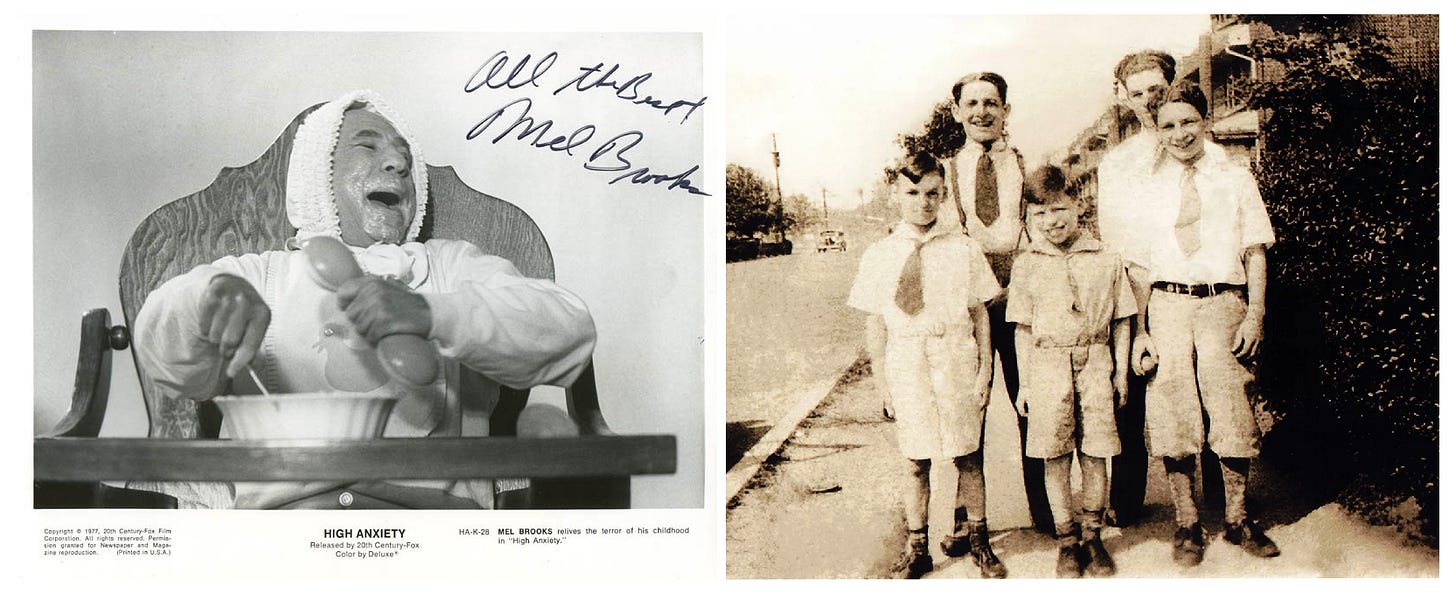

As I say, the incomparable Mel Brooks turned 98 last month and it got me to thinking, because as it happens he proved the subject of the very first profile I ever published in a national magazine, just a few years out of college. As it further happened at the time, a high school friend of mine, the equally incomparable Stuart Cornfeld had recently joined Mel’s production team (he’d been the one who got Mel to watch Eraserhead, the exceptionally out-there first feature of David Lynch’s, which is in turn how it came to pass that Mel Brooks’ company went on to produce Lynch’s next feature Elephant Man); but anyway Stuart told me that Mel was in the midst of shooting his own next feature, in the immediate wake of Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein and Silent Movie, which was going to be a send-up of Alfred Hitchcock, and would I like to come visit the set and maybe work up a piece, he’d vouch for me, which invitation in turn is how I got the editors at the Village Voice, at the time a nationally distributed operation, back in New York to greenlight a proposal by this otherwise completely unknown LA writer. I hadn’t revisited that piece in years, but I dug it out of my files, and thought you might enjoy it as well. I cringe a bit at the lead, which does go on and on in its drop-jawed description of the workings of the on-site set that day (I hope that in the meantime I’ve learned to rein in such descriptions a bit), but if you bear with things, I think the pace does pick up, and the interview itself still feels quite revealing. (It’s worth remembering that around the same time, Woody Allen, who’d started out a bit awkwardly was really hitting his stride, with Annie Hall and Manhattan, while Brooks, who’d started out with a legendary masterpiece, The Producers, seemed to be settling into a sort of rut of spoof after spoof after spoof, and I wasn’t the only one, I think, who was curious what was going on with that.) Anyway, make what you will of what follows, and we can meet up again on the far side.

