WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This time out, three art pieces. First, one FROM THE ARCHIVES (and peeling off from Issue #14’s piece on the 94-year-old Robert Irwin’s latest show), a “Pillow of Air” on tough old art guys suddenly getting all choked up; and then, in the INDEX SPLENDORUM, a short Russian documentary masterpiece from over half a century ago, on the way art, or at any rate one specific Renaissance painting, cast its spell over files of ordinary museum visitors, and how the way it did so still casts a spell over the rest of us to this day (and raises an important question in the process); and then finally a fresh ARTWALK about encountering another sort of Colossus at the Prado. Followed by that Important Announcement we were supposed to make last time out but got delayed: this time, for real. Please, if nothing else, do give that a look.

* * *

From the Archives

OLD ART GUYS GETTING ALL CHOKED UP

The “Artwalk” entry from a couple issues back, about Robert Irwin’s extraordinary recent show, at age 94, at the Pace Gallery in New York, and then last issue’s conclusion of that five-part “All that is Solid” convergent taxonomy series (culminating in its unified field theory of cultural transmission) got me to thinking about a piece of mine from almost a decade ago, part of a series of Pillows of Air (“Monthly Ambles through the Visual World”) that I was at the time contributing to the print editions of The Believer magazine. This one, from their January 2014 issue started out by invoking a then-recent show of Irwin’s at the Whitney Museum (in its old uptown Breuer building haunts, indeed one of the last such exhibitions held there before their move downtown) and, as it turns out (actually, I’d forgotten this part) ended up landing on someone else’s earlier stab at a unified field theory of cultural transmission of their own. Anyway, here it is:

IRWIN / LONGO / MORANDI / PIERO / SNYDER

A few months ago {again, we’re talking 2013-4 here}, early one midsummer evening, I happened to be up on the fourth floor of the Whitney Museum in New York, experiencing—or perhaps I should say re-experiencing—its restaging of Robert Irwin's legendary 1977 Scrim veil-Black rectangle-Natural light installation, a piece in which the California artist had started out by emptying virtually the entire floor, stripping it down to its barest essentials (the dark slate flooring, the gray hive ceiling, that stark trapezoidal window off to the side) and then bisecting the resulting vast empty space with a shimmering, pearlescent expanse of white scrim, held taut from ceiling down to eye level by a black metal bar, which in turn echoed the black painted stripe Irwin had applied to the perimeter of the rest of the room: that and nothing more.

A piece, in short, that forced one to find one's bearing in the midst of a free fall in one's initial expectations (and to savor the marvel of how one is always having to adjust one's bearings like that: falling, gauging, steadying)—and then, beyond that, that allowed one to experience the sheer hushed marvel of natural light itself, spreading (as if in a Vermeer) like a tide across the scrim-sliced room.

I say "happened to be" there, but actually I was there because a half hour hence, downstairs in the basement, I was going to be delivering a talk on Irwin, the subject of my first book, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, which in fact (in that 1982 first edition) had culminated with a depiction of the original rendition of this very piece. Many of those who would soon be in the audience were likewise milling about, taking in the approaching-evening-tide, and presently I found myself conversing with one of them, a compact gentleman in a leather jacket, who turned out to be the eminent eighties-generation artist Robert Longo, famous, for example, for his startlingly realistic charcoal depictions of snazzily dressed urban men and women, eerily arrested in mid-swoon.

Longo began to tell me a story about the first time he’d met Irwin, back in the mid-seventies, and it was getting to be a good story, so I interrupted him and asked whether he'd be willing to share it with everyone later, down at my presentation. And he said, Alright, sure, okay.

So, about an hour later, downstairs, when I got to the part in my talk where I was describing how across the sixties and into the early seventies Irwin had systematically dismantled all the usual requirements of the art act (image, line, focus, signature, object) till he got to the point where he abandoned his studio altogether and simply announced that he would go anywhere, anytime, in response to any invitation to come talk with anyone about the nature of art and perception, I said, "Actually we have someone here who took him up on the offer," whereupon I invited Longo to come up and tell his story.

