WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This week a pair of films from the incomparable Bill Morrison on racialized policing in America—the first, just released to a wider public, Incident, a real-time split-screen evocation of a 2018 police killing of a civilian in Chicago and its immediate aftermath; the second, Buried News, drawing on long-lost stateside newsreel footage from the years just after World War One.

* * *

The Main Event

INDEX SPLENDORUM

A Bill Morrison Double Bill

on racialized policing in America

Late on the afternoon of Saturday, July 14, 2018, with the city of Chicago already in the grip of a spate of stunning revelations regarding an earlier police killing, “3rd District Police Officers were on foot patrol in the vicinity of East 71st street”—this in the words of the police department’s first release on the subject later that evening—when “the officers approached a male subject exhibiting characteristics of an armed person and an armed confrontation ensued resulting in an officer discharging his weapon and fatally striking the offender. The offender was transported to a local hospital where he was later pronounced.” (Pronounced what? Some truly exquisite bureaucratese there.) “A weapon was recovered at the scene. No other injuries were reported.”

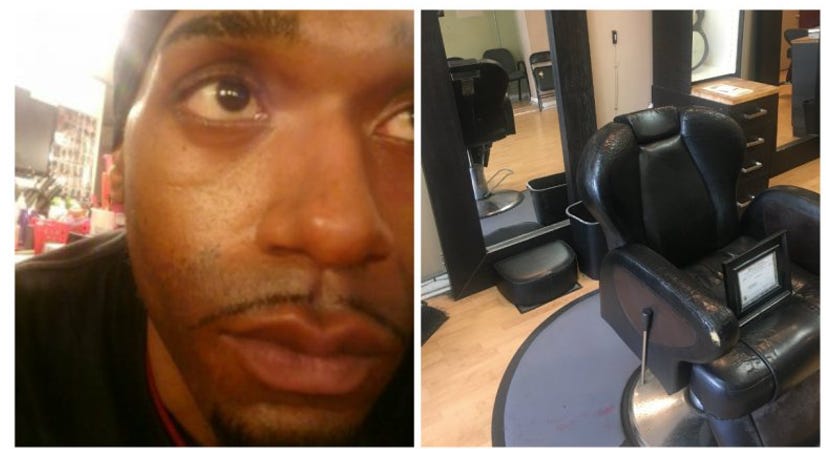

The pronounced alleged shooter was Harith Augustus, a 37-year-old barber from a shop just down the block, but the trouble was that this account in no way jibed with that of other nonpolice eye-witness passers-by. Tensions were rising precipitously, crowds gathering, local activists demanding the immediate release of body-camera and other video footage, and the mainstream media picking up the scent of yet another shooting scandal.

In response, the police quickly released an archly edited version of an extremely limited amount of the video material in their hands, the police commissioner declaring, “We’re not trying to hide anything, we’re not trying to fluff anything, the video speaks for itself,” with the Fraternal Order of Police union chiming in by way of an angry statement to the effect that “The bias and self-generated hysteria by the media demonstrates a profound indifference to the burden of a police officer being involved in such an incident even when, as in this case, the shooting is textbook legitimate {…}: Officers stopped an individual with a gun. The offender pulls it and gets killed.”

That official response initially appeared to do the trick, at least with regard to the mainstream media who, sufficiently cowed, pretty much abandoned the story (Never mind, folks, nothing to see here, let’s all just keep moving along). But a group of community activists continued to demand full access to all of the tapes and were joined in this effort by Jamie Kalven of the Invisible Institute, a non-profit journalism production company based on the South Side of Chicago, who had earlier taken the lead in similar litigation with regard to that other earlier police-shooting scandal consuming the city.

