May 11, 2023 : Issue #42

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

This week, a pair of flashbacks. A climate-change one-act play Ren commissioned from Jon Robin Baitz back in 2006 as part of a festival of such fare he was curating that year in Chicago. And then, the late Harold Shapinsky, the subject of one of Ren’s first tragicomic passion pieces in the New Yorker, back in 1985, has a show up currently in New York.

* * *

The Main Event

"Shuddering to think"

A one-act climate-change play

by Jon Robin Baitz (2007)

Back in 2005, when Ren was already serving as the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU, he was invited to take on a concurrent role as artistic director of the Chicago Humanities Festival, the ongoing community-wide initiative consisting of upwards of one hundred events (panels, lectures, recitals, art shows, theater pieces and so forth) all grouped around a single annual theme, spread over the first two weeks of each November in venues throughout the windy city. He agreed to do so on condition that he could program his own first festival, in 2007, around the theme of climate change (this was in the days immediately before Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth film). And as part of that initiative, he commissioned a medley of “Acts of Concern,” a series that would come to comprise nine original one-act plays around themes of environmental urgency, by such authors as Sarah Ruhl, José Rivera, Tanya Saracho, Lisa Kron, and Don DeLillo, all of which would receive world-premiere readings at such venues as the Steppenwolf and Goodman theaters, among several others.

Ren’s longtime friend from his LA days, Jon Robin Baitz (LA-born but raised in Brazil and South Africa and the playwright behind such early celebrated hits as The Film Society and The Substance of Fire, going on from there from strength to strength both on and off Broadway and in films and television back in LA) was among the first cohort of invitees Ren contacted, but Baitz proved so extravagantly conflicted and dilatory that he missed the first Chicago cut; still, Ren kept nagging at him and he finally delivered a marvelously dark and comic meta effort just in time for the series’s reprise in New York. Which we in turn reprise here in the Wondercabinet: as will be seen, Baitz was not without his own options in turning Ren’s persistent siege back on itself:

SHUDDERING TO THINK

by Jon Robin Baitz (2007)

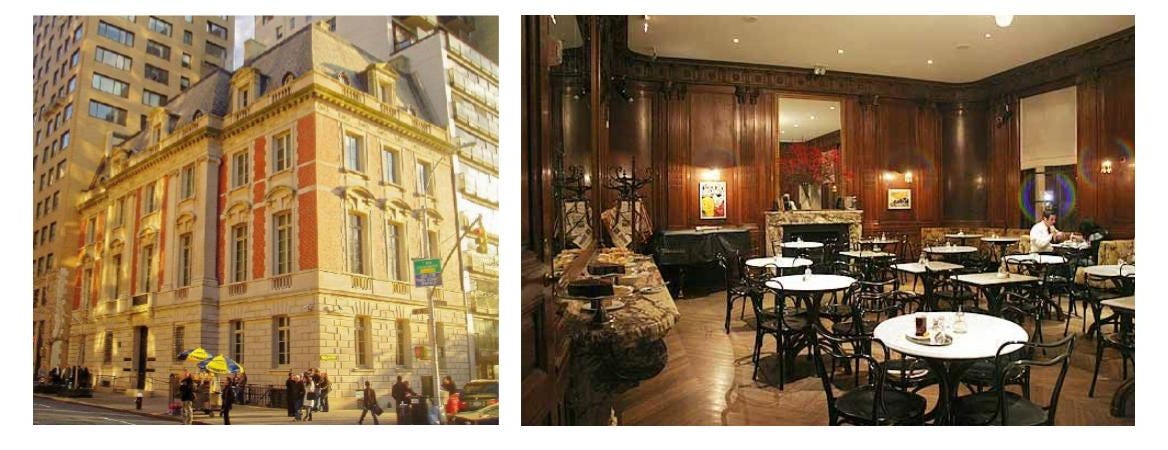

(Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder full blast. And then out as bright lights suddenly up on -- A tight little table at Café Sabarsky at the Neue Gallerie on the Upper East Side.

