WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

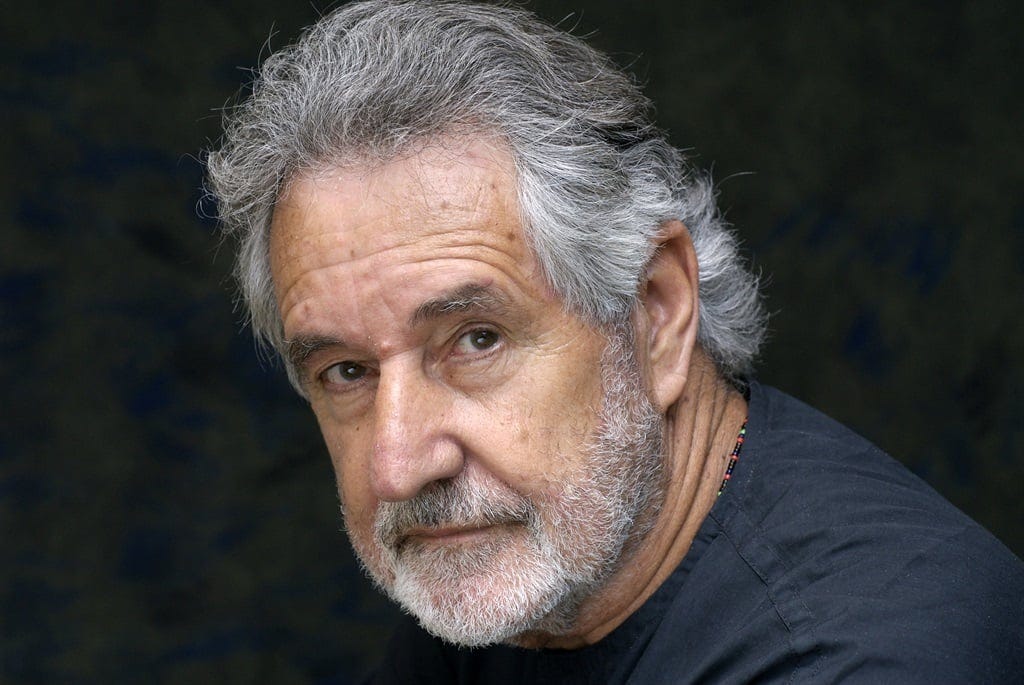

Breyten Breytenbach, a giant of Afrikaans and world culture, and a dear friend, has died in Paris at age 85.

*

The Main Event

BREYTEN BREYTENBACH, in memoriam

This past weekend, while I happened to be in London, I was stunned by the news, albeit not entirely unexpected, that Breyten Breytenbach had died in Paris, at age 85, peacefully, in his sleep, his wife of over sixty years, Yolande, by his side. Not entirely unexpected, in that he had been seriously ill for several months, though still somehow downright inconceivable. For how were we all expected to go on without his brimming, capacious, scathing, fierce, soft, gentle, kind, wise and wiseass presence? The answer, as has gradually emerged across the days since, is that somehow we will, because his was an ever-presence and it will not soon fade. I can hear him teasing me, mock-joshingly, as I write.

He was one of my dearest friends, and before that, one of my favorite subjects. My New Yorker profile of him, seven years in the making, appeared in the November 8th, 1993, issue of the magazine, and, slightly expanded a few years after that, formed the basis for the last of a triptych of nonfiction novellas that constituted my collection, Calamities of Exile.

That version begins like this:

I ONCE ASKED Breyten Breytenbach, the exiled South African poet and painter, why, in his opinion, after the fiasco of his clandestine return to his homeland in 1975 (traveling incognito as a would-be revolutionary organizer), the calamity of his arrest (his cover having likely been blown before he even entered the country, such that not only was he arrested but virtually everyone he'd contacted was arrested as well), the debacle of his trial (his appalling, groveling breakdown, his operatic recantations and expressions of contrition, all to no avail), after his being sentenced to nine years' hard time in the country's notorious penal system, why, I asked him, why had the authorities who allowed him to go on writing in prison nevertheless forbidden him to paint?

