October 27, 2022 : Issue #28

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

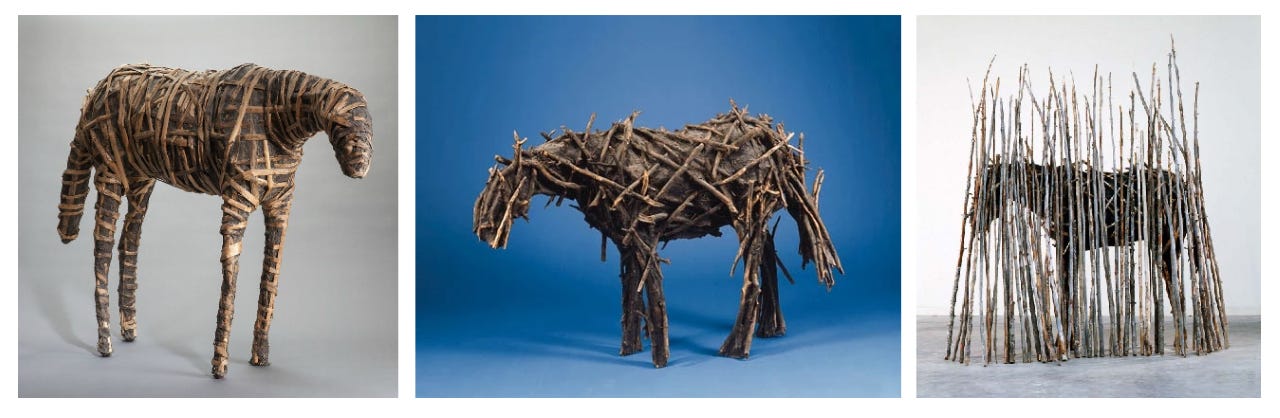

We start this week with an intertwined pair of heaven-sent convergences, before going on to a long-form profile of veteran bronzed-driftwood horse sculptor Deborah Butterfield, on the eve of her next big New York City show…

* * *

For Starters:

A pair of heaven-sent convergences

One morning while visiting Madrid last week, I logged on for my regular morning fix from the This is Collosal website (a habit I thoroughly recommend), where they happened to be featuring a truly astonishing selections of winners from the recent Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition, and one in particular snagged my eye: Dr. Igor Siwanowicz’s honorable-mention-winning vantage on a detail from the radula (“the rasping tongue”) of a marine snail from the Turbinadae family. (Who knew marine sea snails even had tongues, let alone rasping ones—and I ask that question notwithstanding my own status as a veteran UCSC Banana Slug in good standing—not to speak of protuberances of such jaw-dropping kaleidoscopic pulchritude?) (Not, presumably, that they have jaws.)

Such an image at any rate stays with one, or did with me anyway, as I proceeded about my day, presently through the halls of the Prado, past the Velasquezes and the Goyas, the Zurbarans and the Bosches—good lord, the staggering riches of that place!—on through to this Annunciation by Fra Angelico,

which somehow drew me in, closer and closer, something about that angel’s wing, and then of course it hit me:

Which is to say what, exactly? Surely Fra Angelico would have had no way of knowing about the fine microscopic detail of a sea snail’s rasping tongue, and though the good Dr Siwanowicz may well have seen his fair share of Fra Angelicos, thereby having become accustomed to a certain way of looking and seeing, somehow I doubt he ever got that close up to this particular Annunciation (for one thing, as I can testify from personal experience, the guards really don’t like you doing so). Though I may be wrong and would love to stand corrected. Maybe it’s just a coincidence, the sort of apophenia to which I admit to being more than occasionally prone (see Issue #12 of this Wondercabinet series, and its taxonomic sequelae.) On the other hand, maybe there are only so many ways nature has of packing in arrays of stacked scales, feathered or otherwise. (See Issue #13). Then again, this particular angel’s having been dispatched to deliver the word (the annunciation) of God’s imminent intentions, perhaps it’s not so surprising that his wings should partake of the very texture of a tongue.

Or anyway, so I found myself thrumming as I proceeded further along in my day, which culminated with dinner at dear friends of my wife’s and mine, grandparents of a certain age (our own) who happened that evening to be entertaining as well a visitation by their darling granddaughter Julieta, who at one point found herself seated directly beneath a solitary antique eighteenth-century tile with which our hosts had long been adorning their living room wall. We took it down to show to her.

And talk about angels!

* * *

The Main Event

Deborah Butterfield in Walla Walla:

Animal, Vegetable, Mineral

Speaking of splendid creatures and their creators, this coming week is going to see the opening of the inaugural exhibition of veteran artist Deborah Butterfield at her new New York City home, the Marlborough Gallery in Chelsea. The directors there asked me to go out west to interview her for the occasion, and here follows a slightly expanded version of the piece which will be appearing in the exhibition catalog. (As it happens, this is my second such conversation with Butterfield: we also collaborated on a catalog for her 2009 show at the LA Louver Gallery.) The Marlborough show will be up November 3 through January 14, 2023, and the lavishly illustrated 160-page catalog will be available from the Gallery.

