WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

And so we’ve finally reached the concluding entry in our five-part All That is Solid taxonomical investigation of the convergent impulse, or maybe rather temper, or should we say tendency, or (as some of you may have begun to imagine) just plain delirium. This being the long-promised section where the entire exercise begins to meld into a unified field theory of cultural transmission and maybe even a stab at a definition of culture itself. But first, some further thoughts on the unfolding disaster in Ukraine.

* * *

DETERMINING THE TRUE NAME FOR THINGS IN UKRAINE

Some of you may have been seeing this inspired image flitting about the internet recently, perhaps not quite comprehendingly:

It depicts a group of Ukrainian soldiers who recently took a few minutes away from the roiling front line to restage a conclave that would be instantaneously recognizable to anyone in Ukraine, or for that matter in any lands of the former Russian empire. The reference is to a celebrated historical painting from the late nineteenth century, which in turn had reimagined a legendary event of the late-seventeenth.

With the help of the good people over at the imgur weblog, we can decipher things as follows:

In 1891, the Russian nationalist-realist painter Ilya Repin (born, as it happens, in Ukraine, of Russian military-settler parents) completed a giant canvas, over a decade in the making, depicting a legendary event (mentioned in passing in Taras Bulba, Nikolai Gogol’s romantic-historical novella of 1842)—The Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed IV of the Ottoman Empire, also known as The Cossacks of Saporog Are Drafting a Manifesto. (As his models, Repin had drawn on identifiable friends of his who were by turns Cossacks, Ukrainians, and Poles.)

The incident behind the painting: At one point, in 1676, the Cossacks of the Zaporozhian Host, inhabitants of the lands around the lower Dnieper River in Ukraine, had defeated Ottoman Turkish forces in battle. Whereupon (what’s the Turkish word for chutzpah?), the Sultan sent the Cossack band an ultimatum, demanding that they submit to his rule, to wit:

Sultan Mehmed IV to the Zaporozhian Cossacks:

As the Sultan; son of Muhammad; brother of the sun and moon; grandson and viceroy of God; ruler of the kingdoms of Macedonia, Babylon, Jerusalem, Upper and Lower Egypt; emperor of emperors; sovereign of sovereigns; extraordinary knight, never defeated; steadfast guardian of the tomb of Jesus Christ; trustee chosen by God Himself; the hope and comfort of Muslims; confounder and great defender of Christians – I command you, the Zaporozhian Cossacks, to submit to me voluntarily and without any resistance, and to desist from troubling me with your attacks.

In response, the Cossack chieftain, Ivan Sirko, gathered his troops about him to help draft a reply—the moment captured in the painting—which they eventually dispatched, as follows:

Zaporozhian Cossacks to the Turkish Sultan!

O sultan, Turkish devil and damned devil's kith and kin, secretary to Lucifer himself. What the devil kind of knight are you, that can't slay a hedgehog with your naked ass? The devil excretes, and your army eats. You will not, you son of a bitch, make subjects of Christian sons; we've no fear of your army, by land and by sea we will battle with thee, fuck your mother. You Babylonian scullion, Macedonian wheelwright, brewer of Jerusalem, goat-fucker of Alexandria, swineherd of Greater and Lesser Egypt, pig of Armenia, Podolian thief, catamite of Tartary, hangman of Kamyanets, and fool of all the world and underworld, an idiot before God, grandson of the Serpent, and the crick in our dick. Pig's snout, mare's ass, slaughterhouse cur, unchristened brow, screw your own mother! So the Zaporozhians declare, you lowlife. You won't even be herding pigs for the Christians. Now we'll conclude, for we don't know the date and don't own a calendar; the moon's in the sky, the year with the Lord, the day's the same over here as it is over there; for this kiss our ass!

Koshovyi Otaman Ivan Sirko, with the whole Zaporozhian Host.

The resultant painting so tickled the Tsar Alexander III’s fancy that he bought it for his own collection, and today it occupies pride of place in the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. Of course, a good part of the genius of this current batch of Ukrainian soldiers is that they’ve flipped the referents, realizing in the historical antecedent precisely the tone that ought to be used in addressing the contemporary would-be tsar. Take that, State Russian Museum!

Such deliciously satisfying over-the-top rhetoric, on the other hand, may in fact occlude one of the most urgent requirements of the years ahead. Shifting registers, it is important to note how on top of all the material reconstruction that will be needed in the coming period, no matter how the war turns out, there will perhaps be an even greater need for a more radically redemptive process yet, that of finding the true name for things in the wake of all this devastation. In that context, it might be better to look back upon a cultural treasure from the mid-twentieth century, immediately after the end of the Second World War,

which is to say the seminal poem “In the Middle of Life” by the sublime Polish poet (yet another one!) Tadeusz Róźewicz (translated by Czesław Miłosz):

After the end of the world

after my death

I found myself in the middle of life

I created myself

constructed life

people animals landscapesthis is a table I was saying

this is a table

on the table are lying bread a knife

the knife serves to cut the bread

people nourish themselves with breadone should love man

I was learning by night and day

what should one love

I answered manthis is a window I was saying

this is a window

beyond the window is a garden

in the garden I see an apple treethe apple tree blossoms

the blossoms fall off

the fruits take form

they ripen my father is picking up an apple

that man who is picking up an apple

is my father

I was sitting on the threshold of the housethat old woman who

is pulling a goat on a rope

is more necessary

and more precious

than the seven wonders of the world

whoever thinks and feels

that she is not necessary

he is guilty of genocidethis is a man

this is a tree this is breadpeople nourish themselves in order to live

I was repeating to myself

human life is important

human life has great importance

the value of life

surpasses the value of all the objects

which man has made

man is a great treasure

I was repeating stubbornlythis water I was saying

I was stroking the waves with my hand

and conversing with the river

water I said

good water

this is Ithe man talked to the water

talked to the moon

to the flowers to the rain

he talked to the earth

to the birds

to the sky

the sky was silent

the earth was silent

if he heard a voice

which flowed

from the earth from the water from the sky

it was the voice of another man

The Ukrainians, for their part, might already have begun that originary task—that of rediscovering or else reinventing the true name for things—or so Yale historian Timothy Snyder recently suggested in a piece for the New York Times Magazine, available here. Of course, that is not a task that will need to be confined to them. The Russians will be requiring some of the same, and frankly, so do we.

