WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Thinking about lucidity as regards responsibility when it comes to “collateral damage,” and the flight from such lucidity, as refracted by way of a famous scene from The Battle of Algiers; followed by Larry McMurtry’s thoughts on having been a Minor Regional Novelist.

* * *

Main Event

FURTHER REFLECTIONS ON CURRENT EVENTS

I was having a dream, you know, one of those dreams where things just keep going from bad to worse and then worse still, everything narrowing to a point where there’s seemingly no way out, except that suddenly I woke up, momentarily disoriented except that pfew, I came to realize that, double-pfew, it had all just been a dream. There are, however, of course places in the world where it’s my own sense of outspreading relief that is the dream and actual things on the ground do in fact just keep going from bad to worse and worse still: a terrible, terrible reality that I myself in my dreamy cozy sense of blithe security just keep on subsidizing and underwriting.

Anyway, for the past several weeks, a scene from the remarkable 1965 cinema verité agitprop film The Battle of Algiers has kept thrumming through my waking mind, or rather, as I realized the other evening, what I’ve been teasingly almost recalling was the rhetorical use to which I myself once put that scene in a New Yorker Notes and Comment piece I composed back in August 1986, at a moment when President Reagan and his allies were trying to get Congress to fund another tranch of the Contra War that they—we—were waging against the fledgling Sandanista regime in Nicaragua. To wit:

The New Yorker, Comment, August 25, 1986

(also included in Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences)

Observing the recent Congressional debates over the funding of the Nicaraguan Contras in their campaign to bring down the Sandinistas in Managua, I’ve been haunted by memories of a scene in Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1965 film The Battle of Algiers. The film was a stirring piece of agit-prop, a gritty, cinéma-vérité-style re-creation of the urban terrorist campaign that preceded Algeria’s liberation from French colonial domination in the early ’60s. Pontecorvo made no attempt to mask his allegiances in the film—his sympathies were unmistakably engaged on the side of the guerrillas—and yet he evinced a remarkably steady kind of lucidity. Particularly in the scene that keeps haunting me.

By that point in the story, the Algiers Casbah had been more or less cordoned off by French military police, and residents were having to pass through elaborate security checks to enter and leave. The guerrillas therefore began using women, who would presumably arouse less suspicion, to deliver their bombs to the civilian colonial targets on the far side of the cordon. In the sequence I’m remembering, the camera followed one such woman as she picked up her bomb, stowed inside a basket, and carried it through the narrow streets of the Casbah, across the checkpoint (undetected), down into the broad, leafy avenues of the cosmopolitan part of town, and into a café packed with breezy, insouciant French colonials. She set her basket down by her feet, under a bar stool, nudged it further under the bar counter, and then, in accordance with her instructions, dallied for a few moments, so as not to provoke notice.

And here’s where Pontecorvo’s lucidity entered, because during the next minute the camera adopted her point of view. It would have been easy to populate those seconds with her perceptions of flirting, cocky soldiers or rich, spoiled colonial teenagers out on a lark. Instead, Pontecorvo has his woman’s gaze come to rest on a manifestly innocent toddler, lapping at an ice cream cone.

She continues watching that child and some other people, for a few seconds more, then gets up and ambles away, out into the street and down the avenue; some moments pass (the camera returns to the café for one last look at the child, his cone now finished), and then there is a tremendous explosion.

That scene was in turn echoed, a few years later, in 1976, roughly halfway between Pontecorvo’s film and the current Congressional debates, in a remarkable poem by the Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska, entitled “The Terrorist, He’s Watching.” Szymborska likewise adopts the terrorist’s point of view, in this case after he’s dropped his package off in the bar and as he stands across the street, waiting for the bomb to go off at 13:20. “The distance,” Szymborska notes, “keeps him out of danger, and what a view—just like the movies.” In Baranczak and Cavanaugh’s sinewy translation, the terrorist observes how: “A woman in a yellow jacket, she’s going in. / A man in dark glasses, he’s coming out. / Teenagers in jeans, they’re talking. / Thirteen-seventeen and four seconds. / The short one, he’s lucky, he’s getting on a scooter, but the tall one, he’s going in.” At one point a girl with a green ribbon approaches the bar, but just then a bus pulls in front of her. “Thirteen eighteen. / The girl’s gone. / Was she that dumb, did she go in or not, / we’ll see when they carry them out.” At thirteen-nineteen, a fat bald guy leaves the bar, but “Wait a second, looks like he’s looking for something in his pockets and / at thirteen-twenty minus ten seconds / he goes back in for his crummy gloves.

