October 13, 2022 : Issue #27

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

For starters, a pair of aesthetic-political considerations of matters Russo-Ukrainian, followed by an extended meditation on a remarkable recent body of work by the New Mexico photographer Kate Joyce with her revelatorily embodied vantages from the window seat…

***

FOR STARTERS

Two Responses to the Russo-Ukrainian Imaginary

One: Those Tanks

As may be recalled, there was a certain amount of confusion when, at the outset of their “special military operation” late last February, the Russians started spray-painting the stark letter Z all over the tanks and armored personnel carriers they began pouring into neighboring Ukraine.

The scary slashing insignia, without any further elaboration, even began appearing on billboards all across the Russian motherland, and presently, as slathered graffiti all over Europe (from Belgrade to Glasgow).

Europeans and Americans, for their part, could be forgiven for catching a whiff of finality in the aggressive implications of the letter in question, a sense of “once and for all,” a whisper of the final solution (to wit, Zyklon B) in this, the very last letter in the alphabet.

The trouble was there is no Z in either the Russian or the Ukrainian Cyrillic alphabet, and the closest approximation, which is written out “3” (albeit pronounced “ze”) is actually merely the seventh letter in each of the alphabets in question. (I was momentarily reminded of the way the instigators of Polish martial law, back in December 1981, were so taken aback when opponents began flashing the Churchillian V sign in opposition. “There is no such letter in the Polish alphabet,” General Wojciech Jaruzelski, the instigator of the Polish State of War, bewailed, with some justification, the Polish word for victory, for example, being spelt “wiktoria.”)

Russian propagandists began spewing forth a veritable octopoid cloud of possible justifications for the symbol, suggesting it stood in for the Russian word for “West” (Russian: запад, romanized: zapad) or "for victory" (Russian: за победу, romanized: za pobedu) or “completion” as in "The task will be completed" (Russian: задача будет выполнена, romanized: zadacha budet vypolnena).

Or not. As the completion of the task in question began to appear ever more problematic, Americans and Brits began suspecting that maybe the Z simply stood in for Zilch or Zero.

Ukrainians for their part were probably closer to the mark in their suspicion that the insignia reeked of Zieg (as in “Sieg Heil!”) or Zswastika, and the Z did indeed have a certain morphological resemblance to the Nazi swastika symbol, especially ironic in that the Russians had at the outset claimed the decimation of “Ukrainian neoNazis” as one of their principal war aims, or rather, ahem, “Special Military Operation” aims. (Again, a projection not so foreign to we Americans as when our own neo-fascists, such as Rush Limbaugh, took to denouncing “femiNazis,” or when would-be election-stealers took to demanding that the other side be made to “Stop the Steal.”)

At any rate, I was discussing all of this the other day with my Houston-based Ukrainian-American artist friend Nestor Topchy, who’d recently called on fellow artists to come up with ways to paint Ukrainian tanks, headed for battle, with exuberantly creative camouflages. (For his own part, Topchy looks forward to the day when he will be able to paint over ultimately-victorious Ukrainian tanks in the mode of a traditional tenth-century pysansky egg illuminator, and has been seeking like-minded conspirators.)

One thing led to another, and before we knew it, we had a maybe even better idea.

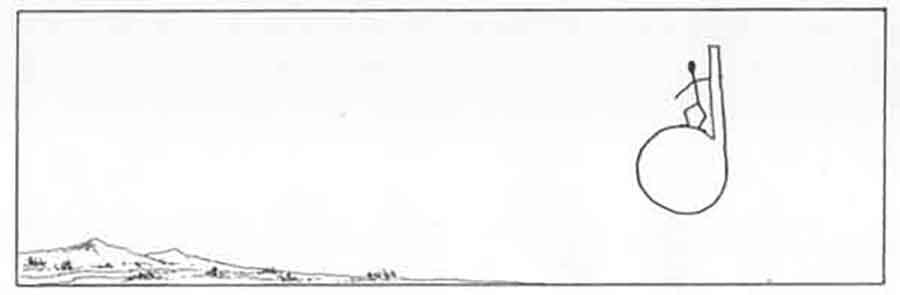

How about, in Nestor’s rendition,

After all, “A” is in fact the first letter in both the Russian and Ukrainian alphabets as well as our own, and furthermore reads the same way either coming full bore at you or in your rear-view mirror, if you happen to be retreating in full-panicked flight. It has a nice top-dog Alpha whiff to it, and suggests—as opposed to the Russian “Z”—a sense of “first things first.”

And finally, for my own part, it puts me in mind of Hannah Arendt, one of the preeminent political philosophers of the immediate-post-war period, who in her great treatise on The Human Condition (1958) suggested how the human capacity for founding things may constitute humanity’s single greatest beneficence:

It is in the nature of beginning that something new is started which cannot be expected from whatever may have happened before. This character of startling unexpectedness is inherent in all beginnings and in all origins… The new always happens against the overwhelming odds of statistical laws and their probability, which for all practical, everyday purposes amounts to certainty; the new therefore always appears in the guise of a miracle. The fact that man is capable of action means that the unexpected can be expected from him, that he is able to perform what is infinitely improbable.

A passage that seems to ring absolutely true with regard to what seems to be happening in Ukraine today, under the withering assault from the Russian Z.

NOTE: Topchy has in the meantime been elaborating his pysansky tank blueprints (for the lastest version, see here, and note how he has now incorporated the “A” idea into his Easter egg approximations). And for those looking for a less fanciful and more immediate way to contribute to humanitarian relief efforts within Ukraine, especially with the winter coming on, here is a Polish NGO that seems to be have been doing very good work, transparently and efficiently, purchasing requested items (food, tourniquets, winter clothing, etc, in Poland and transporting them directly to their Ukrainian counterparts), and one can donate to them directly in dollars.