Eventually succeeding in getting the police to release a veritable (although still not quite complete) horde of video material (from body-worn and dashboard cameras, private local business security cams, and nearby police surveillance towers), the Invisible Institute secured the help of Forensic Architecture, the distinguished multidisciplinary research group led by Eyal Weizman and based at Goldsmiths, University of London, that uses architectural techniques and technologies to investigate cases of state violence and violations of human rights around the world. Together the two organizations embarked on a detailed review of the evidence, culminating in a remarkable exhibit at the following year’s Chicago Architecture Biennial entitled “Six Durations of a Split Second: The Killing of Harith Augustus,” which not only completely upended the police department’s account (for starters, the so-called offender at no point pulled his concealed gun out of its holster; on the contrary, he was in the process of complying with police requests to pull his permit to be carrying such a gun out of his wallet) but yet more forcefully went on to interrogate the whole basis of the standard police defense that in such instances its officers should be given the benefit of the doubt since they always have to make “split second decisions.” Kalven and Weizman simultaneously published a full account of their findings in the September 19, 2019 issue of The Intercept, which is well worth reading on its own merits and includes links to the meticulously realized and utterly engrossing second-by-second and subsequent hour-by-hour and day-by-day recreations of what had happened leading up to and growing out from that fateful evening. (See, for example, the first one here.) Kalven in turn followed that piece a few years later with another, on August 23rd, 2022, again over the Intercept, with an update after managing to dislodge the final crucial videos from the reluctant grip of the police bureaucracy.

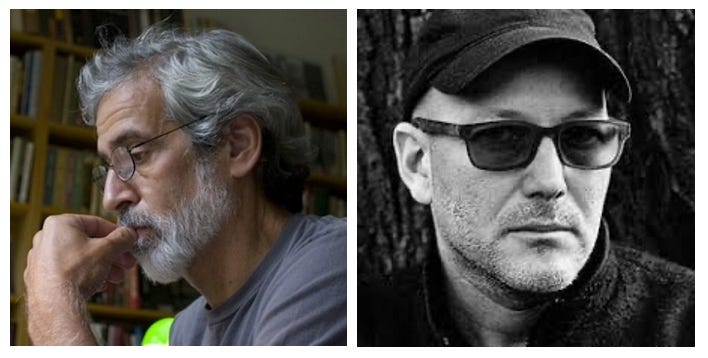

Which is where—and this is the point of the story from our point of view here at the Cabinet today—Bill Morrison first got wind of the story. As some of you may know, I have been following the celebrated avant-garde documentary filmmaker for some years now, beginning relatively early in his career with a 2002 piece in the New York Times magazine on his breakthrough feature Decasia and following up a decade-and-a-half after that with a 2016 Vanity Fair piece on his own follow-up chronicle Dawson City: Frozen Time. Both of those, as for that matter most of his other work till recently, grew out of his profoundly reverential dives into the world’s far-flung archives of long abandoned so-called “orphan” cellulose nitrate film stock from the earliest decades of the twentieth century, most of which is now rapidly delaminating and disintegrating. At a certain point, most archivists give up on the worst such cases, remanding them to their so-called Morrison-bins, for those are where Bill finds his true treasures, as the imagery encased in the filmed narrative does doomed battle with the ever-encroaching organic rot eating away at the filmstock. Working with some of the foremost composers of our time, Morrison time and again weaves mesmerizing, heartrending lyric dream collages out of such material (as, for example, here)—films that paradoxically feel (and indeed are) manifestly of this moment (after all, it took this long for the filmstocks to reach their current state of distress).

Anyway, Morrison, who has long been based on the Lower East Side of Manhattan but grew up on Chicago’s South Side, was instantly drawn to the material in the Intercept story and soon contacted Kalven, inquiring if he could be allowed to explore the entire archive of the project’s hard-won video haul. Kalven and his colleagues agreed, and Morrison threw himself into his own project of excavation, emerging several months later with an entirely fresh way of seeing—both in terms of the material at hand and of his own filmmaking style. The 30-minute film, entitled Incident, consists of a split-screen interweaving in real time of constantly shifting camera viewpoints, and its meticulously even-handed Rashomon-like method is compoundingly devastating. Released last year, the short film proved a growing success on the Festival circuit and has only just made its way to wider public release by way of the New Yorker’s video division.

I have some further things I want to say about the film, but you should really just watch the thing for yourselves first. Seriously, you really should! And I will catch you on the far side.

Link here.

To begin with, of course, it goes without saying that the tragedy underlying the whole incident is utterly excruciating (though of course it is likewise precisely the problem that for the longest time, that tragedy indeed literally went without even being acknowledged, at least at the official level).

But I’d like to turn, at least at the outset, to a consideration of the sheer artistry of Morrison’s film, how even though its pacing is entirely dictated by the inevitable facticity and specificity of the tick-tock of the film’s method (all Morrison has done is to expertly align the time-signatures of a wide array of simultaneously running cameras and then cut in and out amongst them, guiding the viewer’s attention across a shifting grid of all that simultaneity), it is still remarkable how many editorially flecked or at any rate consciously discerned and foregrounded themes nevertheless emerge.

