WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

A few thoughts on the current pass, in the wake of last week’s dismal election, followed by a guest column from Seattle art writer extraordinaire Jen Graves.

* * *

THE CURRENT PASS

So, a guy goes to see the rabbi, who has an apprentice rabbi sitting in on the meeting, and the guy goes off on his wife, how horrible she is and inconsiderate and profligate and so forth, and at length the rabbi tells the fellow, “You know what, you’re absolutely right,” and the guy leaves completely satisfied. A few hours later, the wife arrives, and now she tears into her husband, contradicting his every claim and supplying all sorts of countervailing instances, and at length the rabbi tells her, “You know what, you’re absolutely right,” and she too leaves, completely satisfied. At which point, “But wait a second,” the assistant rabbi challenges his master, “the two of them came in here making diametrically opposite claims and you told each of them that they were absolutely right, and that’s impossible, they can’t both be right.” The rabbi rubs his chin, sagely, considering his apprentice’s argument at length before eventually responding, “You know what, you’re absolutely right.”

Which is kind of how I feel about the various contending autopsies on the recent campaign, especially from the vantage of my ongoing current travels abroad. I mean, I found the divine Natalie Wynn’s piece no less plausible than the sage Andrew Sullivan’s (as usual I agree with much if not all of what each says) and I likewise agreed with Peter Singer and Doug Henwood and on a separate track found Juan Cole’s Middle East tangent especially cogent, and so forth. In sum, there’s a lot to go around and a whole lot to mull. A piece by Aaron Blake in The Washington Post firmly demurring from the tidal claims of an unprecedented Republican mandate seemed to me particularly important: Trump’s electoral vote total was barely larger than Biden’s last time and in fact less than that of 9 of the last 16 presidential winners (going back to JFK in 1960); the precentage by which he captured the popular vote lead, for that matter, was about half of Biden’s last time, and less than that of 11 of 16 of those same such winners. And so forth. Yes, the Republicans look like they will have control of the executive and both sides of the legislative and the Supreme Court, at least for the next two years, though the next election (so long as there is going to be one, conducted in any semblance of fair fashion—admittedly a big “if”) will likely favor the Democrats (for starters, next time it will be the Republicans having to defend the greater portion of Senate seats, rather than this time’s other way around, and the inflationary pressures of a whole slew of Trump programs will have likely begun to kick in). Anyway, I have not that much more to add in the immediate term.

* * *

THE MAIN EVENT

GUEST CABINETMAKER: JEN GRAVES

As I say, I’ve been travelling these last few weeks and will still be doing so the next few, so I thought this might be a good time to hand the keys to the Cabinet over to a guest contributor, one of my favorite art writers at that, Seattle’s own Jen Graves.

Or perhaps I should say an ex-arts writer, or semi-ex at any rate, since it was one of the great and sorry exasperations of the past decade when she announced her retirement from her Pulitzer-finalist seat atop the Seattle Stranger, as that paper, like so many independent regional venues, kept shrinking and shedding coverage and columnists. Aye. As it happens, and as she relates here, even though Jen took on a whole new career, she couldn’t quite stop chronicling her wide-ranging cultural responses in a substack of her own, a case in point being this very piece here, which she only just filed and which I suspect will find a congenial response among the dear frequenters of this compendium of ours. So, without further ado, Ms. Graves:

On that particular day on the crosstown bus, I remember that I felt alone, separate, disconnected, and I was convinced that, actually, I also was those things. But something happened instead.

This was autumn 2019. It had been more than two years since I’d left my job as a semi-public figure, writing about art for nearly twenty years for newspapers. I had started that job when I was barely 20 years old, and I had used it to create a self, a self that got bigger and stronger over time. She won accolades and awards, she got better jobs. Meanwhile, she distracted herself from the fact that every job she left went dark. The infrastructure upholding the jobs was crumbling while the self was swelling. It was only a matter of time before the fall.

Relief was part of how it felt to shatter my old self, to throw her to the ground and notice me still standing. For one thing, I was released from the haunting of the cautionary tale I witnessed growing up, watching the ways my father’s identity as a sportswriter dominated how he felt about himself. He was locally famous, the kind of guy other guys recognize in a bar and offer to buy a beer, known in our area to the point that high school dates of mine would say, “Your dad is ‘Matt Graves Selects’?” Most of all my father mattered to himself because he had that job. In backstage moments, I caught glimpses of how terrified he could feel about that, how vulnerable, how contingent. I watched the teetering of his built-up self, and I was scared.

In the years between when I walked out of public writing and when I sat down on that crosstown bus, I had gotten a master’s degree in therapy, and I was a few months into my new career. I was in the process of building a new self, one I would not be so afraid of losing (a process of doing and undoing that continues apace). It was the middle of a weekday, and I was on a break from work for a doctor’s appointment. Walking from my gynecologist’s office in downtown Seattle to the bus stop headed for home, I passed a gallery showing a series of paintings and sculptures by someone I knew and had written about multiple times. I still loved all forms of art desperately, congenitally, yet generally I avoided going to exhibitions of art in my former public zone, because I just didn’t know how to show up anymore. My legs, probably still bearing traces of wiped-away speculum lubricant, walked me into the gallery without the full consent of the rest of me. My body wanted to see the art, evidently, even if my mind wasn’t sure how to be in a gallery anymore.

