December 23, 2021: Issue #6

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

This week: Pashgian, Hutton, and Godot. Starting off with the Director’s Cut of my recent NYT piece on Helen Pashgian, the visionary pioneer LA Light and Space master only now, at age 87, beginning to receive her due; then a video of a further talk of mine about Pashgian in the context, among others, of Vermeer, Descartes, Camus, and ancient Pre-Socratic views locating the seat of vision in the lungs; a celebration of that other master of light in all its sinuous amplitudes, filmmaker Peter Hutton (in Iceland!); and finally, waiting for Godot at airports, and other such captions forlornly awaiting their cartoons.

* * *

THIS ISSUE’S MAIN EVENT:

The Director’s Cut of my recent NY Times piece on

HELEN PASHGIAN IN SANTA FE

The Confounding Lightness of Helen Pashgian

Helen Pashgian recently took a break from a museum install here at SITE Santa Fe to recount one of the defining moments of her life, how around age three she had accompanied her family from their comfortable lodgings in Pasadena across an enchanting three-hour drive to their summer home, a ramshackle cabin in a secluded cove just north of Laguna Beach, from whence she and her father had immediately headed down to the shore (“me with my tiny legs valiantly trying to keep up with him and his long strides”), where he established himself on an outcropping from which he fished and supervised her as she strode into the shallow tidepools, puttering about, poking baby sea anemones (“Ouch!”) and collecting tiny paper-thin concave abalone shells dislodged from the surrounding rocks by a recent storm.

Suddenly, as she recalled, she really noticed, as if for the first time, the way that light shimmered off the windswept surface of the water, and then less than a foot beneath that, the way that the same light likewise shimmered but in a completely different way off the scalloped sand swaths just below. “Now granted,” she explained, “my little three-year old brain couldn’t really make out what was going on, but I was completely captivated by the interplay of all that light.” She paused before sighing expansively: “And I remember it as if it were yesterday.”

It was not yesterday.

In fact, it was almost eighty-five years ago, and in the meantime that light-besotted toddler grew into a tall, lanky light-besotted teenage tomboy (swimming team, surfer, intrepid explorer of the towering mountain slopes just beyond the family’s Altadena manse) and then a light-besotted collegian and academic, specializing in art history (and specifically Vermeer and Rembrandt and the light-besotted artists of the Dutch Golden Age)—moving through Pomona College on to graduate work at Columbia and Boston University to the brink of a final PhD push at Harvard, when she instead demurred. In another pivotal moment, just around that time, she suddenly woke bolt upright one night to the twin realizations that she had to return “to the eucalyptus scent and, of course, the diaphanous light, of Southern California,” and to find some tangible way of engaging (she wasn’t yet sure how, though definitely not academically) with that actual light.

Which is how she became one of the founding members of the group of artists (including Robert Irwin, James Turrell, Peter Alexander and others) who would forge the Light and Space movement that came to epitomize the Southern California art scene of the late sixties and seventies and ever since. Albeit one of the least well known. That is, until relatively recently.

“How did you go bankrupt?” Hemingway has one of his characters in The Sun Also Rises ask another. “Two ways,” comes the reply: “Gradually and then suddenly.” In Pashgian’s case, one might well ask what the opposite of going bankrupt is, for the sun of widespread acclaim has at long last risen high atop her steady five-decade career, and with a happy vengeance.

Although things began to turn for Pashgian, in terms of that long-delayed recognition, back in 2011, with the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time reappraisal of local art history, 2021 has been proving the real annum mirabilis when it comes to things Pashgianian (incidentally, she insists on pronouncing her name Pash-KIN), with the past month in particular seeing successive openings, one after the next, of her first New York gallery show since 1971 (at Lehmann-Maupin’s 24th street outpost in Chelsea, through January 8); this full-on retrospective at SITE Santa Fe (through March 27); and then a big Light and Space show at the Copenhagen Contemporary International Art Center (through April 9) in which for the first time her own contribution to the movement is being foregrounded. In addition, Radius Books, with perfect timing, is releasing an exceptionally sumptuous full color monograph on her Spheres and Lenses.