I.

Deborah Butterfield likes to say that she was born in 1949 on the day of the Kentucky Derby, won that year by Ponder, who was sired by Pensive, all of which seems almost too perfect. She’s likely to go on as to how she was adopted from infancy into a not particularly horsey though thoroughly loving Christian Scientist family who raised her in a conventional lower middle class tract neighborhood in San Diego, but how one day early on while out on a walk with her father, they came upon one of those little traveling kiddie horse-ride operations. “It was the first time I ever saw a horse, and even though it was likely just a pony, I just knew: it perfectly filled a pony-sized hole in my existence.”

At UC Davis (where she joined the nascent art program helmed by the likes of Robert Arneson, Wayne Thiebaud, Manuel Neri, William Wiley, and Roy De Forest), she managed to secure lodging at an outlying thoroughbred farm in exchange for taking care of the horses. It was a dream situation.

She started out in pottery but soon found herself making horses with metal armatures slathered over with mud (or mud darkened with India ink, to be exact), a sort of tribute to the animist New Guinea mud masks and sculptures she’d encountered in class. Sometimes, for structural support, she A-framed the creatures with rows of long narrow tree branches, tipi style.

Gradually she became more and more interested in the underlying support, the scrap metal armature (“The mud just came to feel like it was icing on the cake, it wasn’t needed”).

In 1976, when Butterfield and her artist husband John Buck moved to Bozeman, Montana, to teach at Montana State University, she began fashioning the horses out of pieces of mountain driftwood she’d scavenged in the hills. She had her first shows at Zolla/Lieberman Gallery in Chicago and Hansen-Fuller Gallery in San Francisco. Then she got a lucky break in 1978, when she was offered a one-woman show by Ivan Karp’s trend-setting O.K. Harris Gallery in New York, which proved a smashing success, and she was soon being widely collected.

“I was making these incredibly fragile things,” she recently recalled of those early days. “The small pieces especially were just sticks wired together, and the wood would shrink, the wire would stretch, the cat would knock it off the piano. And when I would go see the work in collectors’ homes it looked like roadkill. I had a traveling show that went to twelve museums, and collectors of mine in the various cities where I would be installing the work would say, ‘Oh, let's have a cocktail party for you.’ And I would end up spending the entire night on the floor with pliers, trying to fix those things. I did what I could, but I got so tired of that, because I just don’t have the temperament for carefully repairing things. I began to worry: Was I going to have to be doing that for the rest of my life? So that's what led me to bronze really. I realized the color might change, but at least in a hundred years, somebody might still know my intention in terms of the form.”

By 1987, Martin Friedman at the Walker Art Center had commissioned one of her large wooden projects to be transformed into bronze for the Sculpture Garden he was beginning to build there in Minneapolis.

That was the piece that first brought Butterfield to Walla Walla, a small foundry in eastern Washington state that she’d begun hearing about from such fellow artists as Jim Dine and Manuel Neri which had only been launched a few years earlier by locals Mark and Patty Anderson. “Mark came up to Bozeman, and our first son Wilder had just been born, so it was 1984, I guess. And he looked at my slide talk and said, ‘Yeah, you gotta drive down a truckload of sticks and we'll cast them in bronze and weld a piece out of it’ and that's how we worked for quite a few years. It was the most fun I’d ever had.”

She’d bring sticks into her studio and slowly fashion them into horses, fragile structures which she would then drive over to Walla Walla, where Mark and his crew would painstakingly photo-document and then dismantle the sculptures, individually casting the branches, one at a time, into identical bronzes (the wood itself having been systematically burned to ash in the process), tooling and finishing each segment and then welding the entire sculpture back together on the far side, finessing the welds and sandblasting the whole thing, at which point Butterfield would come down again and join them for the final touches.

*

Nowadays, almost forty years on, the Walla Walla operation has grown into one of the most massive such artist-support foundries in the world—a good dozen huge hanger-sized buildings manned by over one hundred exquisitely trained artisans,

in the middle of which, just off to the side, anyway, a small one-bedroom and kitchenette apartment abutting a tall hanger studio space of its own constitutes the heart of Butterfield’s own private compound. Just across the driveway, there’s a vast acres-wide greenhouse, entirely given over to carefully archived piles of her collected driftwood. (“And I know where every single piece is,” she boasts.“I just have that kind of mind.”) One of the longest-term veterans of the foundry, she is these days fashioning the lion’s share of new work right here on site.

The other day, after we completed a gobsmacking tour of the whole facility, Butterfield and I ambled over to her studio where we found three of the bronzed pieces destined for this current Marlborough show, standing, as it were, at ease, each of them covered over in a ghostly beige paint undercoat in stolid anticipation of the coming application of their patina finish. Over to the side, on a tabletop plinth, stood a new medium-sized wooden piece which Butterfield had transported in the backseat of her car on the nine-hour drive down from Bozeman the day before.