*

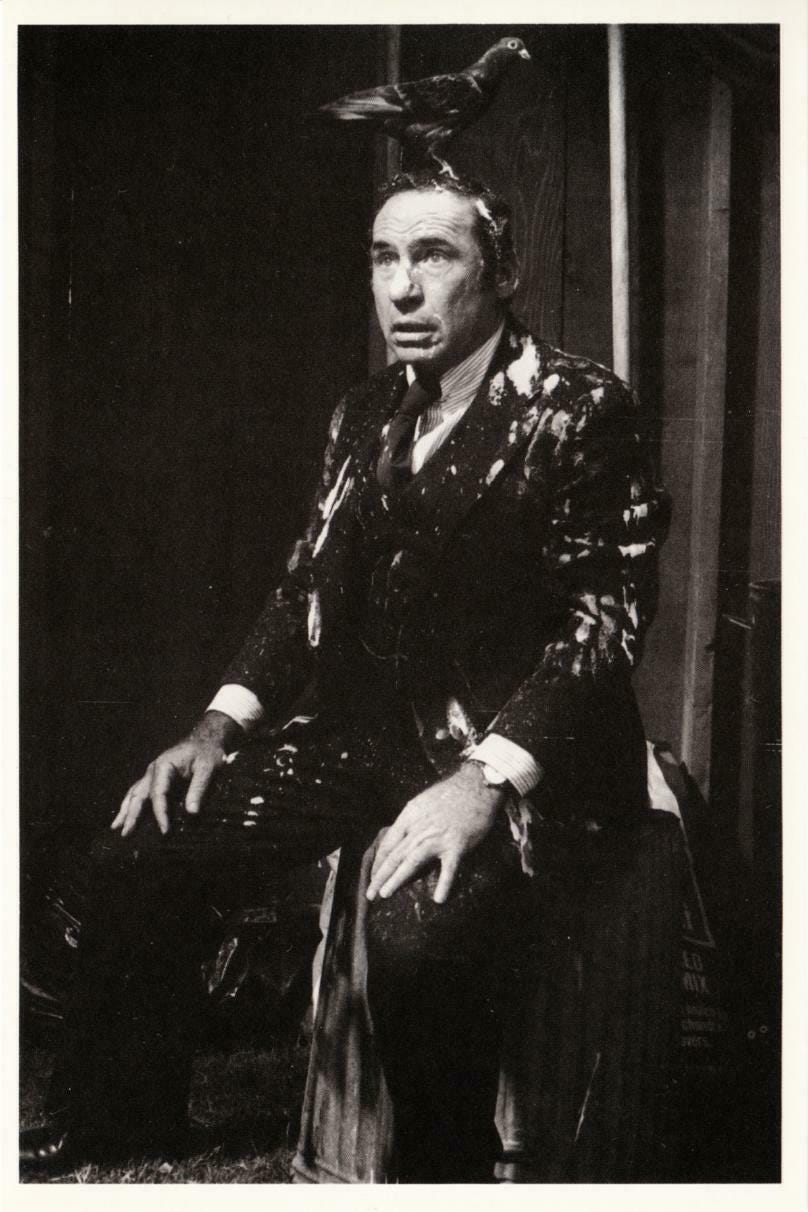

In a shady, semi-deserted park on the periphery of Pasadena's Rose Bowl, an incredible amount of technology has been brought to bear on a small, half-dismantled gardener's shed. The roof and one wall have been removed: Three arc lamps bleach the rickety remains in an even illumination. Just above, two chunky men sit, poised like grim archangels, peering out from their crane perches, their arms cradling two curious pneumatic drills. The camera—a dazzlement of lenses, meters, cones, and knobs—is wedged in tight; a half-dozen technicians sidle in and out, calibrating the exposure, adjusting the microphones, repositioning an upturned garbage can. Cramped against one corner, a crusty old man leans casually atop a ladder, nursing a pipe in one hand, palming a docile and somewhat confused pigeon in the other. Twenty yards to the side, the director, Mel Brooks, calls out: "Okay, let's go, boys. The joke's over, roll it. Action!" Suddenly the actor, Mel Brooks, barrels into the shed, yanks open the door, and collapses onto the upturned garbage can. He sighs with relief, and suddenly the pneumatic crappers begin blurting out their goosome mixture, each plop preceded by a muffled belch. Brooks looks up in dismay, receives a ripe one right on the noggin, and slouches back in resigned despair. The man on the ladder releases the pigeon, which spirals down, alights on Brooks's skull, and unfurls its tail feathers over his forehead. Two beats, silence, and Brooks sighs, "Cut."