At the time, we were sitting in Breytenbach's airy, light-drenched studio, in Paris. (He had been released in 1982, a year and a half short of the completion of his nine-year term, and had immediately returned to his Paris exile.) We had been looking through a life's worth of canvases, dazzlingly colorful paintings with surreal images by turns lyrical and profoundly unsettling. He paused for a moment to think about the question, then said, "They weren't stupid. I think they must have realized that for me an empty canvas would have been an open field of freedom—and they weren't going to allow me that."

They wouldn't let him paint, and for years they barely allowed him even to see any colors. This quintessential colorist had fallen into a nightmare universe of monochrome grays and browns and goose-shit greens. ("Caca d'oie,"he had commented earlier. "That's the term the French have for the predominant color of prison life.") The pressure within him to paint—or to create images, at least—had become almost overwhelming, and finally he had managed to create and smuggle out to his wife, in Paris, a few dozen drawings. She had preserved them, and some of them were among the pictures we'd been looking at. Several seemed to derive from the tumultuous cauldron of his interior life—images of decapitation, copulation, mutilation, and confinement—but others, almost as if in compensation, seemed to be exercises in minute observation: a scuffed shoe, a folded blanket, a draped jacket, a burned note and the extinguished match. Somehow, these modest images were more affecting than the imagined ones, and perhaps the most haunting of all was a drawing entitled "The Orange, Four Times," which portrayed, first, an orange whole (its very orangeness, shining through the pencil gray, in some ways seeming to be the drawing's incantatory subtext), then the orange partly peeled, then the orange three-quarters eaten (that is, with just a few last sections to be seen), and then—well, nothing, empty air, the orange consumed).

That drawing reminded me of a painting we had been looking at earlier—one of a series that Breytenbach completed during the first years after his release. Against a lush orange-colored background Breytenbach had created what he was calling "A Family Portrait," which was in fact a group self-portrait, three images of himself at different ages all grouped together under the sign of the Bird (birds being frequent self-tropes in his poetry: birds of passage, birds of prey, lovebirds, birds unhindered in their movement, migrating birds, caged birds, jailbirds): as a poor young farm boy, a mischievous glint in his eye; as a clean-shaven, manacled prisoner in a blue jacket, putting on a brave face for the photographers at his first trial; and as he saw himself at the moment of painting, squinting through crossed eyes, prematurely aged (at least in his own mind), his black beard frosted with gray. Breyten, I found myself thinking: Breyten, Four Times.

I.

I’D FIRST MET BREYTEN Breytenbach in January 1986 in New York City at the International PEN Club's annual congress, which was taking place that year at the St. Moritz Hotel. This was barely three years after his release and a year since I myself had first encountered his writing, through the publication of his extraordinary memoir of prison and calamity, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (the middle volume, as it would prove, of a trilogy launched in 1974 with A Season in Paradise and concluded in 1993 with Return to Paradise).

Over the years, l've occasionally reminisced about those days at the PEN congress with others who were present, and time and again, Breytenbach’s name has come up, unbidden, as one of the event's most forceful presences: his mordant and self-deflating opening statement on the conference's main theme, "The Writer and the State"; a memorably sharp exchange between him and the already rightwardly-zagging Mario Vargas Llosa; his especially evocative participation in a panel on the challenge of translation. (Breytenbach, naturally, has acquired a considerable fluency in the paradoxes of translation: nowadays, he composes his poetry in Afrikaans; his prose-essays, tales, and novels, increasingly in English; his painterly base is in Holland, and his Dutch is virtually indistinguishable from a native speaker's, as is his French, as well as his Spanish—he spends increasing amounts of time in the snug little farmhouse he and his wife have managed to procure in the countryside north of Barcelona.)