Longo approached the podium shyly (somewhat surprisingly so in such a hip, seemingly self-assured, almost macho fellow) and launched into his tale about how in those days he'd been a graduate art student at Buffalo State College (later SUNY Buffalo), experimenting in all sorts of directions, and how people there kept telling him how his efforts reminded them of Bruce Nauman (whose work he knew) and Robert Irwin (whose work he really didn’t much—not surprisingly, since in those days Irwin was forbidding the photographic reproduction of his pieces on the grounds that such reproduction would capture everything that the work was not about, which is to say image, and nothing that it was about, which is to say presence, such that hardly anyone had actually seen much of his actual production). Anyway, Longo continued, he'd read how Irwin was going to be having this show down in the city and he wrote the veteran artist to ask if he might come down to meet him and perhaps help with the installation, and Irwin wrote back, "Sure," which is how it came to pass, Longo now related, that he and his then-girlfriend Cindy Sherman piled into a van one morning and headed east—but that the van stalled out a few dozen miles outside of Buffalo and he'd had to phone Irwin to explain that he wasn't going to be able to make it after all.

Longo recalled how Irwin had told him not to worry, that sooner or later they’d meet up anyway. Which is how it came to pass, Longo went on—and suddenly his voice halted, catching everyone in the audience quite off guard, for presently he was almost sobbing at the memory—that just a few weeks later, there’d been a knock on the door, and this great artist Robert Irwin had traveled all the way up to his remote town, and now simply sauntered in and planted himself in the kitchen, speaking to him and his girlfriend, these two nobody graduate students (I'm paraphrasing here), for five hours straight, at which point he, Longo, asked Irwin whether he would mind if he asked some fellow students to come join them—and that Irwin then stayed on for two whole days, simply engaging all of them in some of the most profoundly energizing conversations they'd ever had, and how (Longo at length began to compose himself) it had been one of the signal events of his early life as an artist. At which point he went back and took his seat, and I continued on.

About two weeks after my event, Irwin himself (then well into his eighties) was there on the same basement stage, before an audience including many of the same folks who had been at my talk (and a whole lot of others), engaging the current show's curator, Donna De Salvo, in vivid conversation. And at one point, their dialogue turned to his own early days as an artist, affiliated with the seminal Ferus Gallery, back in LA, and how at one point there in the early sixties the gallery artists had contrived to bring over a show by a still relatively little-known Italian artist, Giorgio Morandi (the Bolognese master who would soon become world-renowned for his endless renditions of deceptively simple groupings of bottles and pitchers and jars spread across his studio table).

Irwin described how he’d spent the better part of every single day at the gallery the entire time the show was up. The thing is, Irwin went on to explain—and now suddenly his voice was breaking, likewise catching all of us in the audience by surprise, and now, he, too, was almost sobbing—the guy was a true genius, and the experience of getting to spend all those days with those paintings (because they weren't just endless depictions of bottles and pitchers and jars; far from it, they were in fact all about light and structure and space and weight and lightness, deep inquiries into perception and presence, and in fact, Irwin now insisted, paradoxically, the only successful abstract expressionist paintings ever created by a European), the experience of being able to spend all that time in their presence (Irwin now began to steady himself, dabbing the tears from his eyes—he was sorry, he said, but seeing somebody just commit himself across an entire life like that, the grandeur of that achievement, it just got to him sometimes), was one of the most thrilling and formative in his entire life.

Which in turn got me recalling a moment several years earlier when I’d been visiting the magnificent Morandi retrospective at the Metropolitan for the umpteenth time that month and was standing before one of those ineffable bottle-and-pitcher-and-jar-marvels, when one of the fellows of the Institute I was directing in those days, the eminent New York graphic designer Milton Glaser (creator of the “I ♥️ NY” campaign and that indelible Bob Dylan poster and so many other iconic images), came up to me from behind, tapped me on the shoulder, and took to informing me as to how he himself, years earlier, had in fact had the privilege of actually studying with Morandi back in Bologna! Well, you can imagine the stories, but one in particular came bubbling up to the surface of my memory as I sat there in the Whitney audience, how one day after class, he, Glaser, and “The Old Professor,” as he called him, had been rifling through various art books—books about Piero della Francesca, to be specific— and the old professor was endeavoring to make a point when his hand paused on a particular image (in my mind's eye, I picture student and professor alighting on The Nativity, or The Baptism, of , The Resurrection one of those, I can't remember if Glaser was specific about which one),

whereupon the old man took a deep breath and let out a long sigh, almost a sob. "Piero,” he pronounced, at length, "was such a good foot man.” Glaser recalled how he must have looked back at The Old Man, somewhat mystified, whereupon Morandi continued, by way of clarification, “The way the feet are always planted like that, so firmly, so exactingly, on the ground."