You need only be informed that in this, his current film, High Anxiety (which opens this week), Brooks is sending up Alfred Hitchcock, and you will instantly surmise that here, on the last day of the 54-day shoot, he is trying to bury The Birds once and for all. Hitchcock's protagonists suddenly found themselves prey to a storm of man-pecking birds. In Brooks's version, the psychiatrist-protagonist—"a reincarnation of the classic Hitchcockian hero, the tall, handsome innocent who gradually becomes ensnared in a nefarious plot breaking out all about him," played by Himself—is relaxing on a park bench one afternoon as gradually, one by one, a flock of pigeons convenes on a nearby jungle gym. Gradually, one by one, the birds take off, swoop in low, and strafe. Slowly, calmly, Brookes assesses the situation, rises, begins to walk away, nonchalantly quickens his pace—the birds, in droves now, continue the pursuit—and, finally, breaks into headlong flight, seeking refuge at last in the ill-fated gardener's shed. High Anxiety may not be the first time Brooks has stooled to conquer, but in this scene, he offers one of the most outrageous examples yet of his distinctive mise en merde directorial style.

In the general public imagination, Mel Brooks is perceived as something of a madcap maniac, an image Brooks resents but at the same time helps to foster. In reality, however, his filmmaking persona is anything but out of control. From screenwriting through directing and then editing, Brooks is in complete command of his medium, utterly considered in his deployment of its resources. And the central preoccupation at every stage is vigilant attention to pacing and nuance. In this context, it is not surprising to learn that he first forged into show business as a drummer, snaring out summers in the Catskills. For Brooks, the process of creating a film is entirely one of orchestration. He has an uncanny sense of what will make an audience laugh, and how long and in what manner it will make them laugh. His directing metaphors are often musical: He inserts rests, changes key, quickens tempo, measures out the beat. He directs with an eye to editing, acutely aware of the jokes on either side of the one he is at that moment positing. And the entire process, for all its lunatic jangles, is intensely cerebral.

The crew repositions the lights, booms, and camera for the next phase of shooting—the long tracking shot of the headlong flight toward the shed—while Brooks banters with the journalists who have gathered for the last day of production. He is a master of the media-courting rituals, for he is directing not only the picture but also its eventual release and promotion, and is at all times cognizant of the central issue at hand ("I don't care what you write about me, so long as you make sure you write it in your December issue, in time for the premiere"). At one point, Kenneth Tynan arrives on the set to gather material for an upcoming New Yorker profile of Brooks. He and Brooks enjoy several minutes of casual badinage, but the December issue inevitably arises. "I've already looked into that," replies Tynan. "I spoke with my editor in New York about it last night and communicated your requirements in this regard, and he advised me that in that case the profile will either be set forward or pushed back by several months, precisely to avoid an unseemly coincidence with your premiere, because, as he put it, 'It is the policy of The New Yorker to avoid topicality at all costs.'"

By now the camera is on the tracks, the pneumatic gargoyles dangle in a metal basket at the far end of a sprawling industrial crane, and hundreds of pigeons are temporarily caged in animal trainer Ray Burwick's truck at the head of the improvised concourse. After distributing his instructions, Mel prepares for his jaunt. On the command "Action!" he begins to walk, slowly at first, but with a growing sense of panic, until he is in full flight. The crap-crane slices through the air 20 feet above him, its occupants richly dousing his path.

The birds are released and at first scatter skittishly, but Burwick's clacker at the far end of the field soon has them winging precipitously toward the empty cages over there. Brooks arrives in the middle of their swarm—"Cut!"—and jogs directly over to the video monitor. He and his three co-writers, Ron Clark, Barry Levinson, and Rudy De Lucia, review the scene and decide on a few more takes. The recaged birds are in turn doused with birdseed. Burwick, who also trained all of Hitchcock's birds, dryly remarks that the buckets of birdseed are actually extracted from horse manure. Brooks turns to his crew and shouts, "Hear that? I don't want to hear any more complaints about wages: These birds are happily working for horseshit!"