The film observes the Aristotelian unities (of time, of place), its action framed as if by Sophocles himself—starting, in medias res, with the uncanny happenstance of how, zeroing in from outer space onto this one specific little block on Chicago’s South Side—the view (from the police surveillance tower) perfectly bisected by an intervening pole—a figure comes staggering into the scene and tumbling to the ground, and just then, at the very moment that death seems to engulf the body, a white gull goes gliding by (a wash of grace, as it were, as if carrying away that body’s soul). There follow several moments of confusing action still transpiring in complete silence (the tower, dashboard, and other stationery cameras feature no sound) and it’s only as the police body-worn cameras kick in, as one by one the converging officers activate their audio-enabled devices (albeit a bit late), that the first sound we thus hear, a few seconds after the fatal shot, is that of the police shooter himself reporting in: “Police shot, er, shot fired at police, police officer sh—fuck.” (Is that “er” rather perhaps a hesitating, recombobulating “or”—which is to say a policeman has been shot or rather a shot was fired at the police; and in fact, in the next phrase, is the voice, in effect reeling, starting to acknowledge that a police officer was in fact the only one who did the shooting, though it immediately cuts that thought short. Fuck, indeed.) The entire moral arc of the coming story anticipated in those very first few words.

Morrison then pulls back fifteen minutes to set the stage, introducing the characters one by one along with the wider general context, before bringing us back into the prior action, this time as seen from ground level. Remarkable, however, the way that across the next two minutes of real time, what starts as a desperate, lunging, confused grasping after explanatory context on the part of the reeling officer (“Why did he have to pull a gun out on us?”) gets amplified and reified by his hyperventilating partner (“He was going to shoot us!” and later “You did nothing wrong, Dude, he had a fucking gun, I thought I was gonna die.”)—all of this despite the fact that we have just seen another officer come over to the prone body on the street (now properly zip-tie handcuffed by still another officer) and lean down so as to unstrap and pull the dead man’s manifestly unused gun out of its holster. The self-defense narrative has nevertheless somehow already become the master narrative, almost all the other converging officers (and later the downtown brass) eager to embrace it, and actively pushing away any alternative theories. Literally so, in the case of the surrounding neighborhood witnesses, none of whose names get taken down for further interviewing, all of whom are being pushed away, as the crime scene is getting cordoned off. Everyone showing far more concern for the shooting officer (“You did nothing wrong, you’re going to be okay”—as he gets spirited away for his own protection) than for the body lying there in the street (at one point we hear how a passing woman who identifies herself as a nurse volunteers to check on the prone figure but is likewise pushed away, beyond the cordon sanitaire). The police don’t even evince any interest in talking to the neighbors who identify the corpse (“He’s the barber! He cuts hair and he don’t do shit, he don’t gangbang!”)—one fellow says he was just on his way to his own haircutting appointment with the guy. No interest whatsoever: no investigation, indeed the very opposite. At one point the very officer who zip-tied the prone unconscious figure, apparently as per official procedure, is captured (almost too perfectly) by his own body-cam, lathering his hands with sanitizer and scrubbing and scrubbing away. (And not metaphorically, for actual real—what is he afraid of? that he might have contracted cooties?) Other officers keep cautioning each other to be careful what they say, their cameras are still on, and one by one we see them turn them off (and the plethora of viewpoints begin to narrow down accordingly).

All the while the surrounding crowd have been serving as a sort of Greek chorus, offering up a countervailing narrative—one that time and again feels more germane to what is actually going on. “You took the officer away so you could get your stories straight!” they shout accusingly, which is about right. Toward the end of the real-time sequence, speaking of countervailing narratives, a lone black officer, late arrived on the scene, is seen taking down notes, and in passing—you have to keep your eyes and ears peeled if you’re going to catch it—he identifies the situation as a 1-1-0 (a first-degree murder) and at one point disconcertingly characterizes the prone body as “the victim.”)

