January 19, 2024 : ISSUE # 34

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Friend of the Cabinet Margaret Wertheim has thoughts on the Egg at the Center of it All and then we pick up where we left off last time, with the vast expanse, and expanses yet vaster, both in terms of the workings of the cosmos and of the human (and artificial) mind.

* * *

MAILROOM

Longtime friend of the Cabinet, science writer Margaret Wertheim, of Crochet Coral Reef fame, wrote in with her own take on the Walter Murch/Radiolab/ Middle of Everything spooky-overlap-at-a-distance situation anatomized in our last issue, #33.

Ren: Re the convergence of Murch and RadioLab about humans being at the center of the scale-spectrum of the universe—among physicists this is a well-known fact, much discussed and marveled at. I learned about it when I was a physics student at university more decades ago than I care to admit. Good on Walter for discovering it for himself—discovery is the essence of scientific practice and it’s always impressive when people rediscover in their own way things already known.

To which Ren responded:

Thank you for that—I wonder if that then means that the Radiolab people likewise stumbled their way through already well-trod terrain, or whether theirs (and Walter's?) was an artful charade of fresh discovery of something already well known or at least subconsciously remembered.

And Margaret replied:

Dear R: I haven’t yet heard the Radiolab piece—it’s in my queue. But Steve Strogatz, whom I know, is a leading mathematician of dynamical physical systems, and I'd be amazed if he wasn’t familiar with this before the RL piece. We discussed it in physics school in the late ‘70s and I’ve seen many mentions in physics books over the years.

One way to think about this that I came to a long time ago is that chemistry operates in the middle ground between particle physics (which is about subatomic-scale things) and cosmology (which is about galactical-scale things). Living things are made of molecules, and chemistry (which describes the operation and interactions of molecules) operates in the middle of the universal scale range. Chemistry is the grounding of life—not particles or galaxies. Particles and galaxies are the extreme ends of the physical spectrum—with the very extreme ends being the Planck scale (where there's the foaming froth of virtual particles, the so-called 'quantum vacuum'), and the universal cosmic scale (where there's just space-time). These are considered the sexy aspects of physics, and even of science overall. However, the place where actual sex happens is in the middle of the scale-range, where bio-chemistry is king.

In the realm of science-writing it’s almost impossible to get articles about chemistry published because it’s not seen as cool—whereas you can get any number of articles published about new theories of space-time or new particles. There is a sense in which chemistry is truly the overlooked science, yet chemistry— the middle ground of being itself—is where WE LIVE. This is a prejudice I've remarked on to chemists and they totally get it. As ever, the middle ground is seen as boring and uncool. Yet, as Walter ‘discovered,’ it’s the essence of US.

Cabinet regulars may be enjoying how with those last comments Margaret seems conspicuously to be upending the crusty old John Ford’s directive to the young Steven Spielberg (discussed in Issue #32)—indeed, one can almost hear her counter-grousing “Horizon at the top, boring. Horizon at the bottom, boring. Horizon in the middle, sexy as all hell!”

I do love the way that these ongoing Cabinet threads occasionally seem to cross atop, around, and athwart each other, indeed precisely like threads on a loom, or files in a matrix. Indeed, one sometimes comes across the word “matrix” in the context of the rigging-up of looms. Matrices, whether in textile manufacture or in wider mathematics, constituting a sort of seedbed, from the Latin root “mater,” which is to say “mother,” the root (for that matter) of all “matter.” Binging us back, by a commodious vicus of recirculation, to that Egg at the Center of it All.

