WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This week, some attempts to put the current Israeli-Palestinian carnage in a wider historical context, and tendrils of hope on the far side, arising from that very sense of deep history.

* * *

SOME TAPROOTS OF CURRENT EVENTS

There have, alas, been no end of dirges, alarms and commentariatribes on events in the Middle East since the dreadful events and counter-responses beginning earlier this month with Hamas’s lightning attack on Israel. But the lines that kept thrumming through my own head, the ones that seemed most trenchant and pertinent, date back from well before that, back to the hours immediately after Hitler’s blitzkrieg invasion of Poland at the start of the Second World War, with W.H. Auden hunched dismal at a bar in far-off New York City: the opening stanzas of his “September 1, 1939”:

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

That last couplet in particular: so simple and so obvious, cutting clear through all the other commentary. Strange, too, its tolling relevance. How in immediate terms, Auden seemed to have been referring to the way the peace at Versailles that had concluded the First World War had so egregiously victimized the Germans that now they seemed set on victimizing everyone else—in particular of course the Jews, whose shattered remnant, horrendously done-in, would subsequently set to victimizing the Palestinians, a segment of whom now seemed dead-set on doing their own evil in return, with the Israelis responding in kind. Where and how might it ever end?

Such thoughts in turn had me returning to a piece I wrote almost a “low dishonest decade” ago, the last of a triptych of such pieces I’d composed at the time in response to Israel’s then-most recent attacks on Gaza (a fifty-day siege in mid-summer 2014 which had resulted in 2,251 deaths on the Palestinian side, compared to 74 on the Israeli—a fairly standard outcome as such confrontations used to go, until only just recently, though we are hardly at the end of the current round, so who knows where this one’s grim tally will finally land). My own thoughts on that occasion, as it happened, stretched well past Versailles.

* * *

FROM THE ARCHIVE

SARAJEVO 1914 / GAZA 2014:

THE SHORT TWENTIETH CENTURY LINGERS ON

Truthdig, August 4, 2014

Strange the way things line up, the through-lines that suddenly reveal themselves amidst the twists and turns of historical progression.

Last month, in these pages, I was writing about the ways in which Israel’s ongoing treatment of Gaza and the Palestinians cooped up therein (the strangulating siege, the warehoused concentration-camp-like conditions, the regularly recurrent assaults, the lopsided carnage) put me in mind, not so much of the fate of the Jews and gays and Gypsies in Dachau or the Warsaw Ghetto in the years before the Final Solution, or the Afrikaners under the British during the Boer War, or the Sowetans under apartheid, or the Japanese-Americans in their World War II internment camps (all analogies regularly invoked both by me and others), as that faced by the residents of Sarajevo during the terrible 1,500 days of their siege and bombardment by the Bosnian Serbs from 1992 through 1995.

And then furthermore, come to have thought of it, how uncannily the obfuscations and protestations and delusionally heightened sense of grievance regularly expressed by many Israelis (and even more so by their American apologists) reminded me of the sorts of “bugs in the software,” the “brain damage,” the momentary episodes of slippage I’d so frequently encountered among otherwise quite sensible and civilized Serbians in Belgrade during that same period just after the recent Bosnian War.

Some people liked the analogy, others didn’t, but in the meantime I myself, this past week, have found myself falling clear through that historical parallel and down through the years to that other, or rather that earlier Sarajevo, the site in 1914 of the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife by the Serb nationalist fanatic Gavrilo Princip,

one hundred years ago this past June 28, the event that set the gears in seemingly inexorable motion toward the launch of actual hostilities exactly one hundred years ago this week as World War I brought a horrendous Niagara-like (Henry James’ image) conclusion to the nearly 100 years of relative peace on the European continent (since the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo in June of 1815), and, in turn, launched the harrowing succession of decades that were to follow, dark-blasting so much of the rest of the 20th century.

More specifically, I’ve been thinking about the way historians over the last few decades have regularly taken to speaking of the Long 19th Century (by which they mean the years from the French Revolution of 1789 through the start of the First World War in 1914) and the Short 20th Century (from 1914 through the remarkable succession of largely nonviolent revolutions that brought about the downfall of communism in 1989). That 1789/1989 rhyme is indeed quite remarkably uncanny, but no less so than the manner whereby so many of the historical processes set in motion in 1914 did indeed seem, finally, to resolve themselves in 1989. The braiding in particular of the rise and fall of the twin totalitarian scourges launched by the catastrophes of that First World War: the way Bolshevism was able to overthrow the ages-old Imperial order in Russia in 1917 as a direct result of the latter’s calamitous failures on the Eastern Front, but also the way that the rise of Nazism proved a direct result (directly predicted at the time) of the way Germany was mistreated in the grievously misguided peace settlements after 1918. How the inevitability of a Second World War was almost baked into the mix at Versailles, one that would come to pit Bolshevik Russia (and her allies) against Nazi Germany, calving off large swaths of Central and Eastern Europe in the peace that followed and subjecting them to Soviet Russian domination for almost another half-century, that is until successive uprisings in that same (as it turned out, indigestible) periphery came to bring about the downfall of communism in Moscow Central itself, thereby reuniting a transformed and now decidedly more pacific Germany at the heart of a decidedly wiser and more tempered United Europe. Problem solved, Short Century closed.

