WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This week, for starters, the response my modernist composer grandfather Ernst Toch sent to a young Kansas City composition student who’d sent him a piece of his own, asking for his advice regarding same; opening out from there, speaking of questions of form, onto a whole trill of entries about boats and trees.

* * *

The Main Event

A Bad Day for the Young Composer

About fifty years ago (good lord), when I was helping my grandmother Lilly sort through the papers of my grandfather Ernst Toch as we prepared to deed them to the UCLA Music Library’s recently established Toch Archive, we came upon a carbon copy of the letter below, which Ernst in turn appears to have sent to a young would-be composer from Kansas City named Russell Webber who had sent him a score he had recently produced, asking for Ernst’s expert opinion. In response, young Mr Webber may have gotten well more than he had been counting on:

Jan. 14, 1949

Dear Mr. Webber:

I have tried my very best -- in all conscientiousness -- to help you. I must go one step farther, even at the risk not to be fully understood by you, who I do not know personally; though I hope you will understand and believe me if you, too, do your best, follow all my remarks equally conscientiously and without sensitivity and vanity, just as you would trust and submit to the diagnosis of an experienced doctor, even though it may hurt at the moment. There is no other way to real help.

Your case is by no means hopeless; let me anticipate this. On the contrary, you show definitely a certain musical imagination and a natural leaning, even gift; your choice of a musical form which probably is the hardest to master, speaks for the earnestness of your ambition and musical taste. But you lack completely even the most fundamental and primitive bases of knowledge, in every direction. And unavowedly, you betray even your subconscious (or conscious?) awareness of this deplorable status of your knowledge or lack of knowledge. What you really mean to compose is a fugue -- why resort to subterfuges and excuses? But somehow you feel your incompetency; so you call it bashfully, pretending modesty, a "Fugato.” In doing so, you try, unconsciously or half-consciously, to invite leniency on the part of the expert, your possible critic. You try to cover up your shortcomings before yourself; you try to deceive yourself. Why? I am sorry I have to tell you it is far from being a "fugato" as well -- if we ever should admit such a principal difference other than in size or weight; but a fugue, collapsing in its very fundaments right from its start to the whole of its ill course, does not make a "fugato" either. Complete insufficiency does not enter the meaning of the term. Nor can I help having the same feeling as to your psychic reasons for calling the customary Prelude, bashfully again (and ornately at the same time) "Entrada" (or "Intrada," as you write). The reason for its shortness is no other than the fact that your muse deserted you deplorably prematurely, leaving you in the barren field without knowledge, where to turn or what to do; so you jump incoherently -- incoherence is the paramount feature of your whole composition -- into the motivical, or preparatory, announcement of the fugue theme (good as this is in itself).

Let me make a comparison. You take a piece of cloth (we will skip the question if this piece of cloth, or material, is good in itself; it may be at least workable, anyway) and decide to make a suit of it for yourself. It turns out that the suit is no good. One trouser is as much too long as the other is too short; the same with the sleeves; one of them besides, is sewed in upside down; the lining appears on the outside instead of inside; the pockets are in the back; no two buttons are alike in size or colour etc, etc, etc. What are you going to do, instead of the only reasonable thing, namely, to throw it into the fire and learn first how to tailor? You try to think of the best tailors in the country and mail the miscarriage to one of them, or to some of them, expecting them to remedy the calamity.

I assure you, the only way of "correcting" your composition for me or any composer of my standards would be to recompose the whole thing from the first to the last bar; and, of course, you cannot expect to find any such composer to do that. Speaking of coherence: A composition must grow organically, like a tree; there must be no seams, no gaps, no foreign matter; the sap of the tree must pass through the whole body of it, reach every branch and twig and leaf of it. It must grow, grow, grow, instead of being patched, patched, patched, unorganically. Instead of putting pieces of a whole together, as I say, uncoherently, you must let them grow out of one another, join them coherently, overlap their limbs or sections, instead of letting them dangle in the air miserably. I say again, read my book [The Shaping Forces in Music], read it very attentively; study it; most of all the section "Form," especially Chapter XL "The Art of Joining," follow closely all analyses. (I am sure you can get the book in your public library; it appeared last July.) Also in the section "Melody" you will find much you need badly. Your orchestration is just as wanting. It must help to clarify a fugue by opposing the various sections -- woodwinds, brass, strings; let only one of them play at a time, joining them gradually and keeping them transparent all the time, being always intent on the plasticity of the piece (for which, to be sure, it first has to be composed accordingly). Your orchestration is most of the time a muddle, just the opposite of plastic. Summarizing: What you need is to study, to study hard, to study still harder. Listen to good music as much as you can, copy master scores with open eyes and ears; listen while reading the score.