Thirteen-twenty exactly.

This waiting, it’s taking forever. Any second now.

No, not yet.

Yes, now.

The bomb, it explodes.Pontecorvo, for his part, back in his 1965 film, seemed to be saying, “Yes, such tactics are perhaps sometimes necessary, but, my God, the cost! The terrible cost, and the awesome responsibility!” He didn’t allow his agitprop characters any easy evasions.

And it’s that refusal to evade responsibility which has haunted me these past few weeks as the Senate considered once again, and probably not for the last time, the question of military aid for the Nicaraguan Contras. The proponents and the opponents of extending a hundred million dollars in such aid seem to be inhabiting different universes, so divergent are their interpretations of what is going on down there in Nicaragua and what this vote implies. That in itself is eerie, and gives one pause. But what has really been bothering me is the sense of distance, of sublime remove, on the part of the proponents of the assistance. It would be one thing if they were saying, “My God, what a sorry pass things have come to that today we have to vote to expand a war that will inevitably result in hundreds of deaths and the mutilation of hundreds of innocent bystanders—men, women, children. It’s terrible, and yet we have to do it, for such-and-such a higher cause. We do it with heavy hearts and with our eyes wide open. Still, do it we must.”

However, they have been saying nothing of the kind. Through copious recourse to euphemisms of the “pressure for negotiation” and “nurturing the movement toward democracy” variety, they have managed to empty their positions of all its actual consequences. Their vote will have terrible consequences in the real world. The legislators have simply contrived, if only for the time being (and hardly for the first or, one fears, last time), to evade all responsibility for them.

At first glance, it might seem that that piece lines up most closely with the moral quandary of the Hamas insurgents, their situation after all being the most obvious correlative to that of the the Algerian insurgents. And to be sure one does need to wonder what the Hamas leaders had going on in their heads that October 7th morning when they launched the onslaught that would go on to feature such horrific pillage, slaughter, and sexual violence—and those leaders and their lieutenants of course need to be held to strict account for all the war crimes that proliferated from out of the execution of their orders (whatever those initial orders might have been).

But the same calculus, at very least, needs to be applied to the Israelis in their wildly disproportionate and ever more harrowing response across the weeks and now months since. And here is where the analogy feels most telling. Setting aside for the moment what Netanyahu and his allies could possibly mean by their endlessly repeated contention about the war’s aim being “the utter elimination of Hamas,” let’s focus instead on the war’s devastating means, the way, for example, that dozens of civilians’ lives are regularly put at risk in aerial bombing sorties aimed at “eliminating” a single Hamas commander, with hardly any potential targets (hospitals, schools, refugee camps, or the like) deemed off-limits. (According to a remarkable recent piece at the 972mag.com website, the Israeli targeters even refer to tables containing incredibly detailed advance tabulations, building by building, of the likely collateral damage to be expected in each raid, not that such calculations appear to give them much pause). As one commentator recently pointed out, it’s no longer the case that large numbers of civilians are proving collateral damage in raids on individual Hamas targets but rather that Hamas targets are at best making up the occasional collateral damage in the indiscriminate carpet bombings of Palestinian civilians. Spokesmen for the Israeli Defense Forces blame Hamas for using civilians as human shields, a somewhat difficult assertion to parse given the sheer density of population in Gaza (perhaps the highest in the world), even before the Israelis began demanding that vast swaths of that population abandon their homes for ever more crowded if briefly safer zones further south. Which is not even to mention the wholesale denial of the bare minimum requirements of water, food, medicines, fuel and the like to which those squeezed populations are meanwhile being subjected. And we all know the resultant statistics, how coming on 20,000 Gazans are known to have been killed so far, with over 70 percent of those being women and children (and that is not even counting the corpses still under the rubble of utterly leveled apartment blocks, and with much higher mortality rates predicted for the coming weeks owing to the increasingly rampant rates of disease, starvation, and exposure.)

I say we all know this, but that’s the nub, isn’t it, because do we? For starters, do they, do the majority of Israelis know, let alone acknowledge, the sheer slaughter being perpetrated in their names? Report after report describes a general media landscape in Israel utterly focused on endlessly recycling the trauma of October 7 and the ensuing fate of the innocent hostages (Hamas’s hostages, that is, not the vastly larger numbers of Israel’s own) with little concern over let alone actual reportage on the situation of Gazan civilians and the daily terrors to which they are being subjected. Not that Israelis couldn’t avail themselves of that knowledge if they wanted to (just sample Al Jazeera.com’s live coverage from out of Gaza every once in a while, or drop in for such passages as this from a recent NPR Morning Edition), but they don’t. Easier to follow the lead of their leaders who dismiss Gazans, en masse, as “human animals” who all asked for hell and now are going to get it. Splendidly various are the strategems people have for evading the manifestly obvious, the stories they tell themselves and the distractions they pile on by way of self-obfuscation.