Of course, the little toes lined up like that again and again, are hardly just little toes. In fact, lined up like that

they resemble nothing perhaps so much as bottles and pitchers and jars arrayed along a worktable. And, for that matter, neither are those Morandian offerings simply bottles and pitchers and jars—all of them, all of them, being essays in solidity and grace, gravity and light.

What exactly am I getting at here? Maybe something about Piero to Morandi to Irwin to Longo, I suppose, or else regarding Otherwise Macho Art Guys Unexpectedly Sobbing—who knows—though, actually, I do know what I am coming to.

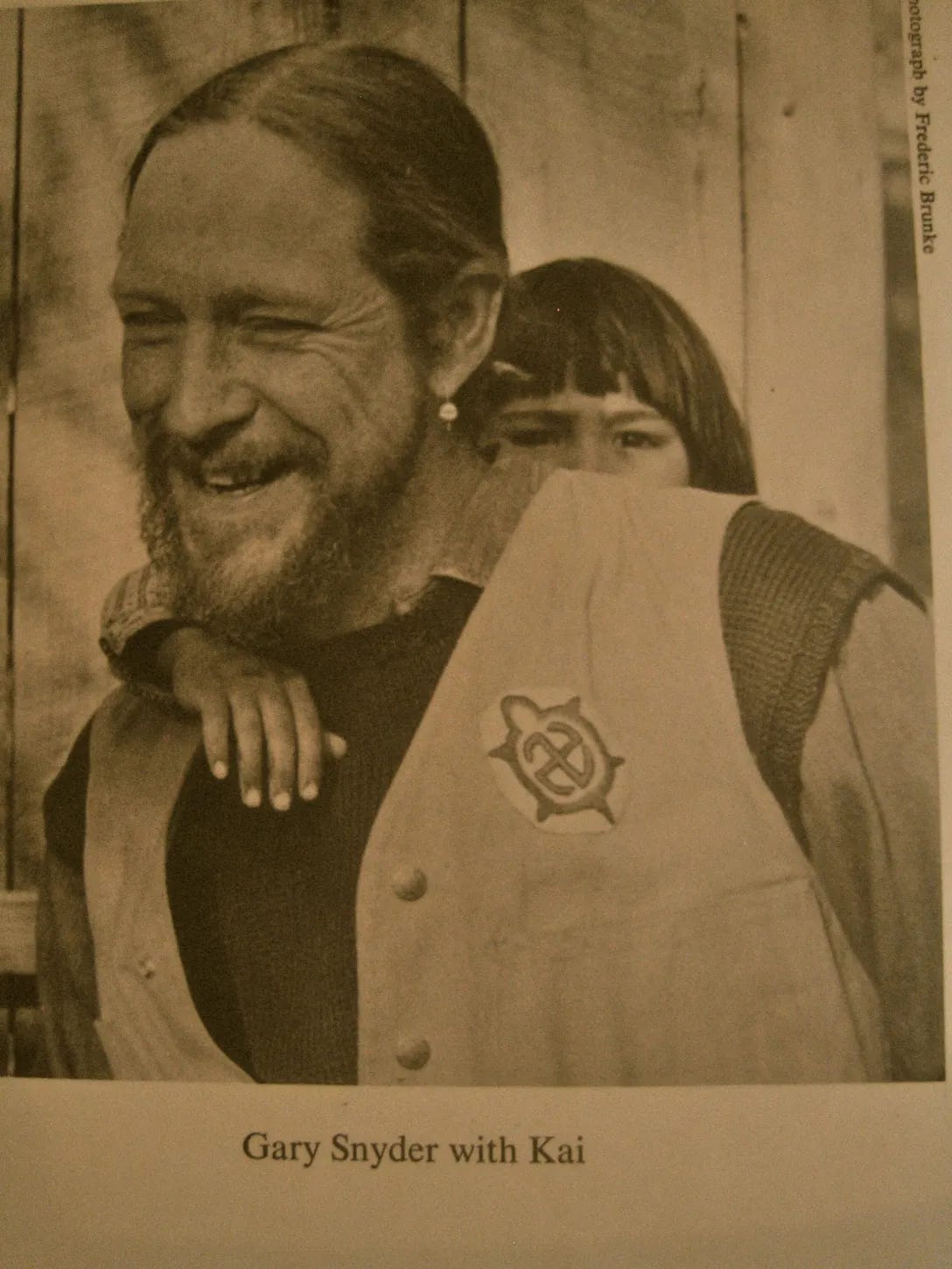

For I am coming to Gary Snyder, the great beat-adjacent and nature-tinged poet up there in his Sierra Nevada fastness, a poem of his I first encountered in my own student days, when it slew me to the core (and one that always seems to bring me up short, each time I read it aloud to my students, drawing forth a barely suppressed sob of my own). It's called "Axe Handles," and Snyder's evoking an incident one day when he was out back with his young son Kai:

One afternoon the last week in April

Showing Kai how to throw a hatchet

One-half turn and it sticks in a stump.

He recalls the hatchet-head

Without a handle, in the shop

And go-gets it, and wants it for his own.

A broken-off axe handle behind the door

Is long enough for a hatchet,

We cut it to length and take it

With the hatchet head

And working hatchet, to the wood block.

There I begin to shape the old handle

With the hatchet, and the phrase

First learned from Ezra Pound

Rings in my ears!

"When making an axe handle

the pattern is not far off."

And I say this to Kai

"Look: We'll shape the handle

By checking the handle

Of the axe we cut with–"

And he sees it. And I hear it again:

It's in Lu Ji's Wen Fu, fourth century

A.D. "Essay on Literature"—in the

Preface: "In making the handle

Of an axe

By cutting wood with an axe

The model is indeed near at hand."

My teacher Shih-hsiang Chen

Translated that and taught it years ago

And I see: Pound was an axe,

Chen was an axe, I am an axe

And my son a handle, soon

To be shaping again, model

And tool, craft of culture,

How we go on.

How we go on, indeed, across the endlessly self-generating, self-replicating flow of cultural transmission.

*

POSTSCRIPT

A few years after that 2013 Irwin opening and my subsequent piece in The Believer, I had occasion to meet Cindy Sherman at some sort of cocktail party (curiously, she is not that easy to recognize from her iconic work) and anyway, we got to talking and I mentioned her onetime partner Longo’s story about Bob Irwin’s surprise arrival at their doorstep back in Buffalo and the weekend he’d spent there engaging them and their friends in conversation about art, wondering if it had made a similar sort of impression on her. “Those guys,” she replied. “They just would not shut up! All night long, yakking and yakking away. I ended up retreating to my own room and closing the door.”

So, on the other hand, there’s that.

* * *

From the INDEX SPLENDORUM

Pavel Kogan’s ten-minute 1966 documentary rhapsode, Behold the Face, came into being near the end of the Khrushchev cultural thaw and remains one of the most enthralling studies ever committed to film on the enthrallment of art itself—in this case Leonardo’s Madonna Litta (The Nursing Madonna) in the collection of the Leningrad’s Hermitage museum, but even more so, the concentrated absorption evinced by the file of ordinary common folk successively coming under the painting’s spell.

Kogan, born in 1931 in Leningrad, a survivor of the city’s terrible siege (across which he lost a brother and both parents), became one of the leading figures (along with his wife Lyudmila Stanukinas—each having created over thirty films) in the Leningrad documentary film school, which in turn exercised a profound influence on such subsequent Soviet masters as Andrei Tarkovsky and Alexander Sakurov (whose monumental Russian Ark clearly owes the Kogan short a considerable debt).

There’s much more to say about Kogan (and we may return to him again in these pages in weeks to come), but for the time being, just watch the film…

…and perhaps emerge, like me, wondering what the hell has happened to the Russian people in the intervening 55 years since this film’s making, particularly across the last twenty of Putin’s ever more strangulating siege of a regime.