And it was a beauty, albeit a harrowing one, for it had been fashioned out of sticks pitch-blackened in the recent spate of wildfires, still gleaming in the crazed liquefied sap of the expiring tree. I leaned in to examine the minute craquelure of the burnt bark. “I know,” Deborah said, “terrible how beautiful it is, the riot of feeling it arouses, terror to be sure at all these rampaging fires, and yet…”

I mentioned how a friend of mine had taken to calling the latest phase of the Anthropocene “the Pyrocene.”

“Exactly,” Butterfield concurred. “And I just find myself being consumed by gr—”

I know, I said, by grief.

“Actually, no” she said, “I was going to say, by greed. Greed and lust. I know: I’m a really bad person. I heard about those god-awful floods rampaging through the canyons leading into Yellowstone a few months ago, and as much as I felt for those people in the little towns all around, and for that matter for all the rest of us because of the horrible times ahead that those calamities portend, still, all I could think of is how avid I was to be getting down there, to scavenge among all that mangled driftwood. The force of all that water and the shapes it will have scoured!”

Beauty is just the beginning of a terror we can only just barely endure, I quoted at her, and we admire it so because it calmly disdains to destroy us.

“Wow. Who said that?”

Rilke, at the outset of his Duino Elegies. “Every angel is terrible.”

“That’s amazing. Make sure to include it in your piece.”

She leaned into her blackened mare. “Look at the detail in there. That craze of tiny cracks along that branch. Hard to believe that those guys will be able to capture it when they set the thing to bronze. But they will. They’re really good.”

She stepped back for a moment, evaluated the lee of the hind legs. “Hmm,” she said. “Something’s gone wrong with the left leg there, it’s gotten twisted, probably on the ride down.”

She reached in and started dragging the limb back and forth at the knee, incredibly forcefully. “Hmm,” she repeated as she walked over to a nearby tool chest, returning with a mini handheld Japanese saw, wedged it into the offending joint and cut it clean through, carrying the amputated foreleg over to another chest and returning with a glue gun, a pair of chopsticks, and some bailing wire. “I know,” she said, “brutal. But sometimes that’s how it goes.”

I’d seen this same thing though with other artists, the way that right up to the completion of the piece they can be incredibly curt and violent with their own work, in a way that a few weeks later, gallerists and conservators and collectors would never dream of being with the completed object.

Looking back over at the three prepped pieces in the middle of the room, I asked her if she enjoys doing the final color work.

“Not really,” she said, much to my surprise. “I just wasn’t trained as a painter,” she clarified, “and it’s very difficult for me. Sometimes I do love it. It's like Mickey the Sorcerer's Apprentice. There are some days I come in and the chemicals and the torch, everything, is just so much fun. And there are others where I cannot do one thing right. And then I accuse my assistants of having a more concentrated version of the ferric nitrate. But then I found out that in many cases it was true. I'd be working for hours to get this red blush just right whereas they'd just be spraying it on and it was happening. And so that's when I started mixing my own chemicals, because the reason I wasn't getting anywhere is that I didn't have enough ferric in the water solution. Bronze-worker’s version of secret glaze formulas!

“Here,” she said, “I’ll show you.”

She grabbed a blowtorch, reached into her back pocket for a sparker, lit the thing, and aimed the fierce blue flame at the haunch of one of the horses. Actually, I noticed that it was already a little colored, and she explained how she’d already started the previous night when she got in. “You have to heat the metal itself, get it good and hot, and then”—she reached over to a side table and grabbed a spray bottle filled with a sloshy dirty-orangish brew—“you spray or paint on the patina, ferric acid in this case, which is basically rust mixed in a water and nitric acid base which lays in a sort of reddish coloration”—she stopped spraying and applied the roaring blue flame once again—“back and forth, spray and flame, spray and flame. The heat makes the color bond to the metal. And if you want a darker coloration, you apply liver of sulfur, otherwise known in chemistry labs as sulfurated potash, but we’re all artisans here, as the guys like to say, and we prefer ‘liver of sulfur.’

”But again, I struggle with it, getting the combination of the heat and the admixture right. What’s right for one passage won’t be for the next. And then I often don't know what I want. It isn’t just aiming for an exact replication of the original wood itself. It's trying for a kind of poetic justice, finding the nature of the original wood, but somehow tying everything together at same time, so that the overall outline and the composition of the piece as a whole makes sense visually, color-wise. The color is very much part of the emotion of the piece, as with any painting, and it takes a long time. Only, here you have to do it 360 degrees. It's not just a flat thing, you have to get underneath it, on top of it, in front and in back and on each side. And it's exhausting and complicated; it's a puzzle.”

But it was interesting what she’d just said, that it wasn’t simply a question of trying to achieve an exact replication of the original branch, that over and beyond that—well, as the saying goes, "Making the real real is art's job."

“Exactly,” Butterfield concurred, “Eudora Welty.”