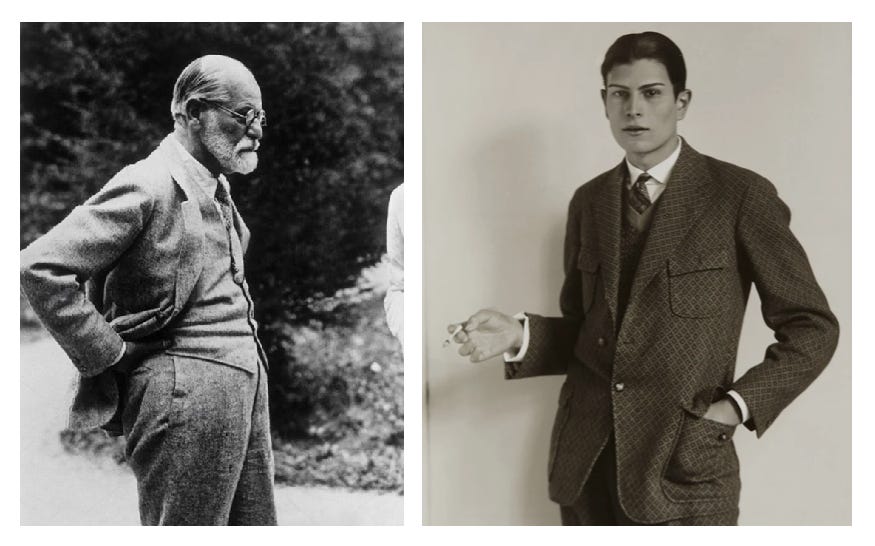

ROBBIE is in his thirties and absurdly handsome. Wears a tight, black suit, white shirt, skinny black tie, black glasses, giving him the look of someone perfectly at home in the Vienna Succession.

He is with his friend, REN. Short for LAWRENCE, also a writer, bearded and Freud-like, in his late sixties, also in suit and tie, something tweedy, and elegantly tailored. Both are taking off coats as we come up on them.

REN (brushing snow off)

So odd to have snow this late.

ROBBIE (also dusting snow off)

Sometimes that happens... a little late thing in the middle of Spring—

(They both sit.)

REN

Anyway, you were saying—you suddenly have some problem with this Earth Day thing?

ROBBIE (scoffing)

Oh please: Earth Day. It’s so inelegant. So Birkenstock-ish. So Woodstock. So poseury. We find one day to worship, but every other day of the year is spent blithely—you know—refuting that. It’s so human. So weak. It’s exactly like all of our uses for religion; we have for instance, Ren, Yom Kippur, a day of so called atonement—or the poor sex-addled Catholics have their confession. It’s like going to the gas station for those people, honestly. Right? But what comes next? Chaos. Rage.

REN (Beat, sighs, shakes his head, makes a little “OY” sound at Robbie, who is annoying him, and looks at the menu.)

I came here to get your play, not to have a symposium—

ROBBIE (interrupts, looking around)

God, I so very much love this place, The Neue Gallerie—I love Viennese food. And then upstairs there is Klimt and Egon Schiele, all the tortured, all the most wrenching pained, miserable and exacting artists—it just it gives you such an appetite.

REN

So you’re saying there’s no play?

ROBBIE (Reading the menu, scoffs again, a little French scoffing sound. )

“Earth Day”? We have these little affirmations of goodness, and of connectivity, of meaning, of our intentions to live responsible and fully connective lives—and then we use the old bombs, or we re-elect the old murderers...we might again this season, McCain seriously proposes being in Iraq for a thousand years—

(Beat—stops)

Huh. Look at that. I love this place. I’m thinking of the avocado salad with crab meat and tomatoes or the scallops with green asparagus, lemon vinaigrette and basil oil, you?

REN (menu glance)

The goulash and the smoked trout salad thing...

(He looks at Robbie.)