* * *

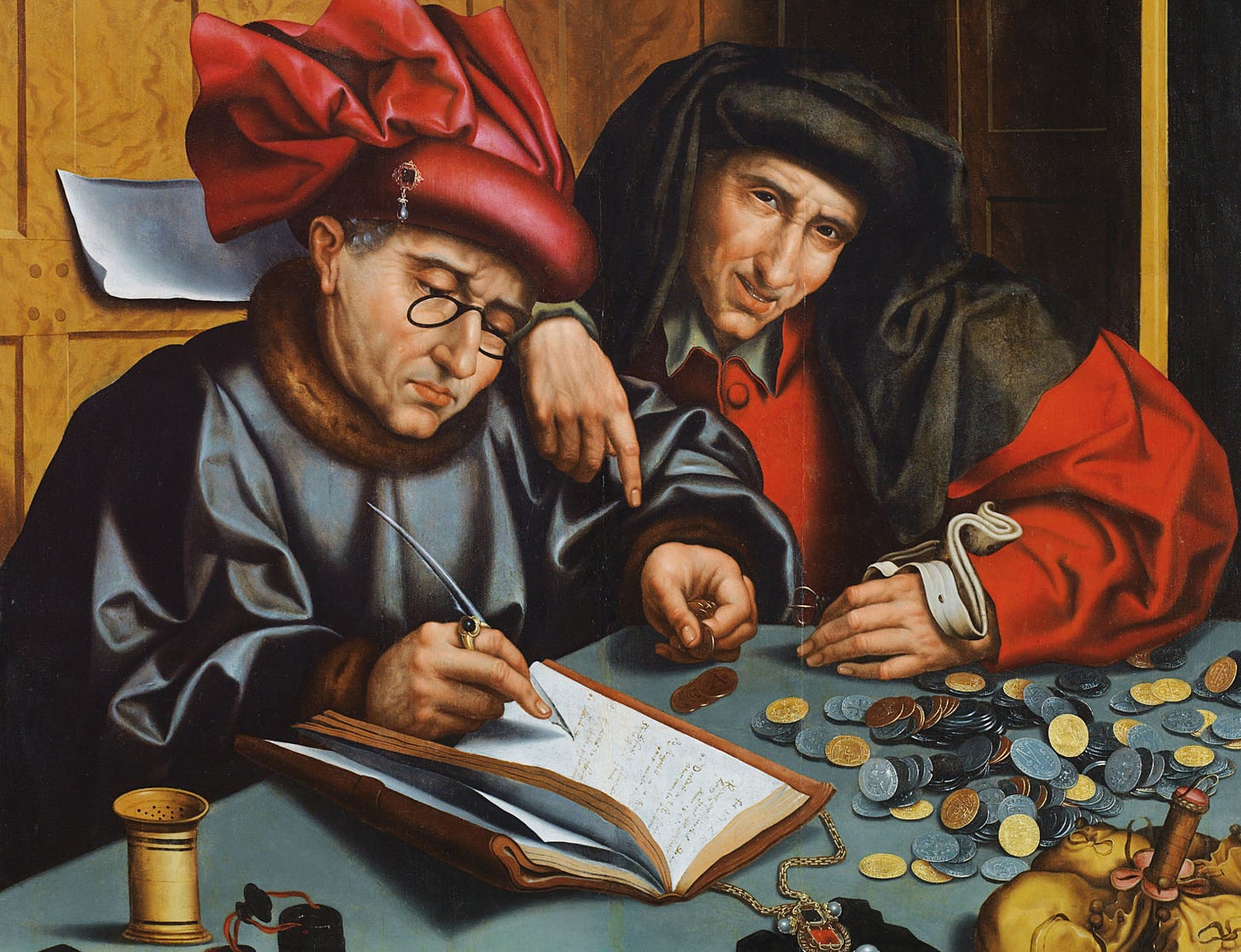

ARTWALK: The Giant at the Prado

So here’s a strikingly odd painting from the Prado. Attributed to a relatively minor master, Vincente Carducho (1576-1638), an Italian artist active in the royal court of Spain (who in his copious writings was disdainful of Velasquez’s exacting realism and Caravaggio’s ridiculous facility, going so far as to liken the latter to the AntiChrist), the 1635 painting has been relegated to one of the museum’s stairwells, off to the side. You could easily miss it except if you happened to notice it, after which it might prove hard to forget.

Because the thing of it is, the thing is downright huge. Here, maybe this will give you a better idea of its scale:

(Which is to say, almost 100 inches high and 80 wide.) And maybe I’m wrong but I can’t really think of single other old master facial portrait painting executed at such size (leaving aside the renditions of full bodies projected at great distances onto baroque ceilings and the like; I’m talking about framed portraits of individual heads). It’s reminiscent, I suppose, of the giant sculpted head of the Emperor Constantine (280-337 AD) in the Roman Forum…

…but that’s cheating, because for one thing that’s a sculpture, and for another, as can be seen above, it once graced the top of a colossal full body standing sculpture, now fallen to pieces (note the equally huge hands and elbows, etc., off to its side).