At length the officers impose on the ambulance crew to take the dead body away (they are initially reluctant to do so, this is not their job, not proper procedure, but at length, noting the rising agitation of the crowd, they agree to), and, thus loaded, the ambulance pulls off, while at the same moment, all the officers who haven’t yet done so get ordered to turn off their cameras already for godsake—and the screen reverts to the mute vantage of the police pole surveillance camera, as the text scrolls how that evening police charged the remaining crowd with raised batons and arrested four protesters (a further incident, a virtual police riot, exhaustively anatomized in the “Six Durations” show’s third video), how eventually two of the original officers would receive strikingly minimal reprimands and temporary suspensions, how four days after the events portrayed a memorial service was held for Harith “Snoop” Augustus at the Sideline Studio barbershop where “he was remembered as a quiet, patient and peaceful man,” and how “He is survived by a daughter, who was five years old at the time of his death.” At which point the screen goes dark.

But we are not quite through. Morrison now reverts one last time, by way of slow-motion flashback, to the sequence leading up to and through “Snoop” Augustus’s shooting, silent at first, everything proceeding with inexorable inevitability, and then the audio lurching back on—“Police shot, er, shot fired at police, police officer sh—fuck”—followed two beats later by a dispatcher’s voice (which we may not have noticed the first time through) squawking, “What we got and who are you?” Text that now hangs in the air, as the screen goes dark once again.

“What we got and who are you?” serving, as Morrison surely realizes, like a Sophoclean envoy (close parens, as it were, to that gliding gull at the film’s beginning) aimed right back at his audience, at us. What do we have here and who are we? As such, hanging in the air like that, they recall Gauguin’s “D’ou venons nous? Qui sommes nous? Ou allons nous?” (“Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?”—the title, it occurs to me, that the painter gave to his own racially charged Tahitian canvas). And for that matter, as well, speaking of museum pieces, the equally famously charged last lines of Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo”:

{…} for there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

As indeed there isn’t any such place (all those cameras!). As indeed we must.

*

A few last thoughts before moving on.

That final slow-motion repetition of those fatal last seconds of Mr. Augustus’s life there at the end brings out other and yet further laudable and yet countervailing aspects of Morrison’s film: its scrupulous attentiveness to specificity and persistent tolerance for ambiguity. Because for all the police department’s frantic subsequent obfuscations, this was clearly not in the first instance a case of easy self-evident racist villainy, in the mode of Derek Chauvin’s nine-minute asphyxiation of George Floyd, or the legions of straightforward lynchings that preceded it. Nor are we dealing with a uniformly resented police occupation of a subjected community. Remember, the officers were there at the specific behest of the local merchants and other neighborhood members who felt themselves under siege by gun-toting drug dealers, gang members, and common criminals. Indeed, if anything, one of the main causes of what happened that day was the sheer pervasiveness of guns on the local streets—which is probably why Augustus himself was carrying a gun, albeit entirely legally, for that very reason, out of concern for his own self-defense—such that a young, inexperienced probationary officer might also have had every reason to feel himself under threat: he might honestly have misread Augustus’s staggering turning (if only that police car hadn’t been passing by, momentarily blocking his straightforward flight!) as a reaching for the weapon everybody knew was there, and indeed responded with his own split-second reflex. (On the still other hand, as the Forensic Architecture team pointed out in that first of their Duration videos {at minute 8:10}, none of the other officers there on the sidewalk had reacted in that way.)

In any case, as Kalven has pointed out, the probationary officer himself had only just recently been marinating in a subtly racist training regime which had time and again paraded accounts of officers who, momentarily dropping their guard and giving the civilians they were interacting with the benefit of the doubt, had found themselves coming under sudden and sometimes fatal gunfire. As Kalven further noted, such trainees were hardly ever subjected to obverse case studies of the sort presented in Morrison’s film. So that, indeed, it is to be devoutly hoped that one day Incident itself may achieve its own canonical place in the curricula of police academies.

That could be one place we ought be going, a concrete way we might begin to change our communal lives.

*

Speaking of which, for those of you in the New York area who might like to have the opportunity to experience Incident on a big screen, as it obviously was meant to be seen, there will be such a showing on Thursday September 19th at 7 pm, at the Great Hall of Morrison’s alma mater, The Cooper Union, followed by a conversation among Morrison, Jamie Kalven, and Walter Katz of the Innocence Project. (Note: This will be a free event, though prior registration will be required here.)