Okay. Spill it. So this lunch, right—just lay it on me—okay…? This is—this is the lunch where you bullshit me, Robbie, and tell me that after you promised to write a play for this, you promised me—

ROBBIE

I did not promise—

REN

—you at the last moment decided not to do it? And I—what am I supposed to do—have an empty stage where your play was gonna go —is that it? I have an evening to produce, I have—this matters to me—this is important to me, I’m not as blasé as you, I—

ROBBIE

Plays for Earth Day, Ren? This is so childish. These agit-prop theatre things. Preach to the choir, and then go to the pub afterwards, it’s sooooooo anemic, so insufficient... They have great deviled eggs here. On toast. With some—

REN (over him)

You’re so negative, what happened to you? Is this what TV has done to you?

ROBBIE

Hey, can I tell you something: You know what you are?

(Beat)

You are—an enthusiast.

REN (smiling)

No, I am not an enthusiast. How dare you!

(Beat)

I prefer to think of myself as a despairing optimist.

ROBBIE

In other words, an enthusiast! I don’t care for enthusiasts, Ren. Enthusiasts get us into wars. Enthusiasts hop everyone up. Enthusiasts don’t have to stay up all night working; they just have to enthuse all over the place, dripping excitement, and entrap people into their—

REN (over him)

Jesus, Robbie. This is—let me try and explain this to you once again. Scientists and politicians have totally and utterly failed in warning—in waking people up from sleepwalking. This crisis is not just an ecological one but also a crisis of vision! Vision—which is the purview of artists—of playwrights—and THAT’S why I wanted YOU!

(Beat)

ROBBIE

You know, you’ve done this before. You’re always, you pop up, Ren, and try and lure me into these—actually—you know, physically rather dangerous endeavors—

REN

Oh my God, what are you talking about? “Physically dangerous???”

(A handsome waiter comes by, longish hair. He is in his twenties, full of life, and charm and youth.)

NIC

Gentlemen, my name is Nic, and I just wanted to tell you, it seems—weirdly—we’re going to be closing an hour early today. There apparently is a like—total killer like— blizzard on the way, they’re predicting forty-six inches of snow dumped on the whole Eastern Seaboard within the next few hours. I guess. Like.

REN

Forty-six? Inches...?

NIC

Or like maybe sixty or whatever. So if I could take your... order, that gives you twenty minutes or so to eat, which should be enough because the portions are really rather small.

(Ren and Robbie stare at the waiter.)

I have to get back to Red Hook, so... I mean. I should probably just cut out. You have to walk blocks to get to my place… Most of the staff has like blown outta here. They had the like mayor and the governor you know—doing “don’t panic, don’t panic” whatever.

ROBBIE

It’s April. It’s late April, there aren’t blizzards in—forty-six or sixty inches of snow? What is that? Where are we, Iceland? I’ll have the scallops. Please.

REN

And I’d like the trout...? And a glass of Riesling.

ROBBIE

Me too please, Nic.

NIC

Great.

ROBBIE

Great.

NIC

(Nic nods and goes off.)

REN

What did you mean about “physically dangerous proposals...?”

ROBBIE (outraged)

Do you not remember? Come on, Ren. You tried to get me to write a play for no good reason, no good reason, after September 11, about—about—it opened with a big giant fucking bang, Ren, and there’s a fucking suicide bomber standing there—smoking —smoke coming off him!

Grinning little Arab kid. And one by one, one by one—like seventy-six virgins—offer themselves up, do you remember this??

REN

It was a great idea! You should write it! Unlimited sex with 72 virgins in heaven. Not 76; that would be insane—

ROBBIE

And he—the cute little theatrical suicide bomber—gets completely exhausted from the madness of having to fornicate with seventy-two virgins, one after another, and suffering from sex fatigue, at like number twenty—he looks up to the heavens and says “Look, I’m really tired, this may be heaven but...”