But the funny thing is that the museum folk at the Prado advance the kind-of silly suggestion that because of their thing’s egregious size, it may have been Carducho’s intent to portray “a giant, a figure taken from mythology in which such characters are described as being rough and primitive beings, possessed of remarkable strength and terrifying to look at.” Typical art-curator speak (except that, tellingly, the painting appears to have been displayed in the Buen Retiro palace along a staircase “known as the ‘buffoon’s staircase’ as it was hung with Velasquez’s famous paintings on that subject”—which is to say his dwarfs—“executed close to the date of this head”). (Good thing Carducho didn’t live to see that, as he died only three years after completing the painting—or, who knows, maybe the insult of being freakishly placed like that in his rival’s company is what killed him.)

Except that looking at the painting itself, there’s nothing in the face that really suggests that it is the portrait of a giant (there is or ought be, after all, a difference between a giant portrait of a regular face and a regular portrait of a giant’s face). And indeed, nowadays, we are used to seeing such giant portraits of everyday people’s faces by contemporary artists, as for instance,

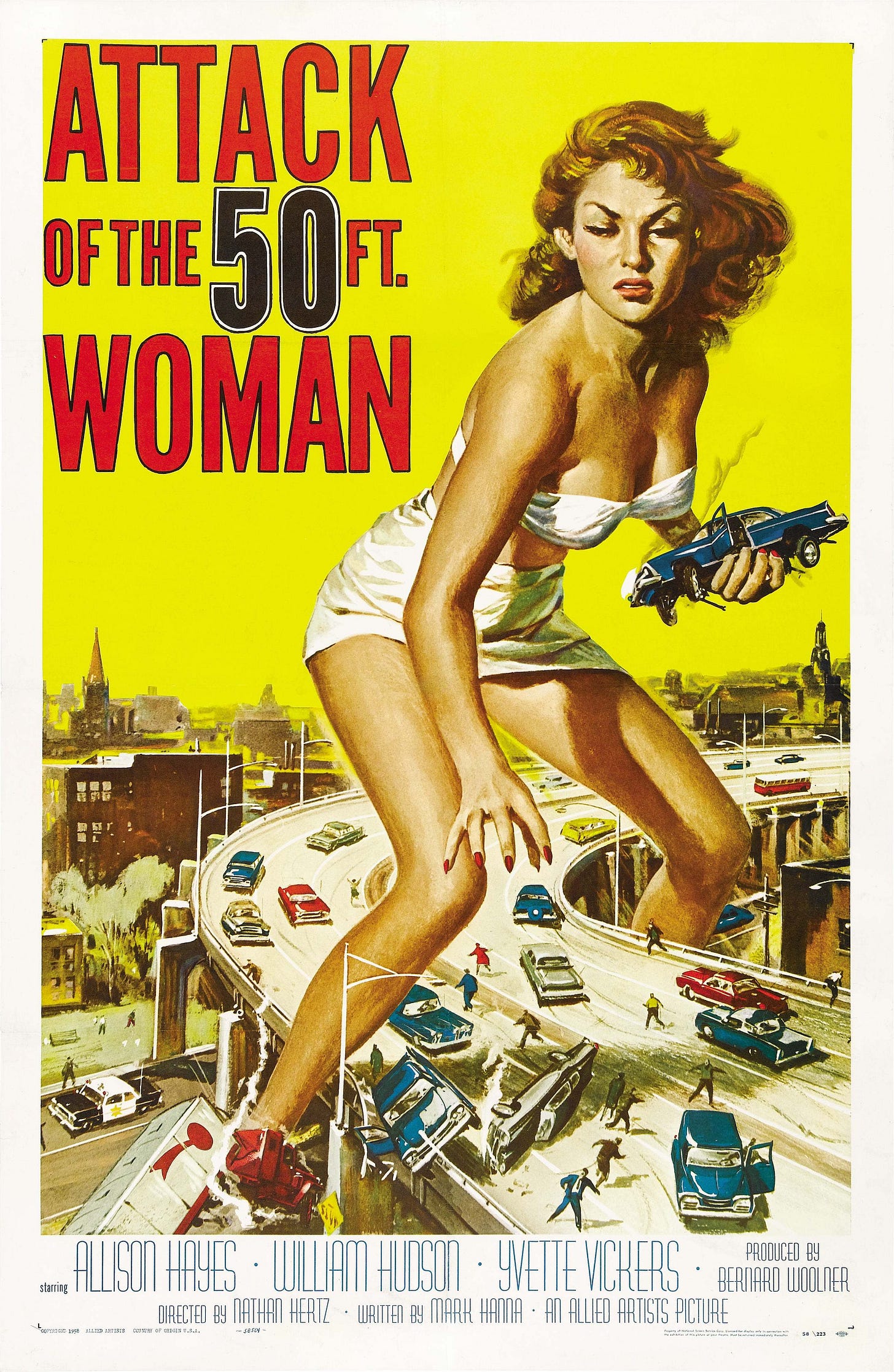

without necessarily imagining that the heads in question belong to actual fifty-foot tall giants.

On the contrary—and as it happens, notwithstanding the legendary film poster above, the Prado’s own collection may include this instance’s most famous example, certainly among old masters—if you want to imply the presence of a giant, you have, precisely, to include wee humans, just to give a sense of scale, as Goya himself did in his own iconic Colossus,