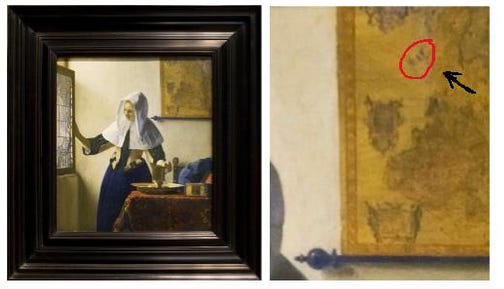

I made a date with Breyten for immediately after the PEN congress was over, hoping to pursue some of the themes he'd raised, but by the time we got together, he was almost all talked out. "Too much, too much," he pleaded, "I'm getting bilious at my own thoughts." So, instead, we set off for a walk through the park (it was a brisk, clear midwinter's morning) over to the Metropolitan Museum. There we meandered aimlessly and mostly silently through the halls, until we drifted into the room with the Vermeers, where Breytenbach came to a sudden halt before the one of the woman in the blue dress, her hand poised upon a silver pitcher. Maybe she's pregnant, but its hard to tell. On the wall behind her hangs an unfurled map. Light pours in from the window, the very essence of lucid grace and tranquility.

Breytenbach gazed silently at the image for a long while, finally letting out a deep sigh. "Look at the date," he said (1660). "It's hard to believe that from all that serenity. emerges the Boer. Look," he continued, a finger stabbing at the map in the background —a map, one suddenly realized, of the coast of Holland, tiny boats bobbing off the shore— "that's them leaving right now!"

OVER THE YEARS (for we subsequently entered into a sort of far-flung friendship, meeting now and again, here and there, in Paris, in New York, in Spain, in Dakar, and finally in South Africa, where I joined him for a brief tour of his old haunts) that moment in front of the Vermeer often returned to me, in part because it proved so anomalous. Breytenbach tends to downplay the European roots of contemporary Afrikaner culture, emphasizing instead its African or, at any rate, mongrel origins. Once I asked him when his people had first set foot in Africa.

"Oh, millions of years ago," he replied, smiling, “just like yours."

After a bit more prodding, he conceded that the first appearance of the name "Breytenbach" in the Cape's historical record occurs in 1656, just four years after the Dutch East India Company founded its small colony on the sheltered slopes of Table Mountain (and another four, for that matter, before Vermeer’s painting), in the form of one "Coenrad Breytenbach," who was immortalized as a minor military figure sent out to retrieve some wayward cattle. To the extent it's been possible to trace that Breytenbach South Africa branch of the family line farther back, it appears if anything to have been German or Alsatian, perhaps Belgian, rather than Dutch in origin.

Breytenbach's mother's family, the Cloetes, were for their part originally French or Flemish. They arrived very early on in the history of the Cape Colony, probably in flight from religious persecution, and their name was associated with the colony's first vineyard. The "Cloete" name quickly became a very common one in the Cape, denoting both rich landowners and the mostly East Asian slaves they imported (and to whom they assigned their own surname); and it's by no means obvious from which side of the divide Breyten's mother's Cloetes derive. Nor, for that matter, was the divide itself all that clear-cut in the olden days. Subsequent Afrikaner fantasies of racial purity notwithstanding ("Mongrels often have a big hang-up about identity," Breyten notes, "and precious little tolerance for ambiguity"), there was a good deal of racial intermixing in the early Cape ("It's a shame they didn't just keep on interbreeding like that," Breyten muses, "it would have saved us all a lot of trouble down the line"). The very term "Afrikaner" originally connoted not "white" or "European" but rather the product of such mixed liaisons.

As for the Afrikaner language, Breytenbach likewise insists on its creole essence. Its richness, at any rate, can hardly be subsumed, as some Afrikaners contend, under the simple rubric of "a daughter-language of Dutch." It's precisely "kitchen-Dutch," the language that arose in the space between the original colonists and their imported slaves, and its riches—the very splendors in which Breyten's poetry so continuously revels—are largely slave riches.

Not that his own family spent much time thinking about such things as he was growing up. Despite what one sometimes reads about Breytenbach (for example on the jacket notes accompanying some of the American editions of his own books), his family was not particularly "distinguished" in lineage and certainly not in worldly station. If anything, Breyten was born…