REN (calmly)

Let me restate my idea for you, Robbie. Because that wasn’t it at all. He wasn’t exhausted from fornication. He was exhausted from the presence of the seventy-two virgins—in other words, seventy-two actual teeny-boppers, toenail-painting, endlessly gossipy, blithely backstabbing, mindlessly consumerist mall rats—and then by the end of the first act, Robbie, he finally manages to bed one. And at the opening of Act Two, she’s a virgin all over again, and he looks up to the heavens and says “I know this is paradise, but I’m so tired...” And a booming Allah-like voice says “What makes you think this is paradise?”

ROBBIE (after a pause)

And that play wouldn’t get me killed in the streets, Ren?

REN (delighted)

Oh it probably would. Yes.

ROBBIE

I mean, probably Salman Rushdie had some friend like you egging him on; “Oh the Satanic Verses is a great idea for a book. Go Salman, go!!!!” Jesus. Maybe it was you. You know him, don’t you? Maybe you have this plan to kill all the other writers, or something sick?

REN

This has nothing to do with you not writing a play for Earth Day.

(Nic, looking sheepish, is back.)

NIC

Sorry. Uhm... there’s a Sancerre—the Riesling—you know—we I guess ran out of it. And frankly—the weather has been so fucked in the Rhine region, according to our wine guy, or whatever, it sorta sucked, our wine guy said that the wines are all gonna start sucking.

ROBBIE

Thanks, whatever... anything...

(Nic heads off quietly. Bitter, Robbie goes on.)

I never said I didn’t write a play for you, did I? God. I just said that you’re always trying to get me to do terrible things and I want to know why? And now there’s gonna be a blizzard and we’re stuck here. On the Upper East Side, I’d rather be stuck in Romania. These people with stretched faces. That’s what the world is, nobody cares about Earth Day—they care about their plastic surgeon.

NIC (reappearing)

Bad news. It seems that there’s a—some people who had the scallops sent them back—it’s really hard with the seafood lately, you just don’t know what you’re gonna get... Which leads me to the smoked trout.

(Shakes his head. A whisper.)

Why don’t you try the spicy egg spread and goulash instead.

ROBBIE

Wow. Uh. Okay. Yeah, sure. Why?

NIC

There’s a warning notice about the trout farm, apparently someone accidentally dumped like, I don’t know, Benzedrine or benzol—in the entire water supply or whatever in Maine or Nova Scotia where the like farm is—we just got a fax from them —also P.S.—The chef wants to cut out, before the weather gets really bad—I just looked out, its coming down pretty hard, so the egg is—it’s already made, have the spicy egg—it’ll be a lot easier on everyone.

ROBBIE

...You don’t really want to be here, do you, Nic?

NIC

Not so much... I sorta like the art, but serving sucks.

(He retreats.)

REN

This is a nightmare. Pure and simple. A nightmare.

ROBBIE

It’s my fault for saying yes to you. For agreeing. But the truth is, I don’t really, I just I can’t think about anything other than this election and getting these terrible disgusting criminals... out. And all I can think about is the alternative to the Clintons who pardoned Marc Rich in return for—

REN (angry, over him)

Why did you even agree to do it? I mean—I do not want to discuss the election, I am SICK of the election. I just want to know why you waited so long to tell me you had nothing to say about Earth Day.

(Pause. Robbie nods. Butters his bread, shaking his head, thinking.)

ROBBIE

You have no idea what my life is like. You know, I’m so reclusive and desperate—or—I just—I thought there might be like a nice dinner with all the other playwrights, you know, suddenly it’s Sondheim and David Hare and—and Sam Shepard and—

REN

They’re not doing it! Who said anything about David Hare, are you nuts?

ROBBIE

That’s right; of course they’re not doing it, I’m sure you fucking bugged them too, but they’re too smart.

(Beat. Sad.)

I thought I should do it, I’ve been—you know, I was in LA for a while and I haven’t really had anything on the boards for a while I thought there’d be a thing where we all—had meals and hung out and... it’s so pathetic.

REN

There will be a dinner, there’s always a dinner. And why did you write in the—

(He takes a script out and looks at it.)

