WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

A visit with Russian émigré pianists Pavel Kolesnikov and Samson Tsoy as they ply the borderlands between the musical and visual arts.

* * *

The Main Event

A conversation with Russian émigré pianists

Samson Tsoy and Pavel Kolesnikov

as they cross back and forth between disciplines

A bit over a year ago, I was visiting my friend and frequent subject David Hockney for tea at his London digs when he invited me to stay on: his friend the curator Norman Rosenthal (in the midst of helming the big Hockney retrospective slated for Paris’s Foundation Louis Vuitton for this coming spring) had arranged for a pair of his friends, the young Russian émigré pianists Samson Tsoy and Pavel Kolesnikov, to come over later that evening so as to offer a private four-hand concert for David and a select group of friends. A Yamaha concert grand piano had just arrived and was being set up in the artist’s studio next-door and tuned as we visited.

David’s hearing, alas, has been growing ever more attenuated (he has had to give up his operatic collaborations), so the opportunity to sit right by the piano as the two elegant young men played was especially auspicious. In the event, after the two arrived and the rest of us streamed along with them into the side-studio, they presently tore into a shattering four-hand one-piano rendition of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, followed after a brief intermission by a performance of Schubert’s achingly poignant Fantasie in F Minor which was somehow just as shattering in its entirely different way. The intimate concert seemed to transport David utterly.

As it happens, the pair repeated the two pieces a few months later, this past February, at their premiere concert at Carnegie Hall in a performance every bit as shattering and somehow, too, every bit as intimate, to ecstatic audience and critical response. (You can get a sense of their versions of both pieces by way of videos online here and here. The Rite performance at the Carnegie had been so poundingly propulsive that the piano required fifteen minutes of re-tuning during intermission. And last week the New York Times listed the concerts as one of the year’s “Best Classical Performances.“)

Samson Tsoy (b. 1988 in Kazakhstan, to a Korean father and a Russian Jewish mother) and Pavel Kolesnikov (b. 1989 in Siberia)—partners both on and off stage—first met while studying at Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Conservatory from 2007 to 2011 at which point they transplanted themselves to London, virtually penniless, in the hope of expanding their artistic horizons. Which they then proceeded to do, with startling speed, both as soloists and as a duo, both in concert and by way of recordings. (The Schubert Fantasy was featured on their first joint album on Harmonia Mundi earlier this year, along with an uncanny deconstruction of the same piece by Leonid Desyatnikov, of which more anon; and the Stravinsky Rite will be featured, along with Ravel, on another CD, due out this coming spring. Meanwhile, for instance, Kolesnikov has issued an exquisite recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, a cycle upon which he likewise collaborated on stage with the eminent Dutch dancer-choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, and Tsoy is just releasing a lyrically wafting Brahms-Busoni-Reger CD, as featured on a video single here. In addition, they have been subjects of a whole slew of print and broadcast profiles, including a particularly affecting one on BBC television.)

A recent commission from Gagosian Quarterly afforded me the happy chance to talk to the pair about all of that, but especially about the singular manner in which they have been breaking free of the traditional strictures of classical performance by way of the marvelously various series of cross-disciplinary experimentations, encompassing dance, architecture, literature and especially the visual arts (braiding their music with heroes both living and dead), that has come to characterize their steadily burgeoning careers. A condensed version of that conversation indeed appeared in last month’s issue of the Gagosian Quarterly. Here follows a somewhat amplified director’s cut.

*

Lawrence Weschler: When I think about your collaborations with visual artists, it reminds me of the Cubists working with Russian dancers, Chagall with the theater, and so forth. Were there any collaborations of that sort taking place during the time you spent at the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory, from 2007 until 2012?

Samson Tsoy: I don’t think the early 2000s in Moscow can be compared with the beginning of the 20th century. Our impression is that culturally, Moscow was partly in the process of catching up with the West, partly still not fully aware of it. There was mainstream, academic culture, at times remarkable, at times rather dusty. And there were niche projects, both very avant garde and naive. We arrived as outsiders from the provinces and entered the illustrious but conservative school. We spent those few years in Moscow mostly honing the “athletic” skills of piano playing, for which it was possibly the best place in the world.