*

Pashgian regularly gets asked whether she thinks the way her work had so long been slighted was on account of her being a woman (after all, for example, when several of the other artists in the movement were included early on in a group show at their Ferus Gallery, they had titled it—granted, with a certain tongue in cheek—“The Studs”). But her answer is always the same, as it was once again during that Santa Fe conversation. “No,” she pronounces simply, definitively. End of discussion.

Others, however, disagree: for instance, James Turrell. As it happens, Turrell likewise grew up in Pasadena (his father was the principal of Pashgian’s high school, and their families were friends) and he also went to Pomona, though what with his being eight years younger, they had relatively little actual interaction until the past few decades. (Pashgian recalls still another pivotal moment when, attending a Presbyterian beachfront summer camp as a young teenager, she used to sneak out every morning before dawn to watch the sun rise. “The water would be still and glassy, the atmosphere dense and moist, and the light would gradually swell,” she recalls, “and suddenly there would be this incredible pink flash, the whole world going intensely pink, though just for a few seconds, at which point the sun would emerge from beyond the horizon to the east, washing the pink away. And the thing is, eight years later, Jim (as I will always insist on calling him) went to the boy’s version of that same camp. And a few years ago, I asked him whether he too had ever gotten up early and experienced the—and he interrupted me, exulting, ‘The Pink Flash!’ For indeed he had, and he too felt that epiphany to have been central in his own eventual formation.”)

Anyway, reached by telephone, Turrell insisted that “Of course she was handicapped on account of being a woman. In fact, she had three things going against her: she was a woman, she was beautiful, and she came from a family of some means. So there was no way she was going to be taken seriously in that macho competitive environment. But thankfully, at long last now she is being, it’s about time, and she deserves every bit of it.” Turrell paused, before continuing: “I suspect that one reason she is so insistent that being a woman wasn't held against her in the early days is she doesn’t want to see merely being a woman as weighing in her favor today.”

“I just kept doing my work, head down,” Pashgian now related during that install tour, “and frankly I preferred to be doing it by myself. Indeed, I pretty much stayed in Pasadena the whole time, which as far as those guys on the west side were concerned was just about as far removed from all the action as Georgia O’Keefe and Agnes Martin were out here in New Mexico, and I did so for the same reasons as they did, and to the same benefit. Anyway, I was hardly being entirely ignored, I had a steady albeit smaller gallery presence. And then, too, it took a long while for the materials I was exploring—the resins and the urethanes and the epoxies and so forth—to advance to the point where I could really begin doing what I wanted with them.”