I commented on how layered the process seemed, you had the heat, the spray, the paint, all those sorts of variables, the different textures you were aiming at, and all the other different kinds of things going on.

“Yeah,” Butterfield agreed, “It's very AE.”

AE?

“Abstract expressionist. I mean, it really is a very physical gestural thing on these big pieces, but I do enjoy the color on them way more than on the small pieces. Those are the ones that really get me. I can do the big ones faster, work from my shoulder and not just my wrist.”

She extinguished the blowtorch and set aside the spray bottle. “That’s enough for now,” she said. “We’ll be doing this for days. But let’s go back into the apartment and get a drink.”

II.

She grabbed a couple seltzer cans from out of the refrigerator, we sat down on the couch, and she turned on the TV to check in on the January 6th committee hearing. And it was uncanny.

“What’s with that Butterfield horse there in the background?” we both gasped, simultaneously.

The hearings lumbered on, the republic kept tottering. But there was nothing we were going to be able to do about it in the short term, so we turned off the TV. I asked Deborah if she’d mind if I turned on my tape recorder, and she said she wouldn’t. So I did:

WESCHLER: I wanted to talk to you about why you only do horses.

BUTTERFIELD: When I first began making the horses, if anything I faced all this pressure in the opposite direction: not to be making something as old-fashioned and seemingly tapped-out as horses, to do something different. At the time I remember thinking, “Well, nobody else is going to be interested in this in a few years but I’m doing it anyway.” So, it was the opposite of a commercial decision. I mean, initially, it never occurred to my husband or me that we would actually sell art or that if we did, we’d be able to afford to live off of it. We figured teaching would have to be our primary source of income.

As regards the other, I’m sure that there are people who are totally bored by my work and that’s okay, but I have to say something for the value of boredom. I guess I’ve found that boredom is something that I remember fondly from my childhood. Those long days I spent alone with my cat were some of the best times of my life. I think today that we fill our time with so many things: computers and the 24-hour news cycle and Trump and all have just made it worse. And I try to deal with that within this crazy world by being with my horse or in my studio where nothing else exists at that moment.

WESCHLER: Time out of time.

BUTTERFIELD: Time out of time. Where I can just be this organism that is truly responsive in that moment. Of course, it’s totally artificial. But fear of boredom is the least of it.

WESCHLER: Of course, there are other ways of looking at that immersive choice. For instance, there’s the example of Morandi.

BUTTERFIELD: I love Morandi! He was a huge presence among the artists up in Davis, we all idolized him.

WESCHLER: Interesting: the same with the Ferus artists down in Los Angeles. Indeed, Ferus mounted one of the first gallery shows of Morandi in the U.S., back in the early sixties. And sure, you could say that all he was doing was those same damn cups and bottles on that Bologna studio tabletop repeatedly, ad nauseum, his entire life. But in fact, each new canvas, decade after decade, proved a fresh exploration of the physics of presence, the play of light and perception, the cups and bottles providing the merest occasion. That’s the sense in which Bob Irwin considers Morandi to have been the sole successful European abstract expressionist.

BUTTERFIELD: Absolutely. Beyond that, it was as if Morandi, by his example, was giving a kind of permission.

WESCHLER: It seems to me that if anything, Morandi was practicing what Kierkegaard, in his “Rotation Method,” characterized as the depth of experience afforded by self-limitation. That was certainly true of Morandi and may well be true of your career as well.

BUTTERFIELD: I hope so—at least, that is how I experience it.

WESCHLER: Another way of putting it: there’s a famous Greek fragment where the Pre-Socratic philosopher Archilochus says that the fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one deep thing.

BUTTERFIELD: That’s me.

WESCHLER: You’re the hedgehog?

BUTTERFIELD: I am.

WESCHLER: Isaiah Berlin cited that fragment in a celebrated essay about Tolstoy, in which he asked whether Tolstoy, particularly with regard to his treatment of history, was more of a fox or a hedgehog. And what Berlin said about Tolstoy seems to me to apply to you as well. In that, whereas superficially you’re a hedgehog, I think you’re actually quite foxy.

BUTTERFIELD: Why, thank you.

WESCHLER: Well, there’s that, too. But I’m thinking of all kinds of stuff—of experience, of posture, of perspective, of the changing qualities of lived being—all of which you are able to evoke by way of that seemingly narrowly constrained hedgehoggy horse motif of yours.

BUTTERFIELD: Doing it, at any rate, over the years, it certainly doesn’t seem redundant. The challenge remains ever-fresh, as if brand new each time, continually informed by the changing quality of intervening lived experience. And then, too, by experiments with posture and scale.

WESCHLER: That still leaves us with the question, why horses? Why not cows or dogs or cats?

BUTTERFIELD: What’s interesting there is that the dog and the cow, and to some extent the horse and the cat, all offered themselves up for domestication, though I think the cat and the horse, who I’m more interested in—and I actually love cats even more than horses—a horse supposedly can revert to the wild within three weeks and a cat is always on the verge of doing so. So they choose to be with people, whereas dogs and cows have become more dependent on people, in my opinion, and hence less interesting to me. Coming back to cats though: When I was little, there was an issue with my birthdate, so I was held back a year before joining kindergarten, and I must have spent that whole year on my belly, crawling around in the grass with our family cat—and it was one of the best years of my life.