LW: Did you visit many museums during the time you were at the conservatory?

Pavel Kolesnikov: In those years I went to the Pushkin Museum regularly, particularly for the 20th century collection. That’s where I saw my first Matisses, first Rembrandts. We went to other places occasionally but, looking back, I am actually surprised and a bit regretful at how little we saw. We were working really hard in those years, it was extremely competitive—and, quite simply, we hardly had any free time.

ST: The Pushkin Museum has an incredible collection. There was a J.M.W. Turner exhibition that came to Moscow in 2008 which was a really big deal. We got permission to skip a lecture from our music history professor and went there. It was almost impossible to get in. The line was going all the way around the huge building—we had to queue outside for hours and hours in freezing Russian winter. It was incredibly exciting—the sense of a truly important event, something rare to experience nowadays.

PK: That museum was also appealing for us because of its association with the pianist Sviatoslav Richter, a somewhat godlike figure for us in those times.

A very great and profoundly original artist, I believe he is peculiarly misunderstood as a representative of mainstream Soviet culture—whereas he was in fact the most decidedly non-Soviet musician of his entire generation! Making a proper acquaintance with what Richter was about was a revelation. Perhaps, the best way to describe the “Richter-phenomenon” is to say that he was a bearer of a rare condition that doesn’t allow one to differentiate between “life” and “art.” He lived in a complex flux where artworks were treated as live beings—and perhaps, vice versa. Imagine a world where works of music and visual arts, nature, ideas, people, landscapes—all belong in the same category and can link with each other completely freely. That, in my understanding, is the world of Richter.

ST: Traditional education tends to separate art forms: we study music, or writing, or visual arts. But artists exist in a dialogue with each other and with the world out there. The medium you are using might be different, but connections work in a similar way: the brain and spirit work in a similar way. When I watch younger musicians training, they focus on six, seven hours of playing piano, and the connection gets lost, there is no time for it. But we always sought out that connection.

The same happens in other art forms, of course. Take ballet, for instance, which I adore. It's breathtaking when the dancers manage to get outside of their world. But of course they have to spend so much time working on their very own notions that then, as a spectator, one often ends up feeling like a mirror, a mirror in a dance class.

PK: The way each art form is defined in what it is supposed to do or not do is hugely artificial. For instance, as performers of classical music we should have the full freedom and even responsibility to define the limits of our work and how it is positioned, and there is no law there except some applicable laws of physics.

There are some well-established bridges between different art forms where they cross into each other’s territory. Those zones are mysterious and hugely interesting, and they can provide you with a lot of vital information. I am thinking, for instance, about the way classical (functional) harmony somehow mirrors figurativism in the visual arts, or about how the non-verbal syntax of music is as close to literary syntax as it is to the syntax of dance. So that for me, for example, it is much better and easier to learn about form in music by studying photography or painting.

LW: My grandfather was a composer, the Weimar émigré Ernst Toch, and he would often speak about the architectonic in music, which is to say architecture across time rather than space.

PK: Yes, architecture is another area that more than borders with music—not only in technical aspects, but also psychological. As a performing artist working mostly with existing pieces of music, I sometimes approach a piece as an inhabitable space—a house that one person after another fills with their very own dreams and fears.

LW: My grandfather sometimes preferred reading scores rather than listening to recordings of music. I was always mystified by that. Was he hearing his own version of the music in his head? Was there, I wonder, a somehow purer version that he could only attain by reading it?

ST: Sometimes we work without the instrument, we look at the score and do the work in our imagination. For a practicing performer, it is an important moment in the working process. You do get to focus on things that might get lost in the physicality of the process of playing. You need to try every possible route, but in the end it is a very fine balance.