*

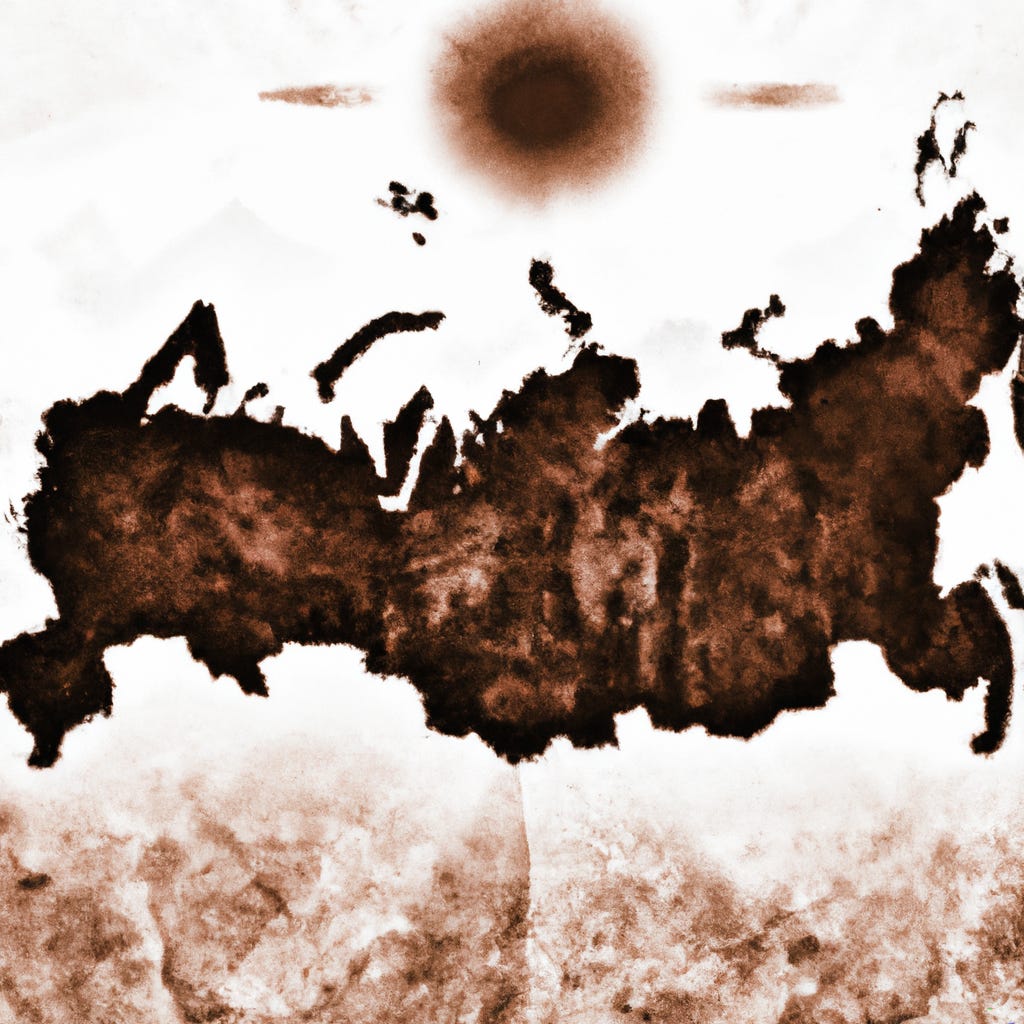

Two: That Cloud

My friend the polymathic filmmaker Gil Kofman, for his own part, has been playing with one of those new-fangled AI image-generating programs that seem to be cropping up all over the place, noodling around (in his own case) with themes Russo-Ukrainian, and came up with the startling creation above, among several others frankly less compelling (or so it seemed to me).

He initially accompanied the images with this note: “Used AI program to create these images of what’s happening in Russia now.”

To which I wrote back: “Tell me more of what you mean about working with AI program to create that Russia Rorschach image: Were you going for vampire bat or inkblot or what? (And is any or all of that me projecting or you intending or the machine contriving?) What did you prompt and what did the program do?”

To which he replied: “The program is called Dall-e and you just write your prompt and it delivers images. I said I wanted a map of Russia with an incandescent nuclear sun. Later I got rid of the map and added a marsh and incandescent roses in the style of Anselm Kiefer (I mentioned that name) and it gave me those images.”

All of which raises all sorts of issues. For one thing, what is an atomic mushroom cloud itself, qua image, other than a perfect roiling symmetrical Rorschach field, veritably calling out for projection? (For that matter, the same might be said of most any Anselm Kiefer images.)

In this context, too, consider the 1947 monument built over the ruins of the Majdanek concentration camp outside Lublin, Poland:

That brute monument somehow managed to meld the horror of both the atomic mushroom and the nazi crematoria clouds into one overarching, looming petrified specter. (I wish I could convey to you the disconcerting eeriness of being there on a damp foggy morning, the slipperiness of the smooth inclined slope down which one proceeded—decades before Maya Lin’s deployment of a similar effect in her Vietnam Memorial—approaching that overbearing stone bellows, and the jagged sharpness of the rocks jutting out from either side.)

For that matter, Kofman-Dall-E’s image also seemed to have a whiff of the Shroud of Turin staining its associations. (Talk about a Rorschachlike images avant la letter!)

Skeins of free associations like these intrude upon most any fresh image (viz., my entire taxonomy of such convergent effects back in issues 11 through 15).

More generally, though, in this particular instance (as in so many others like it that have recently been cropping up all over), I find myself wondering what exactly is happening when humans and bots start projecting off each other? What roiling prospects (a veritable mushroom cloud, in and of themselves) seem suddenly to be pouring forth?

