WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME!

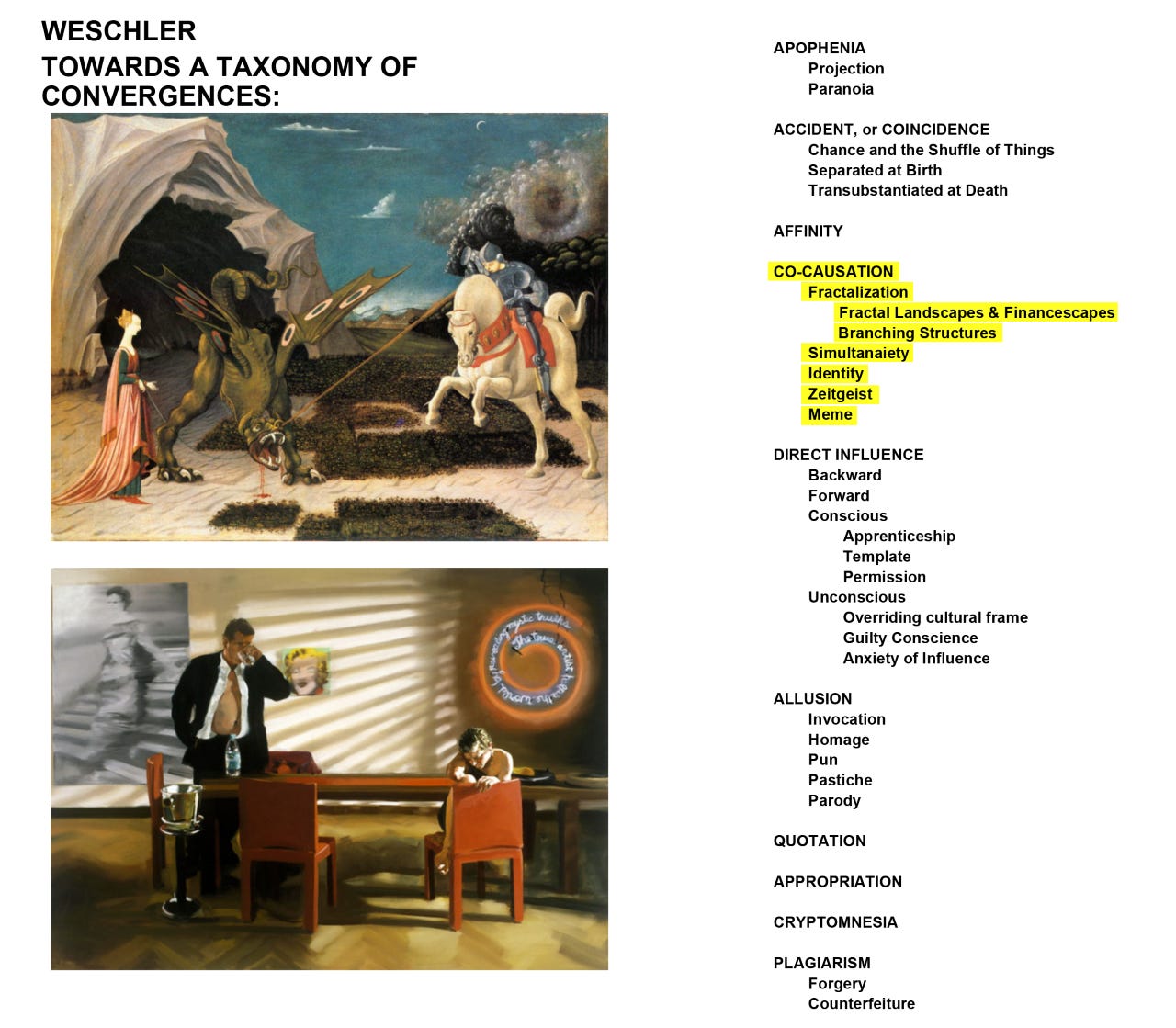

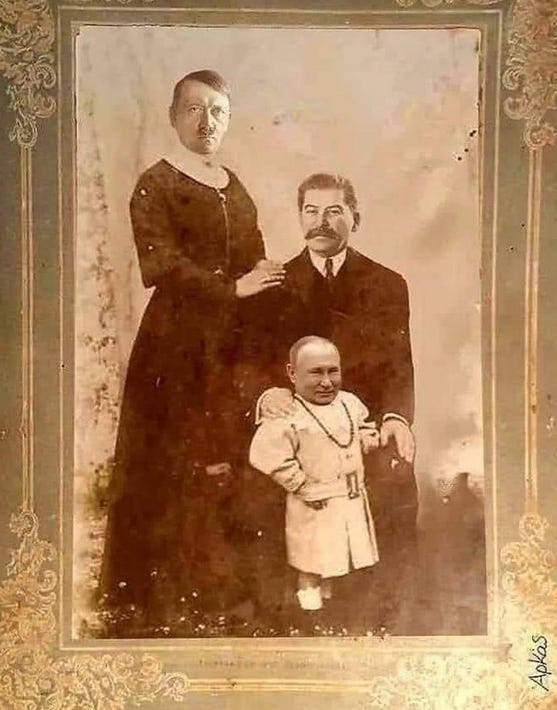

“Awwww, who’s this little fellow in his itty-bitty robe? Why, that’s tiny baby Vlady, the Stalins’ little boy!” (with apologies to Wisława Szymborska). And just look at those proudly beaming parents! All sorts of grim convergences caroming off that image, of which more below. First, though, we will be continuing our ongoing procession through a taxonomy of the convergent impulse itself, this being part three (the last two issues having covered the impulse behind the entire exercise, and then Apophenia, Projection, Paranoia, Accidental Coincidences, and Affinities). This time we’ll be considering instances where things or passages or images remind us of each other because in fact they share common causes or occasions. Following that, first an interlude in which we indeed dive deeper into the Baby Putin problem, before visiting (in the A-V ROOM) with Benjamin Labatut, the young Chilean author behind the extraordinary When We Cease to Understand the World, justifiably up for Book of the Year at the LA Times Book Festival (later this coming month). And finally, riffing off last issue’s Imaginary Object by Daniel Crooks, the INDEX SPLENDORUM will feature a real dazzler: ice crystalizing before our very eyes.

* * *

This Issue’s Main Event:

All That is Solid:

Toward a Taxonomy of Convergences & A Unified Field Theory of Cultural Transmission

PART THREE