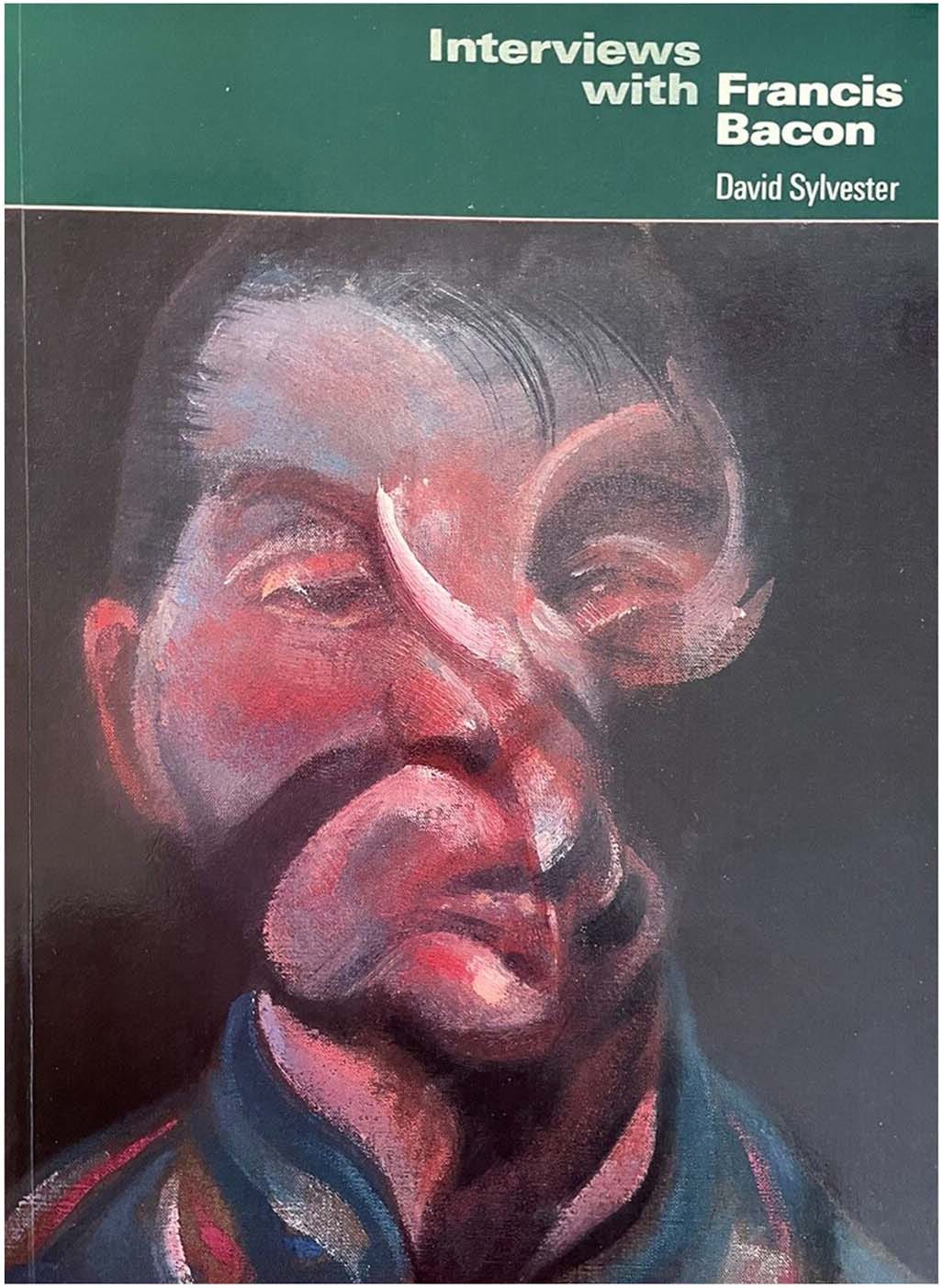

PK: Some years ago, I stumbled upon the book of conversations between Francis Bacon and David Sylvester. I couldn’t believe it: the whole book is a kind of a manual that is more applicable to music-making than many books I’ve read about music.