* * *

The Main Event

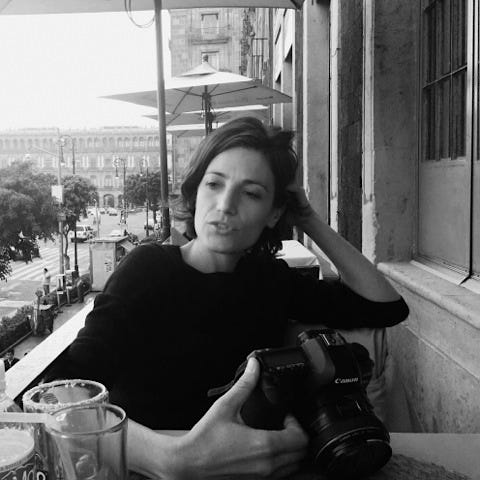

KATE JOYCE’S EMBODIED VANTAGES

(The following appreciation is appearing this week as the afterword to Kate Joyce’s Metaphysics, out from Hat and Beard.)

Kate reminds me about Ursula LeGuin’s poem, “GPS,” how for Le Guin

There are two directions, out and back

from the still center of the compass rose.

There are two places: home, away. I lack

a map that shows me anywhere but those.

But then of course there is also the in-between, the from-one-to-the-other, which nowadays, when one is speaking of any sort of distance, as often as not gets traversed in flight.

For some people, the experience of flying from one place to another can be one continuously nerve-addling jangle, from packing through baggage claim.

Others, and I am one, drift into an alpha-wave stupor—time slows to a crawl and experience to a null point. The entire excursion transpires in a state of suspension, a sort of attentional hibernation.

And then there’s Kate, for whom the experience of air transit clearly quickens a heightened attentiveness: lucky her.

Lucky us.

*

Time was that transit stretched out at the stately pace of foot, or maybe hoof, at most wind. Velocity was hardly an issue: things took as long as they took. But then in the late 1830s, as trains hove onto and across the scene, velocity came to be of the essence. In his latest book, Geoff Dyer has been rhapsodizing, regarding JMW Turner’s iconic painting “Rain, Steam, Speed —the Great Western Railway” (1844),

how “According to one account, a passenger on a Great Western Train saw a man she later realized was Turner leap up from his seat and crane his neck out the window to feel the tumultuous sense of speed.” Whether or not that report is reliable, Dyer suggests,

it vividly demonstrates the purpose of the painting: to convey not an impression, but a sensation—of speed. Although we are seeing the train from outside—as if we are watching it hurtle by—we share the experience of the people within it. If the painting has a documentary value, it is in registering a change in the nature of perception—how our perception of time and space is being changed by speed.

“The annihilation of time and space” being how people came to think of the near simultaneous onslaught of trains and telegraph and chemical photography, one hard upon the next, across those very years. (And subsequently: how one of the first things that the Lumiere Brothers committed to motion picture film, in 1895, was a similarly disconcerting sequence of a train surging head-on into a station.)

Somewhere I read (I’m not sure where, perhaps in Wolfgang Schivelbush’s quintessential The Railway Journey, or else in Rebecca Solnit’s equally essential rhapsody on the life and chimes of Eadweard Muybridge, “in the Technological Wild West,” River of Shadows) how in the early days of train travel, so extreme was the relative acceleration in velocity compared to earlier modes of transport, that contemporary letter writers reported how powerfully they experienced the sheer force of the speed as their bodies got hurled back against the backrests, the muscles of their face stretched taut against their cheekbones, as the trains reached speeds, good lord, of 40 or 50 miles an hour!

Then again, time was, time was true. But trains (or more accurately transcontinental train travel) put a stop to all that. In olden times, in every village noon occurred at the precise moment the sun reached its solstice zenith over the village spire. But that in turn meant that clocks in towns a few dozen miles to the east or west of each other might be set several minutes apart; which in turn didn’t matter till the instigation of transcontinental train travel, when a train stopping at seventeen places between New York and Chicago, say, therefore needed to carry seventeen different timepieces on board, just to stay on schedule. Hence the need for time zones, which came into being in 1884 at an international conference in Washington DC, along with the designation of Greenwich as Longitude degree 0 and its Mean Time as the universal standard.

Is it any wonder that a genius, born in 1879 and growing up in a world grappling with issues of simultaneity and the like (“But when it is noon in Paris, what time is it in Ulm?”) might go on a few dozen years later, in 1905, to postulate an entire Theory of Relativity in which trains themselves (as in “lightning striking our rail embankment at two places A and B far distant from each other”) would prove the principal props in his thought experiments, and the very mass of matter would get formulated in terms of that ultimate velocity (the speed, of all things, of light)?

The years 1903-5, as it happens, also saw the culmination of the efforts of the Wright Brothers at Kitty Hawk to achieve the world’s first machine-powered aerial flight—with the sensation of velocity, the sheer rattle and the noise of it, again being of the essence, from biplanes through propeller-driven mail couriers and fighter-bombers and civilian passenger aircraft.

But with the coming of jet flight, as Roland Barthes noted in one of his monthly occasional Mythologies essays in the early fifties, there came a crucial change: “What is immediately striking in the jet man [the titular subject of his essay, as opposed to the earlier prop plane pilot] is the elimination of speed... for excessive speed turns into repose. The jet man {and presently his passengers as well} are defined by a coenesthesia of motionlessness (at 2000 km/hr in level flight, no impression of speed whatsoever)”: a smooth near-silent humm, with stillness at its core.

*

So, I ask Kate, what’s your backstory anyway?

And says she: “Well, I grew up in a house of artists, in an extended family of artists, in a town of artists.

“When I was a child my family often took car trips around the American Southwest, with two regular migrations in the winter: one to visit the Bosque del Apache, a bird sanctuary in southern New Mexico where we viewed and were amongst herons, egrets, snow geese and more—and the other trip, my dad would take my sister and me to Yuma, Arizona, for the Yuma Art Symposium.

“In 1991 photographer John Gossage presented at the Yuma Symposium. Between something I saw in Gossage's work and the influence of my aunt Julie Dean, who was a photographer and someone I was close to, I came back wanting to pursue the medium somehow. I was around 11 or12 years old. For my 13th birthday I was allowed to set up a darkroom in the attic (that was in 1993).”

