January 30, 2025 : Wondercab Mini (84A)

MORE MARTA!

Last week’s Cabinet, with its profile of the Los Angeles Weimar émigré grand dame Marta Feuchtwanger, in her mid-eighties back in 1975 when I engaged her in a months-long oral history on behalf of UCLA and USC (the transcript of which in turn ran to four volumes and almost 2000 pages), seemed to go over quite well with readers, several of whom wrote in asking for more—and indeed revisiting the online version of the transcript itself once again over the past few weeks has had me finding all sorts of fresh passages I’m eager to share. As I said last week and have been marveling at all over again ever since, she was as sharp as ever during those sessions, insightful and funny and spry (albeit occasionally almost surrealistic in her non-sequatauristic leaps) as she conjured into being the four separate lives she seemed to have shared with her husband, the eminent and prodigiously bestselling German historical novelist Lion Feuchtwanger, in the teens and early twenties in Munich, the late twenties and early thirties in Berlin, the late thirties and early forties in their first exile in Sanary on the French Riviera, and then, following a hair-raising last-minute escape in 1940, in their second exile in Pacific Palisades at the heart of that astonishing ingathering of cultural luminaries initially in flight from Hitler.

Last week I shared a section of the oral history in which Marta described her heroic efforts aimed at saving the couple’s magnificent rare book collection during the 1961 Bel Air Fire. This time, I thought I’d highlight a few other characteristic passages from earlier in the saga. Note that while the oral history as a whole is filled with sober consideration of substantive subjects of themes, I've weighted this particular selection toward the more wry and antic, notes that were continually bubbling just under the surface as Marta unfurled the arc of her astonishing life.

*

THE JEWS OF MUNICH, THEIR FELLOW BAVARIANS, AND THEIR RESPECTIVE ATTITUDES TOWARD THE NATIONAL DRINK

Like her eventual husband Lion, Marta was born into a Jewish family, though his was both richer and more Orthodox. Still, like most of their coreligionists there in Munich, the two of them were profoundly assimilated into German culture, or at any rate imagined themselves to be, in the years before the First World War.

WESCHLER: About the Jews of Munich: would they have seen themselves every bit as much aligned to the royal family of Bavaria?

FEUCHTWANGER: Yes, absolutely yes. The Jews didn't feel Jewish. They did feel Bavarian. They were Bavarians. They liked their beer and they liked their Radi. They liked their Gemuchtlichkeit, if you know that, the wine and the beer cellar. That was where Hitler later made his big speeches. And when there was a new brew, in spring, the Salvator beer, which was an extra strong beer.... The Jews never got drunk, like the others, but they liked to drink. I never saw a Jewish drunk in Munich. Or in Germany, by the way. But you could see many drunk Bavarians.

The same at night on the streets around. They were very, very—sometimes very ferocious. I didn't want to meet one on the street, you know. They didn't know what they were doing. The first time I was afraid was when I met a drunk. They had the knife always very loose. At the villages, every Sunday there was a big fight in the village inn. There was a playwright in Austria named [Ludwig] Anzengruber—he makes one scene like that; one man threw a chair into the lamp; it was filled with petroleum, oil. So it was dark, and nobody knew whom he was fighting or battling with. The morning, when it was light again, they had to look for the noses and ears which were lying around. Then there was always a doctor who could sew them on. They only had to be careful that they didn't sew the wrong nose or the wrong ear. It was like your baseball, you know.

*

HIKING THROUGH THE HILLS SOUTH OF NAPLES, 1913

Soon after their wedding (when Marta was barely twenty), she and Lion embarked on a more-than-two-year vagobonding trek through France and Italy and North Africa that would only get interrupted by the onset of the war in 1914. Here we find them hiking through the back-country hills south of Naples:

It was a long time until we found something to eat, a village or so, but there was a funny thing: when you saw a shepherd with black porks, very little porks, in big masses—it was just full of those little black porks—then you knew that you would find some chestnuts, because the only food for those little porks were chestnuts. So we followed the flock of the little porks and we found some chestnuts, which we ate, and then we found some berries, and it was all very nourishing. [laughter]

Then finally we came to a village. It was a very simple inn, and we were glad to wash ourselves and sleep in a bed again. Then the waiter came and said, "There is a man outside who wants to speak with you." My husband thought he wants to sell us some souvenirs or something. He said, "We don't buy souvenirs." But the waiter said, "Oh no, he's a riccone"—that means a very rich man. So my husband let him in. He came with handfuls of gold, threw them over the table,

and said, "I want to buy your wife."