* * *

This Issue’s Main Event:

All That is Solid:

Toward a Taxonomy of Convergences & A Unified Field Theory of Cultural Transmission

PART FIVE (The Finale)

Last time out I began with a recap of this entire All That is Solid exercise, at least up to that point, and those feeling the need for that sort of refresher course might wish to refer back to that. We then explored the way that convergent effects (disparate things looking or sounding or seeming uncannily alike) could sometimes be accounted for by way of lineages of Direct Influence—which is to say one artist’s generalized impact on the next, either forward or backward, conscious or unconscious. After surveying several categories of that sort of thing, we launched into a consideration of an entirely new category, that of Allusion, where a successor artist consciously references a prior master, starting with Invocation—the way, for example, that Rembrandt in his Anatomy Lesson seemed to be conspicuously alluding to Matagna’s Lamentation of the Dead Christ, or how Manet was regularly doing likewise with Goya. But the Allusive tendency can take other forms as well, including

Homage

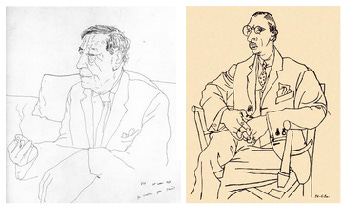

Artists invoke the works of earlier artists; they pay homage to the artists themselves. Thus once again the example of David Hockney, who while he never seems to mention Matisse (see Anxiety of Influence in the previous issue ), at the same time never seems to tire of alluding to Picasso, his grand master and perpetual touchstone. The acknowledgment was there almost from the start with the young Hockney in 1973 imagining himself posing nude across from the older Picasso;

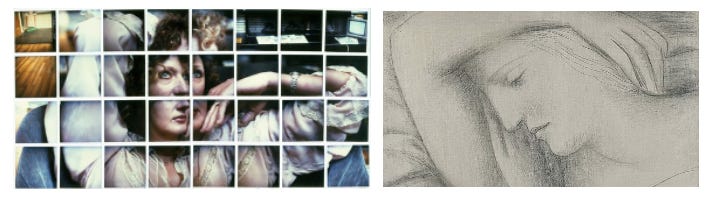

and it’s been there in the form of conspicuous allusions throughout (Hockney’s Auden echoing the pose of Picasso’s Stravinsky, and Hockney’s Celia likewise summoning the sensuous languor of Picasso’s Marie-Therese);

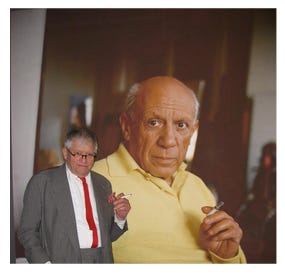

and more recently Hockney has even been happy to draw on the authority of the Old Man in his often over-the-top defense of smoking.

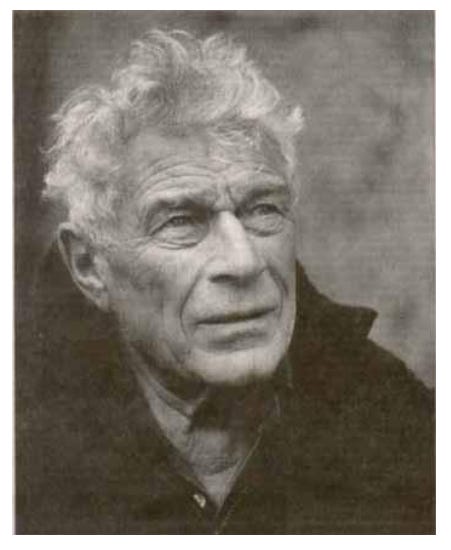

Meanwhile I suppose this is as good a spot as any to acknowledge how this entire taxonomic exercise of mine takes place as a humble act of homage to my own (unwitting) late master, John Berger.

Now, allusive instances aren’t always quite so portentous. For example, they can often take the form of

Puns

as in 2004’s Spiderman 2, where, in that sequence in which our hero singlehandedly brings a runaway train to a grinding halt, audiences couldn’t help but notice that they’d somehow suddenly fallen into a sort of arachnid version of the Passion—

a passage (see the actual clip here) in which director Sam Rami himself seemed to be bowing in homage to Robert Altman, whose 1970 M*A*S*H featured an earlier version of virtually the same antic gambit, as characters at that Korean War mobile hospital unit seemed momentarily to align themselves into a dead ringer imitation of Leonardo’s Last Supper.

For the actual clip see here. (For that matter, this would likely be as good a place as any to file our Cossack-channeling Ukrainians referenced above.)