Bacon speaks beautifully about the physicality, the materiality of paint, about the need to know how to follow it. Now, the fact that sound is intangible and invisible doesn’t make it more flexible. You cannot just bend it any way you want, because it is no less stubborn and unyielding a material than wood and steel, the two materials as it happens that a modern piano is actually mostly made out of. You put a lot of effort into working it, but sometimes you need to obey and follow it. And it’s never something like what you have imagined.

LW: When did your own collaborations with artists start, and how did they come about?

ST: When we first came to London in 2011 we rented a small garden flat in an interesting house. Our landlord turned out to be Antoni Malinowski, a very remarkable Polish artist. And over the years, slowly, he became a really important influence, both on a personal and an artistic level.

PK: At that point, there was an interesting collaboration going on if we can call it that: Our piano was located below his kitchen, which was below his studio. Only after a few years of living there did we we find out that Antoni liked to go upstairs and paint while we were working at the piano. The sounds rising through the structure of the house were reaching his studio like vapors or flames and he found them beneficial and stimulating for his work.

ST: We would visit his studio and see the completed works or works in progress, but we never saw the painting process itself.

LW: You were seeing how he was composing his work.

ST: Yes, exactly. And then, the fluidity and precision of his work was also infiltrating ours. This sly exchange was going on for years.

In 2019 we started the Ragged Music Festival which we wanted to become something of a sheltered playground where we could try out things that would be difficult to realize at mainstream concert venues. We started it at the Ragged School Museum in Mile End, in East London. This is a place with interesting energy—a survivor, a shard, an outcast. We were keen to work with the spirit—to try and find some specific resonance between music and space.

PK: Our first experiment was purely musical. Then Covid came, and we did two more festivals between the lockdowns there that suddenly acquired a deeper significance. The communal act of live performance was being undercut in those days by the complex choice between safety and danger, between body and spirit. There was a lot of talk about open windows and ventilation. For example, we found a way to work with Antoni. He made a large wall painting, an incredible, mystical thing. It was at the back of the auditorium, on a partition that was blocking the windows.

It was a kind trompe-l’œil painting with a lot of black on black, that played with the idea of doors and windows. It had a huge presence in the room, both looming and inviting, seductive perhaps. It threw that room completely out of balance, and the audience that was mostly seated with their backs to it was always aware of the shimmering abyss behind. As musicians, we were facing it while playing and we felt we could bounce every piece and every idea against it. It was about illusions and hope…

ST: …and the sadness and darkness in that. He painted it knowing that it would be destroyed because the school was being renovated. He painted it just for that moment, and it created the uniqueness of the moment, and its fragility. We built our whole festival around that feeling.

LW: What did you perform?

ST: It was in May but we centered our program around Schubert’s Winterreise, a chilling tale of self-loss and self-destruction. Its counterpart was Bach’s luminous Goldberg Variations. The whole program with Beethoven’s Große Fuge and Spring Sonata, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata and many other works oscillated between blazing sunlight ahead and the darkness of the black “thing” behind, sometimes mixing them together.

LW: It seems to me that you have the entire repertoire of piano and chamber music at your fingertips and that you deploy it the way a painter deploys paint.

PK: Performers these days often compose their own works. Sometimes we do. But when we perform existing works they change drastically (or rather, we can adapt them drastically) depending on the physical context, not only because of acoustics but because of the visual effect of the place.

ST: And our interpretation changes depending on what message we want to transmit to our listeners. It also has great fluidity which comes from the exchange with the current energy of the audience.

PK: But most interestingly, when you put one piece next to another, there is a conversation that emerges between them. In the same way as there can be an interaction between visual artworks. The only difference is that music develops over time. You experience musical works one after another. But there is constant stream of memory that captures everything. And that memory creates a very powerful—

LW: Afterimage, as it were.

PK: Yes, which adds layers, one over another, to an extraordinary effect. This is a process of building narrative—like theatre, except music is inherently abstract. We recently had a conversation with Bridget Riley about that.

LW: How so?