And us, too. We Americans. For let us at least be clear that, what with the turbocharged delivery of bombs and weapons and intelligence, and the diplomatic cover provided by our ever more lonesome vetoes at the Security Council, this is becoming every bit as much America’s war as it is Israel’s—or at any rate is being perceived as such throughout the world, especially in the region. Biden and Blinken and our other leaders comfort themselves by counseling the Israelis to take it easy and to scrupulously observe the laws of war and to open the way for serious humanitarian interventions, receiving bland Israeli assurances that are just as quickly superseded by yet further escalations and violations on the ground—and what more, they seem to stammer, can they be expected to do, Israel after all being its own sovereign nation?

Except for, of course, everything, starting with noting that we too are our own sovereign nation and could, if we so roused ourselves, exact consequences for Israel’s blatant disregard of our counsel and the world’s concerns. We could stop vetoing those Security Council resolutions and choose to absent ourselves (if only by way of abstention) from the company of the nine sole other countries in the General Assembly who chose to vote against the rest of the world’s demand for an immediate humanitarian cease-fire (and in that context let’s do give a shout-out to our distinguished cohort in that regard: Israel, Austria, Czechia, Guatemala, Liberia, Micronesia, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, and Paraguay: quite the company of confederates, that). We could make further military aid conditional on actual behavior on the ground; we could refuse to work in any capacity with Netanyahu and the other extremist members of his cabinet; we could declare that a large swath of upcoming financial aid destined for Israel will instead be given over to Gazan reconstruction and insist that all future aid beyond that will be contingent on steadfast movement toward an actual two-state solution (which will require dismantling of illegal settlements and for that matter population transfers out of many of the other “facts-on-the-ground” townships that are just as illegal from the viewpoint of international law).

We could do all sorts of things, or we could just go on blathering on about “nurturing the movement toward democracy” and hopefully exerting “pressure toward negotiation,” as the bombs, they keep exploding.

*

{For another important summary vantage, just out today, see Jeremy Scahill’s piece This Is Not a War Against Hamas (“The notion that the war would end if Hamas was overthrown or surrenders is as ahistorical as it is false”) at The Intercept.}

* * *

Commonplace Book

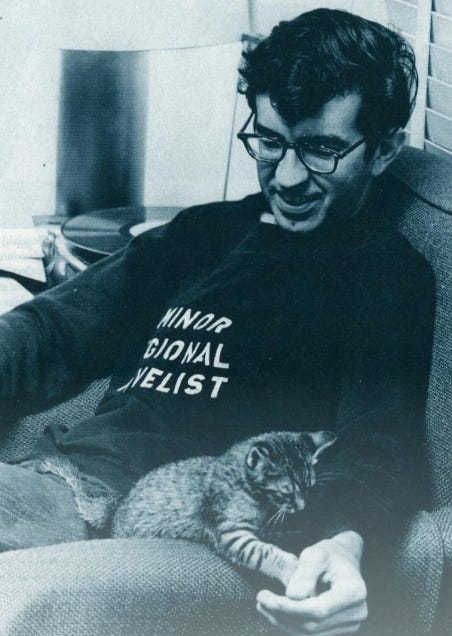

Veteran readers of this Cabinet, who may recall how much I loved Larry McMurtry (see Issue #9), will perhaps share in the delight I took in this passage from late in Tracy Daugherty’s wonderful recent biography of the Texas master (author among others of Lonesome Dove, The Last Picture Show and Terms of Endearment):

As usual the contrarian in him tried to squeeze in the final word. In one of his last interviews, he said he really was what his old T-shirt once proclaimed him to be: “I am a minor regional novelist. You should not let minor put you off a book.” Minor fed the great streams of literature, he said, providing tributaries to the thrusting, ongoing current. “Very few writers in any generation are not minor. To make it to minor puts you in the company of Trollope in the nineteenth century…and a jillion others…. In the last generation, I try to think of anyone I think is really major. In the generation of Mailer and Roth and Bellow [the usual suspects], I think all those guys are minor. The one person I think is not minor is Flannery O’Connor. I think she was a true painful genius… But there’s nothing wrong with being minor. If you’re in the show, still writing books…it’s fine if you’re minor. I’m glad I got that high. Not everybody does.”

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

* * *

* * *

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.