Pastiche

While puns tend to play out in momentary flashes of wit across a wider artistic project, pastiches, wherein one artist openly imitates an earlier precursor, often to similarly satiric effect, tend to constitute complete works in and of themselves. Thus, for example, the ad for a department store sale I came upon a while back during a trip to Madrid on the back page of a local throwaway magazine which conspicuously referenced the greatest painting in that city’s greatest museum, the Prado’s Las Meninas by Velasquez:

Though, as often happens with pastiches for some reason, the copy helps reveal some of the deeper splendors couched inside the original. Note how in the ad a photographer dandy stands in at the same spot occupied by the painter Velasquez in the painting, apparently gazing intently along with the rest of his crew of costumed models into their own reflections in a wide-facing mirror, camera at his waist, getting set to snap the very image we now see before us. Such, at first blush, appears to be the narrative conceit of the Velasquez painting as well—but in the case of the painting, things quickly become more complicated. For one thing, if that silvered rectangle behind and to the painter’s left in fact contains, as it appears to, a mirrored reflection of the king and queen,

then in fact we are being invited to inhabit their point of view as they happen to have happened upon the court painter busily in the act of rendering a group portrait of their daughter, the Infanta, flanked by her variously attentive retinue.

But wait a second, that can’t be right. For one thing, maybe that silvered rectangle is no mirror at all but rather an earlier painting of the royal couple (I mean, obviously it is a painting of the royal couple, a localized slather of pigmented muds spread over a portion of the wider canvas). Because the fiction of the painting further implies that what the painter is looking into is in fact, as with the photographer, a mirrored reflection of the scene beside him, which he is in the process of rendering onto that huge canvas angled over to (our) left side of the painting, a canvas which, come to think of it, must be the very painting we are now looking at. (Though maybe the reflection is reflecting a giant portrait of the king and queen who are in fact posing in front of him).

Though wait another second, nor can any of those be right. Because that’s not how painting works. That’s one of the important ways in which painting is different from chemical photography (photography which, remember, didn’t exist during Velasquez’s time, even notionally). In fact as he was painting Las Meninas, Velasquez would have been standing more or less where we as viewers now stand looking at the painting, and more to the point, the scene before us would never have been a scene before him (or at any rate never have needed to be). Rather, during the months and months of the painting’s composition, Velasquez might have spent a few days working on the dog, and then another few days laying in the prince over to the dog’s side, the boy teasing the endlessly-put-upon dog with that little kick, and during those days, the prince (or more likely his stand-in—and on second thought, might that be a court midget rather than a princeling?) would doubtless have been leaning on some sort of foot stool and not onto the dog’s flank; if nothing else, the actual dog would not actually have sat endlessly still for such tomfoolery). A whole other sequence of days would have been devoted to the Infanta’s dwarf, and I doubt the Infanta would have stood still for that. And so forth. Furthermore, anyone viewing the finished picture at the time of its completion would have known that’s how it was made—and hence known how to read it, as a composition unfurling across time. It’s only we, living in the wake of the invention and subsequent rampant spread of photography, who are saddled with the fantasy of the immediate, the very fantasy incarnated in that pastiche department store ad. (Now, I’m hardly the first person to have become entrammeled by the enigmatic vantages embodied in Velasquez’s masterpiece—consider for example Foucault’s famous treatment of some of these same perplexities near the outset of The Order of Things —I just happen to have been lucky enough to have happened upon that department store ad pastiche as an occasion for further thought-bending.)

The same sort of perceptions can arise out of a consideration of contemporary photographer David La Chappelle’s recent pastiche tribute to seventeenth-century Dutch floral paintings. (Almost impossible to tell them apart, except note the gleaming cell phone at the bottom of La Chappelle’s rendering.) Now, La Chappelle had to gather together flowers at various stages of decomposition for his instantaneous photo shot.

That is unless—as nowadays is becoming more and more often the case—he Photoshopped the final image, layering in one flower one day and another the next, in which case he would have been engaged in an activity much closer to that of his seventeenth century predecessor. (David Hockney has lately been commenting on the fact that, what with the rampant recent spread of Photoshop over the past couple decades, for the first time since 1839 the hand of the photographer is re-entering the frame and the often quite gaping 150-year divide between painting and photography is thus rapidly beginning to close back up.) The point at any rate is that during the seventeenth century, painters never actually attempted to portray a fully-brimming floral arrangement along the lines of the one ultimately offered forth in their finished painting (such an actual bouquet would long have wilted to compost before they could have finished their rendition). Rather, like Velasquez, they slowly built up their burgeoning still life one blossom, one bulb, one branch at a time, all the while layering in ever deeper significations (all those creepy crawlers and flitting flyers, for more on which, see the late Harry Berger Jr.’s positively revelatory 2012 monograph, Caterpillage, wherein the good professor suggests that contrary to their placid pastoral reputations, such paintings may afford some of the most violently roiling depictions of, and occasions for, meditation on such mortal violence that any visitors nowadays are likely to encounter during their museum walks).

So much for the higher potentialities of pastiche!

Parody

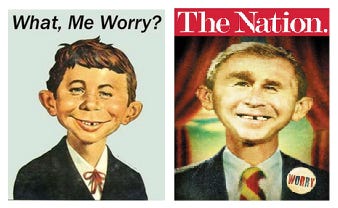

Which brings us to one final subcategory of the Allusive-Antic, the sort of thing one regularly finds among practitioners of the fine art of political hijinx (as for example, here too, our Cossack-channeling Ukrainians). Or, to take another instance, when the editors of The Nation noticed that goofy-grinned George Bush (the younger) bore a startling likeness to Alfred E (“What, me worry?”) Newman, the longtime mascot of MAD magazine.

(There was a particular piquancy to this insight, since years earlier, commentators had noted a similarly compelling resemblance between the visages of Master Newman and Bush Junior’s father’s vice-presidential pick, Dan Quayle. Which I suppose, if nothing else, may say something about Bush Senior’s conception of son figures.)