High Anxiety is clearly Brooks's most ambitious film effort to date. Aside from co-writing the script, directing and starring in the picture, and supervising its editing, Brooks composed the title song. Granted, in all these areas, he's had prior experience. But this is the first time he himself is also producing his own film. In addition, he is now personally supervising the film's publicity and distribution. Yet High Anxiety displays more than mere technical virtuosity on Brooks's part. As an homage to Alfred Hitchcock, he has had to fashion a film that works simultaneously as a comedy and a suspense thriller, the two elements playing against each other. The stratification of jokes is much more complex than in his earlier efforts, ranging from straight shtick to subtle allusion and on out to blatant parody. The plot and the characters are more boldly drawn and clearly articulated: He is eliciting a wider range of performances form his repertory company of actors.

The story line, of course, is simply essence of Hitchcock. Brooks himself is cast as Dr. Richard H. Thorndyke, an innocent whose world turns inexorably treacherous when he assumes command of his new post as director of the Psycho-Neurotic Institute for the Very, Very Nervous ("the PNIVVY"). He has unwittingly become an obstacle to the nefarious schemings of his head nurse, the vile-mouthed, vaguely mustachioed Charlotte Diesel (Cloris Leachman) and her sidekick, Dr. Charles Montague (played with lascivious subservience by Harvey Korman). The Tippi Hedren role goes to Madeleine Kahn, who, as the loyal, searching daughter of a millionaire industrialist imprisoned by the sinister pair, plays out her scenes with a delicate lilt of randy prurience. There is the usual Brooksian mixture of slapstick, snidery, double entendre, and character biz. But what makes High Anxiety special is its homage to the cinematic style of the master. We know we are in Hitchcock's universe, or why else would our point of view be scrunched below a glass table, looking up at the huge knees and dwarfed faces of the two archvillains as they conspire to commit yet another murder? Hitchcock fans will probably be most titillated by the sidelong tributes to specific films, for the plot, while contained in itself, is continually surfacing, like some lost stray submarine, in the middle of some other classic Hitchcock movie. The comic impact derives from the shudder of recognition as the Brooks film momentarily tumbles into the Hitchcock, and just as quickly, picks itself up, scrapes off the birdshit, and moves on.

In many ways, High Anxiety may stand, as Brooks insists it does, as his most accomplished film to date. Nevertheless, as I watch the crew beginning to break for lunch, I find myself harboring a grudging reluctance to throw myself wholeheartedly into the chorus of praise. This is partly because High Anxiety continues the string of Brooks parodies of other films. The Producers and, to a lesser extent, The Twelve Chairs, his first two films, seemed somehow extensions of a personal self.

Of course, neither of the films showed much box-office magic, even though The Producers continues to evince the remarkably long half-life of an established cult classic. But, starting with Blazing Saddles, and continuing with Young Frankenstein, Silent Movie, and now High Anxiety, Brooks has developed an almost formulaic approach: Unlike The Producers, which he wrote alone, these scripts are the products of television-style brainstorming sessions between shifting collections of comic writers. And they all work primarily as take-offs on earlier, cliché-ridden genres.

During the break for lunch, I mentioned my own misgivings about his continuing derivative style, how different his recent films seemed from The Producers.

"Well," he considered, "it's true that with The Producers there was a kind of inner reporting that I have not done for a while; most of the reporting since then has been external, my comments on my world and what we have come to expect as a movie. And that's something of an issue for me. I mean, I might like to get back to that earlier kind of thing, but I know that it's not going to reach as wide an audience. I really don't want to stop at every theatre in America called the Fine Arts. And that's what would happen if I went back to—I'm afraid that would happen."

Clearly there was an audience out there for his inner stuff, also. Perhaps not as large but certainly as devoted.

"But I'm worried about not-as-large."

Why?

"I'm General Grant" Brooks smiled. "General Grant said the generals he liked were not the generals who sat down and celebrated their victory, but those who took advantage of their victory and made another one quickly. Now, I can take advantage of my victories. I can! The field is open to me."

But after a while he would have won the war already and he could sit back—couldn’t he—and just do what he wanted to do?

"But that's a big decision. When does one win the war?"