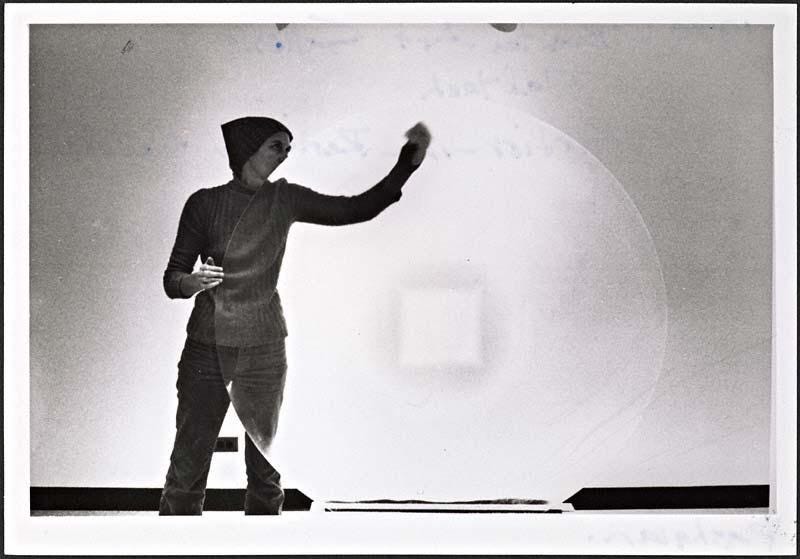

Her own doing the work, hands-on and by herself, unlike many other artists (viz Koons and the like), has always been at the center of her practice. She described how soon after her return to California, she’d been invited to spend a year, along with a few other artists, exploring the artistic potential of some of the sorts of new-fangled materials that were just then being declassified by the military. She brewed up a thick sixty-inch-diameter block of polyester resin, a material of almost ludicrous lethality, and then spent weeks striding about atop it, sanding down its edges by means of ludicrously heavy power-equipment, culminating (following a seemingly endless polishing regime, under the supervision of fabricator extraordinaire Jack Brogan {see her recollections in Part 2 of my Brogan profile, here}), in the giant gleaming lens, mounted atop a low pedestal, that then proved the unquestioned hit of the artists’ summary exhibition at the Cal Tech gallery.

Indeed it was so prized that within a few nights of the show’s opening, somehow it ended up getting stolen, never to be seen again.

Unfazed, Pashgian persisted. While most of the other Light and Space artists (having arrived by way of painting) were busy successively dematerializing the object, Pashgian seemed to come from the other side, attempting to fashion objects that veritably materialized light. She went on to create a brace of gloriously colorful, bowling-ball sized spheres (clear colored epoxy encasing cast acrylic forms), the interiors of which seemed to morph disconcertingly from moment to moment as the viewer toured round them.

Likewise, subsequently, with a series of glowing flat pieces which seemed to burrow deep into the wall, that is until the viewer moved, at which point the interior forms seemed to warp and then disappear entirely.

Twenty years on, she continued her aesthetic investigations, but she tended to recede somewhat from the art world proper for a couple decades in order to care for her aging parents (another female tendency) and to devote more serious time to supporting her beloved alma mater, Pomona College, as a full-fledged trustee. But around 2006, she plunged once more into full artistic commitment across a series of ever more sublimely confounding pieces.

For starters a new series of lens works—thirty, forty-five and presently sixty-inch discs produced in exactly the opposite fashion from the stolen one at Cal Tech. “I began to experiment with a sequence of thin urethane pours into a shallow concave mold: twelve, fifteen, eighteen layers per piece, each evincing a slightly different pigmentation across slightly different sized spreads” (the trick being how to keep the colors pure, so that they didn’t turn all muddy when seen, one behind the next, once the resultant lens got mounted on its translucent pedestal).

The urethane was not quite as dangerous to work with as the polyester resin, though it did contain cyanide, so Pashgian, by herself in her alchemical lair, still had to be masked with respirators and goggles. By trial and error (“I ended up throwing out fifteen or twenty such pieces for every one I kept”), she developed exacting protocols for the successive pours—fifty steps at a time laid out in painstaking order. “With those pieces, half the work is technical and half aesthetic, and I have to divide my focus between the two registers, completely committed to one or the other from one moment or the next.”

But the results (both Santa Fe and Lehman Maupin feature several examples) are breathtaking.

Faced head on from the far side of a room, properly lit (at their best when illuminated by recessed raking lights on a five-minute dimming-dawning-and-brightening timed rotation) they appear to hover, a mist-like cloud of not-quite-sure what (a smudge? a bruise? an insubstantial fogbank? a solid globe? a mere afterimage? maybe nothing at all), pulsing through various configurations of expanse and tinge. (Faced from the side, they suddenly reveal themselves to be a shallow concave form, sheer as a blade, a throwback perhaps to those paper-thin abalone shells from Pashgian’s toddlerhood.)

Pashgian avers as to how she loves getting the eye and the mind working against each other in a vertigo at the very cusp of knowing.