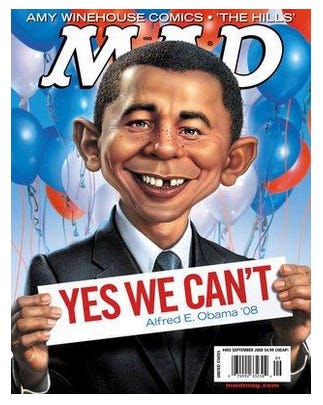

Anyway, for some reason The Nation’s cover clearly rankled Republicans, who a few years later during the candidacy of the admittedly jug-eared Obama, countered with a stinging poster of their own, fantasizing how things might look “If Obama was [sic] Republican,” and subsequently going on likewise to lampoon Shepard Fairey’s ubiquitous stylized Obama HOPE campaign posters with an offering of their own.

To no avail, alas: Obama nevertheless went on to win the election, at which point, not to be outdone, MAD magazine itself weighed in with its own inauguration cover, featuring Alfred E. Obama, in an unsettlingly spot-on premonition, holding up a bumper sticker declaring “YES WE CAN’T.”

*

QUOTATION

Can or can’t, though, we move on—into an entirely new wider category, for while artists and practitioners often allude glancingly and in passing, as it were, to the works of their much-vaunted predecessors, other times they will find themselves quoting virtually verbatim. This being the sort of thing one finds, for example, all over Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, a masterpiece which seems at times to have been composed in continual thrall to William Shakespeare and the King James version of the Bible, not to speak of all the whaling manuals with passages from which Melville is constantly larding his chronicle.

And it’s not just writers who quote almost verbatim. Consider the case of that other great canvas of Velasquez’s (completed at almost the same time as Las Meninas): The Spinners, otherwise known as The Fable of Arachne.

That’s her there in the far back center of the painting, her arms spread in astonishment.

The story goes (as I had earlier occasion to relate at one point in Everything that Rises) that so sumptuous were the tapestries the young Lydian maiden wrought that there were those who claimed she had to have gleaned her craft from the great goddess Minerva herself—a claim that Arachne, for her part, dismissed out of hand: her brilliance was all her own, the headstrong girl insisted, and was if anything greater than that of the celebrated goddess, so what could the latter have possibly taught her? Minerva (or Athena, as she was of course known to the Greeks) was hardly amused by such intemperate boasting and presently appeared before the young maiden, disguised as an old hag, to urge greater piety upon her. The proud young girl spat out her contempt at such presumptuous advice, going so far as to challenge the goddess herself, should she happen to be listening, to a direct contest, so as to settle the question once and for all. At which point, of course, the old crone instantly transmogrified into the mighty goddess, veritably doubling in size—and the race was on. As subject for her tapestry, Minerva chose to portray the primordial events surrounding the founding of her own magnificent city, Athens, and naturally she did so to dazzling effect.

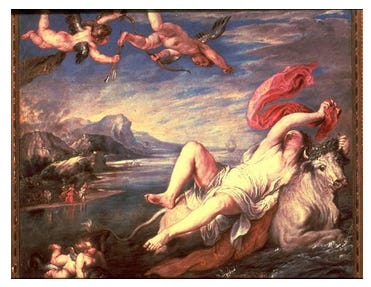

But Arachne’s efforts were no less astonishing: as her theme, she chose the abject love the gods so often come to harbor for mere mortals, braiding a garland of specific instances (Leda, Danae and so forth) around the central image of the infamous abduction of the lovely young maiden Europa by a lust-addled Jove, momentarily disguised as a bull.

At the instant portrayed in Velasquez’s painting, Athena, having failed to locate the slightest flaw in the mere mortal girl’s offering, has taken to sputtering in rage and is getting set (as was often the wont of the gods, faced with such insolent challenges) to wreak unholy vengeance by turning the protesting girl into a web-weaving spider, eternally to dangle at the end of her silk thread.

But now look at how Velasquez has chosen to portray Arachne’s woven masterpiece arrayed there behind her: A direct quote from that painting of the maiden Europa being led away into the sea by Jove in the form of a bull, as rendered by Titian,

the Venetian master from the previous century who was widely considered, during Velasquez’s lifetime, to have been the greatest painter of all time (Titian’s painting had in the meantime come to lodge in the Spanish king’s own collection, as we discussed a few issues back when considering the show at the Gardner). With his painting, though, it is as if Velasquez were boasting, “Look, not only can I offer an exact copy of Titian’s masterpiece, but I can outbest the Venetian master: see how, there in the foreground, I can render motion itself, with the spinning of the wheel, something Titian never even tried.”)

Quite a claim, when you stop to think about it, in a canvas allegorizing the hazards of boasting on the part of mere mortals. Paging Dr. Freud (or at the very least Professor Bloom).

*

APPROPRIATION

Quoting tends to be piecemeal—the source work only getting sampled in part (Melville), or even when sampled in full, as it were, only taking up a small portion of the receiving entity (Velasquez). Sometimes, though, particularly more recently, the painterly or sculptural act of quoting gets raised up a notch into something qualitatively different, a fresh gambit (featuring a virtually one-to-one transposition) whose resultant works, as it were, call for a whole separate compartment in our ongoing survey of convergent effects.