As Morrison was telling me about this upcoming screening the other day, he mentioned how at a similar event in Chicago last year, under the auspices of my own old colleagues at the Chicago Humanities Festival, members of Augustus’s up-till-then extremely private and reticent family had shown up, and how at the end of the screening Augustus’s mother had risen to say how gladdened she was that “Now the world can see what happened to my son, and I want you to spread that word as far as you can” (Bill and I were both reminded of a famous statement to similar effect in the very same city almost seventy years ago, by the mother of Emmett Till.) Bill also told me how, at the end of the event, his own mother had gone over to pay her fervent respects to her fellow South Side resident, a poignant moment captured by Bill’s sister Sarah, whose photo he subsequently sent me:

*

Finally, as I say, I myself have been thinking about how this radical new turn in Morrison’s own filmmaking approach relates to his earlier filmography. As he and I took to talking about this in that same phone conversation the other day. I told him how I’d been struck by one fan of his whose gloss I’d read online, that of a certain Shawn Glinis:

Morrison's devotion to archival film via remixing as a form of spiritual preservation/renewal of something once thought lost finds a new and very surprising vein in Incident, where his archival materials are not lost but contemporary and completely open to the public. What is lost, of course, is Augustus' life, as well as any responsibility or accountability the law has toward the life it carelessly takes.

For my own part, I suggested how whereas with Decasia and Dawson City and their ilk, the once substantive solidity of the prior world seems to be actively dematerializing right there before our eyes, with Incident, by contrast, it is as if the roiling chaos and smeary ambiguity of actually lived reality keeps getting, again right there before our very eyes, gripped and polished into a frozen dominant (albeit counterfeit) master narrative,.

Morrison harrumphed a bit at my neat little conceit—a speculative stab too far, I suppose—but he then went on to note how just a few years before Incident, in the immediate wake of the events of January 6 at the Capitol, he’d actually already plumbed parallel material in that prior register, dredging previously-unused long-lost footage from the Dawson City Archive to explore similar instances, albeit long and deeply repressed, of racialized policing and social control in the prior of history America (in the immediate years after World War One, to be specific), for a short he’d taken to calling Buried News.

Indeed, he said, he wished there were somewhere he could show the two films side by side. To which I crowed, “But that is what the Index Splendorum is for!”

And so, without further ado, Part Two of today’s Double Bill:

Bill Morrison’s “Buried News”

Link here.

* * *

POSTSCRIPT TO THE FOREGOING

Just as we were getting set to go to press, Bill Morrison wrote to alert me to another viewer comment about the relationship between Incident and its prior antecedents in his filmography, one which posted only just the other day on Letterboxd public discussion forum, from a correspondent who identified himself simply as “dunson,” to wit:

Watched by dunson 03 Sep 2024

Morrison bridges the gap between the archaic worlds that have melted and bubbled in and out of existence throughout his filmography with the blown out, wide-angle digital tapestries of contemporary surveillance. Didn't know he had this in him; of course abstractly you can place him alongside Farocki in terms of being a weaver and remixer of archival material, but rarely if ever has he crafted anything so contemporary, crisp, and chaotic, Farockian yet leaning away from his didacticism and more toward the symphonic: Morrison's own touch. What he renders almost feels unreal, like fictional found footage, in its perfect narrativity—is it possible that something so sick, and illicit, isn't manufactured? No, this is reality. Reality IS, in a world of surveillance and militarized police forces, a reality that first exists, then a split second later must be manufactured, narrativized, spun. The body cam doesn't eliminate the evil but makes it evolve to act and think more quickly.

An apt point, well framed. Which in turn reminded Morrison of a postscript he recently asked The New Yorker to append to the essay they have accompanying their presentation of the Incident video:

After the film was completed, in December, 2023, the City of Chicago reached a new collective bargaining agreement with the Fraternal Order of the Police. A provision of the contract, ratified by the Chicago City Council, states that body-worn cameras will no longer be used in any post-incident conversations between Department members, and upon review, that such a recording may be deleted upon determination that the recording is not a public record and therefore not required to be maintained.

As Bill went on to note, though actual implementation of this new policy is currently pending an appeal in Federal Court, had it been in effect at the time, both his film and likely the entire Invisible Institute/Forensic Architecture project would have been rendered impossible, as for that matter would much of the public accountability rationale behind the whole body-worn camera program. Which of course is the whole idea.

It never ends.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.