WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This week, in the lee of those terrible LA fires, we delve into the Archive for a visit with Marta Feuchtwanger, German émigré dowager legend, who once fought her own Palisades fire.

* * *

The Main Event

FROM THE ARCHIVE

MARTA FEUCHTWANGER,

20TH-CENTURY WOMAN

I’d known Marta Feuchtwanger, the elegant widow of the distinguished German historical novelist Lion Feuchtwanger, the two of them having been major cultural figures successively in Munich in the teens and early twenties, Berlin in the late twenties and early thirties, in initial exile in Sanary on the French Riviera through the late thirties, and further exile in Pacific Palisades from then on—anyway I’d known Marta pretty much since my own childhood (she had been close friends with my German émigré grandparents) which is likely why the people at the UCLA Oral History Program, (where I was working in the mid-seventies after having graduated from college) chose me to go cull her story, which became a year-long project (because, what a story!), at the end of which I composed a profile of her exquisite eminence for the local alternative newsweekly, the LA Reader (in their issue of September 14, 1979), from which the following remembrance has been adapted and updated. Why Marta has been so very much on my mind lately (aside from the fact that she often is no matter what) will presently become evident.

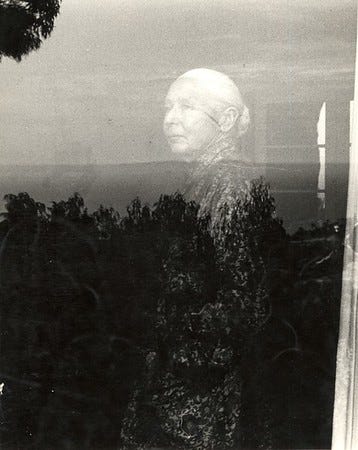

If you’d attended concerts, plays, consular receptions, university lectures, or any number of other public occasions in Los Angeles back in the day (that day being, oh, the mid-seventies), you'd almost certainly have seen her; and if you'd seen her, you'd no doubt have wondered who she was, this splendid octogenarian dowager, perennially wrapped in her long black Chinese gowns, her sleek white hair pulled back tight in a neat bun, her face a study in wry animation. Well, that would have been Marta Feuchtwanger, and a more vibrant woman you’d likely seldom have encountered.

Despite her years (born in 1891, she was eighty-four in the days I’m recalling here and would go on to live until 1987), Marta was a very busy woman. Just try to slip an appointment in edgewise as she’d reel off her commitments—this committee for the Watts Towers, that performance of an experimental theater company at the Fox Venice, this next visit from the Polish ambassador. Granted, she no longer trudged down the hill from her Pacific Palisades home each morning—every morning of the year—to bathe in the chilly waters of the Pacific (she gave that up a few years back: "Come on," she’d wink, "There are limits to what an eighty-four-year-old woman can do"). But you'd be hard-pressed to locate any other such limitations as she drove off virtually every evening, often ferrying friends a generation or two younger than she to various cultural and political events throughout the Southland. And during the days, she’d be devoting hours to her teeming desk, managing the literary estate of her late husband, the prolific German historical novelist Lion Feuchtwanger, or escorting rapt visitors through his extraordinary library which is equally much her legacy and which Marta had in the meantime willed to the University of Southern California. So pinning her down for an appointment was seldom easy.

Across the latter half of 1975, though, I’d had the good fortune of sliding several dozen meetings into Marta's frenetic calendar. As part of a joint undertaking by the UCLA Oral History Program and the USC Library, I’d been dispatched to record Mrs. Feuchtwanger's reminiscences on tape. The fifty hours of recorded conversation that resulted got distilled into four volumes of edited transcript (edited, that is, by me), almost 2,000 pages covering her friendships and interactions with many of the greatest figures of world politics and culture over the previous century, and by the late seventies, the utterly absorbing record was being made available for perusal by scholars and other interested parties at the libraries of both universities.

Throughout our conversations, Marta maintained a light, easily flowing tone. (We’d known each other since my childhood, she having been dear friends with my grandparents, Ernst and Lilly Toch, and we always seemed to get a kick out of each other.) She sometimes seemed as bright and sassy as the young woman whose life she was recounting. Although her English was entirely fluent, the transcripts are festooned with delicious literalisms, near-misses of translation (as when she describes hiking through Sicily and encountering "a small herd of porks"), and the tapes preserve her marvelously distinctive diction, in which, among other trademarks, the v's often flutter into w's (as when she tells you of "the clinching and wampish dress" she once wore during a particularly bawdy Munich Fasching).