For example, Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans, which were essentially just blown-up renditions of regular Campbell’s soup cans (indeed, when challenged as to what difference, if any, there was between his painting and regular soup cans, Warhol responded by deadpanning “Well, Mr. Campbell signs his on the front.”)—though, granted, in this new context they played all sorts of coy sweet riffs on contemporary artistic practice, for instance offering a sort of sly, straight-faced Pop commentary on the transcendent aspirations claimed for the stacked floating color clouds in the paintings of Rothko’s high midperiod. Or else, what with each soup flavor represented by a separate unique canvas, the entire series offering a tongue-in-cheek contribution to the then-recent fad for serial and grid production. Still and all, the disparity in size and dimensionality might undercut the strictly appropriational claims of the exercise, and for those thus bothered, Warhol offered exact-size painted wooden boxes meticulously painted over with the red-white-and-blue Brillo pad logo.

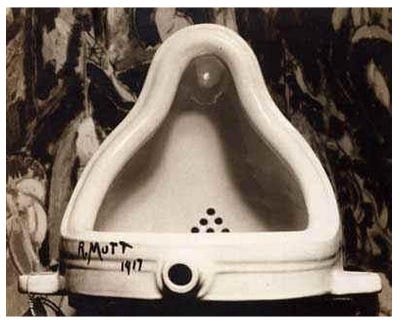

Now, of course, in broaching such appropriative gambits, Warhol was himself appropriating one of the core methodologies of the century’s virtual inventor of appropriation, Marcel Duchamp. In 1917, or so the story goes, Duchamp, flanked by his pals Joseph Stella and Walter Arensberg, marched into the J.L. Mott Ironworks on Fifth Avenue in New York City, where he bought a standard Bedforshire-model urinal, thereupon lugging the thing back to his studio, where he set the so-called ready-made on its side, signed it “R. Mutt,” titled it Fountain, deemed his day’s labor good and declared the object “art.” (There’s an alternative version of the piece’s genesis that has Duchamp himself appropriating both the gesture and the very object itself from a “female friend” who supposedly had sent it to him—speculation centers on the scatalogically inclined Dadaist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven—but we’ll set such revisionist conjecture to the side for the time being.) At any rate, Duchamp now endeavored to enter the piece into that spring’s follow-on exhibition to the Armory Show of a few years earlier, where his Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) had caused such a howling critical ruckus (“an explosion in a shingles factory”). This time, though, the show’s scandalized organizers didn’t even let the piece—after all, simply a urinal set on its side—into the exhibition.

Simply a urinal set on its side, yes, and yet so much more. “A lovely form has been revealed, freed from its functional purposes,” as Duchamp’s sidekick Arensberg insisted, appealing the board’s decision, “—therefore a man has clearly made an aesthetic contribution.” (An estimation resoundingly reaffirmed, almost a century later, when, in a poll as part of the run-up to the 2004 Turner Prize, over 500 international art experts voted it “the most influential modern art work of all time.”) To no avail at the time of its inception, however. So Arensberg and Duchamp carted the forlorn thing over to Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery (as Rachel Cohen relates in the 16th chapter of her luminous Chance Meeting braid of interweaving essays), where Stieglitz in turn photographed it in a glow of profound reverence. Carl Van Vechten subsequently enthused to Gertrude Stein, by letter, how “the photographs make it look like anything from a Madonna to a Buddha.”

Or, as I myself always thought, and, interestingly, found myself thinking all over again just recently: a Pietà.

For, a few years back (one day in January 2006), a 77-year-old “art activist pensioner” named Pierre Pinoncelli from Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (site, as it happens, of Van Gogh’s famous asylum) attacked Duchamp’s signature icon Fountain with a hammer, slightly chipping it, as it lay in state as the centerpiece to the Pompidou Center’s massive Dada retrospective in Paris. Many shocked newspaper readers the next morning (I am sure, at any rate, that I was not alone) were put in mind of that infamous moment, back in May 1972, when a 33-year-old Hungarian-born Australian geologist named Laszlo Toth, ecstatically keening “I am Jesus Christ!,” took a hammer to Michelangelo’s sublime Pietà in the Vatican, causing considerably more damage.

(With that act might Toth have been referencing the Beatles’ bang-bang line from “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” of three years earlier?) At any rate, while Toth was being almost universally decried as a cultural terrorist, a small band of radicals took to hailing his “gentle hammer” under the distinctly more Dadaist slogan “No more masterpieces!” Toth was eventually committed to an Italian asylum and then expelled from the country, and even though the sculpture was presently repaired, the attack left quite an impression. (A few months later, the National Lampoon ran a photo of the incident itself, Toth’s hammer-wielding arm raised in ecstasy, under the memorable caption “Oh my God, Pietà? I thought it said Piñata!” And some years after that, perhaps similarly liberated—or, alternatively, deranged—by the incident and its Duchampian precursor, Andres Serrano perpetrated his own Piss Christ.)

As it turned out, though, this most recent was not Pinoncelli’s first attack on Duchamp’s masterpiece. Back in 1993, in what to my own mind may count as the single most inspired feat of performance art of all time, Pinoncelli urinated into the sculpture as it lay on display, just down the road, in Nîmes, France.

At the time, he defended his action, explaining how he’d simply been trying to “give dignity back to the object, a victim of distortion of its use, even its personality.” This time around, he amplified that exegesis by explaining to reporters how, “having been transformed back into a simple object for pissing into after having been the most famous object in the history of art, its existence was broken, it was going to have a miserable existence… Better to put an end to it with a few blows of the hammer,” he went on modestly, esteeming his own gesture “not at all the act of a vandal, more a charitable act.”

Ah, the Resurrection and the Life of Art!

But I digress. The point I was trying to make (or to reach, anyway) is that Warhol is hardly the only one to have appropriated Duchamp’s gambit: another contemporary artist, Sherrie Levine, appropriated Duchamp’s urinal, tout court (in 1996, as it happens, just three years after Pinoncelli’s Nîmes attack), though she did go to the splendidly inspired trouble of having the thing gilded.