—a terrifying painting which, incidentally, is only 46 by 41 inches. And which, incidentally, I noticed on this most recent visit of mine to the Prado, has been reattributed to Goya’s friend and occasional collaborator Ascensio Julia.

Talk about relegation! A giant portrayed by a giant, being reduced to a giant portrayed by, well, a mere mortal.

Then again, there’s this:

The Prussian master Adolphe Menzel’s 1876 portrait of his own foot (at the Staatliche Museum in Berlin), only slightly larger than life size. But then again, Menzel was himself fairly diminutive, standing at only a Lautrecian four-feet, seven-inches. Which is to say that in this instance, while we may be looking at the foot of a dwarf, somehow it evinces the toe of a giant.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

Animal Mitchell website.

* * *

AS PROMISED

THE IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT

Though first, a throat-clearing observation:

I sometimes think that my dear wingman David Stanford may be throwing a bit of editorial shade my way with the cartoons he selects for each fresh issue of this Substack venture—”Ah, he ain’t so tough,” in the current instance, or “scrambled eggs” for brains a couple issues back (and I assure you that taunt was aimed at me and not, as it might coincidentally have seemed, at Robert Irwin). And then, too, last issue, when David had his Covid-masked lady finally telling her Covid-masked waiter “When,” after he’s poured her seven glasses of wine: surely that line harbored a veiled commentary on the conclusion of what may have grown to seem like the endless five-part cavalcade of my “All That is Solid” series (Enough already!)—doncha think?

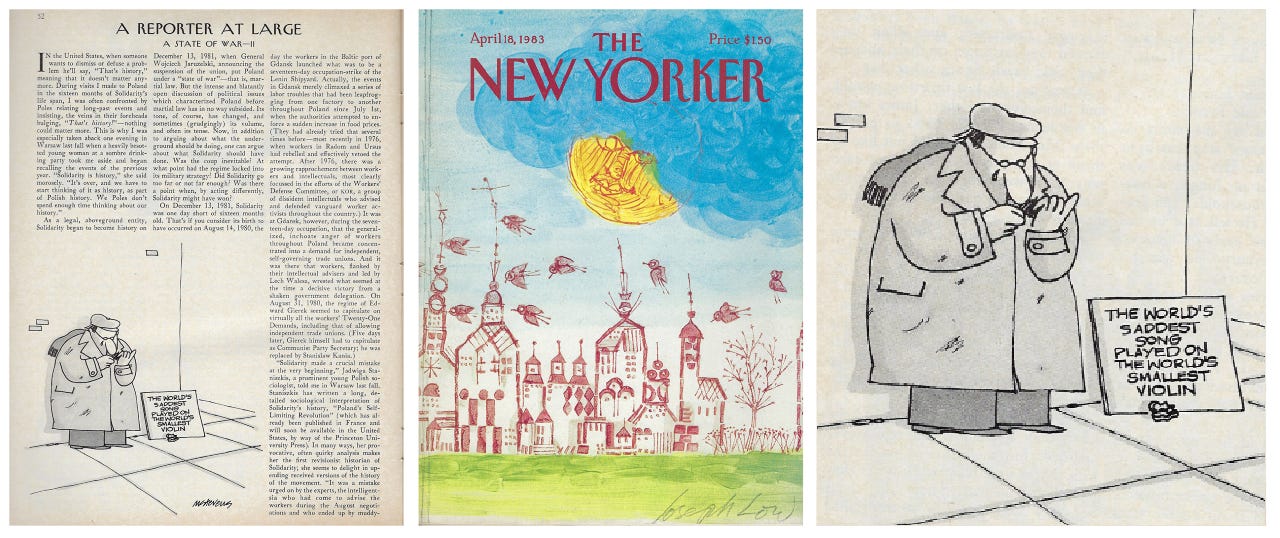

All of which reminds me of the time the cartoon gods at the New Yorker “accidentally” managed to feather a similar sort of commentary onto the first page of Part Two of my reportage on the imposition of martial law in Poland:

