WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

With the subsiding of the old and at the cusp of a fresh new year, what better time for a whole trill of entries on things being right-side up and upside down: Mondrian, Steven Spielberg, and John Ford; a mysteriously haunting print of unknown provenance; from Malevich to Bruegel in just five minutes; and more.

* * *

THE MAIN EVENT

A year’s end trill of entries around the theme of being right-side up and upside down.

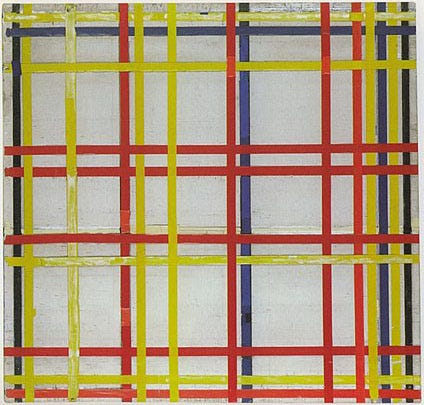

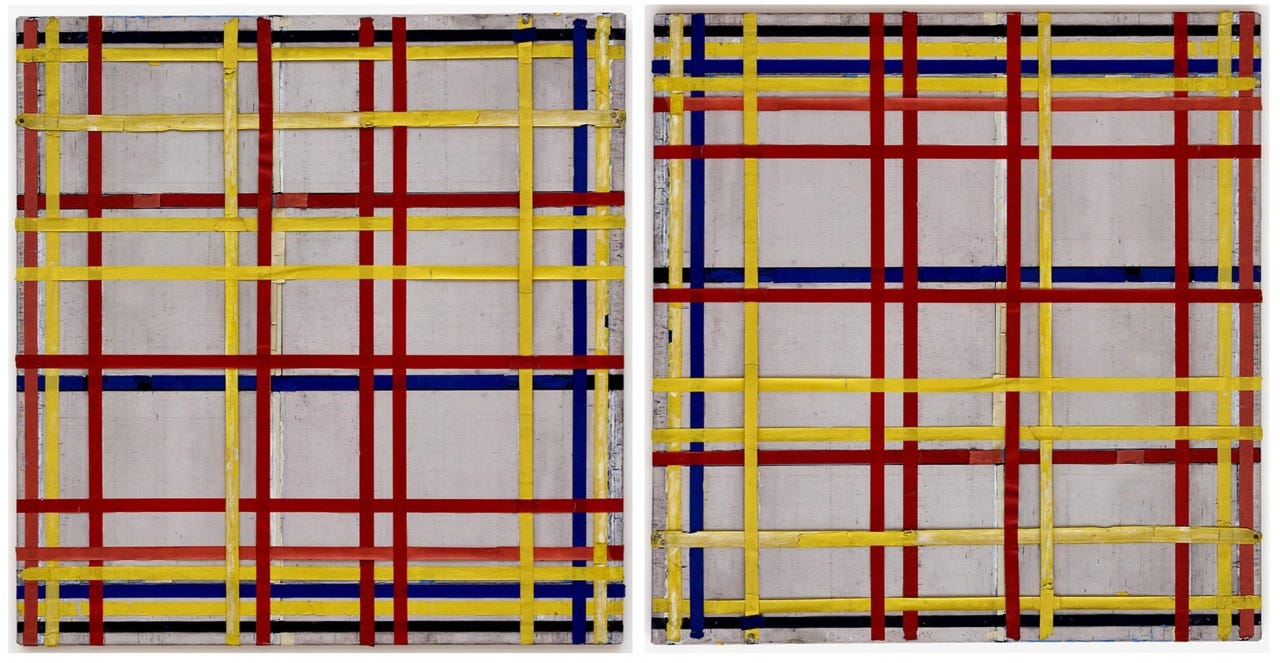

Many of you will recall the whole kerfuffle, a few weeks back, when it was discovered that a classic, indeed iconic, stretched-colored-tape piece by Piet Mondrian, from 1941 (early in the artist’s exiled tenure in New York in flight from the wartime horrors back in his native Netherlands), may have been—hell, probably has been—hanging upside down for over seventy-five years now at its current home at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Dusseldorf. (See, for example, coverage of the imbroglio here.) This according to the museum’s own curator, Susanne Meyer-Büser, who grounded her assertion on all sorts of evidence, my own favorite being the appearance of the piece, hung the other way around, in the background of a fashion spread in Town and Country that had been shot in Mondrian’s own studio a few years after the work’s creation, in June 1944 (the D-Day issue, as I like to think of it, speaking of world-upending events).

Fun how quickly after alighting in his new home Mondrian had established himself as the very quintessence of fashionable modernity—and fun, too, how over seventy years later, being dressed in all-black remains the quintessence of a certain sort of fashion statement. Fun, as well, to think about the ways that the ubiquitous vantages from out of Manhattan highrise windows

must have impressed the modernist master’s sensibility, the back and forth of those impresses: the block-like passages of absolute painted color from his earlier paintings giving way to thin colored-tape echoes of windowpane gridwork itself. An effect rendered all the more uncanny, of course, since going all the way back to the Renaissance, the metaphor of the painting as a perspective window slotted into the wall had itself been well-nigh ubiquitous (and how, for that matter, an intervening window grid had constituted the very basis for Durer’s perspective drawing apparatus, circa 1600). Leave it to Mondrian, though, under this new thrall to the windows of New York City, to be the one suddenly to focus on the grid itself.