A gesture our friend Maurizio Cattelan (of Pope-Struck-by-Meteor fame, three issues back), seemed to amplify upon, a few years ago, in 2016, in partial homage to Trump’s impending ascendancy, when he installed a fully-working 18-carat gold toilet at the Guggenheim.

Meanwhile, another contemporary artist, Liza Lou, the MacArthur-Award-winning master whose métier for a long while there seemed to consist in meticulously beading the entire world, from kitchens to prison cells, eventually came to her own Duchampian moment, beading up all the surfaces of a lidless prison toilet, right down to the stain line in the abject-looking object’s bowl. In this instance though, appropriation verged on self- portraiture, for naturally she called the thing Lou.

*

CRYPTOMNESIA

Okay, so we are rounding the bend and heading for home, the end of our little notional journey is in sight but not before briefly pondering one of the most mysterious and peculiar of all convergent effects, and another one with a truly marvelous name, which is to say, “Cryptomnesia,” a bizarre subcategory under Appropriation in which the artist or writer or musician appropriates whole vast swaths of another creator’s work without being aware that he or she is doing so, fiercely denying having done so all the while.

Any of you want to call your band “Cryptomnesia”? If so, you might want to feature George Harrison’s 1970 hit “My Sweet Lord,” which as many of you know was subject to a half-decade’s copyright infringement litigation asserting that the former Beatle had lifted the opening of the tune wholesale from off of Ronnie Mack’s 1962 chart-topper “He’s So Fine,” popularized at the time by the Chiffons. Harrison forcefully denied the charge, though the judge in the case eventually found that he had indeed “subconsciously” done so, and he was hence ordered to pay damages (the beginning of a whole other crazy story, but just Google it). These sorts of challenges happen all the time in the music world, often on a considerably flimsier gold-digging basis.

But the cryptomnesia phenomenon is nevertheless very real, and one of the spookier such instances, a quarter of a century ago, involved two major writers, both of whom were being short-listed for the Nobel Prize at the time.

In a May 1993 issue of the New Yorker, in an article entitled “To See and Not See,” neurologist Oliver Sacks reported on the case of a fifty-year-old masseur whom he denominated “Virgil” who, after a life of sightlessness and at the behest of a near-messianically intent new wife and doctor, underwent an operation that completely restored his sight. And yet all did not go well thereafter. Because sight is not just an optical phenomenon but instead involves complex learned neurological processes, some of which may not in fact be learnable after puberty (as is the case as well, for example, with so-called wild children who first get exposed to language after puberty and hence never really master human syntax). Virgil’s previously-relatively-well-ordered life was turned upside down. In one passage, for example, he spoke of his horror at the fact that his own hand held before his face seemed positively monstrous in size compared to full-sized people on the far side of the room, an effect he could not get used to. And eventually he pleaded to be allowed to revert to blindness once more.

A bit over a year later, in August 1994, the great Irish playwright Brian Friel’s latest effort opened at the Gate Theatre in Dublin: Molly Sweeney, a two-act braid of three monologues detailing the story of a forty-odd-year-old woman, blind since birth, whose husband and ophthalmologist urge her into an operation to restore her sight, with results uncannily like those depicted in Dr. Sacks’s piece, for many paragraphs almost literally so, word for word.

The bizarre coincidence came to light when the New Yorker was on the verge of publishing a celebratory report on the new play by its London-based critic John Lahr, and it was noted in-house that long sample passages quoted by Lahr ran virtually verbatim identically to passages the magazine itself had published in Dr. Sacks’s piece the year before. (Sacks for his part had been mailed a copy of the new play’s script by his friend, an unknowing Peter Brook, who thought he might find the treatment of this strange neurological situation of interest, which needless to say Sacks did, though not quite in the way Brook had expected.) Urgent back-channel inquiries were launched, but Friel at first emphatically denied having read the New Yorker piece or for that matter any wider familiarity with Sacks’s story. When confronted with a memo laying out the particular overlaps, Friel subsequently acknowledged that he must have encountered the Sacks story somewhere in his research and he included a note acknowledging the debt in subsequent editions and programs of the play. But he was still bewildered by the experience.

It turned out that over a year earlier, the New Yorker’s editor Tina Brown had had a visiting Brian Friel over as a guest at one of her legendary dinner soirés, and that when conversation turned to the theme of blindness and the restoration of sight which Friel had recently taken to exploring in preparation for a project he was then gestating, Ms. Brown mentioned that she had just gotten in a fascinating manuscript on that very subject, subsequently (unbeknownst to Sacks) sending Friel over a copy of the doctor’s typescript. The fact is Friel never did see the piece in its New Yorker format, so the assertion that he must have, had understandably failed to jog his memory. Beyond that, Friel was indeed hoovering up all sorts of material at the time, distilling it in the context of his own longtime concerns (as evidenced for example in his earlier play, Faith Healer), and emerging with something altogether true to his own passions. The fact is that Dr. Sacks’s imagery was overpoweringly memorable—especially to someone as sensitive to language and metaphor as Friel—and it is entirely possible that Friel, in absorbing the imagery into his own gestating sensorium, completely forgot its original context, taking it on as completely his own.

At any rate, the point is that this sort of thing happens much more often than is generally assumed, so much so, as I say, that they even have a name for it. Years later, Sacks himself devoted the better part of an entire piece, called “Speak Memory,” in the New York Review of Books of February 21, 2013 on the wider implications of the phenomenon.