* * *

MEANWHILE, PICKING UP WHERE WE LEFT OFF

at the end of Issue #33…

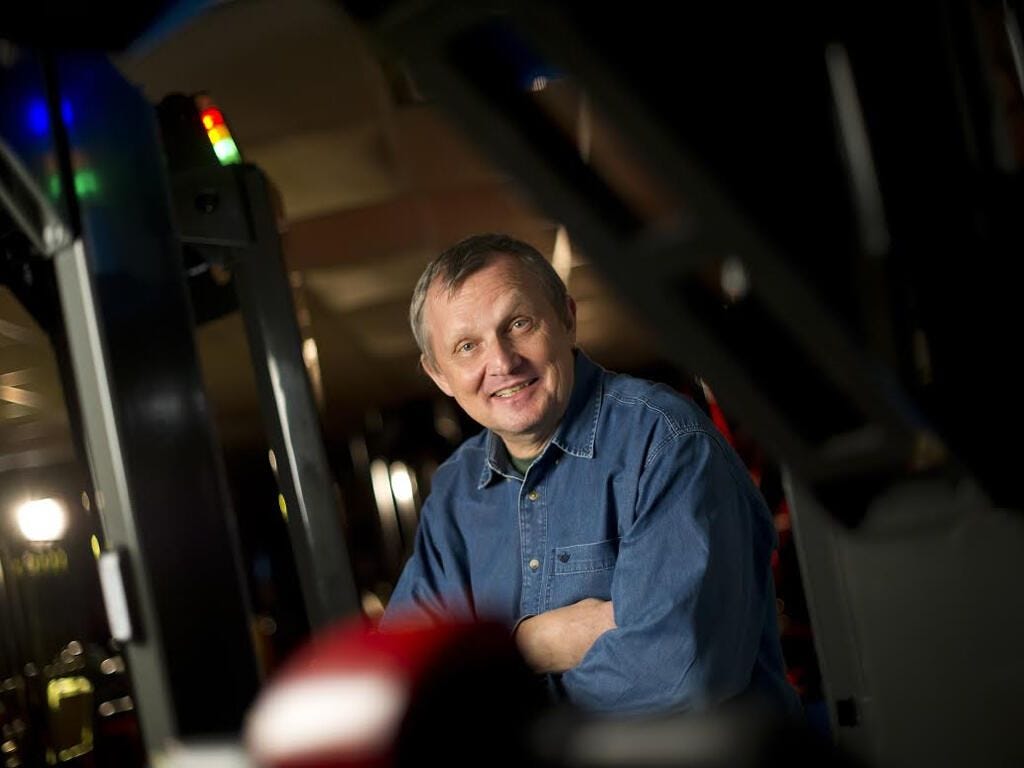

ANYHOW, in the midst of all this conceptual to-ing and fro-ing, Walter reminded me of a fascinating long thread that had broken out a while back at the Quora website when the editors there had prompted their followers with the query, “What is the most fascinating scientific photograph ever taken?” and one of them, a self-identified former science teacher named Mark Gregory submitted an entire sequence of images, starting with this one

Which he glossed as follows:

This is a photo taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2012 of a tiny, tiny section of night sky called the Hubble Ultra Deep Field. It took 11 days of exposure to capture the light from these small dots. What is so mind-blowing about it is the fact that with the exception of four small objects, not a single dot of light in this photo is a star. They are all entire galaxies of stars, over 10,000 separate vast islands of stars spanning quadrillions of miles in size each.

Gregory proceeded to leapfrog from one image to the next, culminating with these:

This one is a closeup of a cluster of galaxies, one of hundreds known to exist. Most of the objects in it are massive galaxies, clustered together by their mutual gravity. It is called MACS JO717 (objects with long cross-hatch lines are stars in our Milky Way).

In short, everywhere Hubble looked in its dozen+ photos, it saw galaxies of stars… thousands upon thousands of them. No one knew the night sky had that many islands of stars. Every Astronomer on Earth was blown away by the realization that when you look out at the night sky tonight, the darkness you see is not dark. It is FILLED with thousands upon millions upon billions of galaxies of stars, each containing hundreds of billions of suns and possibly trillions of planets of their own. In fact, latest surveys estimate that our visible universe contains over 2 TRILLION galaxies, stretching to distances that no one can even comprehend. That is an almost impossible number to contemplate and is so humbling to realize.

Modern computers can draw simulations of what 2 trillion galaxies might look like, if we could see just a tiny fraction of them from a distance. Here is one such simulation (called the Large Scale Structure of the Universe):

Each dot above would be a galaxy of billions of stars positioned by the computer in its correct spot in the night sky. WHOA!

TO WHICH WALTER MURCH (leave it to Walter to be frequenting such sites—anyway, he reminded me how he had) THEREUPON CHIMED IN:

It is incredible. But also incredible is the lack of density in each galaxy. We see each galaxy as a blob (or a point) of light, implying visually that it is solid, but in fact the distribution of stars in each galaxy is 500 trillion (5e14 — five followed by fourteen zeros) times less than the distribution of galaxies in the universe.