And so forth: The story goes on for some forty thousand words (a true old-style New Yorker stemwinder)—and believe me, it’s a doozy, beginning with Breyten’s upbringing in a lower class rural Afrikaner family, alongside two brothers, one of whom would grow into a top commander in the Afrikaner regime’s fearsome foreign commando forces, the other a farflung international photographer with his own shady links to the hardcore apartheid regime’s secret services. Breyten, the artistic soul, enrolled at (English, not Afrikaans-speaking) Capetown University before decamping up north, to Paris, where he began composing vivid poetry in his native Afrikaans which almost immediately caused a sensation back home, for these poems, when not politically explosive were proving among the most gorgeously sublime love and specifically erotic lyrics ever conceived in the language, and among the most scandalous, since they were being written in an exile enforced by the fact that Yolande, the new wife they were celebrating, was Vietnamese, which is to say a woman of color, a circumstance that veritably fried every circuit in the Afrikaans nationalist sensibility, which in turn probably helped account for the terrible prison term (over nine years, a large part in solitary) he’d presently get meted after he’d returned to his native country in disguise in an attempt to make clandestine contact with Steven Biko and his independent oppositionist comrades. (The actual story of Breyten’s arrest and the period leading up to the trial, the sick twisted interaction between the Afrikaner intellectual given control over the cowering prisoner across months of interrogation, culminating in Breyten’s utter prostration at the trial itself, notwithstanding which, double-crossed among others by his own brothers, he’d still been given a maximum sentence—all of it would make for a harrowing chamber drama within the wider story of his life). ”Looking into South Africa,” he had written years earlier, “is like looking into the mirror at midnight when one has pulled a face and a train blew its whistle and one’s image stayed there, fixed for all eternity: A horrible face but one’s own.” Indeed. And yet somehow he and Yolande survived both the calamity of the trial and the seemingly endless ensuing sentence, and though one might have thought the entire dismal experience would have cured Breyten of political engagement once and for all, on the contrary, once out, he poured himself right back into the fray and in fact went on to prove a decisive figure, working from abroad, in the transition out of apartheid, even though once that transition had occurred and he began making regular return visits to his homeland, he proved highly critical of the turn the transition was taking under the ANC (“Only anarchy can save us from chaos now,” he used to proclaim, with typically sardonic brio), retaining his role as an exquisitely discomfiting gadfly to the very end. Anyway, trust me, that’s barely the half of it. At length though, my own 1993 piece concluded like this:

Coda

A FEW DAYS LATER {this was now in the early nineties}, I joined Breyten and Yolande in a stout stone farmhouse in the hills outside a small town a few hours' train ride north of Barcelona. It was strange the way that, after so much far-flung history, the three brothers had managed to secure virtually identical views from their kitchen windows—an overgrown orchard, the swell of shrubby hills in the mid-distance, the wide sky above, an arid valley falling gently away down below.

Yolande was excited: for the first time since girlhood, she had become fascinated by her own roots, and in a few months' time she and a friend were going to be making a trek back to Vietnam. Breyten seemed pleased by the role reversal. Meanwhile, he was busy in a small painting studio he had had built over the garage: during this last South African trip, he had made the final arrangements for an exhibition of his paintings the first ever in his homeland—to open that December.

Evening was coming on, and Breyten and I were out back, watching the setting sun blond the surrounding hills. I heard a pair of mellow hoots off in the distance. "Owls?" I asked.

"No," Breyten said, smiling. "Wood pigeons, probably. But we do have owls here. And crows. And quail and nightingales. Well, we have everything." From there he free-associated to Pretoria and the birds that had sustained him in prison. "That's one thing about spending a long stretch in prison," he commented. "You never really get out afterward: part of you is continually being drawn back in."

We were silent a few moments: the sun descended, the light deepened. I asked him whether he ever looked back cringingly on his behavior during those days. "Oh, sure," he said. "There are aspects of my behavior that still leave me appalled. But I also remember that that's what they're continually programming you for— you're being conditioned for self-destruction, they're lacing you with self-disgust, you're being made guilty. The whole process is a continual rape of one's own better instincts. So that, sure, it leaves its scar tissue thick across one's sense of self-worth.

"And yet, in a way, I have more confidence in myself than that. Damn it all, so I wasn't able to be perfect. Self-knowledge is not self-abasement or self-rejection. I was, I am, a flawed human being. But that's more interesting than being an iron cast. And there's something to be said for fucking up. In fact, fucking up, if you aspire to be an artist, may be the great creative principle: getting broken, broken wide open, and then delving among the shards. Moving on. Painting, writing— these are always, first and foremost, struggles for authenticity."