So, why not cats? That’s a good question. I guess maybe it’s a matter of the scale.

WESCHLER: Interesting that horses are roughly the same scale as that cat must have been to preschool you with your face scrunched down there in the grass. Though another issue there would be the problem of their little stumpy legs—not nearly the long easel legs you get with horses.

BUTTERFIELD: Could be, though in the meantime I took to doing small scale horses as well—

WESCHLER: Cat-sized, as it were.

BUTTERFIELD: In some ways, I find those small horses more powerful, somehow more concentrated in their energy, than the big ones.

WESCHLER: Myself, I sometimes think of those tabletop horses of yours as your bonsai horses: fashioned out of miniature twigs which in turn stand in for bigger branches.

BUTTERFIELD: Meanwhile, my full-scale work seems to be getting bigger and bigger, and it’s not that I’m getting more macho. It’s more like what happened with Goya’s astigmatism. I think my handwriting is getting bigger and bigger, too, but it’s just because I’m getting blinder and blinder: it’s still the same scale to me. It’s just that my eyes have changed. I sometimes go and see my old work—the life-size work—and it’s so small and intimate and it’s actually real-horse sized and I’m kind of jealous of that work.

Coming back to your question as to why I do horses, I guess it really does have to do with riding them. I have distinct ongoing relationships with horses that is actually hands-on, every day.

Horses are like the ocean. I mean, they’re extremely civilized and domesticated. They’re very smart—maybe not at doing what people do or what dogs do but they’re really smart at what they do. They’re the best at being horses of anybody. But there is that danger and respect. The idea that at any moment they could kill you. Not that they’d want to. They’re just—they’re forces of nature. It can get to be like a rogue wave: you just never turn your back on the ocean.

But I guess the horses that I’m interested in are the ones that have shown an interest in getting to know me and I’m—I’m just so honored by that. Ed Kienholz used to ask me, “What is it? Do you like the power? That must be it: you just like ordering this big thing around and telling it what to do.” And I was like, no, I like asking it if it would like to join me in moving and having it in turn willingly want to do that. And part of my relationship with my horses—it’s so loving but there’s also… I mean like my old girl Isabel, for the first five years when I got on her, every day, it was “Who’s the boss of me?” It became a joke between us. And just because I had this beautiful dynamic relationship with her didn’t mean that I didn’t have to make boundaries and occasionally get in disagreements with her. It was so hard for me learning how to be the “boss” in a way that allowed her to be herself: to make limits so that she could actually express herself in a more creative way. Of course, I had to do the same with myself.

WESCHLER: Are you talking about horse here or are you talking about art? I ask in part because I remember some of the way you used to talk about some of the power machinery involved, especially in making those scrap metal pieces, the scary amount of coiled energy in some of those snippers and the like. But also because—there’s this great line of the French Enlightenment encyclopedist and art critic Diderot’s where he talks about the moment when the artist stops asking What can I do? and starts asking What can Art do?

BUTTERFIELD: Indeed, those great moments when you really enter the flow, the dance, whether it’s out in my dressage arena up in Bozeman or here in the studio.

WESCHLER: But I want to come back to this business of having been doing the same sort of thing for five decades. How is it different for you today than it was forty years ago?

BUTTERFIELD: Well, I think over thirty or forty years, for starters I've made larger piles! I've been able to gather more and more varied materials. And so I feel that I have a more of a library of material of wood or metal or whatever such that I have more choices. The flip side is that I feel some of my early work was so wonderful because I had such limited choices. And now that I have more choices, in many ways it's harder.

On the other hand, I also have more mastery: it just builds up, over the years, that you have more experience not only at looking at things, but just building things. And even though I'm older, I feel like in many ways I'm stronger or just more skilled at moving things. The foundry workers are always saying, “Oh, let somebody help you with that.” And part of my great joy is lifting the bronze or the wood, knowing how to balance it, and feeling it and almost listening to it and waiting to know, to hear, where it goes. I have this great joy of especially different kinds of wood, you know how they all have different qualities, different histories.

I should say, incidentally, that yes, while I am obviously a horse person, I am every bit as much, and in recent years maybe even more so, a tree person. I am completely captivated by the physicality and narrative that wood presents.

WESCHLER: And for that matter, I suppose, of transformation itself. Branch into Horse into Bronze. Vegetable, Animal, and Mineral. And back again.

BUTTERFIELD: And yes, mineral as well. Here in Walla Walla, of course, I'm dealing mostly with the cast bronze—I don't believe I have any welded steel pieces in this coming show—but with the bronze sticks and having had great assistants, you know, we could take anything, we could cut pieces out of an almost finished piece, reweld it, bend it, weld the places where it had cracked…Part of the joy of working with bronze is that it is very malleable. It will let you do what you want with it. And the fact that I'm not making editions of these big pieces, I can come back and change my mind. We can cut a whole neck and head off, and I have a stock of armature material so I can refabricate things. That’s part of the mastery, I suppose, the sense of becoming more comfortable with erasing.