Believe me, I spent the better part of a week with your score. If I would charge you at the rate of my teaching fee, it would cost you a fortune. As it is, and since, in spite of my best will, I might have caused you some disappointment, maybe even some personal hurt (which I could not help and which, I am sure, will still turn out for the better to you if you take to heart everything I told you and read everything in the score and in the letter carefully), I will not even refer to my first letter and just forget about the balance. I will admit that much is performed now a days which is not much of a composition either. But this fact cannot change my standards and should not influence yours either, if you take art seriously, as everyone must do who seeks real achievement and accomplishment.

Sincerely,

*

On first reading, that letter must have been completely devastating. But on the other hand, it today strikes me at the same time as having been extravagantly generous, which may have had something to do with the occasion of its generation. January 1949: for the previous fifteen years, newly settled in Los Angeles in flight from Hitler, Toch (at one time amongst the leading composers in the incredibly dynamic modernist Weimar scene from the end of World War I through the rise of the Nazis in 1933) had had to largely abandon his own compositional activity as he poured himself into film composing in Hollywood and the teaching of composition both at USC and privately, the better to raise funds to provide affadavits for as many family members and friends, likewise attempting to flee the gathering holocaust, as he possibly could. With the end of the war, he was forced to recognize how scattershot those efforts had proven (fully half of his sixty-four cousins had perished in the camps, not to speak of all the others), and yet, partly in response to all of that devastation, his own compositional juices began once again to surge, now struggling for purchase amongst all his other professional obligations. In October 1948, he suffered a massive heart attack which almost killed him, after which he resolved to give up both teaching and film-composing. It was into that vortex that Mr. Webber had unknowingly stumbled, with his request, and out of it that Ernst seemed to have been responding. In some ways the letter seems like one last expression of what had also been a remarkable teaching facility (also evinced in the book he refers to, The Shaping Forces of Music: An Inquiry into the Nature of Harmony, Melody, Counterpoint and Form, which he had published just the year before).

Toch’s final fifteen years would prove his most prolific, encompassing among other things seven symphonies (the third of which garnered the Pulitzer Prize), an opera and innumerable other works for orchestra and chamber groups. For his part, it appears that Russell Webber went on to a distinguished career as a violinist, composer, and professor in his own right, at Kansas City University. His works for violin were performed by the likes of Zino Francescatti and Roman Totenberg (NPR Nina’s father!)—or so I was eventually able to establish by tracking down his obituary in the Kansas City Times. He died, of a heart attack, at the age of 62, in Kansas City, in 1963—as it happens a year before Toch himself died.

If anyone reading this happens to know anything about the disposition of Mr. Webber’s estate, it sure would be great someday to see his side of the correspondence, as well as the copy of his Fugato as marked up by Toch. You know where to find me.

Meanwhile, I have written elsewhere of the way in which I myself inherited none of my grandfather’s musical capacities, and yet how powerfully resonant his writings have proved for me in my own writerly vocation and teaching, especially his formulations regarding form itself. Ernst used to speak of music as an expression of the architectonic—which is to say form across time as opposed to architecture, which is form across space—a quality it shares with narrative writing and reading (which in that sense are much more like the experience of music than like, say, painting, or at any rate the experience of a completed painting). And as in the letter to Mr. Webber, he also always insisted that that form should grow organically, whereupon he often had recourse to that metaphor of a tree (a melding of the architechtonic and the organic if ever there was one). A metaphor I, too, often had recourse to in my teaching, along with that of building a boat (which I think I also got from him).

* * *

PERTINENT PASSAGES FROM MY COMMONPLACE BOOK

From Sacred Hunger, Barry Unsworth’s remarkable 1992 novel of the Atlantic slave trade, the start of chapter eight, where, as it happens, he is describing the building of what will become a slave ship:

Work on the ship continued; she rose on her stocks from day to day, proceeding by ordained stages from notion to form. Like any work of the imagination, she had to maintain herself against disbelief, guard her purpose through metamorphoses that made her barely recognizable at times—indeed she had looked more herself in the early stages of the building, with the timbers of the keel laid in place and scarphed together to form her backbone and the stem and sternpost jointed to it. Then she had already the perfect dynamic of her shape, the perfect declaration of her purpose. But with the attachment of the vertical frames, which conform to the design of the hull and so define the shape of it, she looked a botched, dishevelled thing for a while, with the raw planks standing up loose all round her. Then slowly she was gripped into shape again, clamped together by the transverse beams running athwart her and the massive wales that girdled her fore and aft. She was riveted and fastened with oak trenails and wrought-iron bolts driven through the timbers and clenched. And so she began to look like herself again, as is the gradual way of art.