*

So, here on almost the diametrical opposite end of the spectrum from Apophenia (where human beings insist on discerning patterns where there are no patterns whatsoever), we have been considering instances where the reason two things might seem alike is because they are in fact alike. In artistic appropriation, far from hiding the resemblance, the artist is precisely making an issue of it, deploying the similarities across a field of playful philosophical-aesthetic perplexity. Cryptomnesiacs, for their part, may likewise be appropriating other people’s material, but for complex neurological and psychological reasons seem unaware that they have been doing so. But now we come to the very nether tip of the spectrum, in which the reason two things might seem the same is that someone is trying to pull something over on us. We have entered the terrain of

PLAGIARISM

Picasso is famously said to have proclaimed, “Good artists borrow; great artists steal.” But plagiarism clearly is not the sort of thing he had in mind. (Rather he was referring to the way strong artists happily incorporate the influences and examples of other artists’ breakthroughs into their own practice, and are only too happy to admit doing so.) (Up to a point, anyway, as we noted last time out in our earlier consideration of the Anxiety of Influence.) The plagiarist, on the other hand, incorporates large swaths of other people’s material, sometimes the entirety of a given project, and presents it as his own, making every effort to conceal the fact that he has done so. This sort of behavior is rightly frowned upon, and even its recent brace of pseudo-enthusiasts, such as Jonathan Lethem (who once delivered an entire lecture on the subject, almost every single sentence of which had been plagiarized from some other source—see the lecture’s inclusion as the title piece in Lethem’s collection The Ecstasy of Influence) are only too proud to highlight their wicked achievement, citing chapter and verse, something that sets them distinctly apart from actual plagiarists.

But even here we have subtle gradings, identifiable subcategories.

Forgery

Forgery, the act of fashioning or reproducing a likeness for fraudulent purposes, generally refers, in our context, to unique instances, as in works of art. You forge a painting or a sculpture, you don’t forge a book (you plagiarize a book), though you might forge a manuscript, and you can definitely forge a signature.

Artistic forgeries tend to come in two categories. Literal transcriptions, as exacting as possible, of specific original works by particular known artists with the intent of passing them off as the original; the sort of thing some people think might have happened after the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre in August 1911 (for a while even Picasso was suspected of having taken part in the caper), only to be recovered and returned two years later—or was it? To this day some people continue to surmise that the object returned was a brilliantly forged copy, and the original languishes somewhere else, perhaps in some secret billionaire’s boudoir—or that of his great-grandchild. (Admittedly, most people who continue to believe that are dismissed nowadays as borderline paranoid apopheniacs.)

Doubtless more common, or at any rate more lucrative, is the case of the forger who generates a painting, say, in the style of a given artist, or more precisely in the style of a particular period’s production by a given artist, and then markets it as if it were in fact by that artist. This is a multi-billion-dollar business, and fresh old masters and, for that matter, fresh new masters are constantly entering the market. The forger is the dark obverse of the connoisseur: he puts the connoisseur’s exacting knowledge to work in an attempt to fool his double, sometimes playing off that double’s self-regarding vanity, in an endless game of cat and mouse, in which sometimes the cat even is the mouse, and visa versa.

Consider in this regard the famous case of Han van Meegerem, the embittered Dutch academic painter and dandy, who in the period between the wars began generating a whole spate of distinctly clumsy Vermeers, improbably so except that all the top experts started staking their careers on the authenticity of the glorious new discoveries. Today we look on drop-jawed: how could the experts have been so deluded? But the fact is that Van Meegerem, no mean scholar himself, had perfectly pitched his production to a phase in Vermeer’s early career, an unaccounted gap between the Delft master’s early efforts and his mature production, for examples of which the experts were specifically searching. (Years ago, I sat at a friend’s kitchen table as she regaled her mother, who was busy cooking, with descriptions of a new boyfriend, who was the handsomest, the smartest, the gentlest, the coolest—after a long bit of which, her mother, stirring the soup, knowingly opined, “That’s hormones talking.” Such was at least in part the case with the expert reception of Van Meegerem’s offerings.) But it may be even more accurate to say that while Van Meegerems don’t look anything like Vermeers to us today, they may look exactly like what Vermeer looked like in the 1930s, or rather, like what people went to Vermeer to look for in those days. In that sense, it may be the case, mysteriously, that forgeries age faster than originals—yet another one of their disadvantages.

Van Meegerem’s case had a spectacular denouement. Happy to sell his Vermeers to anyone (and if truth be told a bit of a political reprobate as well), Van Meegerem was only too pleased to consort with the Nazis during Holland’s occupation, and his Vermeers presently made their way into the lavish collections of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, a circumstance which after the war subjected Van Meegerem to charges of criminal collaboration and even treason (after all he’d facilitated the transfer of some of the country’s greatest cultural treasures into the very lap of the enemy), charges from which he was only able to disentangle himself by painting a fresh brace of Van Meegeremeers while in prison awaiting trial.

Look, he exulted, far from being a collaborator, he should be hailed as a hero of the Resistance: after all, he’d pulled one over on the Nazis! The judges weren’t quite buying that last, however, and though Van Meegerem evaded the death penalty usually meted out to those convicted of treason, he was still sentenced to a year in prison on charges of falsification and fraud—a year the scoundrel never quite served out, dying of a heart attack before he could be released.

Counterfeiture

Forgers, as has been noted, tend to specialize in unique instances. Counterfeiters tend to prefer working in bulk. Mass producing counterfeit Gucci purses, for example, for sale at seemingly slashed-way-down (in actuality pumped-way-up) prices on rickety tables slapped together on busy corners in cities all over the world.

On the other hand—and here we come, finally, to the very last drawer— the true masters of the craft, tiring of making counterfeits just so that they can make money, wonder why not just make money itself?