Marta was born, as I say, in Munich in 1891 to middle-class assimilated Jewish parents, their only child to survive infancy. From out of an over-sheltered childhood, she blossomed into a lovely teenager, physically active and intellectually alert. In 1910 she met Lion Feuchtwanger, seven years her senior, a young playwright and critic, at a party given by one of his sisters. His parents, quite wealthy Orthodox Jews (the margarine barons of Munich), had virtually disowned their lapsed son, who had in the meantime taken to living a bohemian life, espousing l'art pour l'art, and cutting a dashing figure in Munich underground society. He was immediately taken with her.

Marta described the nervy tone of their early encounters, Lion's persistent siege, her own persistent stubbornness. But the chemistry of the relationship gradually took hold, and the two were soon pursuing "a secret courtship," two years of secret dalliances in Leon's attic apartment, secret, that is, "until it was no longer possible to keep them a secret." The session in which we covered this period was particularly coy, as interviewer and interviewee alike contrived to relate the entire process without once resorting to use of the word "pregnant." Marta deployed every conceivable euphemism, finally relating the events of her wedding day, during which she was gowned in black, "because I couldn't very well wear white in my condition."

Their marriage, conceived in secret, entered into out of necessity, would last forty-eight years, but it barely survived its first. Within a few months the young couple was in Lausanne with Marta delivering her child, a girl. Both mother and daughter, however, contracted puerperal fever; the child quickly died, and the mother almost followed. Marta recalled one night when she lapsed into a virtual coma. Two nurses were bathing her, "and one said to the other, 'This is the last night we will have to be here.' I heard that," she remembered, "and even though I couldn't speak anymore, still, in my mind I said, 'I don't think I will do that.'" And miraculously, Marta did recover. The Feuchtwangers would never have another child—there simply would not be time, Marta explains—but it is interesting that throughout his novels, Feuchtwanger is haunted by the elusive presence of daughters.

As Marta recovered, the two began a gypsy honeymoon, trekking from the French Riviera down the boot of Italy across to Sicily and eventually over to North Africa. For almost two years they lived out of their knapsack from day to day, utterly oblivious in their primitive happiness to the gloom that was inexorably gathering over Europe.

In August 1914, the young couple was sojourning in the desert of French Tunisia when they suddenly found themselves arrested as enemy aliens. Lion was incarcerated in a prison camp, and Marta, on the outside, worked frantically to wheedle his release. At length she succeeded, and the two quickly smuggled their way back to Munich, where Lion was summarily slapped into the Kaiser's army.

During the war years, Lion's aesthetics gradually changed: In short, he became politicized. Indeed, his "Lied der Gefallenen” (Song of the Fallen) in 1915 was among the first German antiwar poems. As the war savaged the monarchial social order in Bavaria, Lion and Marta became increasingly sympathetic to the socialist upwelling that, with the conclusion of hostilities in 1918, briefly saw the ascendancy of a radical leftist regime in Bavaria. That experiment was quickly quashed by the Berlin authorities, but Lion's and Marta's political sympathies would persist.

Much has been made of the extraordinary convergence of artistic genius in Berlin during the late twenties, but few people realize how seminal Munich was in earlier years. Indeed, for all intents and purposes, Munich can be seen as Berlin in preparation. It was here that Kandinsky and the Blue Rider movement invented pictorial abstraction, here that Bruno Walter secured his first major orchestral podium, that Max Reinhardt dazzled summer theater audiences, and that Thomas Mann and his brother Heinrich vied for literary supremacy.

As Marta unfurls stories of Munich at the time, she displays a sly sense of narrative, often withholding identities for the punchline. One afternoon in 1919, for example, as Marta tells it, Lion, who was by then the town's ranking theater critic, was approached by a brash twenty-year-old medical student from the provinces who thrust upon him a sheaf of pages, his fledgling dramatic effort. Feuchtwanger was impressed and championed the work into production. The boy's name was Bertolt Brecht. (The two would remain lifelong friends and even collaborate on three plays.)

About the same time, Marta continues, some of their friends in the interim socialist government were manning the food-rationing office when they were visited by the papal nuncio, in full regalia, who meekly inquired whether under the new regime the church might still receive its allotted stamps for butter. This man was Eugenio Pacelli; in 1939 he would become Pope Pius XII. Indeed, it now seems as if much of the entire midcentury were in gestation there in the streets of Munich.