*

IN MUNICH

DURING THE BAVARIAN SOVIET REPUBLIC, 1919

In the chaos after the War, Bavaria experienced a quite radical (though short-lived) political upheaval, and Lion and Marta were friends with many of the main protagonists.

WESCHLER: "Okay. You also have a story about you yourself needing a pass.

FEUCHTWANGER: Oh, yes, that was a little later. But during the revolution, there was another thing: There was a man [Ernst von Bassermann] who was a cousin of the famous actor [Albert] Bassermann who came here because he couldn't stand the Nazis (even though he was not Jewish and it wasn't necessary for him to leave Germany). And this actor’s cousin was a professor of philosophy and very rich and had a beautiful palace in the suburbs of Munich. He was very smitten with me—I don't know why. I think I looked so sinful. He was very pious, and this always attracted the pious people. I often noticed that in the countryside, the pastor and the priest always wanted to speak with me. For them I was just a kind of symbol of sin. [laughter] He was at every first night in the theater where we also were, and we always spoke with each other. He was an enormous man, and he was a widower. I think I was the only woman who played any role in his life after the death of his wife. So he invited us very often to dinner. He had a very wonderful cook, a male cook, and also the most beautiful wines, because he himself had vineyards on the Rhine. He invited us also after the revolution, and he said, "You know, I was very much afraid...."

(He was a collector of watches, watches and clocks, the most famous collection in those times of watches and clocks: old watches which looked like eggs, and another clock which was even eerie. When you went in, he had it hanging in a rather dark room. And on the pendulum, there was one eye; it was going from one side to the other. It was very eerie, because you always felt the eye is watching you or following you. It was beautiful. He liked always to bring me in this room because I found this so exciting. [laughter] It was called "The Eye of God," this clock. That's the name. It was a famous name.) So during the revolution he invited us and said, "You know, I was very much afraid that they would ravage my house and plunder it and maybe even destroy things. And they came also to my house because they went to all those villas of rich people. But they just asked for money and if they could get something to eat. Then they left. I gave them some wine," he said, "and then they left." He was so astonished that he wasn't killed and not everything was destroyed.

WESCHLER: What was his name?

FEUCHTWANGER: Von Bassermann-Jordan. He was a nobleman. And Bassermann was the famous actor.

WESCHLER: I see. Well, you still have to tell the story about the pass.

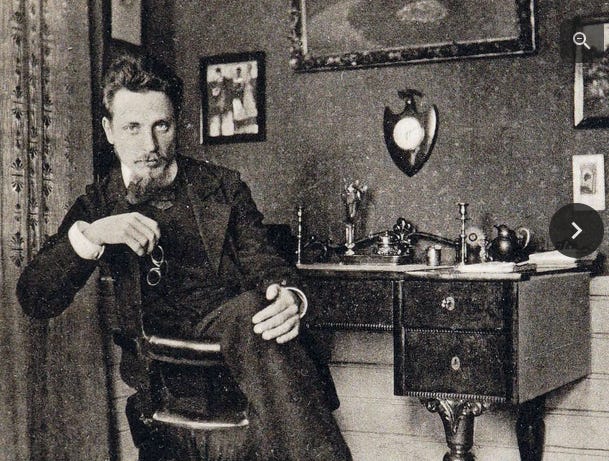

FEUCHTWANGER: And the other story. Did I tell the other story of Rilke?

WESCHLER: No.

FEUCHTWANGER: Our long-time friend Erich Mühsam was a kind of chief of police during the Räteregierung. He was also a very good friend of Rainier Maria Rilke and a great admirer of him, and he was…Even when they always preached not to plunder, there could happen something: soldiers could drink or so. So he sent one of his soldiers to the apartment where Rainier Maria Rilke lived, and put a sign on his door, where it says, "It's not allowed to plunder in the house of Rainer Maria Rilke." And nobody plundered. You know, that's the way they made revolution in Munich.

WESCHLER: This was a revolution with class.

FEUCHTWANGER: Ja, ja. [laughter]

WESCHLER: You still have to tell the story of the pass.