Why did you write in the stage directions “Robbie is in his thirties and absurdly handsome”???? And that I’m in my late sixties??? Why?

ROBBIE (laughing)

Is that what’s bothering you? It was a joke, come on. But I’m not—I’m not an unattractive—I mean, we can’t exactly ask Nathan to play me, can we? Look, let’s—you don’t want to be totally unbelievable—and I mean, you know, you have an older quality that—

REN (shouting, outraged)

You’re forty-fucking-six, less than ten years younger than me, and you’ve been playing an off-Broadway enfant terrible since I met you in 1986, but in fact you’re an old, old man inside!

ROBBIE

You’re just furious that I didn’t describe you as absurdly handsome, at least I gave you “an expensive well-tailored suit and a Freud-like aspect”!

REN

I do not have a “Freud-like Aspect.” GOD! And the goddamn actor playing you is a lot better looking than you are, let me tell you!!'

ROBBIE (bitterly)

Well ditto my literary friend, dit-fucking-o, mi amigo!

REN

You’re sharing a bill with Sarah Ruhl and Lisa Krohn. I mean, is that not good enough for you, you miserable little shit?

(silence)

ROBBIE (petulant)

Well, I like them both a lot, an awful lot, they’re terrific, God knows, but they’re no Stephen Sondheim, I am willing to swear you promised Sondheim was gonna write a ballad for Earth Day.

REN

A BALLAD for EARTH DAY???? FROM SONDHEIM ???!!!! What would that even BE???? Everyone dying and sobbing? Dripping with mordant ironies????

(Beat)

I shudder to think. Hey—that’s a good title for a play, you wanna use it? Or a book of essays.

ROBBIE

A book of essays? Who do you think I am—Edmund Wilson or Nora Ephron?—I’m not an essayist. I’m a show-offy little trickster of a hack!! I have no right to—I’m a fraud, not an essayist, and the best place for a fraud is the theatre!

REN (mildly, shrugging)

Those Huffington pieces you do are actually pretty good.

ROBBIE

I hate that place, it’s like a fucking disgusting dinner party in the Hollywood Hills, God, all those opinionizing monsters shouting to be heard, and to see how many comments they get—ugh—God, all that show-offy blathering—of the bloggers—the high self regard—I know, because I’m one of them. I’m the biggest show-off of them all.

(Beat, an off-handed throwaway)

And who is this DeLillo fellow? Never heard of him.

(scoffing)

Don DeLillo. Please.

(shaking his head, as Ren stares)

No, Ren. No—enough egocentric little—

REN (looks out at the audience, points)

You don’t think what you’re doing right now is egocentric?

Have you had a breakdown? Have you? This is sickening, just—to see you devolve into this... pool of self-referential mulch. Robbie, Robbie, Robbie—you’re breaking my heart here.

ROBBIE (calm)

Yes. I have. I have had a GIANT MASSIVE unmitigated full blown Bloomsbury-sized fucking breakdown. The kind the artists they show in this building had. I have had a breakdown of all the connective tissue of bullshit and posing and politics and horseshit, I just wanna make people laugh, is that so bad? Huh? Huh? Why is that a crime? I want to live the rest of my days tsuris-free, crusade-free, word-and-thought-free in a miasma of lassitude and bullshit, JUST LIKE THE REST OF THE WORLD DOES....

(Robbie lights a cigarette.)

REN (not unkindly)

Honey. Look. You can’t smoke in here. I know some very good Polish shrinks up in Rye, they work with shamanistic stuff and twigs and rituals—they could really—

ROBBIE (over him)

There’s about to be an Icelandic fucking snowstorm out there, Ren. I don’t care anymore. In late April. It’s virtually May. What does it matter if I smoke or not? It’s the end of the world. It’s the end of the world. We’ve tipped over. The thing is unstoppable.

REN

Climate change? Of course it is stoppable.