One afternoon in the public gardens, Marta and Lion were having tea. As on any other afternoon, the tables were crammed with diverse parties in animated conversation. The table next to theirs, for example, presided over by composer Hans Pfitzner, was embroiled in political disputations. As Lion rose to leave, a slight, silly-looking young man from that table solicitously hurried over to help him with his coat. This was Adolf Hitler.

A few years later, in 1923, Hitler's abortive (and premature) Beerhall Putsch signaled the closing of an era. Although Hitler had ludicrously failed this time around, the political climate in Munich quickly deteriorated, and most of the city's cultural elite were presently scampering for the safer high ground of cosmopolitan Berlin. Lion and Marta joined the exodus, but Lion also sounded an early alarm in his writings. His 1927 novel Success included the first sustained satirical treatment of Hitler in German literature; it was a portrait the Nazis would not soon forget.

The Feuchtwangers' Berlin years were lively. Feuchtwanger's reputation soared with the sensational successes of such novels as Jud Süss (based on the notorious antisemitic execution of an 18th century Court Jew in the small German duchy of Wurttemberg, subsequently transmogrified into a virulently antisemitic 1940 propaganda film by the Nazi director Veit Harlan, uncle incidentally of Stanley Kubrick’s eventual wife Christiane) and The Oppermanns (the epic of a Jewish family in Berlin at the edge of the coming abyss, itself subsequently made into a distinguished German television movie by the director Egon Monk in 1983, and trenchantly celebrated by columnist Pamela Paul in 2022 in a New York Times op-ed entitled “Ninety Years Ago, This Book Tried to Warn Us.”) They played host to cultural figures from throughout the world, ranging from Sinclair Lewis to Sergei Eisenstein. Lion plowed his substantial royalties back into a nascent bibliophilic obsession: By 1933, his was one of the finest private libraries in Berlin. It, and almost everything else, would be lost.

In January 1933, while Lion was on tour in America and Marta skiing in Austria, Hitler seized power in Berlin. The Feuchtwangers would never return to their ransacked home. Upon rejoining each other, they instead sought refuge in France, in Sanary, a tiny fishing village along the Riviera between Toulon and Marseilles that somehow became quite magnetized during this period. For seven years, their neighbors included Aldous Huxley, Walter Benjamin, Bertolt Brecht, the Mann brothers, Hans Frank, Ludwig Marcuse, Franz Werfel and Alma Mahler.

{On the quay wall, to the left: Egon Erwin Kisch and Marta Feuchtwanger; and to the right, Helene Weigel (?). Sitting in the front row, from the left: Walter Benjamin, Thomas Mann, Katia Mann, Heinrich Mann, Rene Schickele, Julius Maier-Graefe, Alma Mahler-Werfel, Franz Werfel. In the back row, from the left: Erwin Piscator, Bertolt Brecht, Arnold Zweig, Lion Feuchtwanger, Friedrich Wolf, Christiane Grautoff, Ernst Toller, Erika Mann, Nelly Man, Klaus Mann, Golo Mann, Hermann Kesten, and Joseph Roth.}

Lion worked feverishly, composing his greatest historical novels, the Josephus trilogy, while at the same time producing a string of contemporary stories spotlighting the German calamity. In the meantime he slowly built up a second library, almost as fine as the first, and equally doomed.

In 1940, with Franco-German relations deteriorating, the French government interned its Jewish exiles as potential enemy aliens. The Feuchtwangers, like all other Germans, were herded into camps. They were separated, with Lion incarcerated at Les Milles and then the St. Nicolas internment camp near Nîmes and Marta at Gurs in the foothills of the Pyrenees. In June, the Nazis swamped the French defenses and seized control of the camps, and Feuchtwanger was among a select group of individuals they were specifically seeking.

During a summer fraught with danger, Marta (age forty-nine) escaped out of her camp, wandered through Southern France, its roads swollen with disoriented and despairing refugees, and finally determined Lion's location. She secreted herself into his camp (disguised as a black marketeer), established contact, secreted herself back out, and then, with the assistance of a pair of freelancing American consular officials, engineered Lion’s kidnapping out of the camp. The Feuchtwangers then holed up in a Marseilles attic for several months before they were able (now with the help of Varian Fry, the legendary Quaker delegate of the non-governmental Emergency Rescue Committee and his Unitarian colleague, the Reverend Hastings Sharp) to hazard their perilous escape, by foot over the Pyrenees, by train through fascist Spain, and finally on two separate ships out of Lisbon. (Arriving in America, Lion quickly published his account of the desperate odyssey, The Devil in France: My Encounter with Him in the Summer of 1940.)