I turned the question back on him: What would the battlefield look like to you when the war has been won?

"Comedy would have to be recognized as an important art form, by the world, by the Academy. A comedy would have to do as well as Star Wars one day for us to win the war. That would be total victory, I think. Then we could relax. It's not the money; it's the popular—as well as the industry's—respect for our art form. Comedy in its time is always thought of as frivolous. After you die, then they discover you were an artist. They gave Charlie Chaplin a special Academy Award for just surviving. They never gave it to him for The Gold Rush. No. We have to smash the . . . Our stuff has got to be respected, got to be popular, glamorous as the biggest picture. That would be winning the war."

What is it about pleasing everybody that was so important to him? A lot of directors aren't concerned with that.

"Oh, directors are different from . . . I'm really a combination—I'm a performer, too, so I guess the performer wants the biggest applause from the biggest audience."

Could he be satisfied with a louder applause from a smaller audience?

"That's a very good point. No, I wouldn't. I want a bigger audience and a bigger applause."

Where does that come from?

"It comes from being the baby of the family, how do I know . . .? I don't know. In analysis many things came out: It comes from being short; it comes from trying to please the father who I never knew because he died when I was just two-and-a-half; it comes from having all that love and attention heaped on me as a child, still needing . . . It comes from various things: I can't trace them all accurately.

"But," he continued, "I do want everybody to see the film. I want the old ladies at the afternoon museum series, the students in Westwood, the teenagers necking at the drive-in. I want the farmer off his tractor in Iowa. I want 'em all. And I include something for everyone. For instance, in this film, there's an elaborately silly bondage scene with Cloris as Nurse Diesel giving it to Harvey Korman, who's all strung up in chains. That scene is just going to dud in the smart houses on the East Side. But in the 1400-seaters in Des Moines, that scene will make the movie. I guarantee it: That will be the one they talk about."

He often mentioned Des Moines in this context. Had he ever been to Des Moines? What exactly was Des Moines to him?

"I know that if I don't do well in Des Moines, that my picture is only going to gross eight million worldwide. If I do well in Des Moines, it can go to 40 million."

Did he mean specifically Des Moines?

"Well, I do check Des Moines out and it does well for me. Because it's John Wayne country. It means that if there's a little town that only has three or four theatres, my picture will be booked into one of those theatres. You know how many hundreds of pictures are not booked into those theatres? They can only play 25 large cities in America, and that's the extent of it."

Who is the person in Des Moines who goes to see his films?

"Larry, I think his name is, Larry Gordon and his family. They go about 28 times. He's whoever goes to the movies in Des Moines. Whoever goes to movies in Des Moines will see John Wayne's film and my film, and maybe not Woody's, and maybe not Paul Mazursky's. And when you talk to me about a private film, I often say, 'Should I consciously lose Des Moines?’ Or maybe I can even be a greater artist than I think and get Des Moines and still say, ‘Yes, there are wild strawberries, yes, Umberto D. as a musical will work in Des Moines.' "

He idled for a moment, took a swig of coffee. "But that's a big question you're asking. I've made enough money: I don't really need the money. Money to me is just an idea. I worry a lot about how much my films gross, but only because that's an indication that they're watching, that I'm being paid attention to. I'm not interested in money. I don't need it. I mean, what does one need? To me, you need a Rolls or two, or a Rolls and a Bentley, maybe a 110-foot yacht, a four-motored jet, fantastic girlfriends . . . What do you need? I don't need much more than that. My only indulgence, really, is that I may spend more money than most people do on good wine. But even then, I'm careful to buy it by the case, on sale. But nowhere else: certainly not in my dress. My automobiles are very modest. My home is fairly normal."

He talked about wondering whether he should consciously forget Des Moines. But wasn’t it perhaps the other way around, that he was constantly bending his movies toward Des Moines rather than making the movie he might otherwise make?

"That's a good question, and the answer is no. I could never bend a movie. Once the basic vision has been born and is full blown in my mind, I might characterize some nuances so that they didn't get out of hand and get too personal or insular or not accessible to Des Moines, but the basic thrust of the picture would have to be something that I could accomplish with a great big bang. It must be accomplished, the target must be hit in the center, there must be a great big explosion—but it must be something that I think is in my personal domain. I've got to be the purveyor of something unique. That's where I keep the artistic aspects of my work in check."