At times the apparition seems momentarily to congeal into an eye looking back upon the viewer, and the effect can get to be almost existential: “For there is no place that does not see you,” as Rilke insisted. “You must change your life.”

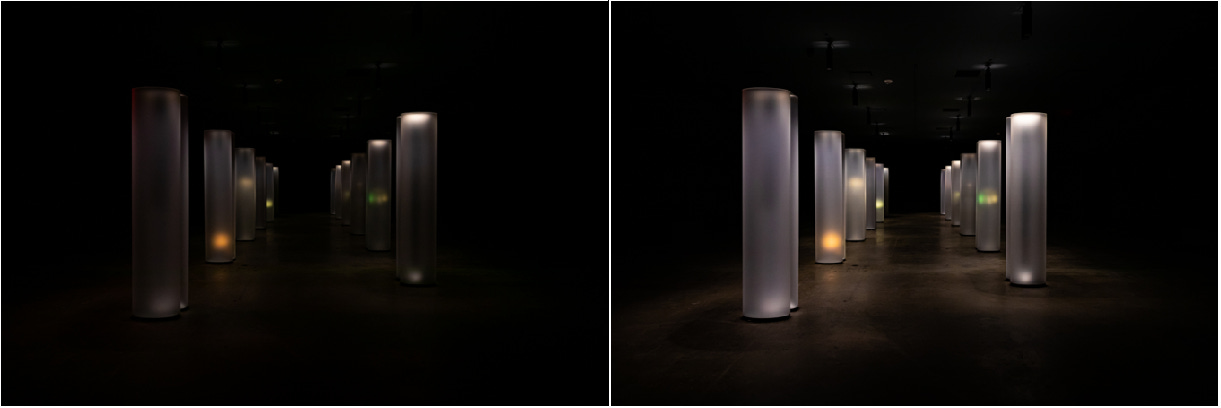

The piece de resistance of the SITE Santa Fe show, however, is on loan from the LA County Museum (whose director, Michael Govan, has become a huge Pashgian fan): across a darkened hangerlike expanse, a ghostly colonnade of twelve tall translucent double-columns (fashioned out of molded acrylic sheets, inside the hollow of each, Pashgian has secreted a different tangle of mysterious reflective forms that project a continuously morphing shadowplay of image and color onto the outer skin of the diaphanous tubes) which get mysteriously lit somehow from above, once again on a dimming-dawning-brightening five-minute cycle.

Walking by you see things and then you don’t, an effect both futuristic and deeply primordial.

The sumptuous Radius volume notwithstanding, it is almost impossible to capture Pashgians with still photography: even capturing her own lively gleam can be difficult. For the rest, though, it helps to have recourse to video, which can evoke a bit more, though hardly all, of the experience of being in the presence of these works. Consider, for example, these three efforts from off my own iPhone:

View them here, here, and here.

The SITE show bears the name “Presences.” Presence, as it happens, being the diametrical opposite of present-tense immediacy, implying as it does being-across-time, duration, which Pashgian has come to feel is the very quintessence of the experience of light.

Speaking of time, asked how it felt at long last to be mounting this career-summing retrospective in Santa Fe, the 87-year-old Pashgian shot back, almost noncomprehending: “What are you talking about? This is merely a mid-career survey. Wait till you see what’s coming!”

* * *

A-V ROOM

My Talk at SITE Santa Fe with further thoughts (granted, in some instances, pretty far out there) on Helen Pashgian