*

Kay Ryan’s 2006 poem:

We’re Building the Ship as We Sail It

The first fear

being drowning, the

ship’s first shape

was a raft, which

was hard to unflatten

after that didn’t

happen. It’s awkward

to have to do one’s

planning in extremis

in the early years—

so hard to hide later:

sleekening the hull,

making things

more gracious.

* * *

TREES, FELLED AND RESURRECTED

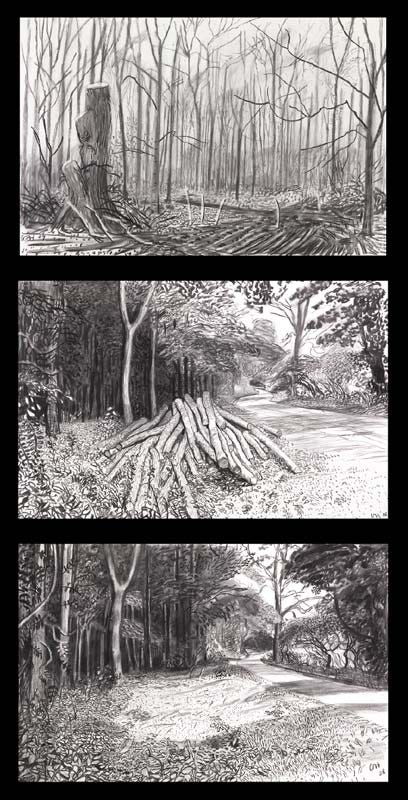

First off, a passage from my catalog essay for a show of then-recent work by David Hockney at the Pace Gallery in New York in 2009, regarding a series of drawings and subsequent paintings that Hockney had rendered after coming upon a beloved patch of scrub forest, including one particular totemic stump, near his Bridlington compound in Yorkshire, that had only just recently been systematically thinned out:

He pulled out a pad and began to sketch it in charcoal (secretly charmed by the notion that here he was using burnt dead wood to render images of other more recently felled dead wood onto sheaves of stretched pulped wood), returning several times over the next few days for further sketches, whereupon he came to realize that the chopping down of that particular tree had been part of a wider project, a once-in-a-generation pruning back and thinning out of the entire grove, with rows of felled logs piling up along the roadside. “I was just lucky,” he admits, considering the veritable trove of fresh imagery he had stumbled upon, “but then, at root, I am always an opportunist, simply responding to whatever happens to come my way.”

The ensuing sequence of charcoal sketches and their resultant paintings would indeed prove exceptionally evocative: formally so, to be sure, with their good strong horizontals set against the soaring verticals of the surrounding grove, but thematically as well. A veritable floodtide of mortality, piling up ever higher (“Felled Trees on Woldgate,” “Fresh Timber,” “More Crooked Timber on Woldgate,” “Arranged Felled Trees,”) and then carted away, (“Astray,” “Little Left”), until it was as if the logs had never even been there at all, except that their absence, captured in a final charcoal drawing (“Timber Gone”) now constituted perhaps the most haunting presence of all.

*

Which in turn at the time put me in mind of the obverse exercise of someone else’s imagination, W.S. Merwin’s incantorarily self-evident prose poem “Unchopping a Tree” from his The Miner’s Pale Children collection, first published in 1970, right around the time of the first Earth Day, though revisited in various forms, including in a stand-alone book illustrated by Liz Ward, and as inspiration for a short passage from a 2011 video from a 2011 video announcing Maya Lin’s“What is Missing?” project.

Start with the leaves, the small twigs, and the nests that have been shaken, ripped, or broken off by the fall; these must be gathered and attached once again to their respective places. It is not arduous work, unless major limbs have been smashed or mutilated. If the fall was carefully and correctly planned, the chances of anything of the kind happening will have been reduced. Again, much depends upon the size, age, shape, and species of the tree. Still, you will be lucky if you can get through this stage without having to use machinery. Even in the best of circumstances it is a labor that will make you wish often that you had won the favor of the universe of ants, the empire of mice, or at least a local tribe of squirrels, and could enlist their labors and their talents. But no, they leave you to it. They have learned, with time. This is men's work.