Within a year they had re-established themselves, this time on the California Riviera, eventually securing a dilapidated castle on Paseo Miramar in the hills of Pacific Palisades high above where Sunset Boulevard, after its twenty-four mile meander, finally reaches the sea—with a panoramic bay view to match. The Villa Aurora as it would come to be known.

They worked as best they could. Lion continued writing books and was quite successful; with the royalties he set about amassing his third library, perhaps his greatest. Marta threw herself into terracing the hillside and layering in an orchard garden that would become almost as celebrated as Lion’s library. And once again they found themselves in a rich community of émigrés. Almost the whole Sanary group had resurfaced on the West side of Los Angeles, and now they were joined by others, including Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Fritz Lang, Peter Lorre, Salka Viertel, Otto Klemperer, Bruno Walter, Max Reinhardt—the list is legion. (Indeed Lion and Marta were the ones who’d financed their old friend Brecht’s escape via Finland across Russia to Vladivostok across the Sea of Japan aboard a Swedish freighter traveling onward to Los Angeles harbor in late 1941, one of the last such ships to attempt the passage, and they were there at the harbor to meet him and take him back to the Villa Aurora,

subsequently helping him to secure a home in Santa Monica.) Many in the cohort found employment in local universities or Hollywood. They found succor in one another's company. They spent evenings on the Palisade, watching the sun set over the Pacific contemplating the ravages in the land they had left behind, awaiting the coming dawn. They were, as someone once called them, Exiles in Paradise. (Though as Brecht himself once noted, archly, in the first of his “Hollywood Elegies”: “The village of Hollywood was planned according to the notion // People in these parts have of heaven. The people // Here have come to the conclusion that God // Requiring a heaven and a hell, didn’t need to // Plan two establishments, but // just the one: heaven. It // Serves the unprosperous, unsuccessful // As hell.”)

Time passed. The war ended. Dawn came. But the eastern sky was bloody with revelations of concentration camps and bomb devastation. And the satisfactions of victory were further tempered by a pervading sense of anxiety as America lurched from its external war against fascism into an internal obsession with communism. The very broadcasts and papers with which these emigres had cried out against Nazism from its earliest festerings were now being cited against them as evidence of longstanding "communist" sympathies. The Feuchtwangers saw their friends Brecht and Hanns Eisler hounded out of the country and Thomas Mann leave in disgust. Feuchtwanger himself, despite the success of his novel Proud Destiny, a celebration of the American Revolution that he’d seen as a gift to his adopted land, was repeatedly denied citizenship on grounds—and this was the official charge—of "premature antifascism." (Ironically, Stalin was simultaneously banning his once-popular books in the Soviet Union on grounds that they were too reactionary.) A few days after Lion's death in 1958, at age seventy-four, Marta received a call from a functionary at the Immigration Service, grievously apologizing that they had just been about to grant Lion his citizenship and wouldn't she come down on her next birthday and receive the honor.

In the months following Lion's passing, Marta curled into a solitary seclusion. The only companions she allowed herself were the animals she encountered on long hikes through the Santa Monica Mountains or during her early morning swims in the Pacific, or else the Villa’s ancient pet turtle. Dejected, she allowed her elegantly terraced garden to revert to nature. Gradually, however, she was coaxed out of her isolation through the solicitude of friends. Slowly her interest in the world regenerated. She busied herself with the stewardship of Lion's estate, negotiating with the trustees of USC to establish their house and its contents as the Lion Feuchtwanger Memorial Library. She continued living in the Villa, over the years shepherding thousands of visitors through its magnificent rooms. In 1961, as the Bel Air fire surged to within a few hundred feet of the manse, imperiling the library for yet a third time,

seventy-year-old Marta heroically stayed behind, supervising its evacuation and watering down the grounds, thereby helping to save them.

Marta's tour of the library would become one of the highlights of a Southern California visit for many world dignitaries. The collection of more than 35,000 volumes included some extraordinary gems, and Marta, a spry gleam in her eye, would take her visitors through a marvelously cadenced walking history of Western Civilization.