We found ourselves talking about books (I fancy a Brooks adaptation of Gogol), and he spoke of the crucial years when he discovered the great classics of world literature, especially the Russians and the French of the 19th century. These were the years of his early twenties when his phenomenal success as a writer for Sid Caesar's Show of Shows almost brought him to the edge of despair.

"But in books I found a whole new world," he recalled. "Between psychoanalysis and literature, I decided to live. Seriously, I mean, I was seriously thinking of . . . There was no purpose and I could not get any profound satisfaction anywhere because I was too busy with my own inverted vanity and grief. So that helped a lot. Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Stendahl . . . they all helped.

"You know," he mused, "Stendhal wasn't very popular. I think he wrote in the preface to The Red and the Black or one of his books, 'This is 1839. A hundred years from today, I will be a famous author. They will understand me, and they will know how good a book this is.'"

But wasn't that precisely the point, that there is a kind of quality and value that isn't necessarily reflected in the immediate applause, and that therefore . . .

"Yeah, but how do you know that when you're dead? How do you know that they like you? If that's what you want . . ."

Stendahl knew it.

"Yeah, that's true, but I think he didn't know it. He was guessing. He was hoping."

And Mel has to know?

"Yeah, I'd like to know. I do like to know it. But there's no doubt about it: We have to risk some ideas that, going in, might not be knowingly acceptable to the masses."

In the meantime, I persisted, hadn’t it gotten to the point where the genre parodies he was doing now had gotten so formulaic that it was just stuff he could almost just do—

"No! No stuff can I almost just do, no stuff," he interrupted emphatically. "Every stuff is hard. If I could just do it, somebody else could just do it, too. We're not so different from one another. A nose between two eyes. Most people are alike—in their kidneys and in their thinking. The difference between me and other people is that I work very hard at my craft."

I asked him if he had been contemplating any ideas for his next movie. "I don't know," he replied. "I have to have an inspiration that grabs me and wrestles me to the ground; then I'll write it. Right now I'm toying with two ideas: one is a major musical, a Buzz Berkeley treatment of something you would do in 1978. The other idea is a very simple genre film: a bomber crew, World War II, England, missions, love, death, escape . . ."

Speaking of which, he was already up and walking back toward the set. Loping along behind, I asked him about the heavy work pace, whether now that he was winding up the shoot he was looking forward to a long vacation. "Well," he replied, as he zeroed in on the camera placement, "vacations are okay, but after two weeks you realize you're never going to beat the court pro, so, what's the use? I'd rather be back here, doing something where I know I can be the best."

Arriving at the camera, he paused and turned toward me. "I don't want to sound immodest, but I am. I couldn't do what I'm doing without ego, without vanity. I mean, I really think I'm hot shit, or I couldn't do it; I just couldn't modestly or obliquely enter this field. You have to step into it; you cannot quietly segue into being a personality in our business without pronouncing yourself, sometimes rudely; and that's even more the case in comedy, which is highly competitive. It's a loud business: You've got to be very loud. I mean, I learned that back when I was one of the kittens in the Show of Shows litter and we were all mewing and looking for our teat, you know. If you didn't find your teat you died, so it was a fight for survival. And Sid Caesar's ear was hard to get to with seven other comedy writers around. I had to fight my way through guys like Neil Simon and Woody Allen and Larry Gelbart—and I did, I did! The point was not only to survive—that's a modest word—but to gain the victory! And it's still the same today."

I asked him if there was a quiet Mel beyond all the clamor and commotion. "Yes," he conceded, "there is a quiet person inside of me, and he's just appalled at the other person raging and rampaging around, doesn't understand how anybody could be so grotesque, loud, and vulgar, and why anybody would be his friend or be a fan even for one moment to such a disgusting person. But we'll have to talk to Robert Louis Stevenson about this problem: I think he did a good job in Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde." Brooks broke into a grin.

He returned to the filmwork: All that remained were a few coverage shots, some close-ups of crazed birds, and a few last point-of-view angles. He dispatched these with typical verve and efficiency. I veered off to the side and crouched in the shade of a large tree, aware of being in the presence of an unusually engaging, clever, and kind fellow. I would have liked to have told him so. But that impression would not have been enough for Brooks: He requires superlatives or he feels bereft. The result is a certain giddiness on the set, people laughing too hard at throwaways, for instance; either that, or a stubborn resistance to even give credit where credit is due.