What I remember feeling is stunned to tears by the art: taken in, loved, seen, known. That old mystery again! How is it possible that one person arranges a series of items in such a way that the resulting object, left behind in a room, then enters the force field of another person to become feeling? This is perhaps my favorite thing about being a person, the greatest and most infinitely absorbing of all puzzles for me. When I see myself in something else I stop feeling like an isolated self. No surprise that I found myself on the crosstown bus headed home pecking away compulsively, clicking “Share” on Instagram with a little thrill. This was the thrill I’d had all those years ago when I began responding to art with little word-creations of my own, before doing it became my job, my income, my working conditions, my everyday, my health insurance, my unpaid maternity leave, my built-up self. This was the stuff. All that other bullshit had not killed it. It was not killable.

Below is one of the paintings I encountered that day, which in real life stands five feet tall and four feet wide — large enough to fill an entire field of vision, pushing away all else. The painting is currently up at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, along with its nine siblings, which I also saw that day, all of them abstractions of the same size and bearing the same silent, buzzing intensity, generated using only small marks made in white ink on black clayboard by Mary Ann Peters, whose own questing and courage as a creator spurred me to share such an intimate thing from that bus that day.

I wrote:

A few weeks ago my doctor sent me for an ultrasound to check out a mass that turned out to be two different masses, one harmless and the other most likely harmless. Bloodwork being analyzed at the same time, my minuscule particles being filtered and photographed, blown up and analyzed, revealed something similarly noteworthy yet indeterminate: I am perimenopausal, meaning I am in a stage of life that is between two other stages of life that are better defined. This means something, I’m just not sure yet what. I will be able to map it when it’s past, but while I’m living it in my body, it will continue to surface in the form of blurry fields of indistinguishable signal and noise, syndrome-like. It was in the immediate aftermath of this experience that I entered the most recent show of Mary Ann Peters, whose images are constructed out of her research into the places on this earth where masses of migrants from Syria are living in limbo, in blurry motion. The artist, whose own family migrated from Syria in the last generation, painted and sculpted visions of lands where there may or may not be identifiable events occurring, there may or may not be oases at which to rest and replenish. In the front room there are paintings of places where I can identify some small, everyday event, like a pair of birds convening or a wind gusting up or a man and a dog passing each other in a desolate place where neither belongs. But the line between figure and abstraction is wiggly. …By the time we reach the back room at the James Harris Gallery, we are inside the earth itself, faced with paintings made of nothing but white marks on a black ground. Yet they pulse with the promise of discovery. What here is signal and what is noise? What is negative space versus something solid, something of note, something that needs attention? Peters prompts the looking, spreads the urgency of trying to find out more. Of needing to know more.

There was a time in my life when what I wrote mattered for material reasons. My writing paid my bills. Sometimes it helped pay the bills of artists I wrote about. Other times it told people where to go and when; it was a thing of use. This time, that day five years ago, I sent those words out into the world for no reason at all. Seeing those paintings, I felt seen myself, and because that still feels like a miracle to me, I couldn’t help writing something down and sending it out. I was okay with those words going nowhere and doing nothing. But then they surprised me and did something, and it reminded me of something I had almost forgotten.

I’m showing this picture to demonstrate: It’s Mary Ann Peters, the artist who made those paintings, reading the words I wrote on Instagram that day out loud in a movie. Out loud. In a movie.

The movie is by Mary Louise Schumacher. Schumacher was an art writer in Milwaukee before she was a filmmaker. She lost her newspaper art-writing job in the same late-stage-capitalist media churn I did, so she had her reasons for making a movie about it. For ten years, Schumacher followed a handful of art writers all over the country and asked them why they did what they did, and whether and why it mattered to do it, since we were getting laid off every which where. Did anybody care? She followed me through my own layoff and into the maze of my aftermath, including filming me while I stomped down trash in the dumpster at an office building where I was a cleaning lady the year before I went back to graduate school. Schumacher called the movie Out of the Picture.

Out of the Picture premiered at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and shows for the first time in Seattle next month at the Frye Art Museum, which, again, is exhibiting those incredible paintings by Peters at the same time. The movie asks: What is art writing for? Why do we do this, anyway?

I’m not sure how to answer those questions for other people, but this experience from that day five years ago helps me answer them for me. On that day, I sent those words out into the universe expecting them to die on contact with the world, and I was okay with that. I was writing with no obligation: no assignment, no byline, no built-up self anymore. It was just that, seeing those paintings, I felt seen myself, so I made something myself, and on it went. The paintings, that moment on the bus, the words, me, the artist, all these parts of the world taken notice of were sewn together to live another day. I find I am not alone, separate, and disconnected after all, even though I can feel like it. Hello, you. Oh, hi.

Layoffs and journalism death spirals be damned, this is what actually matters about what artists and filmmakers and writers do: we sew back together what’s been torn apart, which is ourselves, each other, this place, this time. We mend. It shouldn’t even need explaining, but in this crazy time, there it is, I guess. I’ll be at the Frye the night the movie plays to talk about it afterward and maybe you can come up and say hello, and I can say hi. And who knows what will be mended and made after that.

Out of the Picture screens at the Frye Art Museum on December 12 at 5:30 pm. It’s free but you need to get tickets here.

And for that matter, subscribe to Jen Graves’s “Still Looking” substack site for further regular doses of writing every bit as good and vital and gripping as that.

And in the meantime, breathe in, breath out, recombobulate: the Great Work goes on.

* * *

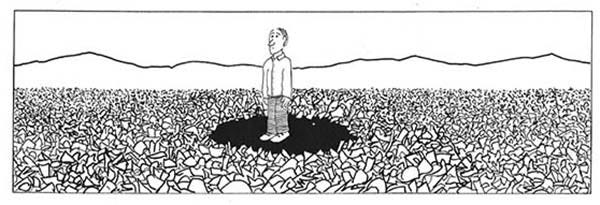

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

?

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

Thank you for pointing me towards Jen Graves.