You’d be shown an extremely rare Nuremberg Chronicle from 1493; the first Florentine edition of Sophocles, inscribed by Michelangelo Buonarroti; or the first edition of Rousseau's Treatise on the Inequality of Men, inscribed by Beaumarchais to his dear friend Benjamin Franklin, with the latter’s marginalia; or a bound collection of a contemporary Paris journal, the complete series from 1792 to 1814, including transcripts of the hearings of Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, Danton, and Robespierre (a volume initially compiled by Napoleon's brother). As you walked through the house, you’d be shown the recessed organ at which Bruno Walter used to sit and play (as did my grandfather Toch); at one point Marta mighty unexpectedly upend a chair to show you the black-crayoned autograph that the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich left behind after a private recital. The stories would flow with gracious ease. At the end of the tour, you’d be invited to inscribe your name in a guest book that included the signatures of many of the world's leading citizens.

"Nothing human is alien to me," Marta insisted on the last day of our interviews.

Her indefatigable interest in the world would seem to bear that out. The life of Marta Feuchtwanger, born in Munich in 1891, had been subject to many migrations, none perhaps as definitive as the temporal: In her serene old age she resided on the far shore of another continent, on the nether cusp of another century. But through her expansive generosity—in the form of her taped recollections, her announced endowments, but most important, her ongoing presence—she seemed to have spanned them all.

And does to this day, almost forty years after her physical passing.

* * *

UPDATE AND AFTERWORD

The entirety of my four-volume oral history of Marta Feuchtwanger is available online, with detailed tables of contents at the outset of each volume and a complete index at the end of the last volume. For links, see here.

I mention this because the other day, during the worst of the recent LA fires, I found myself drawn back to Marta’s account of her own fierce stand during that dreadful 1961 Bel Air conflagration, how she helped save both the Villa’s well-nigh priceless library and presently the Villa itself. And her telling of the tale (starting at p. 1503 of volume four) was every bit as vivid as I remembered it:

WESCHLER: What about the fire of 1961?

FEUCHTWANGER: Yes, three times we had a fire here, the worst being, as you suggest, the so-called Bel-Air fire of November 1961, which came from far away, from Bel-Air, and jumped over the freeways until it came to Pacific Palisades. But at the same time, there was a fire in Topanga Canyon, which is on the other side of the house. For three days it was burning, and the flames were already below the house, on the one side here in Santa Ynez Canyon. I could see them from the rim; they were much lower than the house itself. There were even people here from Europe, reporters, to see the fire. The ashes of the fire were above my ankles. The whole roof was full of hot ashes. Fortunately this roof is a tile roof, so it was more secure; but houses which had only wooden roofs—shingles—they were much more in danger. Also the fire insurance is cheaper—I didn't know that—with tiles. The sparks came everywhere; even if the fire wasn't right there, the sparks came from above. We had watered the whole thing, the roof and everything, and the ashes—it was absolutely mud: you waded in mud, the water and ashes together. And they evacuated the whole library.

WESCHLER: How did that take place?

FEUCHTWANGER: Oh, it was like this: by chance I discovered the fire. There was a terrible wind, a Santa Ana wind, and there was much noise. And I went out in the night—it was about six o'clock or so—and I went out to see what the noise was. And it was all those trash cans rolling down the street which the wind had driven out from the different houses. I even caught some and put them on the side because I was afraid somebody could run with the car against it. And then, all of a sudden, on the east side of the sky, I saw a red light, red clouds, and this spread immediately, very fast. So I called the [USC] head librarian [Louis Stieg], who lived in Palos Verdes, I called him immediately.

WESCHLER: This was six in the evening or six in the morning?

FEUCHTWANGER: Morning but still dark. And I called him and said that there is fire around, and if he doesn't think that the library should be evacuated. Then I called my gardener, who was a Mexican and very devoted to me—he lived in Santa Monica—and he came right away with his big truck and his wife, and they began to pack. I called Hilde, the secretary, and we packed all the first editions and incunabula in boxes. (I had always boxes with me here, because I thought there could be sometimes a fire. The whole garage was full of boxes.) We began to pack. And then came the head librarian. (He is not here anymore; he is now in San Francisco, I think.) He had sent a big truck here, and then we began to pack the truck. Then the fire department said we have no time—everybody has to be evacuated, there is no time to pack—so we just had to throw all the books into the truck.

WESCHLER: How close was the fire at this point?

FEUCHTWANGER: Oh, it was around the house already.