In passing, she mentions how she went on to study at San Francisco State and later the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke. “I kept my darkroom until sometime around 2011/2012, coincidentally around the same time that I started photographing in airplanes and traveling regularly. I was living in Chicago at the time. I was doing freelance architectural photography for firms around the Midwest and East Coast. I was beginning to work on art- documentary projects in Durham, North Carolina, and Knoxville, Tennessee. I had a gallery in New York. I was teaching in Mexico and Peru. My family was still in New Mexico, California, Tucson, Colorado, Maine. Friends were scattered around the United States, Europe and even in Brazil. These are some of the reasons I was flying so much—surely over fifty flights across the next several years. Inhabiting the strange limbo of airports and the loneliness of planes, I found the window seat to be its own destination and something like a studio of constraints. Initially I’d focus on the view out the window, the land and cloud and horizonscapes down below, but increasingly my attention was being drawn to the constantly changing play of light across the nearer-by wings and engines. I was recently looking through some of my contact sheets from 1995, and I found this one:

'“Which reminds me of that great Barry Lopez line from his essay ‘Flight,’ to the effect that of a plane’s six million individual parts, three million are rivets. Among those 1995 contact sheets, I found this trill of images as well:

which in retrospect reads like a row of passengers one behind the next. Whereas before I’d loved looking at the effects of sun on wing, suddenly I discovered the more intimate vantages within the aircraft—bodies, hands, drapery.” Kate paraphrases a much-beloved passage from Olga Tokarczuk’s recent narrative collage Flights, the direct quote from which she subsequently mails me (“He sat squeezed into his chair amidst two hundred people, in the oblong space of the plane, breathing the same air they were breathing. In fact this was why he liked travelling so much - en route people are forced to be together, physically, close to one another, as though the aim of travel were another traveller.”) “So there’s all of that,” she continued, “but also the way outside light gets reflected inside, with each body inside the plane’s cabin becoming its own sun. Especially so after an epiphany I refer to as ‘SFO to ORD, May 5, 2012,’ which blazed into being, as I happened to be training my camera on the far side of the cabin:

That vivid red blush on the far side of the plane as the woman over there moved around in her seat: out of the monotone monochrome, that sudden moment of color.”

Sort of like Bergotte’s vision in Proust, I suggest, as, standing before Vermeer’s View of Delft on loan somewhere there in Paris, Proust’s writer stand-in suddenly notices “that little patch of yellow wall, with a sloping roof, that little patch,”

which veritably slays him. (“Meanwhile, he was not unconscious of the gravity of his condition. In a celestial pair of scales there appeared to him, weighing down one of the pans, his own life, while the other contained the little patch of wall so beautifully painted in yellow. He felt that he had rashly sacrificed the former for the latter. ‘All the same,’ he said to himself, ‘I shouldn’t like to be the headline news of this exhibition for the evening papers.’”) Which, alas, he was destined to be, for no sooner had he had that thought than he proceeded to slump down onto the circular settee and then the floor, victim of a heart attack: “He was dead.”

“Hmmm,” Kate responds to my association. “I’m working my way through Proust right now for the first time in my life, and it’s extraordinary, but I haven’t reached that passage yet.” It’s in The Captive. “Which happens to be the volume I’m just starting, though I’m using the Carol Clark translation which deploys the title The Prisoner. But it’s funny, too, because over the years I’ve sometimes come to think of the organization of life within a plane’s fuselage as sarcophagal—”

How so? “Well, that association may wend back to 2001, when, the night of September 10th, I had boarded a red-eye flight from San Francisco to Newark. This was my first visit to New York and I arrived that next morning half an hour before the first plane struck the World Trade Center. Back at the airport, with a full tank of fuel and cabin full of new passengers and staff, the aircraft we had just been on became United Airlines flight 93, the fourth highjacked plane that was eventually flown into the ground over Pennsylvania. Which as you can imagine....” Her voice trails off, before resuming: “But other times, that fuselage can get to feeling more like a chrysalis than any sort of funerary structure, a stasis from which the passengers will emerge subtly transformed on the far side. And in that confinement that feels close to both birth and death, there is such incredible light.”

*

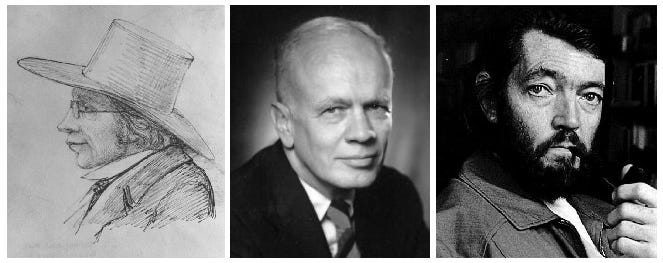

Before becoming a novelist, and indeed one of our finest, Walker Percy had been trying to become a medical doctor, perhaps a pathologist; only, in 1942 he contracted TB from a body upon which he’d been performing an autopsy, and came close to dying. Across the several ensuing years of his fitful recovery he literally became a puzzle to himself (after all, in a sense he’d become the disease he had been studying) and that happenstance crisis sent him hurtling right out of medicine and into philosophy, specifically into phenomenology and existentialism and the precursor to them both, Kierkegaard. Percy’s passionate pursuit: an analysis, as it were, of the alienation that he came to feel had saturated the modern condition—the sense of being alienated from the vividness of being, lost instead in the deep boredom of the everyday mundane. (“One tires of living in the country and moves to the city,” Kierkegaard had written almost exactly a century earlier, in his guise as the aesthete A, author of the first volume of Either/Or, in an essay on “The Rotation Method”: One tires of one’s native land and travels abroad; one is europamüde and goes to America, and so on; finally, one indulges in a sentimental hope of endless journeyings from star to star.” But none of it works, there is no reprieve from deep boredom, because in a certain sense one is oneself deeply boring—one needs being shaken out of oneself, or rather to find not so much a new place to be as a new way of being.)