Except that, it seems to me, it’s becoming more and more clear that that standard account leaves something important out, such that the intricate braidings of the so-called Short Century have in fact yet to play themselves through.

Leave aside such peripheral (albeit paradoxically seminal) problems as what to do with those damn Balkans. (Sarajevo! The place it all started.)

Turn instead to what in retrospect may have proved a whole other strand of historical braiding across the Short Century: the question of what to do with Europe’s Jews.

Granted, the taproots of that dilemma wend well back into the Long Century, generally speaking to the upsurge in anti-Semitism occasioned most immediately by the flood-tide of Jewish assimilationism in the wake of the French Revolution, and more specifically to the ways in which that anti-Semitism initially flared most powerfully in France (partly as a result of the French military’s humiliating defeat at the hands of a surging Germany during their mini-war in 1870) with the appalling Dreyfus affair of 1895 and its various unwindings in the years thereafter. That affair (at first, essentially, a German spy scandal at the heart of the French military command) in turn left two lasting legacies, in terms of the history of braidings we are considering here: It badly damaged French military command cohesion and integrity in the decades leading up to 1914, thereby accounting to some degree for the relative incompetence of the French military response to the German invasion in the first months of the coming war; but more to the point, it (along with the rise to power back in his hometown of Vienna of the rabidly anti-Semitic mayor Karl Luger that same year)

inspired Theodor Herzl, an Austrian journalist in Paris to cover the Affair, to publish the following year his pamphlet Der Judenstaat, the founding document of Zionism and the entire Zionist movement, with is clarion call for the creation of a national homeland for Europe’s Jews.

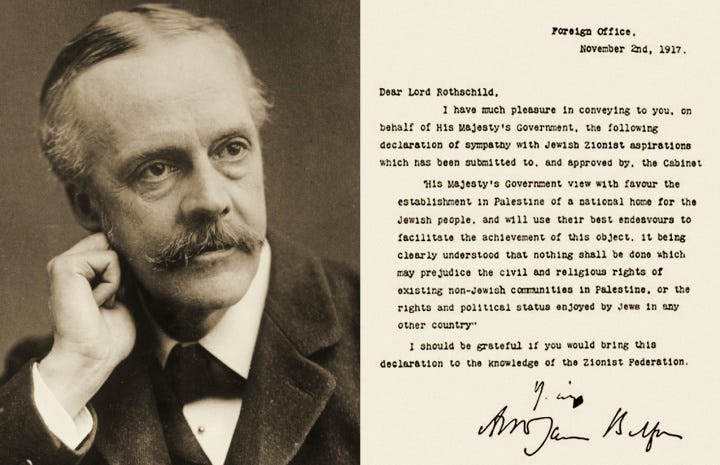

Herzl, who died in 1904, never lived to see the sequence of events that were to play out across the two world wars that dominated the first half of the ensuing Short Century, and that would in turn bring about the realization of his dream. For starters, it’s worth remembering that the Zionist cause received one of its most significant pushes forward as the First World War was nearing its climax, with the Balfour Declaration of November 1917,

wherein the British foreign secretary affirmed that “His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object.” At the time, according to historian James Gelvin, the British foreign office was motivated to issue the Declaration (notwithstanding contravening pledges the Brits appear to have been making at the same time to their Arab allies in the war against the Germans’ Ottoman confederates) in the hopes that supporting Zionist aspirations might in turn shore up support among some of their own other and more significant allies.

The British did not know quite what to make of President Woodrow Wilson and his conviction (before America’s entrance into the war) that the way to end hostilities was for both sides to accept “peace without victory.” Two of Wilson’s closest advisers, Louis Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter, were avid Zionists. And so: How better to shore up an uncertain ally than by endorsing Zionist aims? The British adopted similar thinking when it came to the Russians, who were in the midst of their revolution. Several of the most prominent revolutionaries, including Leon Trotsky, were of Jewish descent. Why not see if they could be persuaded to keep Russia in the war by appealing to their latent Jewishness and giving them another reason to continue the fight?

In the event, of course, the Declaration had little immediate effect, either on the Bolsheviks, who left the war effort nonetheless, or on Wilson, who declined to include a Jewish state as part of the postwar Versailles settlement

that enshrined so many other national aspirations, while at the same time shredding the losing German side’s prospects so savagely that many even at the time argued that a second war would now likely prove just about inevitable.