And then having people who can make it happen is pretty fabulous, which of course is part of the advantage of a later career, because it can get very expensive, and you don’t have that sort of backing at the beginning. And being able now to have this studio of my own here in Walla Walla: I can just walk out of the apartment at night and grab something if it catches my eye and I'm allowed to go and fix it or wreck it, or whatever. And so, I do feel these days, I'm able to live with the evolving pieces more, which maybe gives them a little more substance somehow. Emotional substance, perhaps.

And then, too, I think that over the passing years, I’ve become more and more interested in manipulating the negative space, especially within the central armature which as a result feels like it’s opened out more, there’s more air, which means more breath, more life, perhaps.

WESCHLER: It’s interesting that you put it that way, because I was going to ask if now, forty years on, if there is more a sense of impending mortality, whereas at the outset of your career, you were young and your relationship with your horses was new, you were all starting out together, you were opening out on life and having kids and so forth.

BUTTERFIELD: There’s liveliness and airiness in that space. It’s both the grief that occasionally informs the making, but also the sheer and vivid joy that comes with the making itself: the composition, the space between, the negative space that kind of allows you to crawl in there. I think it's about finding some kind of silence. I can't quite describe it, but there is a meditative devotional quality to the work. And that's where I am when I'm making it.

From the very beginning of my art making, though, loss was everywhere. My best friend died when I was twenty-one. And my father died when I was twenty-six, way too soon. I guess I just knew that people leave without any warning, and of course, animals, you know that they're going to leave, but often they also leave too soon without warning and you're just never ready.

It’s such a lesson in impermanence and enjoying each moment. The pain that you go through when they leave: just the volume of their loss. It leaves a hole in the force, this vacuum that’s then there for quite a long time, interrupting the flow of everything.

I can’t emphasize enough, though, how the making itself for the longest stretch remains an abstract activity, and very much material based. Eventually it ends up being a horse, but it really doesn't start out being a horse.

It's this rectangle on four legs and I stuff it full of this composition that's reacting to the material, the weight of it, the mass, the volume, the surface, the motion in it. And so I come up with this composition and as you've seen, I can be very brutal with it. But it's very ‘not a horse’. It's not sad. It's really only towards the end when I add a neck and head and all of a sudden this abstract composition informs me as to who it is that then it becomes personified, and it's then that it becomes emotional. It's like being a surgeon, or a veterinarian: in order to do your job, you do have to be able to step back and become....

WESCHLER: Well, you have to have a passionate equivalence.

BUTTERFIELD: Exactly. That’s a good phrase.

WESCHLER: Which in turn reminds me, speaking of negative space, of the poet John Keats’s notion of negative capability, this capacity which he talked about in some of his letters, and very famously so among literary critics, about—I'm gonna mangle this a little bit—but the capacity in great artists, with Shakespeare being the prime example, of their being able to lounge in contradiction without the irritable grasping after certainties.

BUTTERFIELD: Wow. That's lovely.

WESCHLER: And it seems to me that that may have something to do with the coexistence in your work of grief and joy.

BUTTERFIELD: Mm-hmm

WESCHLER: But I still want to try to talk about the difference between doing this kind of art when you're 30—

BUTTERFIELD: Oh, I see what you're saying.

WESCHLER: —and when you're—

BUTTERFIELD: Seventy-three.

WESCHLER: —when you're 73, okay, to take a number at random. And I just want try this out: When you were 30, the sense of mortality you had was as regards others (your friend, your father, occasional horses), but that now (you are 73, I am 70) the breath of mortality—

BUTTERFIELD: Everybody is dying all around you—for starters, all of the teachers. My own masters: Robert Arneson and Roy DeForest and Hung Liu, a while back, and more recently Manuel Neri, William Wiley, and just the other day Wayne Thiebaud. And of course Mark Anderson here at the Foundry a few years ago.

WESCHLER: For years now, I’ve had this sense of the upper canopy gradually clearing out such that the full glare of mortality starts to fall on those of us in the middle story down below.

BUTTERFIELD: Nice tree metaphor there. But yeah, you’re saying, soon it’s going to be me.

WESCHLER: Well…

BUTTERFIELD: Actually, it’s more the world itself that I am grieving for these days, and our own role in its coming…

WESCHLER: And how does that get reflected in your work now, I guess is what I am trying to get at.

BUTTERFIELD: {Extravagant exhausted sigh} Ren: Just tell me what you want me to say! {laughs}

WESCHLER: I don't want you to say something you don't believe, but—

BUTTERFIELD: I don't know what I want, why do you think I'm still doing this?.

WESCHLER: There's that great line of E.M. Forster’s: How can I know what I think till I see what I say?

BUTTERFIELD: That's it!