In 1956, five years before releasing his first novel The Moviegoer, Percy published an essay, “The Man on the Train,” in the Partisan Review, about a daily commuter who has been taking the same 8:15 local on the New Haven line from his suburban home to his downtown job, the same train, the same job, past the same anonymized neighborhoods, back and forth, for years and years on end—and Percy spends some time anatomizing The Man’s profound alienation. But then, surmises Percy, what if one day the train simply broke down and ground to a stop, and while the train workers took to trying to repair the bollixed engine, our man just exited the train and took to walking about, actually visiting “the yellow [!] cottage with a certain lobular stain on the wall [!]” that our Man had previously spent years racing past, oblivious, without thinking about or even really seeing any of it at all. And what if the person on the porch of that house suddenly called out to him and engaged him in conversation. An exchange which would presently shake our Man clear out of his profound alienation and to his very core.

But the thing I had forgotten, or never really caught in the first place, and only just realized this very moment, having gone down to my bookcase to refamiliarize myself with the Percy text, is that the place the train breaks down in the story is “somewhere between New Rochelle and Mount Vernon,” which is to say in Pelham, the only township between the two, which is the very town I myself have been living in for the past thirty-five years, in a modest house right by the train tracks, the very same house, I now find myself fancying, as the one imagined into being in Percy’s example, and where I am writing these very words! (Talk about a frisson: In an uncanny inversion, I can almost sense the fellow ambling down from the embankment just across the way at this very moment and getting set to call out to me, to pull me out of my own quotidian alienation.)

I mention all this to Kate and she meets my Proust-Percy references and raises me a Julio Cortazar. “Have you ever read his short story, ‘The Continuity of Parks’? It’s in the same collection as ‘Blow-up,’ which as you can imagine is a story of considerable import to photographers like me. But in the Parks story, which is very short and for that matter I am sure you can find it online, there’s a moment quite like your sense of that Man on the Train climbing out of Percy’s essay and arriving on your very porch. Only it’s somewhat more distressingly fraught.” And indeed it is: talk about sarcophagal associations! But, I hazard, it sounds like Cortazar’s short tale may share various other phenomenological implications as well with the Percy, specifically to the experience of intersubjectivity (the way in which we ourselves only really come into the world as subjects by way of the existence of others). “Indeed,” Kate concurs, “Because that Cortazar story also relates to something I’ve always felt about these airplane photographs of mine, that sense that the arm I am looking at in front of or behind me, could be seen the same way by that very same person sitting in front of or behind me, were they to train their gaze in my direction. Reduced to limb, drapery, skin, and light, we resemble each other, we are repetitions of each other, we are each other’s other.”

But anyway the point I was trying to make before I was so delightfully interrupted is that our Kate on the Plane, if you’ll allow, is actually in all sorts of ways the very opposite of Percy’s Man on the Train. For one thing, it’s not as though she could ever just walk out of the stalled plane in order to re-engage with the world. On the contrary, over the past decade or so, she has been rushing to board every single plane, precisely so as to seize the window seat from which to re-engage the vividness of lived experience, “all the while,” as she wrote on one of the wall panels at the inaugural exhibit of these photographs at SITE Santa Fe, “finding stability and some kind of constancy amid these myriad various jobs and experiences, in that small space on the airplane between the window and seat.”

Who’d have thunk it? Can anything seem more ultimately boring, more alienating, than the small sliver of space between the window and the seat in yet another commercial jetliner? And yet, as Flaubert famously said, “Anything looked at long enough becomes interesting.” Interesting in that sense becoming a gerundial verb, connoting the active, outward projection of interest: It’s not so much that the world does or doesn’t interest you: rather you yourself interest (you bestow interest upon) the world. Flaubert’s, I suppose, being another way of saying, of urging, “Look at what bores you!” Look at what you have allowed yourself to grow blind to, to have become alienated from. And if you see something (certainly if you are an artist), say something, since as Eudora Welty often insisted, “Making the real real is art’s responsibility.”

Say or show or prize: since, if you are a photographer, you prize it. In both senses: you value it and you seize it. And you do so at the last possible moment, for as Cezanne once famously observed, “You have to hurry if you are going to see: everything is fast disappearing.”

*

And, on the evidence of her Metaphysics series, Kate Joyce’s is both an exceptionally layered seizing and a many-splendored gaze.

There is, for starters, the liminal. A celebration (a cerebration) of thresholds, and in several senses at that. A temporal threshold in that with several of these images it takes time for the image to emerge. Photographic images were long famous for the way they only gradually (and ever so spookily) emerged from their various chemical baths in the darkroom. With many of the images in this series (even though they were digitally prized and there was no longer any darkroom involved), it’s as if they are still emerging, fixed though they are on the wall or the page. It takes us time to make them out, or for them to make their way to us across that threshold.

But liminal, as well, in the sense of the architectural space along that inner wall, the inner skin of the plane’s fuselage. Moving one’s gaze from outside the window, the sleek aerodynamic curves of the wings and the engines, to the interior of the cabin, it takes a few moments to realize how the inner skin of the cabin partakes of the very same sorts of aerodynamic curves.

And indeed has to: Back in the day, in the early fifties, some of the designers with the first commercial jet plane producers—notably the De Havilland company with their Comet passenger planes—endeavored to reassure passengers by rendering the interiors of their cabins as terrestrially familiar as possible. The windows, for example, were straightforwardly rectangular —just like home (“Nothing to worry about here”). But then planes mysteriously started falling, catastrophically, out of the sky. It took a while to figure out why—it turned out that the pressure variants between inside and outside the fuselage cabin were so extreme that the windows began cracking and then exploding precisely at those rectangular corners. Back to the drawing board, and to those smoothed oval windows with their aerodynamically curved interior sleeves evenly distributing the various pressures along the liminal passage from outside to in.