ROBBIE (screaming, standing)

By plays??? By PLAYS?????? You think the theatre has even a scintilla of influence on anything right now? Except little gay kids across the land? The theatre is about as effective as—you wanna know the only institution with less relevance to the populace today—the Democratic party—that’s who—the Dems—at affecting change; the two have been equally, you know, forceful and persuasive presences in American fucking life today... Christ.

(scorn)

The theatre. Please. Please. Please spare me the theatre.

(scorn)

This church. This church of bad ideas, alta-kakas, and moaning.

(Pause. Ren looks shocked. He’s thinking of leaving. He sits, breathing heavily.)

REN

I would like to leave but I can’t in good conscience leave you in this condition.

NIC (returning, a little worn)

Sorry guys. But... The wine guy—sigh—he just refused to serve the Sancerre... He said it’s “swill.”

REN

“Swill?” What’s happening? I feel like I’m having some sort of aneurysm. Am I pale?

NIC

He said that it’s an open secret amongst all the wine people that apparently global warming is totally fucking up the Loire and the Rhone wines,

and nobody really got hip to it until now. It’s a total bitch. We have some nice Pilsner.

(Beat, shy)

By the way, Mister Baitz, I enjoy your work.

REN (disgusted)

OH. MY. GOD. You’re just embarrassing yourself, Robbie. Why would you write a line that craven. I feel like I have ants crawling up my spine. God.

ROBBIE (to Nic, scoffing)

This guy here is trying to get me to write a short play for Earth Day. Can you believe it?

NIC (shrugs)

Dude. That’s cool. And I loved your book about David Hockney, Mr. Weschler. And the one about the old painter who was rediscovered.

REN

Thank you, Nic, but it’s a little late.

(to Robbie)

Why are you having him do this? It’s unseemly.

ROBBIE

But my point is—all I can do is give words to actors—I can’t do anything about the things that are going on. I can’t do anything about Darfur and Bush and I couldn’t do anything about Reagan or—

NIC

He’s right Mr. Weschler, with all due respect. I mean, if Robbie wants to let it all go, he should. I can’t see what good some plays are gonna—

ROBBIE (over him)

A beer is fine, Nic, bring yourself one. We’re the only people here, right?

NIC (exiting)

Only customers, yeah. Sure. I’ll be right back.

(Beat)

By the way, guys, I DO have my own opinions. Okay?

REN (sulky)

Well, I hope you’re happy. Now there’s no evening.

ROBBIE (calm)

Ren, Ren, Ren, Ren. Don’t you understand? “The Sancerre is swill.”

(quietly, passionate)

That says it all on every level. Do you know what’s happened to the—do you know what that says about the best wine growing region on the planet? A soil perfectly suited—to the creation of wine from the grape... chalky seams of soil running under the earth from the White Cliffs of Dover, and a climate that breathed just the right amount of sun, just the right chill on vines that provided monks with a purpose far greater than praying to a silent and vengeful god—has been compromised, breached, totalled... the Sancerre is SWILL means “WE ARE DONE.” La Guerre est fini.

(pause)

REN (a frustrated shrug)

You could have written to that.

(Sad. Pulls out a small phone book and looks up numbers.)

I guess I’ll call Rich Greenberg, he can pull something together really quickly. Guare... Wally...

ROBBIE (a total brat)

I have David Hare’s number, why don’t you call him?

REN

You know, my grandfather Ernst Toch wrote an opera just like this called Egon und Emilie. In Germany in 1927...

ROBBIE

Oh? Do tell.

(Bored. Head in his hands, miserable.)

REN

It opens as a good looking chic couple comes on stage and the woman begins crowing about how great it is to be singing like this and embarking on an opera. And she waits for her consort's riposte—which doesn't come. He’s totally silent, says nothing, just sits there reading a paper. She tries to rouse him: nada.

The more frantically she tries, the more frantic the music becomes—and still no dice. Finally she runs off-stage, a broken woman. And then the guy—twenty minutes into the piece, he gets up, clears his throat, and announces that he can't stand opera, he’s done with all the artifice and bullshit—he’s not gonna have any part in this nonsense any further. Curtain falls: end of opera, end of evening. As nutty as that opera may have seemed in Berlin in 1928, with the passing months it began to take on a—what shall we call it—a totally prophetic aura.