The scandal of the painting’s upside-down hanging naturally leant itself to all sorts of knowing guffaws among the legions of modernism’s long-time committed skeptics (the sorts of people who, in Kurt Vonnegut’s characterization, had long considered modern art to be nothing more than a conspiracy between art types and rich people to make everybody else feel stupid): Now who was looking stupid?

And yet, who’s to say? For one thing, can we really be sure whether Mondrian, who didn’t (as per his usual habit) sign the back of this piece, ever did decide for himself which side was up? He often flipped his canvases back and forth before finally committing. And who’s to say whether it wasn’t the art director for the Town and Country photo shoot who flipped the canvas for the internal purposes of that particular shot?

The point is, this particular canvas seems to lend itself to either orientation. It really doesn’t matter (both seem valid), while, at the same time, granted, the choice changes everything. The barometric pressures animating the piece flip entirely.

With the parallel lines bunched tighter at the bottom, one has the feel of looking out and up at an empty airy expanse beyond a bottom window sill. The other way, our gaze seems pressed down by the ceiling (or alternatively a tight-compressed array of raised louver-blinds). (Although, further alternatively, on third thought, we are invited to ignore the orientation either way, bracket out the airy beyond, and hone in instead on the surface patterns coursing criss-cross the flat canvas expanse.)

In any case, there’s nothing to be done. Curator Meyer-Büsey explained how the piece is just too fragile (some of the stretches of tape hanging on by mere threads) to be flipped, no matter what. We’re just going to have to go on living with the thing the way it is. Hardly the end of the world.

*

As it happens, just a couple days after I caught wind of the Dusseldorf Mondrian controversy, I happened to attend a screening of The Fablemans, Steven Spielberg’s latest, a thinly veiled autobiographical rhapsode on the thoroughly dysfunctional (and yet, at another level, oh so deeply nourishing) family taproots of his own cinematic vocation. Those of you who have seen the film will know—and as for those of you who yet haven’t, you might still be familiar with the incident I am about to relate, since Spielberg has frequently told the story in other contexts, as for example here, though (spoiler alert!) if you want to be spared the details you’d better start intoning la-la-la-la-la or else just skip over this next section entirely, for the time being—anyway, you will know that the film culminates in a scene where the young would-be novice filmmaker, visiting a studio lot, finds himself being ushered into an audience with the venerable crusty old master director John Ford, who asks the boy what he knows about art and proceeds to subject him to a catechism quiz. “Go over to that far wall,” Ford tells him,

“and look at that painting on the left, and tell me what you see.” Two guys on horseback, baby Spielberg stammers. No no no no no, vesuviates the old director, where's the horizon? Horizon’s on the bottom. Okay, correct, now go over to the picture on the far right and tell me what you see there. Five cavalrymen crouched in the dirt, hazards the hapless rookie. No no no no no, grouses the old veteran, the horizon’s on the top!

Whereupon, the old man offers up his sole summary lesson: “Horizon on the bottom: interesting. Horizon on the top: interesting. Horizon in the middle: boring as shit. Now get the hell out of here.”

A lesson which, as we will soon be given to see in the film’s final delicious grace note of an ending, left quite an impression of the budding filmmaker. And for that matter, as you can well imagine, left me, so recently entrammeled by the Mondrian shemozzle in Dusseldorf, thoroughly drop-jawed as well.

*

Coming home that evening, I stopped in my hallway before a sepia ink print I’ve long cherished. I wish I knew the name of the artist (if you do, please let me know!); I received it in bequest from my dear collector aunt and uncle, the Feiwels.

Anyway, one of the things I’ve long admired about the print is its throbbing ambiguity, how you can’t decide whether you’re on your back in the grass looking up past the treetops at the drifting clouds above—or rather, atop some mountain top, looking down past the intervening trees at a gathering fog sea down below.

The image shimmers back and forth. Horizon at the top, as I now realize, horizon at the bottom. Back and forth, simultaneously both at once.

*

INDEX SPLENDORUM

That print, in turn, has long reminded me of an incredible short video by the Canadian master Mark Lewis, usually screened (as it should be) at full size in its own alcove at art museums though featured several years back as a NY Times video. Entitled Algonquin Park, Early March, it effectively takes one from Malevich to Bruegel in under five minutes. Relax: it’s a nice slow burn of a piece and well worth the four minutes (even if for the first two it may not seem like anything is happening), and you can experience it here.

So what was that?

As I say, a simple clean transit from Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) to Pieter Breugel (1525-1569) in under five minutes.

Which may in turn help account for this pair of self-portraits (otherwise somewhat mysterious on the part of the consummate modernist Malevich):

But talk about horizon at the bottom melting into horizon at the top!

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

The Animal Mitchell archive .

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

From the Archives, a further take on Mondrian, and specifically a fresh look at his Broadway Boogie-Woogie, opening out onto a meditation on the ongoing dialectic between ethnic cleansings and cosmopolitan flowerings. And more…

I loved this one.

Re Ford and art: https://www.dropbox.com/s/fliinaorm07im52/Influence%20of%20Art%20on%20John%20Fords%20Movies.epub?dl=0