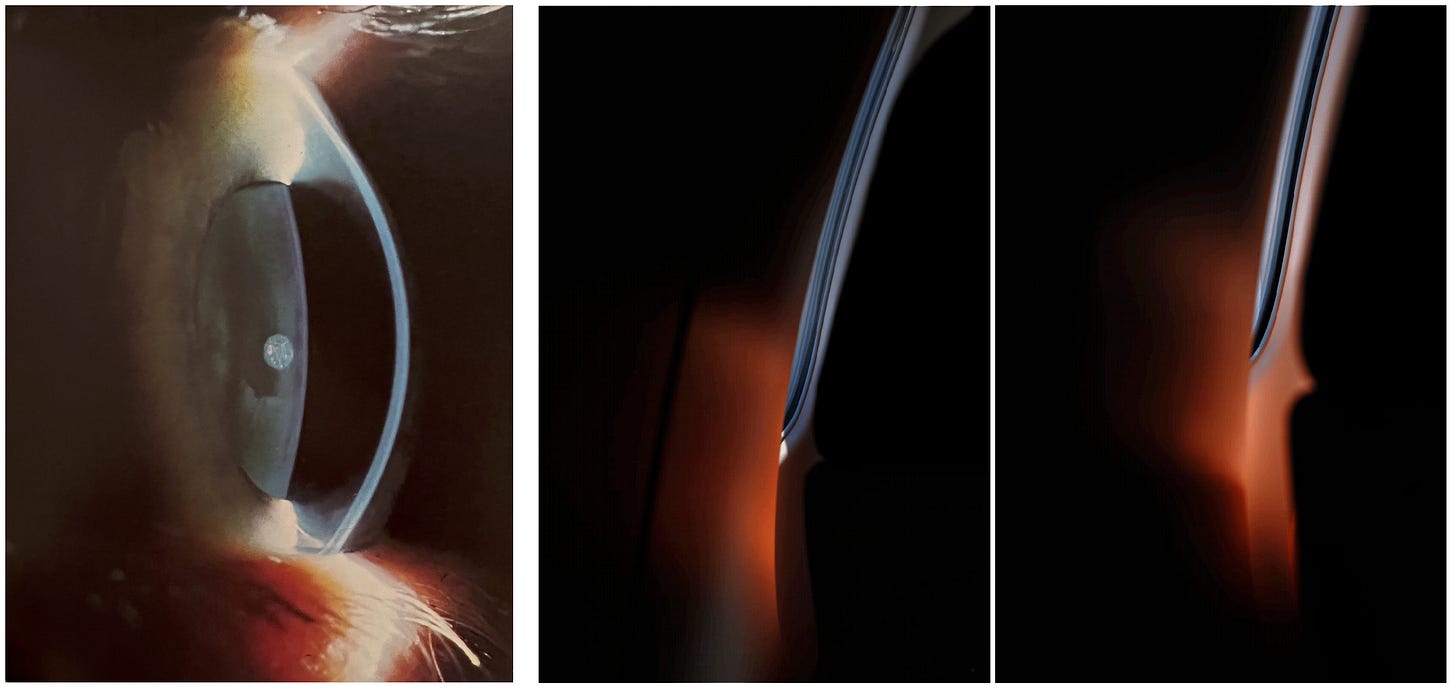

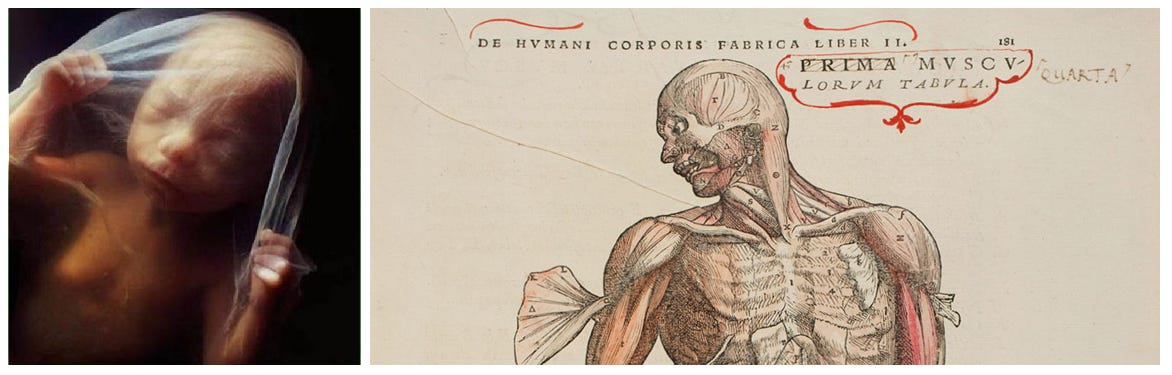

But then as well there’s the corneal (or, if you will, the optical). Kate was telling me how as a child, one of her favorite books, which absorbed her attention for hours on end, was Lennart Nilsson’s Behold Man book of photographs. And how one photo in particular held her spellbound.