The world’s saddest song on the world’s tiniest violin, indeed. You talking to me, I couldn’t help but wonder at the time. You talking to me?

Still and all, this may indeed be the moment WHEN—that having been David’s nudging purport all along. The moment, that is, when we really need to talk about the future prospects of this entire Wondercabinet project.

Because, seriously, we can’t go on meeting like this.

SO, NOW FOR THE PITCH ITSELF!

We've been unfurling this whole Wondercabinet series for over six months now, and I’ve been feeling blessed to have this new outlet for thinking the way I think, in public, and sharing my discoveries and observations with you, my fellow world-marvellers. Part of me firmly believes that culture longs to be free, but my wingman David and I are both freelance whatever-we-ares, and are going to need to ask for your financial assistance if we’re going to be able to continue this whatever-It-is.

We share the premise of Substack—that writing is work like any other, and deserves to be compensated as such. On the other hand, I am loath to put the enterprise behind any sort of mandatory paywall, and prefer to ask for your voluntary as-you-can assistance.

Please click the Subscribe button below, even if you are already "subscribers" (this being a quirky Substack thing), and help us continue this venture. The good folks at Substack have helped us come up with four options.

Continue to receive for free: $0

Monthly subscription: $6

Annual subscription: $60

Very generous custom-amount subscription: $???!

You’ll note that with regard to that last, Substack requires a specific Founding Member’s subscription amount, and suggested we say $250. If you can’t quite reach that amount but still want to contribute more than the $60 level, just fill in your own figure. Likewise (pray!) with those of you who can contribute more. Substack lists all such figures as “annual” subscription fees, but of course you are always free to reconfigure that level (all the way down to zero if it comes to that) next year. So don’t let that spook you.

Those of you who literally can't pay don't have to: Stay with us. Those who can contribute more generously will help subsidize the participation of those who can't. And those who really want to give us a shot of "Hell yes you can!" (that, incidentally, is David talking) will inspire us immensely.

Incidentally, there’s one other way all of you can contribute to our shared enterprise, no matter your financial circumstances—and this is very important. If you’ve been enjoying these offerings and know of others who might, please spread the word as widely as you can. It’s easy, just hit the share button and enter your friends’ email addresses.

Right now, fewer than 4,000 of you receive our fortnightly, and even though we continue to enjoy exceptionally high levels of individual-issue engagement, as the folks at Substack have been informing us, we won’t be able to make a go of this thing in the long run without substantially expanding our base.

Pfew. Okay, we’ve said it. In exchange for all of that, please know that David and I have all sorts of fresh innovations planned for the months ahead—starting with the relaunch of my good old Convergence Contest (from back in my McSweeneys days) in which all of you will be invited to submit odd convergent instances of your own, opening them to wider community discussion. (Stay tuned for details in the weeks ahead).

That's it: thank you for giving all this your kind attention. As ever, your feedback and comments (Weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com) are always thoroughly welcome. Party on!

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

The first in a multi-part conversation with Blaise Aguera y Arcas, a big-deal research honcho at Google, one of my dearest friends notwithstanding our deep disagreements on truly fundamental matters regarding the moral and ontological status of bots, machine intelligence, and the like, regarding disconcertingly surging developments in that field; a close look at another astonishing painting by Adolphe Menzel, the little man with that giant toe from earlier in this issue; and more!

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Happy memories of going over and over again to a Morandi show in SF and nearly being mobbed by drunken Santas.

Ren, I have problems with the payment app... as usual, it is not world-friendly. This time I was stopped by the zip code... Norwegian zip code is not recognised. Any suggestions? I can't pay much, but I do agree, your and David's work so does deserve compensation. Really enjoyed this issue... Morandi is a love of mine. Thanks for your angle! pat coughlin