PK: We met her after one of our concerts. She mentioned appreciating that music didn’t need to fight against figuration, it didn’t deal with figuration, and that was making the work much “freer”. I was amazed to hear her saying that—I had such thoughts on my mind for so long!

ST: She also said that she has been learning many things about her art form through music. She brings in new ideas that have purer expression in music.

LW: Indeed: Her work often has the feel of a vibrating string.

ST: Yes, and if you let some of her paintings move and vibrate, not trying to control them, you will eventually experience something that is like a sound hallucination, a visual illusion of a sound, a miracle of incarnation.

LW: Robert Irwin used to talk about site-specific work, how he would always make a different piece depending on the site. Later in his career, it wasn’t just site-specific, he said, but site-conditioned, that the conditions of the particular place and time and surround dictated through him the response. In a sense you are talking about site-conditioned programming.

PK: Yes…one begins with something site-specific and then it becomes site-conditioned. Music has this unique ability to be specific to the place and moment, infinitely.

LW: Infinitely specific. That’s really perfect. Specific is finite by definition—that’s almost a Kierkegaardian way of talking about the perpendicular intersection of the divine with the temporal.

PK: I should probably write that down. [laughter]

LW: Recently, though, Pavel, you did a project about Joseph Cornell and his Celestial Navigation.

PK: I discovered Cornell’s work when I was in my early twenties. He has become one of the most important and inspiring artists for me. This principle of confining things together and making them work out the ways they “shift.” Of course you need to do it very carefully, but there are so many possibilities that open up just by putting things together in a box. As performing artists, we often work within a box—a concert stage with the proscenium and a piano. One day I thought that it would be interesting to construct a recital based on the same principles. It was not biographical in any way—it was linked to Cornell, but not about him. It was just this thing of putting things together.

I decided to make a pair of “boxes” that would together form a recital. The first was assembled in collaboration with the architect Sophie Hicks who made an abstract film to do with water and celestial bodies that was aligned with music. It was projected on the back wall on the stage—something of a Narnian wardrobe, opening up the space inside into a lyrical, nocturnal void, eventually fading and disappearing into absolute darkness.

The other one was much more austere—more like one of Cornell’s Dovecote boxes. I asked Martin Crimp, the playwright, to write four short dialogues, one for each of the Schubert Impromptus Op.142. And Martin had an idea to construct them from found material. He’d discovered a conversation book for travelers from England to Austria that had been published in the eighteenth century. He picked a few dialogues from there which were incredible—mundane, poetic, and totally surreal. They made such a strong impact that at some point we had to decide if it wasn’t too powerful. They were projected on the wall before each piece, kind of as inter-titles in a silent movie.

ST: I was there as a listener, as a spectator. To amplify the effect, you placed yourself sitting with your back to the listeners, facing the wall in front so you too could read them and take a momentary inspiration or a cue from them.

PK: Yes, that performance was a very time-and-site-specific thing. It was in a brick barn turned into an amazing concert hall, in the countryside in Suffolk. It was incredible because the audience behind me was reacting to the text. And then I had to react to the text and play the music that was already there. The whole idea was prompted by one of my most favorite works of Cornell—a collage called Where does the sun go at night?

There are two birds in a landscape speaking to each other, by way of dialogue bubbles—only the bubbles are empty, black in one case, yellow in the other. It is incredible to witness how omission of text in them allows a totally nonverbal, inexpressible meaning to take over.

In our joint experiment with Martin we did the opposite—removed the image, letting it be replaced by non-visual void of music. It was like a glance into a different dimension.

LW: Robert Irwin used to say that Malevich made an absolutely extraordinary revision of the Cartesian claim of “I think, therefore I am.” He said that Malevich said “I feel, therefore I think, therefore I am.” And when Malevich painted white on white and people said, “You’ve taken everything away from us,”

Malevich’s reply was, “Yes, but I brought you to a desert of pure feeling.”

PK: That’s wonderful, I didn’t know that.

ST: That’s very good.

LW: Pavel, in Bilbao you performed John Cage’s 4’33” and afterwards, you said that was one of the most difficult performances you had ever done. Why would that have been so difficult?