Like New York, this totally cosmopolitan city: Berlin was also filled with people who had no intention of indulging this nonsense (this marvelous cosmopolitan capital city with its top-notch orchestras, its three full-time opera houses, and its dozens upon dozens of theaters, all trafficking in the latest idioms) any further. And my grandfather’s little chamber opera offered a foreshadowing of the futility of art in the looming era of the Nazis—and—don’t you see, Robbie?—this play would be foreshadowing our new holocaust—the hopelessness and—inadequacy...

(The lights start to flicker. Ren and Robbie look around. On and off, a few times.)

ROBBIE (looking around)

Wow. Maybe the weather is doing something... funky to the—

REN

I hope my family is okay. I’m gonna try and call them.

(Beat. Through the following, he tries dialing his cell phone repeatedly.)

I don’t know what to say to you at this point. I’m tired. I’m a humanist. I’m a father, so proud of my daughter—that amazing girl who exudes excitement—I’m—a thinker, a guy, I love the world, I love to be part of the brighter energies of the world, of what’s good about the shock, the surprise, the new. I’ve spent my whole life as a writer celebrating those things, and in some ways I’m an innocent, yes, and fairly foolish. A despairing optimist. But this—this stasis and blockage of yours is simply— unacceptable. It’s not the way to go down, if you’re going down, JRB. Think about my daughter, your family, your friends—you can’t go down this way.

(The lights continue to flicker. Robbie lights the candle on the table, nodding, listening.)

ROBBIE (hands Ren his cell)

Having trouble getting a signal? Use mine...

REN

Thanks...

(He does so, continues trying to dial.)

I hate these things. They never work when you need them.

(Puts down cell. Beat.)

So... Say a bunch of writers come together to write about the decaying state of terra firma, the vast and unstoppable entropic pulls, the fires dying out on the sun, and the oceans dying, rising, choking on poisons; and say that a bunch of audiences come together to see their plays... these audiences. These audiences, they count. The scientists were inadequate to the task, but I wish you’d try.

ROBBIE (shaking his head)

It’s the last audience, Ren. The last audience. Because the audience is dying just like the earth.

These are the children of the—these aged and white audiences—these are the children of the men and women who went avidly to see Odets and Williams and Arthur... their parents went and took them... so they go—but their kids... don’t. It’s evolution. The theatre is doing what the Earth is, just a lot quicker.

(Beat)

I would have liked to have been around for those days.

(Beat. Lights flicker.)

It’s really cold in here, isn’t it?

REN (looking around)

Where is everybody?

ROBBIE

We’re the only ones here.

(Nic comes back on stage, wearing a snow-covered parka. He is caked in snow. He is shuddering, shaking, teeth chattering. He takes off his coat, scarf.)

NIC

Listen, everybody left. The whole building is empty—the whole place. It seems that the storm is—I just went outside—you should see—it’s all white.

It’s just total whiteness. Everywhere. I mean, the park is gone. The trees are gone. And you can’t tell where the sky ends and the city begins. It’s like—it’s like a nothingness. A giant nothingness. Nobody is on the street. No cabs. Nothing.

ROBBIE (after a moment)

You didn’t bring the beer?

NIC

I just had a really bad feeling, and left, I’m sorry. I’ll go get you some. I don’t know. It felt so total, out there. So... final. And I kept thinking about the Central Park Zoo. What’s going to happen to all those animals, those poor sweet animals.

The monkeys and the—maybe the polar bears will be okay. But what about everybody else. What about the...?

(Beat)

They’re so far from home, too. All those animals. Animals shouldn’t die in New York City. It’s not fucking right. I... I shudder to think... snow upon snow upon snow... They must be so cold... And think about what it’s gonna be like if it melts, when it melts—this city will be flooded. Underwater. It’ll be like Katrina. The poor animals. I don’t know. Maybe I’ll like go down there or whatever...