There are supposedly two trillion galaxies in the observable universe, with 500 billion stars in each (I am being generous here). Multiply to get the number of stars in the Observable Universe, which = 1e24 (one trillion trillion). Each star is on average 1e18 cubic kilometers in volume. Multiply 1e18 by 1e 24 to get the volume of stars (luminous matter) in the Universe. This equals 1e42 cubic kilometers.

But… the volume of the observable universe is just under 1e72 cubic kilometers. Which means that the volume difference between Universe and the Luminous Matter in it = 1e30. One million trillion trillion times more space than matter.

1e30 is the difference in volume between a 1mm grain of sand and the volume of the planet Earth.

*

And so anyway, I was thinking about all of that (if you can call it thinking when your mind has just been virtually laid waste) when a few days later (as I was anticipating the conversation we ended up having at the Hammer Museum in LA earlier this week about the current state of play in the field of artificial intelligence with our other friend, Google’s VP of Research Blaise Agüera y Arcas), I came upon this passage from a conversation with computer scientist Yejin Choi, a 2022 recipient of the prestigious MacArthur “genius” grant who has been doing groundbreaking research on developing common sense and ethical reasoning in A.I., as interviewed by David Marchese in the NYT Magazine (Dec 21, 2022):

CHOI: …The truth is, what’s easy for machines can be hard for humans and vice versa. You’d be surprised how A.I. struggles with basic common sense. It’s crazy.

Can you explain what “common sense” means in the context of teaching it to A.I.?

CHOI: A way of describing it is that common sense is the dark matter of intelligence. Normal matter is what we see, what we can interact with. We thought for a long time that that’s what was there in the physical world—and just that. It turns out that’s only five percent of the universe. Ninety-five percent is dark matter and dark energy, but it’s invisible and not directly measurable. We know it exists, because if it doesn’t, then the normal matter doesn’t make sense. So we know it’s there, and we know there’s a lot of it. We’re coming to that realization with common sense. It’s the unspoken, implicit knowledge that you and I have. It’s so obvious that we often don’t talk about it. For example, how many eyes does a horse have? Two. We don’t talk about it, but everyone knows it. We don’t know the exact fraction of knowledge that you and I have that we didn’t talk about—but still know —but my speculation is that there’s a lot. Let me give you another example: You and I know birds can fly, and we know penguins generally cannot. So A.I. researchers thought, we can code this up: Birds usually fly, except for penguins. But in fact, exceptions are the challenge for common-sense rules. Newborn baby birds cannot fly, birds covered in oil cannot fly, birds who are injured cannot fly, birds in a cage cannot fly. The point being, exceptions are not exceptional, and you and I can think of them even though nobody told us. It’s a fascinating capability, and it’s not so easy for A.I.

I snipped out that passage and sent it off to Walter, who responded with a passage from his forthcoming memoir/summa:

Hans Moravec—a generation younger than Minsky—articulated that the reason chess seems difficult is precisely its newness, but its reliance on chains of logic makes it easy to program; and the reason catching a ball seems natural and easy is its “oldness,” and this oldness—its deeply encoded nature—is what makes it difficult to program. This became known as the Moravec Paradox: simply stated, it says that, from an AI point of view, what seems easy is hard, and what seems hard is actually easy. Or, as Moravec himself put it:

Encoded in the large, highly evolved sensory and motor portions of the human brain is a billion years of experience about the nature of the world and how to survive in it. The deliberate process we call reasoning is, I believe, the thinnest veneer of human thought, effective only because it is supported by this much older and much more powerful, though usually unconscious, knowledge. We are all prodigious Olympians in perceptual and motor areas, so good that we make the difficult look easy. Abstract thought, though, is a new trick, perhaps less than 100 thousand years old. We have not yet mastered it. It is not all that intrinsically difficult; it just seems so when we do it.

So there: near-infinite expanses in every direction, with regresses and progresses at every register.

Go figure. And for today, anyway, over and out.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

The Animal Mitchell archive .

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

With Ren off to Amsterdam for an assignment on the big upcoming Vermeer show at the Rijksmuseum, we’ll dip into The Archive for an earlier piece of his on Vermeer’s Vermeer and Tim’s.