The core attribute of Mel Brooks is a sort of hypersensitivity to the outside world. On the one hand, this is reflected in an almost naive celebration, an unmediated delight in the sheer richness of the everyday lifeworld, the human provenance. Here is the source of his richest comedic material, in his extraordinary attention to nuance and detail. But this hypersensitivity is also the source of his continuous anxiety as to his standing in the estimation of others. It's as if he moved through the world without a skin. And that anxiety, in turn, skews the artistic production: Trying to please the largest possible audience, he confects another genre parody rather than hazarding a more personal statement. Or within any given film, some small, delicate insight is blasted home, rendered utterly blatant, so that there's no doubt that everyone will get it.

My thoughts drifted to Brooks's extraordinary propensity for metaphors of combat whenever he's discussing his cinematic intentions. The dovetailing between the languages of comedy and violence is by now proverbial: Jokes die; monologues bomb; when successful, comics kill their audiences. But his language is especially charged, and the confrontation seems somehow more personally intense. In a curious sort of way, the audience is forever the potential enemy: At any moment, it could break out in apathy. This danger has to be smashed. The point is not merely to survive but to gain the victory. The explosion he plots is the audience's uncontainable laughter. He triumphs when, momentarily, he utterly disarms his would-be adversaries. His expansive generosity arises simultaneously with his tenacious defensiveness. Perhaps a similar process is at work in the self-exposure of other comedians, but with Brooks its operations are more transparent, and, one imagines, more intense. His comedies only hint at the drama of their creation.

*

And there you have it. Did you notice how the Village Voice published the piece on December 26, 1977, exactly as Mel had wanted. (Tynan’s piece didn’t appear in The New Yorker until October 22 of the following year, at which point, clearly annoyed at having been featured in that bit part in my piece, he was able to enact a whiff of sweet revenge by casting me as a somewhat bumbling unnamed student asking gawky, but narratively useful, questions over lunch in his. You can also find the piece in his Show People collection.) Pauline Kael for her part in her relatively scathing review of the Brooks film in the New Yorker the week immediately after the release of mine (January 1, 1978) keyed many of her comments off of those Des Moines characterizations of Mel’s “in a recent interview in the Village Voice”—a passing citation which constituted one of the high points of my life up to that moment (you can sample the passage in question here or else gawp at the whole review {pp. 371-376!} in her When The Lights Go Down collection—god could that woman write!).

But Mel seemed to like my piece, he thought it had offered a fair representation of his thinking and process, and indeed he subsequently asked me to write the liner notes for his Mel Brooks’s Greatest Hits LP album a few months later—surely one of the odder entries in my own CV, though you can procure the LP and even peruse said liner notes here. And I continued enjoying my subsequent visits with Mel whenever I called on my old pal Stuart Cornfeld, until Stu went on to helm Ben Stiller’s production company where he was responsible for such marvels as Zoolander and Tropic of Thunder. Stu passed on, ridiculously early, a few years back, a loss I cited at some length in the acknowledgments section of my recent Trove of Zohars book and which I still can’t quite get over.

But Mel lives on, as vivid as ever. (Strange indeed the way his and Woody Allen’s respective subsequent careers seemed to flip valences.) As it happens, I heard about his 98th birthday by way of a reference in my Australian cousin Nic Gruen’s splendid aggregator substack the other day where he celebrated by linking to a wonderful scene from a British TV show from 1983 in which Mel prevailed upon his wife Anne Bancroft (god did he love that woman!) in the audience to join him onstage for a rendition of “Sweet Georgia Brown”—in Polish!

That in turn guided me back to the opening of their 1983 remake of the Jack Benny/Carole Lombard/Ernst Lubitsch 1942 film To Be or Not to Be, a black comedy about a troupe of actors in wartime Poland who deploy their skills at disguise to foil their Nazi occupiers, based on a story of Melchior Lengyel (who as it happens was the émigré Hungarian playwright who supplied the libretto for my composer grandfather Ernst Toch’s final Scheherazade opera). That Brooks To Be or Not to Be was a real return to form on Mel’s part as far as I was concerned, to the personal form, that is, of The Producers, as of course was his subsequent restaging of that very first film of his as a smash hit Broadway musical in 2001. (Talk about the latter-day resurrection of first efforts!)

Anyway, Mel, as they say in Poland, Sto Lat!—may you live one hundred years! And more.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.