Few even then though could have predicted just how unprecedentedly horrendous the resultant Nazi German regime would prove, or how calamitous for Europe’s Jews. And there is little doubt that following the Second World War (braid into braid, strand upon strand), the case had become well nigh irrefutable that the surviving Jewish remnant indeed finally did deserve a state of its own. But—and here is the crux of the matter, at least in terms of how history thereafter would play out—why not the state of Bavaria, for example, or the Ruhr Valley, or Vienna and its surrounds? All sorts of massive movements and relocations of population were taking place in the years immediately after the war. Wouldn’t a more just settlement of Jewish claims have taken territory from those who had inflicted the most horrific suffering and violence upon them, and who would as a result have had the least justifiable cause for complaint?

The fact of the matter is that Europe—all of Europe—had no appetite for such an outcome. Even after the Holocaust, anti-Semitism was still rampant in the higher counsels of governance across the continent (as it had been, for that matter, throughout the war in the relevant reaches of FDR’s State Department).

Far easier to foist the problem onto the Arabs of Palestine. This despite the fact that Palestine had been only one of many possible sites for such a homeland in the early days of Zionism (for many years Uganda, for example, had been given almost equal consideration, and secular Zionism hardly based its claims on any biblical standing), and likewise despite the fact that, all that “A land without people for a people without a land” rhetoric notwithstanding, Palestine was already full up with people who had been residing there quite peaceably for centuries (even the Balfour Declaration had acknowledged, in a proviso that has tended to fall out of people’s memories, how it should be “clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”).

The point I am trying to make here is that the settlement forced upon the local Arabs of Palestine in the years following the end of the Second World War was in many ways every bit as blatantly unjust and corrosive as that forced upon the Germans at the end of the First World War. (When Palestinians decry it as the last colonialist land grab, undertaken at a time when colonialism was in fast retreat everywhere else, they have a point—a point albeit aimed at Europe generally even more than at the Jews, though Jews supplanting indigenous olive groves with Northern European pine forests so as to cover up evidence of their own depredations hardly get off scot-free.) And, more to the point, every bit as fraught with ongoing consequence.

It is in that sense that the so-called Short 20th Century has yet to play itself out. And this is more than a mere quibble over historiographical taxonomy. Because there was one other braiding strand rising up and out from that history that needs to be considered and layered back in: the way in which predominantly Germanic physicists (a plurality of them Jewish) were cracking the atomic code across those very years of the first half of the Short 20th Century, thereby giving rise to the creation (in exile) of an atom bomb

that ended the Second World War and then defined the Cold War that followed, right through 1989, though one whose awful pall persists to this day, in arguably its most fearsome prospect, in the form of the Israeli arsenal. (Okay, granted, either the Indian/Pakistani stashes or the much, much smaller North Korean one may come in a close second, but those belong to other narratives.)

I say this because of the recurrently rabid (see my first article in this triptych) temper of so much of what passes for Israeli policy these days with regard to the Palestinians, and the seeming inability of so many Israelis (and their allied apologists abroad) to credit the sheer ongoing human suffering that those policies bring about or to be able with any accuracy to weigh that suffering in proportion to their own discomforts (see the discussion of brain damage in my second piece). And I’m not saying that those two tendencies would necessarily, by themselves, escalate matters to the level of a potential nuclear strike. Rather it is the way the combination of the two, stretched endlessly into the future, with no countervailing pressures of the sort that perhaps only American leaders might be able to bring to bear (but never, never, never seem like they ever will, hogtied and hobbled as they in turn are by the various domestic Likkudist neocon and Christian evangelical lobbies)—how those two together may well serve to isolate the Israeli state more and more, such that it wedges itself into an ever more self-righteous and self-pitying corner (its military leadership increasingly drawn from the most self-righteous and self-pitying sectors among the settler activists, its civilian leadership driven to ever more extreme positions by the ever more desperate reactions their policies may in turn provoke among the Palestinians), and then, down the line (especially should things turn grim), who knows what a sufficiently panicked Israeli elite might do, given the availability at hand of those “seventy-five to four hundred nuclear weapons” one keeps hearing about? Seymour Hersh’s so-called Samson Option? (The option, incidentally, the Christian evangelicals are banking on, theirs being a millennial timescape far vaster than any piddling Long or Short Centuries.) Masada?

The point, finally, in this context, is that the perhaps not-so-Short 20th Century, which began exactly a hundred years ago this weekend, won’t truly have wound itself out till the Israeli-Palestinian impasse is resolved, one way or the other.

Let us pray.

* * *

CODA TO THE FOREGOING

Interesting in this context, how by the end of his life, in 1974, Auden himself was perhaps reconsidering the core of his dark ruminations of 1939, or so might be suggested by a coda he appended to “Archeology,” one of his very last poems and one of my own favorites (for the entirety of which, see here.)