Not that artists haven’t found a way to upend even this seemingly purely nefarious activity. In fact I once wrote an entire book about such a one, the fiendishly clever and endlessly confounding J.S.G. Boggs, who liked to draw money and spend his drawings, and especially liked to get arrested for doing so, charged with counterfeiture or reproduction of currency, so that then, time after time, he could thwart his prosecutors by common-sensically convincing juries that he’d be crazy to try and pass drawings which were manifestly more valuable than their supposed face value, that if anything his were the “originals” and theirs were the reproductions, and so forth. But before I digress any further, may I suggest anybody interested just go out and find the book.

*

ONE LAST DIGRESSION BEFORE LEAVETAKING

As it happens an odd conflation of the last two macro-categories occurred in 1903 when, shortly after the publication of her autobiography, Helen Keller got accused of plagiarism.

Let me repeat that: Helen Keller was accused of plagiarism, and was apparently quite devastated by the accusation. (Although the fact of any such plagiarism, on reconsideration, is not as unlikely as one might suspect, since a great part of the famously deaf-and-blind Keller’s experience of the world would necessarily have been read to her, either through Braille or through hand-signals, such that things she remembered as her own experience might well have originated as verbal narratives rather than things directly seen or heard, of which, in her specific case, there had been precisely none. Thus for example her “memory” of a visit, say, to the Matterhorn, might end up dove-tailing quite closely with the account of same in a Braille edition of Beidecker’s.)

At any rate, in the midst of the scandal, the incomparable Mark Twain weighed in with a consoling letter to Ms. Keller, one which (notwithstanding any of our earlier comments on the subject) might also serve as an ongoing caution to the rest of us. “Oh, dear me,” began Keller’s dear sage friend, “how unspeakably funny and owlishly idiotic and grotesque was that ‘plagiarism’ farce!

As if there was much of anything in any human utterance, oral or written, except plagiarism! The kernel, the soul—let us go farther and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances—is plagiarism. For substantially all ideas are second hand, consciously or unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources and daily used by the garnerer with a pride and satisfaction born of the superstition that he originated them; whereas there is not a rag of originality about them anywhere except in the little discoloration they get from his mental and moral caliber and his temperament, which is revealed in characteristics of phrasing.

The superstition that he originated them! And I especially love that last proviso: “the little discoloration they get from his mental and moral caliber and his temperament, which is revealed in characteristics of phrasing.” One really couldn’t ask for more.

*

SO, NOW WHERE ARE WE?

Where does all of that put us with regard to the question with which we started, the validity of Mr. Morris’s assertion of an Uccello/Fischl convergence in that specific instance, and more precisely the specific character such a convergence might be taking?

Well, we may be dealing with apophenia, or even leapfrogging apophenia in this case as I too have begun to buy into Morris’s assertion. If it’s not apophenia, it may simply be coincidence, but I suspect it’s more. It may be conscious allusion on Fischl’s part, or else an instance of unconscious influence (bad uncouth men simply reeking of a certain rank, fire-snorting dragonhood all across our culture, and maybe all cultures).

The nice thing in this instance is that Master Fischl is still around, and we could simply ask him—were he willing to tell us…. Master Fischl, are you out there?

In fact he is out there, and recently I did get a chance to ask him, and he denied any conscious awareness of the Uccello painting in advance of the rendering of his own, or for that matter anytime before our conversation.

On the other hand, the nice thing about convergences is that it really doesn’t matter whether the artist intended the echo in question, consciously or unconsciously. The artist being—pace Diderot—merely the first witness of the completed painting and in the end capable of claiming no greater status than that. After him there will be further witnesses—all the rest of us, all of us equally privileged viewers by virtue of the fact that we all draw equally upon, and are all equally bathed in, the confluence of crosscurrents that is the wider cultural surround, convergence in that sense being nothing less than another name for culture itself.

Or, as a friend of mine commented to me the other day—quoting who? she couldn’t quite remember, she thought maybe it might be Ezra Pound but couldn’t quite be sure—“Culture begins when we forget our sources.”

THE END

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Those sticklers among you who have been following closely will remember how last time we indicated that we would be making an Important Announcement with this issue. Ah well. Never mind. But we will be doing so next time, and there will be a whole cornucopia of other cool stuff, just you wait and see….

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Unfortunately, the post of Timothy Snyder is a total garbage in term of literally everything. Ok, I totally understand that Russian and Ukraine languages are hard to study and especially to know that much so to see and understand the difference in spelling and so on. As well as for me it’s super hard to learn Chinese and Japanese. So guess what? I would never try to analyze anything to public and post it if I have no idea what I’m talking about. Almost every single line of that post is a bs and a garbage from a knowledge and quality point of view. I wouldn’t even comment regarding the “meaning” as it makes no sense to discuss that among the educated people. It made me understand that everything should start from very begging. If a society needs to argue on some matters it should invest quite a lot into educating themselves so that to stay on the same page. Maybe that would increase a level of mutual understanding at the end. Peace and luck to everyone in the world!

Hello Wren and everyone. This blog is right on and truly enlightening. I am not a pacifist, and Ukraine reminds me of my own heritage of 1956 in Hungary.

It is appalling to me that the conversation and actions in our world are consistently turning right, inevitably leading to fascism. I applaud the lesson on language, the popularizing of this neologistic writing, and pray that the bloodletting will stop real soon. The hard work of reeducation worldwide and re-orientation of all languages is imperative. We need to focus the whole world on changing the climate and constructing a world for our children..... which in my humble opinion is de-centralized.... and based on truth, not dogmas......

Thanks for the insight:

Steven Ormenyi