Since I was going to be in Santa Fe covering the Pashgian opening a few weeks back, the folks there asked me if I might be willing to give a public talk on some wider aspects of the Light and Space movement, about which I’ve been writing for years, ever since my first book, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, on Robert Irwin. I suggested a lecture on the Light of LA itself, and they advertised the topic for the Saturday morning of the show’s opening. But during the night before, as I was writing my piece for the Times, I realized that I had a lot more to say about Pashgian than I was going to be able to squeeze into the strictures of that form, and so, on the spur of the moment, I reversed field and pulled together a powerpoint thread along Pashgianian lines instead. Meanwhile, I learned, just as pretty much everyone in the audience was going to have heard by morning, that the legendary art critic and well-cherished denizen of Santa Fe, Dave Hickey, had died that very evening (he had been in failing health for some time). So I decided to begin my talk with a few words in Dave’s sweet memory, then to devote a few minutes to the light of LA so as not to disappoint any particularly devoted fans of that topic who’d only roused themselves from bed owing to its promised appearance in my remarks, before turning to the core of the talk, which would concern some other ways of thinking about Pashgian’s achievements.

Oh, and one other thing you should perhaps know before watching this video of my presentation, is that I had a terrible case of laryngitis and could barely talk at all—but SITE Santa Fe has a truly crack tech crew, and they figured out some way of miking me up that allowed me to deliver the whole talk in a gravelly hush. It actually worked great: the audience had to lean in tight so as to catch my drift, and the whole thing turned into an almost intimate experience. In fact, maybe I should contrive to contrive laryngitis from now on. Though you may not agree. Anyway, just wanted to explain all that (and no, there’s nothing wrong with your audio equipment).

* * *

FROM THE INDEX SPLENDORUM

Helen Pashgian’s work reminds me of something that that other great California master Wayne Thiebaud once said about Giorgio Morandi, the sublime Italian painter whose lifelong work seemed to focus on one collection of bottles after another after another and hardly anything else, how in fact, as Thiebaud said, “His work is stamped with the love of long looking.”

That comment, and Pashgian’s parallel implicit assertion that truly engaging light itself likewise rewards, maybe even requires, a posture of prolonged and slowed attention in turn put me in mind of another hero of mine, the late and extravagantly well-beloved independent filmmaker Peter Hutton, based through much of his later years up the Hudson at Bard College, whose cinema studies program he helmed right through his premature passing in 2016.

I could commend any number of his short silent films to you (Budapest Portrait; Lodz Symphony; Time and Tide; Landscape for Manon; At Sea; Two Rivers), pretty much all of them steeped in the specifics of a sense of place and suffused with a devotion to the splendors of deep looking (a gaze rendered all the more poignantly penetrating by the hushed silence of its surround). The trouble is that, as with many films of this ilk, they really need to be seen in the dark of a theater across the breadth of a wide screen; the problem being that they seldom get programmed and hardly ever near you. Nowadays, of course, one has access to an approximation of the experience by way of YouTube or Vimeo, though usually such renditions are second-generation at best and beset with all sorts of broadcasting flaws, not the least of which is how you end up watching them compressed into the squeezed confines of your laptop or, worse yet, smartphone.

Still, in this context I am reminded of a scene from late in Hermann Hesse’s 1927 novel Steppenwolf. Does anyone still read Steppenwolf? Back in the day, which is to say the late sixties and early seventies, it seemed as if everyone was doing so, we were all completely entrammeled, or imagined ourselves to be—though attempting to reread the book recently I can’t imagine what we thought we were reading, or why. Very weird book.

And yet all these years later I still vividly remembered a particular passage, and there it was: the protagonist, a grumpily alienated and self-involved, self-torturing anti-bourgeois soul named Harry Haller has entered the Magic Theater at the culmination of an extended quest (don’t ask), where at a certain point he finds himself communing with a version of Mozart, who he finds, to his profound consternation, repairing a radio, a newfangled lowlife device that the priggish Haller finds especially appalling. Presently Mozart completes his ministrations on the busted contraption, turns the knob, and pronounces with deep satisfaction, “Munich is on the air: Concerto Grosso in F Major by Handel!”

“My God,” Haller cries in horror, “What are you doing, Mozart? Do you really mean to inflict this mess on me and yourself, this triumph of our day and the last victorious weapon in the war of extermination against art?” There follows a good deal of righteous overwritten condemnation of the scratchy reception, the cursed pops and wheezes, the oozing distortions and excremental degradations, the manifest inadequacies and insuperable desecrations—but Mozart cuts Haller short, acknowledging all of that and yet insisting how even so, the transcendent essence of the divine music still somehow manages to shine through.