Coda

From Archaeology

one moral, at least, may be drawn

to wit, that allour school text-books lie.

What they call History

is nothing to vaunt of,being made, as it is,

by the criminal in us:

goodness is timeless.

And so may we yet hope, how someday goodness may yet win out and rescue us all from the only seemingly endless cycle of grievance and revenge. This at any rate was the surmise of Seamus Heaney in his The Cure at Troy, his rendition of Sophocles’ Philoctetes, published in 1991, in direct response, one fancies, to the marvels, all around the world, of those immediately preceding years:

Human beings suffer,

They torture one another,

They get hurt and get hard.

[…]History says, don’t hope

On this side of the grave

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that further shore

Is reachable from here.

Believe in miracle

And cures and healing wells.Call miracle self-healing:

The utter, self-revealing

Double-take of feeling.

If there’s fire on the mountain

Or lightning and storm

And a god speaks from the skyThat means someone is hearing

The outcry and the birth-cry

Of new life at its term.

It means once in a lifetime

That justice can rise up

And hope and history rhyme.

For which is it going to be? I keep thrumming, wondering, back and forth, braiding, layering. Those two vantages of Auden’s, the Heaney, and the final lines of evaluation at the conclusion of Margaret MacMillan’s magisterial account of the years leading up to the outbreak of the First World War, The War That Ended Peace (her own contribution to the floodtide of retrospective considerations that marked the centennial year of 2014):

If we want to point fingers from the twenty-first century, we can accuse those who took Europe into war of two things. First, a failure of imagination in not seeing how destructive such a conflict would be, and second, their lack of courage to stand up to those who said there was no choice left but to go to war. There are always choices.

Or, to phrase the same idea just slightly differently (returning to a slightly later moment in that same 1939 poem of Auden’s):

We must love one another or die.

* * *

INDEX SPLENDORUM

***

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Hmm. We’re still pondering: let’s see how the world goes…

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

* * *

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

24 hrs ago

Such a beautiful installment: this captures much of what I have wanted to express about the current crisis in Palestine/Israel—and much I didn’t even know that I wanted to express. For me, reading, like writing, is not so much the discovery of what one already knows, but the discovery of what one doesn’t know that one knows. A work of wonder. Thank you.

I understand the compulsion to write about the terrible situation in Israel and the Gaza Strip (and northern Israel, near Lebanon). But I regret to read what I found in your latest “cabinet.”

____________________

First, one can readily acknowledge that Israelis have made numerous errors in humane responses,, over the course of the past 75-plus years. And no fair-minded person could absolve PM Netanyahu for all that he has done (somewhat Trump-like) to make things worse. The beleaguered people of Israel have carried out numerous excesses at various times throughout their history.

(I, personally, would find it hard to judge such people, who live with frequent, sporadic sirens announcing incoming rockets and maintain their own “safe rooms,” and must individually decide when to place themselves in them, as each alert is heard.)

____________________

But I can think of only one reason for placing the burden for the welfare of the Palestinian people on the shoulders of the frequently attacked, and invaded, citizens of Israel. How and why can the whole of this, from 1948 forward, be something for Israelis to resolve—on behalf of the miserable and seemingly feckless Palestinians?

The best and strongest international forces for peace in the area ought, most-naturally, to fall to the Arab neighbors, surrounding. Egypt could have built the Gaza Strip into a powerful force for independence—the “two state solution.” Yet, they have not.

Queen Noor, the Palestinian-American queen of Jordan, was heard this past week, explaining why Palestinians are not welcome in her country.

This weekend, I heard of an experiment undertaken by one of the farther-removed countries in the region. Was it Qatar? Iraq? Kuwait? I don’t recall.

The result of that generous experiment was reportedly that the Palestinian groups (in whichever country, which I unfortunately forget) set up their own, individual state-like parts in the larger country. Violence and dissension was the result. The refugees, numbering a number of some-hundred thousand in all, were ultimately expelled.

____________________

The cause of all this Middle Eastern strife, at this point, is two things.

One is the unwavering determination, of some of the area’s Islamist groups, to create a single Caliphate in the whole of the region. (Such a caliphate is to include all of the area’s Muslim nations. Thus, no area or sovereign nation there is safe.)

Thus, the enemy of the entire region is not Israel nor the Palestinians. The enemy is the Islamist-terrorist state.

How anyone can believe that this situation is one that Israel, alone, can solve, can be attributed to the second of the two motivations that drive the violent discord between Israel and any of its neighbors.

The Second Thing:

There’s a word for that belief. I would rather not name the world-wide bigotry, but you surely know that term.

PS: RIP the fine genius of an artist: Bob Irwin