FEUCHTWANGER: Ja, that was also during the Räteregierung. There was curfew, and nobody was allowed to be on the street after eight o'clock—also to avoid murder or whatever, you know, rape. But we were invited by a man who was a black marketeer. We were always so hungry we would have even accepted an invitation from the Mafia. So we went there with a little bit of a bad conscience, because he made his money first in the war, as a war profiteer, and then he was a revolution profiteer. Still, we went there. And this night he also invited us again, and we couldn't go out. So my husband went to the Wittelsbach Palais, the same office where our friend Bruno Frank before was, and asked for a pass. Then he got a written document, a little piece of paper where it said, "Possessor of this has the right for free intercourse, signed, the Cheese Distribution."

WESCHLER: A very handy thing to have.FEUCHTWANGER: Ja, we were very glad, and it helped. We were stopped. We had a taxi to go to this man, and we were stopped. And then my husband showed the soldier this pass, and then it was just right.

WESCHLER: What was the German word for "free intercourse"?

FEUCHTWANGER: It was "das Recht auf freien Verkehr," [which] means free movement; but it also meant the same thing, you know. [laughter] But it wasn't meant like that: it just came out. They didn't know better German. They were simple people.

WESCHLER: Well, what do you expect? They were just the Cheese Department.

FEUCHTWANGER: Ja, that was signed "the Cheese Department." And those were workmen or so who gave those out.

*

HELL ON WHEELS:

LION LEARNING TO DRIVE IN BERLIN

FEUCHTWANGER: In the days when Lion was learning to drive, we made some excursions sometimes, little trips in the neighborhood, the little lakes around Berlin, which has a very beautiful environment. Once we came [to a section where] it was not difficult to drive, so I told my husband, "Now you drive a little bit." So he drove, and all of a sudden we came to a factory. It was the end of the day, and all the factory, all the laborers and the girls came out. We were just surrounded by people, and my husband didn't know what to do. I took with my two hands the driving wheel and wanted to drive it to the curb, you know, because I knew my husband wouldn't stop. So I drove it to the curb, and then a policeman came and said, "Who of you has a driver's license?" So we both showed him our driver's licenses, so he couldn't say anything. He said, "I saw the lady doing something on the wheel. That's not right." But we both had our driving license. Then I said to the policeman, "I think I drive now myself." So we left this place.

But later, on our way back, when my husband was again on the wheel, there came some cows across the street, so my husband went straight into the cow. [laughter] She turned around—of course, he didn't give much gas so the car stopped anyway; he killed the engine. And the cow just looked around with big eyes, very sad. But then I...

WESCHLER: You had actually hit the cow?FEUCHTWANGER: Ja, but nothing happened, not even the fender, because he already...

WESCHLER: I'm not worried about your car, I'm worried about the cow!

FEUCHTWANGER: The cow just turned around and looked with very sad eyes at my husband. [laughter] You could say "reproaching" but maybe that's too much for a cow. [laughter]

*

ALMOST LOSING RAPPORT

WESCHLER: You were going to tell me more about that New Year's party at Lion's publisher Ullstein's in Berlin.

FEUTCHTWANGER: Ja. That was when Remarque was at our table, and also the director of literature at the Ullstein's, Dr. Emil Hertz, who was our neighbor in Berlin. He was the one who came through the woods between our two properties—I think I told you—to make the contract. He was a tall, big man, and we thought... We all liked to drink, and mostly Remarque. I never drank at home, but when I was with other people, I drank with them. So Remarque said to me, "Now we drink Dr. Hertz under the table." So we drank and said, "To your health." [Every] time, you know, he had to drink and we drank—he drank every glass which we drank—and finally Remarque and I were under the table and he was still sober. [laughter] And I had to drive home.

WESCHLER: Well, judging from the stories you told me about your driving, you were probably driving better drunk than if you weren't. [silence, two beats]

But what was Remarque like?

FEUCHTWANGER: Remarque was very elegant. He was very much an homme à femmes: the ladies liked him; he liked the ladies.

He always wanted—because he saw that I was interested in autos and in car driving—that I go with him to Italy on his Lancia. He had just bought a new Lancia, which was the fastest car in those days. But I didn't go with him in this or my other car. [laughter]

WESCHLER: That doesn't surprise me, for some reason.

FEUCHTWANTER: It surprised me. [laughter]

* * *

And so forth. You get the idea. Like I say, it’s all available online and I thoroughly commend it to your attention. In particular, you might like to take a look at Marta’s riveting account of the summer and fall of 1940 and the couple’s harrowing escape out of occupied France, with the Nazis hot on Lion’s tail, which you can find in Volume Three, pages 979-1046.

* * *

See you next week!