“Please, no pathos, my friend!” the master insists. “Anyway, did you not just observe the genius of that ritardando? An inspiration, eh? {…} Let the sense of that ritardando touch you. Do you hear the basses? They stride like gods. Let this inspiration of old Handel penetrate your restless heart and give it peace. Just listen, you poor creature, without either pathos or mockery, as from far behind the veil of this hopelessly idiotic and ridiculous apparatus the form of the divine music yet passes through. Pay attention and you may yet learn something.”

[Excerpts from the first revised edition of Basil Creighton’s 1929 translation, Holt Rinehart 1963, pp. 211-13, with a few judicious tweaks of my own.]

There follows a fairly endless and insufferably literal-minded explication of the symbolism of this parable, and yet, somehow, the vivid aptness of the allegory likewise still shines through, to me anyway, all these decades later. And pertains to our situation at this very moment, as I am about to steer you toward a YouTube version of what may be my single favorite Peter Hutton short film: Skagafjordur, his breathtaking thirty-minute evocation of a sequence of Icelandic lightscapes, from 2002-04. Do try to look past or through the infelicities of broadcast reproduction, and prepare to give yourself over to another sort of Pashgianian thrall: light veritably stretched across time.

* * *

Speaking of slowed waiting…

FROM MY COMMONPLACE BOOKS

{Beckett et alia}

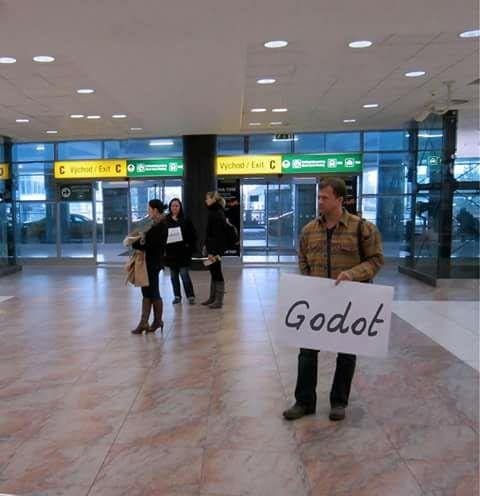

The above image has been caroming around Twitter recently, as best as I can tell being a photo prized back in March at the Prague International Airport, whether by an impressed passer-by or a co-conspirator-in-waiting, I can’t quite tell. Furthermore, it turns out that the meme has something of a history (whether known or not by our Czech Estragon, I cannot be sure). At any rate, back in 2013, this other fellow showed up at the Dublin airport, swathed in chauffeur’s garb, in an apparent effort to advertise a production of the play at that season’s Dublin Theater Festival.

And for that matter, the artist Jonathan Monk was apparently doing the same thing as early as 1995-7 as part of his “Waiting for Famous People” series. Maybe the others just got the idea from him (or else, this all explains where Godot has been all these years, his just being an exceptionally busy and farflung guy is all: the Tooth Fairy, as it were, of Despair).

{Dept. of Loose Synapsed Free-Associations: see this, from the first Transformers movie.}

All of this meanwhile reminds me of the fact that Beckett himself had once intended to become a commercial pilot, or so the late Dierdre Bair recorded in her 1978 Beckett biography, going on to quote one of his letters: “‘I think the next little bit of excitement is flying,’ he wrote to McGreevy. ‘I hope I am not too old to take it up seriously nor too stupid about machines to qualify as a commercial pilot.’” Those lines having served as the epigraph for one of the great Ian Frazier’s most sublime Shouts and Murmurs efforts at the New Yorker (January 5, 1986). Entitled “LGA-ORD,” it launched out, “Gray bleak final afternoon ladies and gentlemen this is your captain your cap welcoming you aboard the continuation of Flyways flight 185 from nothingness to New York’s Laguardia non non non non non nonstop to Chicago’s O’Hare and from there in the passing of gray afternoons to empty bleak eternal nothingness” and so forth, spiraling relentlessly downwards from there (as it happens the whole piece shows up on the Googlebooks sampling of Frazier’s collection, Dating Your Mom, here, but you really owe it to yourself to just go out and buy the whole book which, from the title piece onward, offers up a veritable cavalcade of such existentially charged hoots).