WESCHLER: I mean literally how many feet away was the fire?

FEUCHTWANGER: It was not "feet." It was on the canyon, over the canyon on the side. There I saw the bushes burning. And it was the hot ashes which were so dangerous.

WESCHLER: Are you saying like a quarter-mile away, about that far, or half a mile?

FEUCHTWANGER: Oh, nearer than a quarter-mile. You could just go down here—you know, there is a little street which is only two houses [Lucero Drive] , and then you see down into the canyon.

WESCHLER: And there was the fire.

FEUCHTWANGER: It was all on fire. And then, what I began with is that the Topanga Canyon fire came from the other side, and when you looked.... Two days it was burning just without any reprieve, but for the first time they used those fire planes.

WESCHLER: With the chemicals.

FEUCHTWANGER: With fire-retardant chemicals. I think it's a kind of boron—it was not water alone. And that was the first time. But at night they couldn't fly. I don't know why. They said, I think, there is a downdraft, and they couldn't see well enough with the flames. But then it was thought it was already over, the fire. Nobody was here anymore; everybody was evacuated but me. I was looking out.

I heard over the radio, of course, always what happened; and then it said that now it seems that they contained the fire. So I was going outside, when all of a sudden I saw the flames coming up again—but very fast. It was just like an explosion.

WESCHLER: In the distance, you mean?

FEUCHTWANGER: Very near. It looked very near. And then I went back into the house and turned the radio on, and it said that now the fire is so near, it has jumped over Mulholland [Drive]—you know, that is the rim road—and there is a fire storm going on. You know, the fire creates its own storm from the heat, and when there is a fire storm, there is nothing you can do but wait until everything has burned out. And then this man said, "And now comes the fire from Topanga; the flames are already on Mulholland, and they are only a quarter of a mile apart; and when they meet, then the fire storm goes all over Pacific Palisades, to the ocean, all down, and the whole Pacific Palisades is lost." That's what I heard. It was ten in the morning. And then I thought, "Now I have to leave, too."

WESCHLER: And everybody else on the street had already left?

FEUCHTWANGER: Nobody was there but me.

WESCHLER: Why were you allowed to be there?

FEUCHTWANGER: I told the fire department, I said, "I don't go away." And they said, "All right, you have to wait until we pick you up in the last moment. If it had been more people we couldn't do it, but one...." I just didn't leave; people with children and so, they had to leave.

WESCHLER: You and your turtle.

FEUCHTWANGER: Ja. Then I wanted to call the fire department what I shall do, but in this moment the wind turned, and all of a sudden I saw the flames going back to the other side of the hills. Everything was burned out from this side. All around it looked like a moonscape.

WESCHLER: Which direction are you pointing to? That's west?

FEUCHTWANGER: That is west, ja, north and west. It was all burning, you know, it was just—it was twenty, thirty feet from the street, you thought. You know, the street where you come up—you must have seen it—it was like a moonscape. Nothing was green anymore, was standing. And then the wind—sometimes the Santa Ana wind changes after three days, so now the wind came from the ocean (it was a damp wind which always comes from the ocean), and the whole flames went over the mountains back again where they had come from. And, of course, there was so much burned already that the flames had no nourishment anymore. So that was the end of the nightmare. But it was just like a miracle that in the last moments the wind changed.

WESCHLER: Was the library damaged in any way?

FEUCHTWANGER: Well, I think the heat wasn't very good for it. Some of the plants were just shriveled from the heat. It was so hot—you can't imagine. When you went out on the street it was like in an oven, you go in an oven. It was the hot wind from the Santa Ana and the fire together, You couldn't even breathe, so hot it was.

WESCHLER: Were the books of the library damaged from the evacuation at all?

FEUCHTWANGER: Yes, much was damaged and also lost, a lot of books. It took four months to bring them back.

WESCHLER: Where had they been taken?

FEUCHTWANGER: They were at the university. And the university took the occasion to make a second catalog. First it has a name catalog, and then they made also a subject catalog there. And with making this catalog, those young people who did that were not very attentive, and they put everything.... You know, naturally, books which were together, also were packed together in the beginning. We packed it just how it came. [But when we got it back], there was Buddha beside a cookbook. We had always wrote on the box what it was about (mostly not what was inside, but in what story it was, you know, the first story or second story). But everything was mixed up. And I think Hilda and I, we lost at least everybody ten pounds going up and down the stairs. When we had the cases upstairs, then the books belonged downstairs. And we couldn't have it all together, all, the whole thing; so in every room, in the middle there were those boxes stacked, and we packed them out. But it took four months until we had all the books here and in their shelves again. In Europe, it was in all the newspapers about this thing. But I didn't want so much publicity here.