(He leaves. The lights flicker and flicker and flicker and are out. The only light now is the candle light. )

REN (rising, panic setting in)

Look. Look. I have to try and get home, I have to get back to Westchester... I have my car here. If you’re going... if either of you want a ride somewhere.

NIC

I don’t think you’re gonna be able to make it... They said the Henry Hudson Parkway is closed and—

REN (extremely upset)

We’re having a dinner party tonight. I have to be there. We’re having a dinner with a group of dissident Iranian film-makers. I’m making Goulash. Would you like to come? They’re a very interesting lot. They...

ROBBIE (admiring)

You never give up, do you? Such a humanist.

REN (wry)

As much as I can be, Robbie.

ROBBIE (quietly)

Good luck, Ren. Thanks for everything. I’m gonna wait it out. Maybe I’ll wander around the Gallery. Sit in front of the Klimts. So much wall power. SO much energy.

REN

You’re gonna stay here?

ROBBIE (sad, wistful, a small smile)

Maybe I’ll try and take some of the art to the top floor, in case there’s a flood. Take some of the Josef Hoffmanns and the Klimts and Beckmanns. The Kokoshkas. The Max Ernst I love. So much great stuff in this building... Don’t want them to get damaged do we? The human stuff... try and... you know...

REN

Bye, Robbie.

ROBBIE

Bye, Ren.

(Ren starts to exit.)

Ren—Happy Earth Day.

(Beat)

I hope it goes well. I hope it’s a success...

(Ren exits. Robbie sits. He lights another cigarette, the flash of the match is vivid, and the Mahler Kindertotenlieder is heard again as Robbie blows out the candle, and the only light is the small, burning, ochre ember from his cigarette.)

THE END

*

Anyone interested in mounting an actual production of Shuddering to Think should contact Mr. Baitz’s agent George Lane at Creative Artists Agency (GLane@caa.com or 212-277-9000).

Ourselves, we are thinking Harry Styles as ROBBIE and Wally Shawn as REN—or, better yet, the other way around!

* * *

ART WALK

I was puttering about the Lower East Side here in New York the other day, in the shadow of the New Museum, dipping into one gallery and then the next, when I happened to wander into the Howl Arts not-for-profit space at 250 Bowery on the second floor, where, to my astonishment, they’d mounted a fine surprisingly ambitious little show of the work of the late Harold Shapinsky. Astonishment because, for some reason, no one had bothered to tell me about it. But delighted satisfaction nonetheless, because Shapinsky had been the subject of “A Strange Destiny,” one of my first longform pieces of reportage at the New Yorker, back in the December 16, 1985 issue of the magazine. It had been the strange destiny of this completely bypassed first-generation abstract expressionist to have continued producing work of notable quality (almost completely unchanging over the decades, as fresh as in the years he’d begun) to virtually no recognition whatsoever, until, through a long loopy set of coincidences, he was suddenly discovered by an itinerant part-time teacher of rudimentary English at a community college in the (then) cow-town of Bangalore, India, name of Akumal Ramachander, who became convinced that it was his own destiny, his karma, as he called it, to reveal Shapinsky to the world, to bring him the success and fame that had thus far eluded him and in the process to bring all of India the honor of having recognized a genius who’d been entirely ignored by the top art historians, critics, and gallerists in the heart of the art world in New York City. And he kinda, sorta proceeded to do just that. You can, if you like, get a sense of the arc of the tale by sampling the first two pages of the New Yorker piece here (aye, and look at that quintessentially gentle-fierce cartoon of the consummately well-beloved Ed Koren’s there on the second page, Ed who himself only slipped away this past week, aye); and you can access the saga in its entirety as the first novella in my early Wanderer in the Perfect City collection of “passion pieces.” And, if you happen to live in New York, you can go see the show itself through Sunday, May 21. So do consider doing so.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

A bad day for a young composer. And all sorts of other goodies…

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the Complete Wondercabinet Archive.