PK: The piece doesn’t contain any notes, it is just a duration, it’s a pause that is supposed to last four minutes and thirty-three seconds. And that is actually a very long time. It is one of the greatest pieces of music, and it opens up a Pandora’s box—all the questions about what music is, and what performance is, and what art is. It’s one of the most universal artworks out there. In my opinion, it is even stronger than Malevich!

This is also the one and only piece of music that you cannot rehearse in any way. As a performer you’re not used to this situation. In this case I faced the audience, which is something as a pianist you typically…

ST: ...never do.

LW: That piece is about the chance sounds all around and inviting the audience to become incredibly conscious of them. But I’d never really thought about the volcanic experience of being onstage: You’re just there and everybody’s looking at you.

PK: Of course, I was aware that it was about listening to everything that is happening in the hall or onstage. But as the performer, I found out that was actually not the main part. It was about putting myself and others in an incredibly contained situation where there was no escape.

LW: Great pressure.

PK: You have to be there for this amount of time, no matter what happens. In fact, you are bound to be there because an unfinished performance of 4’33” cannot exist! Once you enter the “contract,” a commitment to four minutes and thirty-three seconds, you really cannot break it, even if you leave the stage, or die. And it’s an incredible amount of pressure that comes both from within and outside.

ST: For the listener it’s also very uncomfortable. Everyone feels the tension. Everyone is suspended. It also creates space. Because everyone is tied together by this absence of sound, by a great communal pause.

LW: There was also a show at the Guggenheim in Bilbao of Pop Art and you, Pavel, were asked to create a program.

PK: By coincidence, before I received that invitation I had been already playing with the idea of a Pop Art musical program and I came to a conclusion that there was no art movement that was more unmusical, particularly with regard to the work of Andy Warhol. But a good challenge is always my weakness! It took me a very, very long time to figure out a way—I was becoming really desperate. But eventually I thought, “Let me see if I can apply the core principles of the movement, how I understand them, and see what happens.” I made a Google search for the most famous pieces for piano. There was a list of all those really famous pieces, and it was fascinating for two reasons. One is that no one would be able to explain why they are so popular. And the other: they are so well known that they have actually sort of become invisible—or rather, inaudible. One hears them all the time but one cannot hear them.

LW: Some examples?