WESCHLER: Well, if I want to see what you say if I keep prodding you in a certain direction, it's because... I guess I'm trying to ask, we're coming back to how it is different for you today to be doing this than it was when you did the piece about your father. When instead the shadow of mortality falls over—

BUTTERFIELD: Oneself. Myself.

WESCHLER: Just looking at you: your face is weathered as is your whole body, and yet it's that same combination of incredibly beautiful, but it's also steeped in, shadowed by mortality.

BUTTERFIELD: Well, it's a bummer. I'll tell you. {laughter}

WESCHLER: Well, it's a bummer and it's not.

BUTTERFIELD: But it is. You mourn the loss: once you finally figure out how to manage your body and somewhat your mind, it becomes worn out and old. And that part, I have a lot of regret about that. It isn't just a beauty thing. It's like, dang, I wish I’d had it together earlier. But there is this joy and gratitude that I'm still able to do what I can do. The joy of moving and being in the woods and gathering sticks and being able to drive down here to Walla Walla and getting to work with other people, it is a joyful thing. When I'm doing that and in my studio, I don't think about the other stuff.

WESCHLER: Let me try this other way of thinking about it. One of the things that's interesting about you, as we’ve discussed, is how you don't want to leave your work just as wood, because it will fall apart and so forth...

BUTTERFIELD: Right.

WESCHLER: ...just like we do. And so you put it in bronze, which makes it permanent. To what extent has there always been, with your work in particular, this aspect of attempting to transcend the inevitability of death?

BUTTERFIELD: {long pause, deep breath} I guess when I was really little and they were reading Bible stories to us in Christian Science Sunday school, they talked about the Golden Calf idol.

And being a Taurus, I thought it was so wonderful and I couldn't understand what was wrong with it. {laughter}

WESCHLER: So that was the end of a certain kind of religion for you?

BUTTERFIELD: {laughter} God, I suppose so. But I think, besides being a horse and tree worshiper, I'm just an animist. And maybe it's just as simple as that. I love rocks, too.

WESCHLER: An animist is content to just let dust go back to dust, but you are turning it into bronze.

BUTTERFIELD: Right.

WESCHLER: By the way, the Golden Calf was the bronze of its time. It was gold, but the point is it wasn't going to disintegrate. And you are in a certain sense, life against death, you are re-casting this organic material into...

BUTTERFIELD: Putting it in the tree museum, as Joni Mitchell would say.

WESCHLER: But not as trees. As bronzes of trees. All of that activity in the Foundry is designed to push off the fact that the stuff that the artist is working on, while valuable, is destined to disintegrate, and theirs is an attempt to keep that from happening.

BUTTERFIELD: But I haven't even really thought about it being here beyond my death. Honest to God, I really haven't. I don't really think like that. All I want is to not go to someone's house and have one of my old stick pieces look like roadkill. I mean, I just want people to see what I intended them to see. And I just don't think about immortality, I'm not interested. I really am more about the moment. Mainly there is this joy and gratitude that I'm still able to do what I can do. When I'm doing that and am in my studio, I try not to think about the other stuff.

And as for the bronze, you know, it's still alive. It's always changing, it's oxidizing. The color won't always be as I intended. The sticks are like three-dimensional brush strokes. And there is an emotion and an energy that's almost like an x-ray of a given moment. It may not have anything to do with the horse really, but the horse is my container for those feelings. It's like a vessel that contains that kind of energy. I started out as a potter, and in a sense that’s what I still am: a maker of vessels.

WESCHLER: It’s funny: patina and painting are almost anagrams of each other. But when you are laying in the patina, you want it to be just good enough to call attention, once again, to the structure and the air and the negative spaces, all of that, but not have the virtuosity of the effect get in the way.

BUTTERFIELD: H.C. Westermann’s pieces were very much about virtuosity sufficient to serve ideas, just like Magritte: but they weren’t trompe l’oeil, they didn’t need to be absolutely exact to carry over the idea, just good enough.

WESCHLER: And yours?

BUTTERFIELD: I hope so. Magritte and Westermann, they were both more narrative. Ironic, funny. And my horse is not quite such a narrative idea. But to me, the narrative is in the sense of the journey of the wood or the metal or whatever material I found that leads us to that point. But it's not a narrative that's in words.

WESCHLER: The other day at the Seattle airport, you were telling me, some kids, coming upon your piece there were excitedly saying, “Look, it's made out of wood!”

I assume it doesn't bother you if people don't realize it's actually made out of bronze.

BUTTERFIELD: It doesn't. I think it's so refreshing. It means I've done my job.

WESCHLER: What do you imagine that the ideal owner of a piece of yours is in terms of how it exists in their lives? They didn't make it, so they don't have that muscle memory.