It goes without saying that if the tree was hollow in whole or in part, and contained old nests of bird or mammal or insect, or hoards of nuts or such structures as wasps or bees build for their survival, the contents will have to repaired where necessary, and reassembled, insofar as possible, in their original order, including the shells of nuts already opened. With spider's webs you must simply do the best you can. We do not have the spider's weaving equipment, nor any substitute for the leaf's living bond with its point of attachment and nourishment. It is even harder to simulate the latter when the leaves have once become dry — as they are bound to do, for this is not the labor of a moment. Also it hardly needs saying that this is the time for repairing any neighboring trees or bushes or other growth that might have been damaged by the fall. The same rules apply. Where neighboring trees were of the same species it is difficult not to waste time conveying a detached leaf back to the wrong tree. Practice, practice. Put your hope in that. Now the tackle must be put into place, or the scaffolding, depending on the surroundings and the dimension of the tree. It is ticklish work. Almost always it involves, in itself, further damage to the area, which will have to be corrected later. But, as you've heard, it can't be helped. And care now is likely to save you considerable trouble later. Be careful to grind nothing into the ground.

At last the time comes for the erecting of the trunk. By now it will scarcely be necessary to remind you of the delicacy of this huge skeleton. Every motion of the tackle, every slightly upward heave of the trunk, the branches, their elaborately reassembled panoply of leaves (now dead) will draw from you an involuntary gasp. You will watch for a leaf or a twig to be snapped off yet again. You will listen for the nuts to shift in the hollow limb and you will hear whether they are indeed falling into place or are spilling in disorder — in which case, or in the event of anything else of the kind — operations will have to cease, of course, while you correct the matter. The raising itself is no small enterprise, from the moment when the chains tighten around the old bandages until the bole stands vertical above the stump, splinter above splinter. Now the final straightening of the splinters themselves can take place (the preliminary work is best done while the wood is still green and soft, but at times when the splinters are not badly twisted most of the straightening is left until now, when the torn ends are face to face with each other). When the splinters are perfectly complementary the appropriate fixative is applied. Again we have no duplicate of the original substance. Ours is extremely strong, but it is rigid. It is limited to surfaces, and there is no play in it. However the core is not the part of the trunk that conducted life from the roots up to the branches and back again. It was relatively inert. The fixative for this part is not the same as the one for the outer layers and the bark, and if either of these is involved in the splintered sections they must receive applications of the appropriate adhesives. Apart from being incorrect and probably ineffective, the core fixative would leave a scar on the bark.

When all is ready the splintered trunk is lowered onto the splinters of the stump. This, one might say, is only the skeleton of the resurrection. Now the chips must be gathered, and the sawdust, and returned to their former positions. The fixative for the wood layers will be applied to chips and sawdust consisting only of wood. Chips and sawdust consisting of several substances will receive applications of the correct adhesives. It is as well, where possible, to shelter the materials from the elements while working. Weathering makes it harder to identify the smaller fragments. Bark sawdust in particular the earth lays claim to very quickly. You must find your own way of coping with this problem. There is a certain beauty, you will notice at moments, in the patterns of the chips as they are fitted back into place. You will wonder to what extent it should be described as natural, to what extent man-made. It will lead you on to speculations about the parentage of beauty itself, to which you will return.

The adhesive for the chips is translucent, and not so rigid as that for splinters. That for the bark and its subcutaneous layers is transparent and runs into the fibers on either side, partially dissolving them into each other. It does not set the sap flowing again but it does pay a kind of tribute to the preoccupations of the ancient thoroughfares. You could not roll an egg over the joints but some of the mine-shafts would still be passable, no doubt. For the first exploring insect who raises its head in the tight echoless passages. The day comes when it is all restored, even to the moss (now dead) over the wound. You will sleep badly, thinking of the removal of the scaffolding that must begin the next morning. How you will hope for sun and a still day!

The removal of the scaffolding or tackle is not so dangerous, perhaps, to the surroundings, as its installation, but it presents problems. It should be taken from the spot piece by piece as it is detached, and stored at a distance. You have come to accept it there, around the tree. The sky begins to look naked as the chains and struts one by one vacate their positions. Finally the moment arrives when the last sustaining piece is removed and the tree stands again on its own. It is as though its weight for a moment stood on your heart. You listen for a thud of settlement, a warning creak deep in the intricate joinery. You cannot believe it will hold. How like something dreamed it is, standing there all by itself. How long will it stand there now? The first breeze that touches its dead leaves all seems to flow into your mouth. You are afraid the motion of the clouds will be enough to push to over. What more can you do? What more can you do?

But there is nothing more you can do.

Others are waiting.

Everything is going to have to be put back.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

The African origins of World War I and a friendly debate about Carl Jung’s The Red Book, which immediately preceded it…

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

The art of unchopping a tree caught at me, a magic...I told my followers of my FB page...that is fast becoming a necessity.