WESCHLER: Has that been a problem, publicity? Do you generally keep the existence of the library fairly quiet for security reasons?

FEUCHTWANGER: Yes, you cannot find it, you know. If you don't know where it is, you—everybody passes with the car, because the number is hidden, so near to the edge of the street that you don't see it.

And I'm very glad about that. Most people who come the first time just pass us here.

WESCHLER: As did I.

FEUCHTWANGER: Ja, ja, everybody. And that's what I want. But to my friends, to indicate where it is, I say always look out for 505, because it's across the street. When you see 505, you just have to cross the street. But I don't want that they see my number.

WESCHLER: And in terms of security, there are no guards here at all. It's just you.

FEUCHTWANGER: No. Only the turtle. But he doesn't even bark, [laughter]

WESCHLER: Okay, one other thing that I think should be noted is the incredible way in which you take care of the library. I mean one never finds dust on those books at all.

FEUCHTWANGER: You don't look near enough maybe [laughter]. But you know, there was once in a New York newspaper an anecdote by the columnist Leonard Lyons. He wrote that he was here with other people to see the library—it was still during my husband's lifetime—and they all found that it's so well kept; people even with their fingers went over the rims. And then they asked me, "How do you do that, to keep them so clean?" And I said "Lion reads." [laughter]

WESCHLER: Thirty-five thousand volumes a day.

FEUCHTWANGER: But anyway, when books are used, they don't get so dusty.

WESCHLER: Well, there must be an awful lot of reading. Okay, well, I think we're running out of tape on this side. We'll stop for today.

FEUCHTWANGER: Still nothing to drink? Isn't it almost evening now?

WESCHLER: This is Yom Kippur and I'm on fast. If I've been asking stupid questions, that's why.

Incidentally, as we were researching the Bel Air Fire, my aide de ‘stack David Stanford came upon this official newsreel, put together shortly after the fact by the LA Fire Department, and it feels both very much of its time (those clunky old fire engines, the hyperventilating narrative voice) and like it could have been thrown together the day before yesterday (from the soaring helicopter air drops right down to the desperately collapsing water pressure in the hydrants). Plus ça souffle, I guess, plus c’est la meme…

As mentioned earlier, Marta lived over a decade beyond the oral history, every bit as vivid and sly almost to the very end, in 1987, at age 96. Thereafter, once the bulk of the Feuchtwanger papers, collection and library had been transported to USC, the university moved to put the Villa itself on the open market. But a committee of Friends of the Villa Aurora, based in Berlin but with colleagues all over the world (of which I, by then in New York, was privileged to be one) moved to forestall that sale, raising money from both the Berlin City and German Federal governments to purchase the villa and its grounds and renovate and reconstitute them as an artist’s retreat and cultural center. And ever since 1995, the Villa has operated as such, hosting a succession of artists, filmmakers, composers, musicians or scholars, three or four at a time (many of them from Germany, seeking inspiration from the history of the émigré experience in Southern California), and always supplemented by the presence of at least one political refugee in flight from some specific calamity or crisis somewhere in the current world. There have been over four hundred such medium-term visitors to date. In 2016, the same consortium purchased the old Thomas Mann House on San Remo in the Pacific Palisades flatlands down below and they have since been running that distinguished manse right alongside the Villa Aurora, and in a similar manner, under the collective rubric of the vatmh.org.

And the thing is both of them came under dire threat once again during the most recent LA fires, especially the Villa Aurora up there on its crestline ridge—but somehow, miraculously, once again, both of them, but especially the Villa, survived. It was almost as if they had some kind of guardian angel.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

I am so fascinated by all of this. Knowing that the villa has survived the fires gives me hope and also a goal for the future. I long to see that library and I have saved this for reading again later, and listening to the oral history. Thank you.

Thank you so much for reminding us of this particular diaspora, made up of the finest thinkers, writers, composers and artists of the Weimar Republic. Marta Feuchtwanger seems clearly the optimal storyteller for keeping the legends of that time alive. How fortunate that your discussions took place, so that this sidebar of that grim time in history is not forgotten. Having met or known other intellectual refugees from the Third Reich, I look forward to reading this oral history.