The sun had set and the world had suddenly gone quite dark. We went back inside. Some of his old gallery-show catalogs were strewn across the kitchen table: research for his forthcoming South African exhibition. And one of them happened to be open to Family Portrait—his triple self-portrait. I smiled, pointing to it.

"Ah yes," Breyten concurred. "We had a kid here the other day, and he was looking at that picture, and he asked me why the bird-hand of the old man kept bothering the little boy." He laughed. "I liked that."

I asked him how he himself felt about that picture nowadays.

"Oh," he said, "you know how it is. That's me, dead at the age of nine. Me, dead at the age of thirty. Me, dead at the age of forty...." (The rumble seat, the goldfish pond, the field plowed under.) "I have sympathy for all of them, as I do for any dead. But they are not me."

*

Here are some photos of Breyten and Yolande from over the years, from their earliest bohemian days in Paris, a shot from shortly after he was released from prison, and then a few more recent vantages:

Quite an epic in its own right, that sixty-plus-year romance, and the daughter Daphnée and two grandsons it presently yielded.

I wish I could include some of Breyten’s poetry, but, as I say, I am still in Europe, away from my library, and I am not too happy with what is available online, so maybe I’ll hold off for the time being and compile a little selection when I get home.

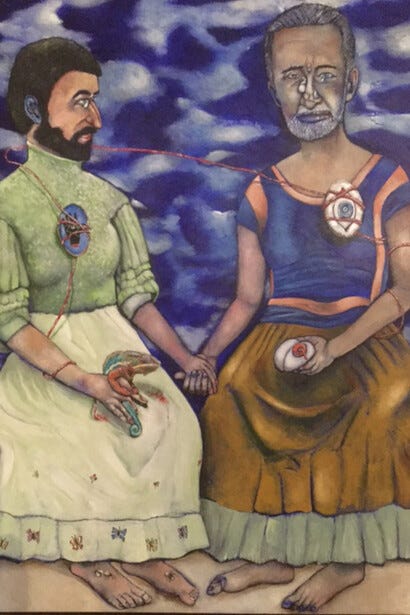

As for his paintings, there’s a bit more of a selection online, so do take a gander. Hieronymus Bosch as filtered through a Matissean or perhaps Hockneyesque palette. By turns disconcertingly surreal, impishly sly, and then just plain succu-luscious. Here below I include some photos of my own of some his more recent paintings (it was as if he were making up for lost time, these past dozen years). Self portraits (and details of same):

And portraits of others:

J.M. Coetzee, Cervantes, and for some reason a rooster—and my favorite (below), his heroes Walter Benjamin and Franz Kafka (in a canvas Breyten titled Punishable Innocents):

And then combinations of the two (self-portraits embedded in portraits of others):

Finally, for now, I wanted to give you a sense of Breyten’s voice, which was perennially heart-melting (no wonder, I used to think, that he got into so much trouble, if that was the inner voice plying him with fresh ideas). At one point during the seven years I was working, on and off, on my New Yorker profile of Breyten, I was invited by LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art to collaborate with the producer Stephen Erickson on a half hour episode of their Territories of Art audio series, in this instance based in large part on my recordings of conversations with Breyten. You can listen to the whole thing here but in particular I wanted you to be able to experience Breyten’s reading of one of the poems he smuggled out to Yolande from prison (in Erickson’s braiding of both the original Afrikaans, which Yolande would not necessarily have understood, and Breyten’s own English translation) followed by his reflections on the sensorium of prison life, the melding of sight and sound, culminating in one of the all-time great radio moments—well, see/hear for yourself HERE. (Note: In both cases, it may be necessary to drag the cursor slightly to the right to jumpstart the audio.)

*

Okay, so let’s let that be it for now. I have a feeling Breyten will be making further appearances in the Cabinet, his voice is so vital, his vision so clear, his presence so welcome.

Meanwhile: Love Life.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

Thank you so much for this wonderful piece. I thought I'd share this essay "Herinneringe aan my oom Breyten" – "Memories of my uncle Breyten" (sorry, it's in Afrikaans) – by his niece Anna-Karien Otto, in which she also recounts her meeting with you when you were writing The New Yorker article. https://www.litnet.co.za/herinneringe-van-my-oom-breyten/