BUTTERFIELD: Ideally, the piece becomes a touchstone. I hope by standing next to them you can understand them and feel their energy through your skin. They are quiet and reflect you back on yourself. They are a safe spot to observe things from and, if you are like our cats who live in the reclining sculpture outside our barn in Bozeman, it is a spot from which to wait for birds. Spiders and birds like to live in them, and wasps. I mean, I guess I feel honored that other species seem to appreciate them. Though many woodpeckers have hurt themselves—

WESCHLER: Is that true?

BUTTERFIELD: Oh yes.

WESCHLER: That’s literally the old Zuexis trope come to life, the fifth century BC Greek master painter whose murals of grapes were so vivid that birds were said to fly down to try to snatch them, so great was their presence.

BUTTERFIELD: Which I think is what we all need, a presence. Which is why I almost prefer them indoors, playing off the wall, the enclosure, but radiating, as you say, that sense of presence. We're all too busy doing so many stupid things. You know, I practiced karate. I practice dressage. And I guess my whole life is devoted to just trying to slow things down so that we can be in the present.

III.

While Butterfield excused herself to freshen up before dinner, my own attention returned to the three ghostily prepped horses arrayed back in the adjoining studio in the gathering dusk.

Most horse artists tend to cast their creatures in the vividness of action—strutting, rearing up, lunging forward: arrested snap shots plucked from hurtling time. Whereas Butterfield, it occurred to me, always seems to present her horses in moments of stilled repose, just standing or lying there, consumed in their own horsey thoughts, as time passes.

Like Vermeer’s women, who are always posed in the midst of having to stand still for some reason (to assay a balance, to pour milk, to read a letter, or evaluate a necklace in a mirror), Butterfield’s horses are not trapped in the immediate present tense: rather, they are, yes, themselves emblems of presence, of duration. Which is to say, paradoxically, for all their calm, they are perhaps more vividly alive. They are not performing for us or even looking over at us, they seem heedless of our presence, which is also key to the effect.

Butterfield now rejoined me in the studio, tamping down her washed hair with a towel. “I sit astride life like a bad rider on a horse,” she seemed to quote. “I only owe it to the horse’s good nature that I am not thrown off at this very moment.”

Who said that? I asked

Wittgenstein.

“Philosophy unties knots in our thinking, hence its results will be simple,” I counter-quoted the Viennese master, in lines that applied as well, I suspect, to a certain sort of artmaking. “But philosophizing has to be as complicated as the knots it unties.”

Touché, Butterfield parried.

I tried out on her my notion about how her horses never seem to be looking over at us, lounging as they do in the sovereign amplitude of their own sheer horsiness.

“Actually,” she corrected, “horses are in fact taking you in: their eyes are on the side of their heads. Unlike carnivores who focus frontally, horses have nearly 360-degree vision. They are prey animals. They are often looking at you sideways.

WESCHLER: That’s interesting, though I don’t think most people realize that. Most people think that the horse is looking at what it’s facing, and hence, in looking at your horses, they have the experience of a creature momentarily oblivious to themselves.

BUTTERFIELD: Where you’re right, I think, is that horses are more Zen than that. They’re aware but not aware. They’re like the moon, they notice you, but they don’t necessarily care.

WESCHLER: And I guess my point is that in the dance of projection and counter-projection that you’re having, that horse is so lifelike, that horse really is like it’s in a field, and it couldn’t give a damn about you.

BUTTERFIELD: “Is there a God? Does that God love me or is God just the majesty of gravity?” And, to me, that’s what it is. It cares in the sense that it’s also wonderful and grand, but really it is so impermanent. Here today, gone tomorrow.

WESCHLER: So, you are a religious sculptor after all. In his essay on you in the Abrams monograph, John Yau had a great line where he quotes this one professor to the effect that when the 8th century Chinese master Han Kan painted horses, he truly was a horse. But it strikes me that your work actually takes things a bit further. If you only sculpted trees, this likely wouldn’t happen—and it doesn’t happen with military horses or Remingtons rearing up—but when Butterfield fashions horses out of trees, somehow this play of leapfrogging projections kicks in, such that when Butterfield makes horses, you the viewer becomes the horse.

BUTTERFIELD: Now look: You’re making me cry.

But yeah, that’s what I’m hoping for: That people might leave their own identity for a moment and crawl into this other being that doesn’t have a way of understanding through language. That for a moment you could be without words, you’d have to just shut up and listen and look.

WESCHLER: Because, after all, to borrow a phrase, seeing is forgetting the name of the thing one sees.

*

That last being Paul Valery, of course, though it also happens to be the title of my own book on Robert Irwin. Meanwhile though, for those of you who might like to purchase that 160-page lavishly illustrated Marlborough catalog at a 20% Wondercabineteers discount, you can do so through the end of November here by including the promo code Butterfield-2022 as you check out.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

The Animal Mitchell archive.

***

NEXT ISSUE

On the immediate far side of the coming mid-term elections (and come on, everyone, let’s get out there and VOTE!), the story of Bruce Beasley, the veteran West Oakland abstract sculptor who wants to make the case for being politically engaged in one’s life independent of one’s art, or at any rate expansively alongside that art rather than narrowly so focused within it. And more…