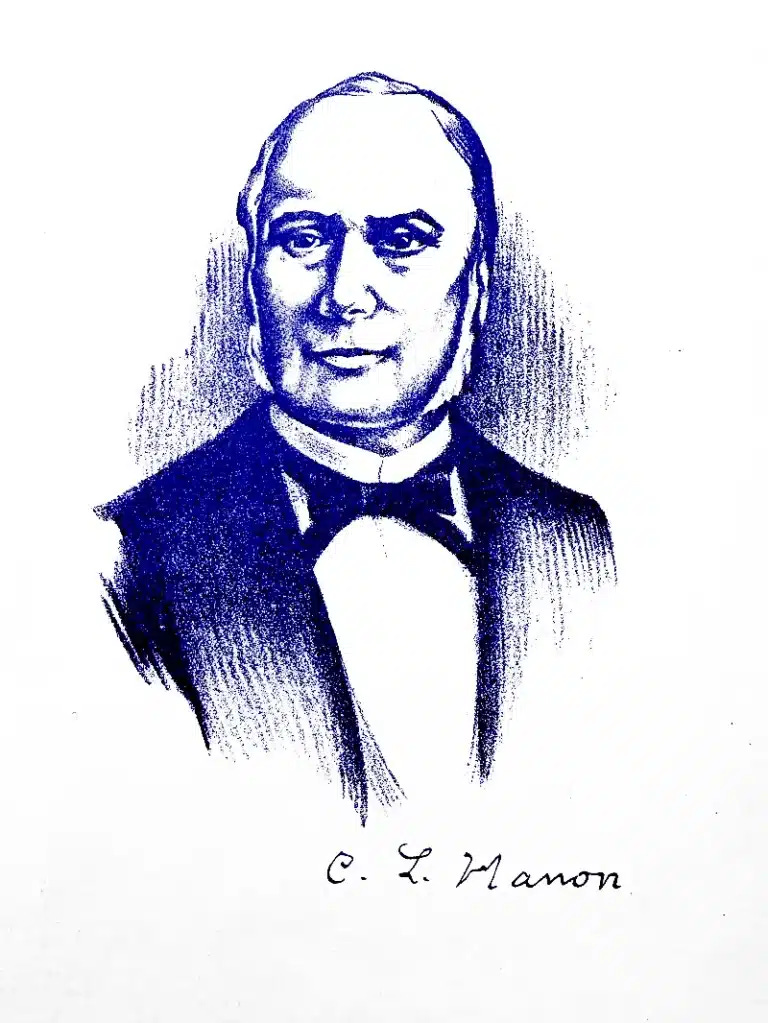

PK: Moonlight Sonata, Mozart’s C Major Sonata Facile, Debussy’s Claire de Lune, etc. Those are musical objects which have been rendered completely opaque by their ultimate familiarity. So I used those pieces to make funny constructions, sort of balanced so that they are too serious to be a joke and too silly to be a real thing. And played them on a loop. And I came up with this idea of in addition playing French exercises by Charles-Louis Hanon.

LW: These are scales?

PK: They’re not scales exactly, but they’re 19th century exercises for finger dexterity. They’re based on scales and arpeggios, and they just go through all the tones of the octave: moving first upwards and then back to the bass. These are the most basic exercises out there, there is nothing “musical” in them, they are just purely functional. And of course they are never treated as artwork. Throughout the history of music, they have never been performed on stage, I am absolutely sure about that!

But of course, they sound absolutely stunning, insanely cool when you put them in a stage situation. So this is what I did. I played them in octave, in 5th and 9th and also on black keys repeatedly throughout the program. It was joyful, perplexing and very pure—pure fun!

LW: Samson, for your part, you performed the Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time surrounded by a Richard Serra sculpture.

ST: Yes, inside Serra’s Transmitter at the Gagosian-Le Bourget, in the autumn of 2021, I went to Paris to see the work and the space. I walked through the Transmitter and around it, and inspected it from the gallery above.

To me Serra's work is often testing the boundaries of possible and impossible. It creates what may seem an anomaly but in fact is the opposite: it just brings “true” experience into focus. Serra was an artist who understands space, deeply. Here, I also had to find a way of making sense of this very complex space, both spatially and acoustically, to find a way to articulate it with sound and create a fluid exchange between the sculpture, music, and the audience.

I found that the emotional response was changing drastically depending on where I was in relation to the work. Literally, every corner of that space felt different. Most strikingly, while the work is incredibly imposing from the distance, the closer you get to it, the more you experience its warmth, intimacy, subtlety, and even fragility.

PK: It is incredible to witness how, in spite of the scale (indeed, perhaps, thanks to it!), the experience easily shifts to subtle things—light, touch, sound. The way sound travels and changes in those sculptures is quite extraordinary.

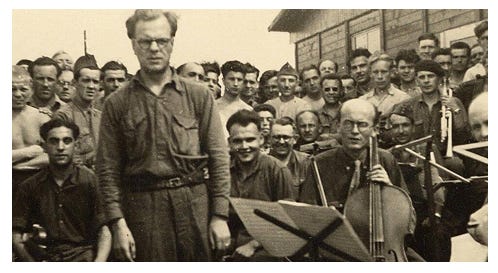

ST: There is one more dimension that is actively at play in Serra’s work, which is to say time, which becomes strangely tangible. In that somewhat apocalyptic moment, feeling like prisoners of Covid, many of us experienced a certain thickening of time, becoming more aware of it. Emotionally, during those days I felt very connected to Olivier Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time. The piece was composed in the prisoner-of-war camp in Görlitz in 1940-41.