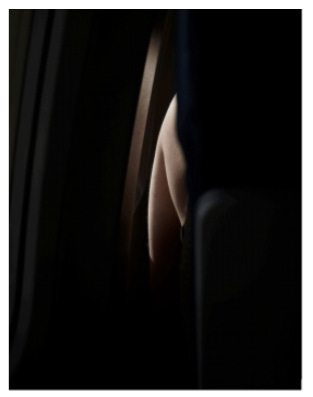

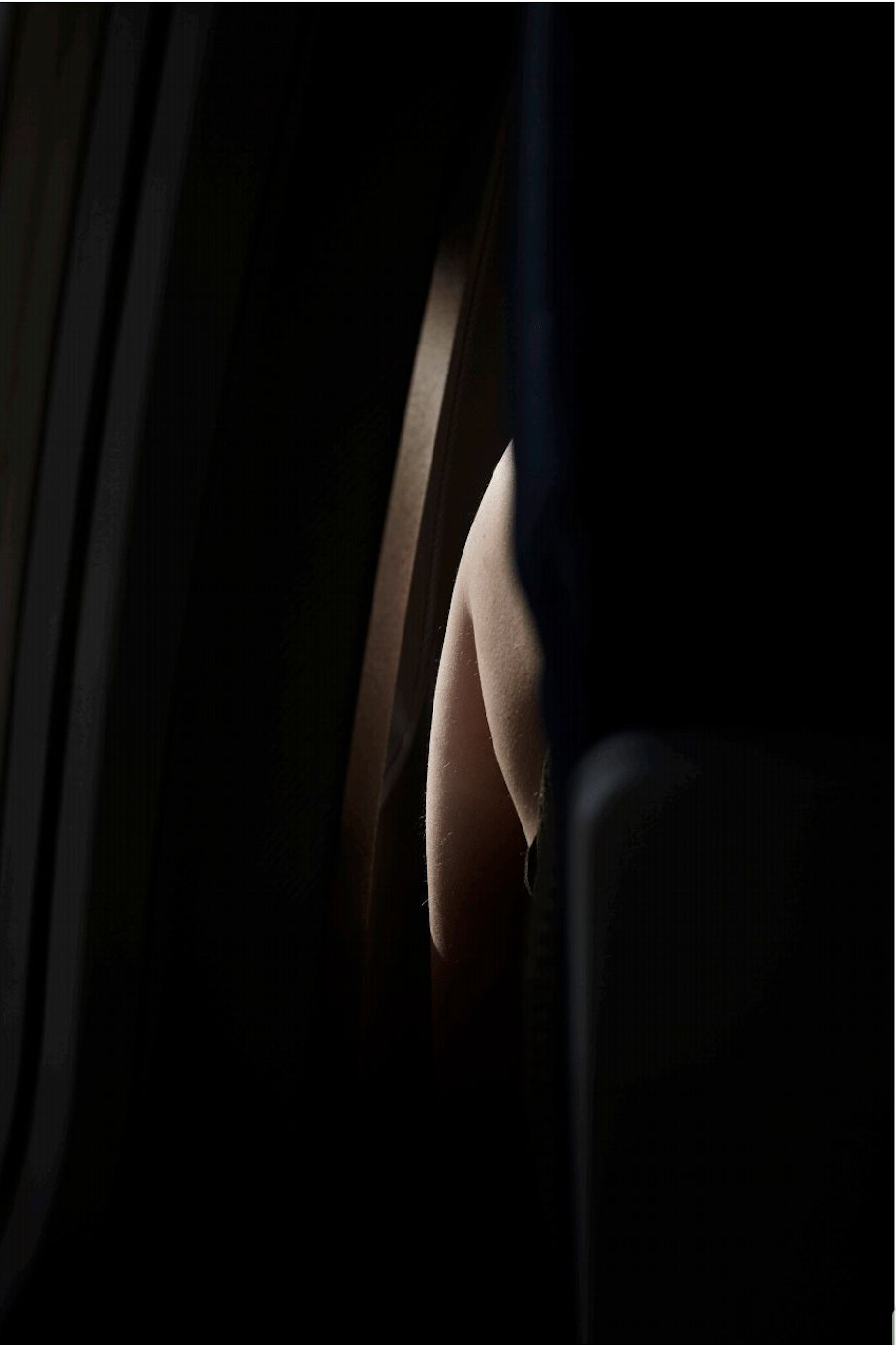

Strange how that little sliver of space between the lateral edge of the window seat in front of you and the curved inner sleeve of that seat’s window can itself come to seem like an opened (or only-just-opening) eye, alternatively staring in or out. And the way that the light pouring through, across the Barthesean stillness of that regard (the critic James Elkins has a marvelous book called The Object Stares Back) can in turn put you in mind, or did me, of other Vermeers, for example this one.

That way that Vermeer had of prizing images of women in the very act of having to stand still for some reason (because they were pouring milk or testing a balance or napping or looking at themselves assessing a necklace in the mirror) as time itself coursed on and the light poured in from the side window and across the back wall, like a tide (stillness as duration, almost a precursor of cinema). The same effect that transpires across many of these silent stills of Kate’s.

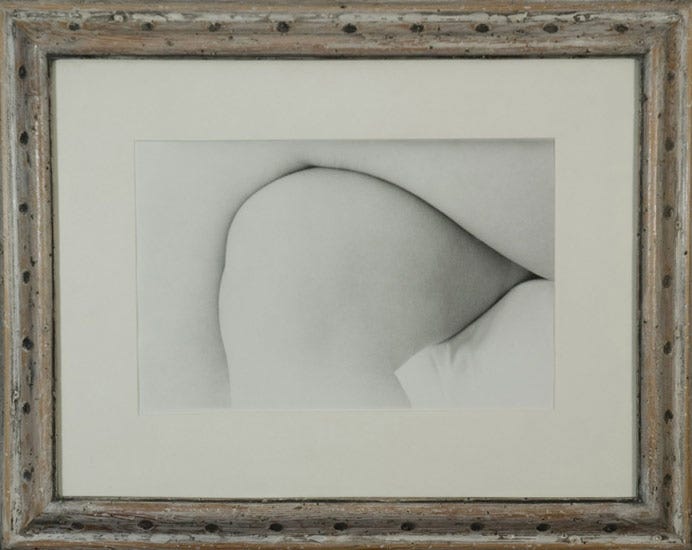

And the corporeal: light coursing not only across window sleeves but at times across bodies, or anyway body parts, sometimes some of them not immediately identifiable as such. I’m reminded of some of the photographs of Joyce’s kindred New Mexican, the late painter Frederick Hammersley, as for example in this case:

Or, for those having a hard time making out what exactly that might be, this other Hammersley from the same series, of the same subject:

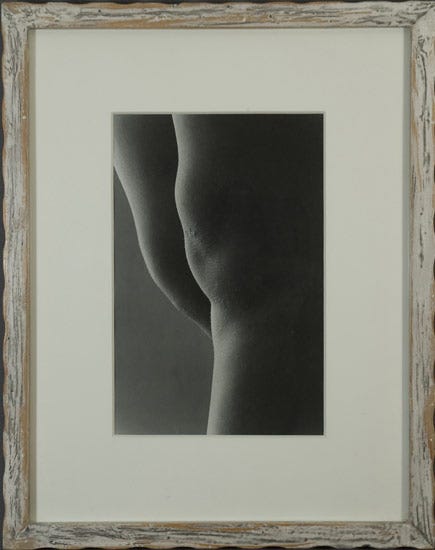

Which, of course, puts one in mind of this obverse rhyme of Kate’s:

As well as others of her images. Though not just exposed skin: sometimes, no less mysteriously, snatches of hair

(In passing, Kate quotes Beckett on Proust to me: “Curiosity is the hair of our habit tending to stand on end.”)