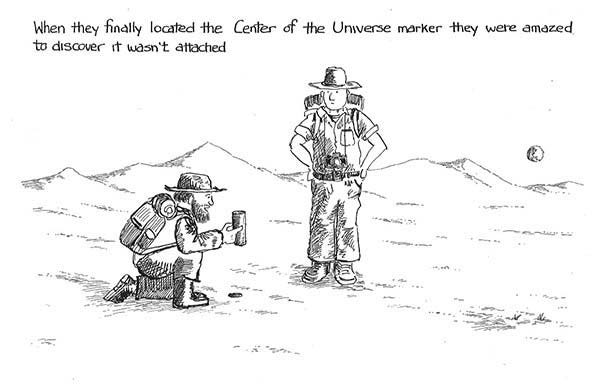

The point being that I like collecting photos of such happened-upon real life instances that would make great gag cartoons (incidentally, the waiting for Godot at the airport trope actually did, perhaps inevitably, make it into such a cartoon, back in 2014, as you can see here).

But my commonplace books also teem with a variation on that theme, which is to say happened-upon snatches of overheard conversations that would make fine captions for as-yet-non-existent cartoons. The first of those that I collected occurred back in 1981, shortly after I’d been hired by the New Yorker, when I happened to be sitting at an outdoor café in Carmel, waiting to meet up with a friend, when I overheard two women of a certain age and class (an age much younger, it occurs to me, than I am now, though still higher in terms of apparent wealth), seated at the table behind me, and one was saying to the other,

“The thing is, I don’t want a job…I want, I want, I want to FOUND something.”

It seemed to me at the time that the proclamation would make the perfect caption for a certain kind of William Hamilton cartoon. I recorded it in my notebook and even offered the snippet to Hamilton when I got back to the New Yorker offices a few weeks later—but nothing ever came of it. Poor guy, he may have been besieged by this sort of thing all the time, but still…. Ah well.

Nor has anything come of any of the others I’ve collected over the years. Including, for example:

Overheard at an antique photo trade fair, one guy holding up a piece and asking his advisor:

“Do I like this?”

Or, two ladies in stiletto heels traipsing about just in front of me among the stalls at Miami Art Basel, as one of them confides to the other

“The thing I love about this fair…are THE SHOES!”

Or the comment a friend of mine reported from an acting class he’d been attending:

“The thing I really hate about acting is how I just can’t be myself.”

Maybe one of these days we could even make a contest out of it. Sort of the opposite of the New Yorker’s own caption contest. Stay tuned.

*

P.S. Fans of the “Bovine Derrida-Nabokov Convergence” from back in Issue #2 may enjoy my daughter Sara’s recent catch from the New York Times of December 4, a pull-quote from an article about rural flooding in Washington:

“The cows were just screaming at me.

It was, it was just total chaos.

And there was nothing to deaden the sound.”

(Those unfamiliar with that earlier entry and/or unwilling to go back and look it up, will have no idea what the hell we are talking about. Ah well, ah well.)

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

And yet, and yet… Misgivings about the rampaging onslaught of the digital, and (especially within the context of this current Substack initiative) misgivings about those misgivings, and further misgivings yet: a whole cognitive gyre. A Norwegian medieval monk’s help desk. A conversation with Bob Garfield about E.M. Forster’s uncannily prescient 1909 novella, The Machine Stops. And more!