This is a time-, place-, and means-specific work which was written for a formation of four musicians who happened to be held captive there. Instruments would engage with each other, sometimes playing all together and sometimes in dialogues, or solo “revelations.” At some point, I began to feel how these two works, Messiaen’s and Serra’s, started nearing each other, until in my mind they completely merged. I decided to engage the entire space of the sculpture for the performance, and asked Alina Ibragimova and Mario Brunello to play solo movements from Bach’s violin and cello suites in different parts of the sculpture. Then, together with Nicolas Baldeyrou, the four of us played the Messiaen's piece at the entry—or the exit, depending where you start your journey—of the Transmitter.

LW: Could the listeners move around themselves or they were in seats?

ST: People were sitting on the floor, staircase, balcony, inside the sculpture. They were completely free to choose how and where to experience the music. Some were following the musicians, some sat down, others were walking quietly and observing the changes of sound, of the resonance.

LW: It must have been amazing.

ST: The space and the sculpture profoundly influenced the interpretation. You listen to how the sound unfolds and reflects, and sense the feedback from the artwork. Time becomes fluid and flexible, constraints disappear, you gain creative freedom that is not possible in a concert hall.

LW: It is such an appropriate response to Serra and how musical his work is.

ST: Serra spoke beautifully about intervals in space. And I think this concept is one of the most fundamentally important in music, even though it somehow often remains “invisible.” We work with notes and sounds, but as importantly, with the silences in between them.

And this autumn, I will be continuing my work with or within Serra's work, The Matter of Time, at the Guggenheim Bilbao.

{ As indeed Samson did, performing pieces by Bach and Beethoven (“both composers likewise achieving this blending of the monumental and the intimate”) on the occasion of what would have been the late Richard Serra’s 86th birthday. Here’s another vantage: }

LW: You two also have that new CD just out where the two of you perform together, with four hands on one piano. It includes that Schubert Fantasie you played both at David Hockney’s and at Carnegie Hall, and also a piece by Leonid Desyatnikov called Trompe l’œil, which is very interesting in the context of this conversation.

ST: Our challenge to Desyatnikov in the context of this commission was for him to do something in relation to Schubert’s Fantasy, that we could subsequently play in the same concert. And he recalled a trip to Milan where he saw the Santa Maria presso San Satiro, which is just off the main Cathedral—there’s a tiny chapel on the outside. When you walk inside it seems huge, because there is a trompe l’œil painting on the back wall. The great fifteenth-century architect Donato Bramante, who also collaborated with Michelangelo on St. Peter’s, had been given this tiny space and told, “Make something grand here.” And with the trompe l’œil you walk in and think there’s a huge space but when you walk towards the back, it’s suddenly not there at all.

And Leonid wondered, What would it be like to do a trompe l’œil piece in music?

PK: I often wonder how does a painter create a trompe l’œil? What exactly does it entail? What is a technique of superimposing images from different planes in one work, in one’s mind? When we were working on Trompe l’œil, we were facing the same strange conundrum. In fact, we only properly heard it when we listened back to the recording while being in the studio. Before that it was always a game of trying to come close and work on the detail but at the same time pulling back and seeing the whole. You’re never able to properly embrace the whole thing.

ST: It was a really strange process of working on something as purely musical as an audio album that was so visual, even if only metaphorically. We found ourselves constantly operating in extra-musical terms. The whole album became a triangulation of reflections, a mirror chamber. In there, the relationship between the Desyatnikov piece and the two Schubert works became very real, visible. But also it was like a de-incarnation of the image.

LW: And a desert of pure feeling! [laughs]

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

NOTE: We’ll be taking next week off. You people have a wonderful holiday. See you on the other side.

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

Amazing resonances. Speaking of piano exercises, I have to mention this snippet from the article accompanying the nyt yacht rock playlist, which just published earlier this week.

When the L.A. band Ambrosia was opening for the Doobie Brothers on a late 1970s tour, (Michael) McDonald gave the frontman David Pack some songwriting advice: If you’re looking for some really out-there chord progressions, check out George Frideric Handel’s practice books. Pack took note and soon after came up with the foundation of this dreamy 1980 tune (biggest part of me), which would become one of the band’s biggest hits.