Or for that matter, the folds of various enigmatically embodied fabrics

which in turn remind me of how across her childhood, as Kate now again reminds me, she used to love gazing upon another set of images in that Lennart Nilsson Behold Man book of photographs, this time of fetuses wrapped in their placental folds, and of the way the great 16th century anatomist Andreas Vesalius titled his massive foundational study De Humani Corporis Fabrica: The fabric of the human body.

That association in turn provokes another, as Kate recalls a further favorite passage from Tokarczuk’s Flights novel, in which the Polish Nobelist has her planebound character Dr. Blau drift into a waking dream about the monadology of the fellow passengers ranged all about him, how

The surface of these monads hides within it vast mysteries, not even remotely hinting at the dazzling richness of these marvellously and cunningly packed structures - not even the cleverest traveller would be able to compose his luggage in this way, distancing from one another the organs, for order, safety and aesthetics, with peritoneal membranes, lining space with fat tissue, cushioning them. So went Blau's ardent ruminations through his unsound airplane half-sleep.

Ardent ruminations, indeed. Which in turn brings us to the ideational layer of Joyce’s Metaphysical project, the sense of there being there, just on the other side, beyond the sliver-shaped Looking Glass, not just other bodies but other minds, other intentionalities, just like ours, as reflected for example in the play of hands (the furthest extensions, as it were, of the thinking, gazing, musing, grasping mind—see in this context the philosopher of consciousness Colin McGinn’s thoroughly arresting monograph, Prehension: The Hand and the Emergence of Humanity):

Which in turn bring us to the final, foundational, originary layer of Joyce’s gaze across this body of work, the existential: the call to be where we are, even in as attenuated and otherwise banal a place as this, the window seat of a transcontinental jetliner.

At one point, Kate pointed me to a passage in the Sylvia Plachy’s 1990 memoir Unguided Tour, the caption the photographer, a model and idol of Kate’s, appended to the photo of a model and idol of hers, to wit:

Ten nights

before he died,

master photographer André Kertész,

my friend,

tripped and fell

while walking

back to bed

after shutting off

the hallway light.

As he was 91

and had a fever,

he didn't possess

the strength

to push himself up,

and he fell into sleep

on the floor

of his apartment.

He opened his eyes

at dawn

and thought:

“How strange

.. what lovely light

.. such interesting angles .. where am I?"

The passage immediately reminded me of a piece I myself composed a while back on the occasion of the opening of my own friend and mentor Robert Irwin’s permanent site-conditioned installation at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas:

“You wake up every morning,” the California artist Robert Irwin would often begin the talks he used to give, coming on 45 years ago now, to anyone anywhere who would have him, “and a whole world is delivered instantaneously to your senses—and you hardly give the sheer marvel of that fact a thought, it’s so taken for granted. The sights, sounds, textures, smells come flooding in, or rather maybe your awareness of, your attentiveness to the world floods out, and you just get up and go on with your day as if this were the simplest fact there could be, which of course it is not.”

Robert Irwin, that is, who used to forbid the photographing of his own works, because, he explained, conventional photography could only capture what the work was not about and never what it was, which is to say, its image and never its presence. Presence being for him an immensely loaded word, in some senses the very opposite of the immediate split-second present-tense snap of an ordinary photograph: rather attention stretched across awareness—stillness and duration, which is to say being across time. Anyway, following a long description of Irwin’s Marfa piece and its effect on me, I concluded that piece as follows:

Back home now, I wake up and find myself noticing the uncanny blush of dawn in the corner of my shade-darkened bedroom, and the rainbowlike arc of color reflected somehow off something, already decomposing, and then that sudden spear of light stabbing along the ceiling, slowly widening, and it’s all, all of it, so heartrendingly beautiful, and so very, very present: a gift.

Which is kind of how I find myself feeling about Kate Joyce’s work in this project as well, a sequence not so much of snaps as of presences. And yes, a gift many times over.

Tomas Tranströmer, the great Swedish Nobel laureate, has a wonderful poem called “Sentry Duty” where he concludes, in Robert Bly’s translation:

Task: to be where I am.

Even when I’m in this solemn and absurd role:

I am still the place where creation

does a little work on itself

Toward the end of his life, Buckminster Fuller was asked whether, having done so much to make space travel possible, he was disappointed that he himself would never make it into outer space. “But, sir,” he replied, ever so precisely, “we are in outer space.”

In conclusion, the same point phrased slightly differently: Northrop Frye used to recount (in Alberto Manguel’s retelling) how he once had “a doctor friend who, traveling on the Arctic tundra with an Inuit guide, was caught in a blizzard. In the icy cold, in the impenetrable night, feeling abandoned by the civilized world, the doctor cried out: ‘We are lost!’ Whereupon his Inuit guide looked at him thoughtfully and replied: ‘We are not lost. We are here.’”

*

NOTE: For those of you who would like to purchase Kate Joyce’s sumptuous new book of vantages from the window seat (along with my afterword), it is now available directly from the publisher, at a special 30% discount to Wondercabineteers like you, here. Note that you should simply order as if you were going to pay full price and the discount will be automatically feathered in as the last step of the checkout.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

The Animal Mitchell archive.

***

NEXT ISSUE

Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Deborah Butterfield, on the eve of a new show of her lifelong project, fashioning hauntingly lifelike horses out of collections of felled branches, which in turn get recast as exactingly patinated bronzes. And more.

Please consider helping us keep this crazycar on the road by becoming a paid subscriber. Thanks!