Now, however, we move away from the terrain of inchoate projections, vague coincidences and misty affinities, into that part of the widening spectrum where if things happen to look alike, it’s because they’re likely to be drawing on the same sorts of sources. A whole virtual side-cabinet, that is, devoted to instances of

CO-CAUSATION

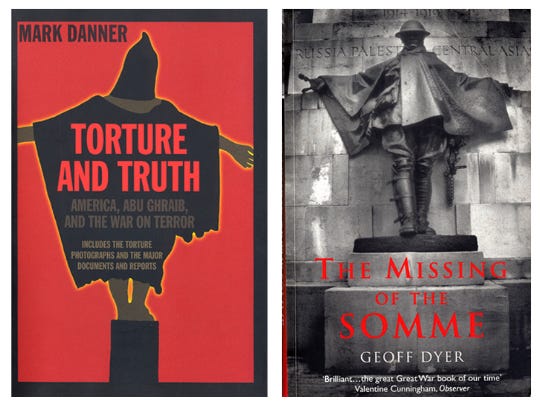

This sort of thing. On the left, the iconic image of the depredations at Abu Ghraib during the Iraq War in 2006; on the right, the monument to the victims of the Battle of the Somme, ninety years earlier, in 1916.

An uncanny resemblance, to be sure, though those who have read thus far may themselves already have realized that both draw on the same Christological base, the outstretched arms which evoke both Christ’s martyrdom and his encompassing grace. This is obvious (and clearly conscious) in the case of the Somme monument, one of many overlooking cemeteries that contain some of the more than 300,000 mortal victims of that horrendous meatgrinder of a battle. The case of the Abu Ghraib image is a bit more complex, for the reference was perhaps not fully conscious on the part of the prisoner’s tormentors (except perhaps in a bad faith sort of way, conscious in the mode of maintaining a resolute obliviousness to the obvious), and in fact the Christological reference in this instance is if anything somewhat doubled and blurred; for not only are his tormentors forcing their victim to spread his arms in that Christlike pose (itself a humiliation for a Muslim), but then, with the added hilarious twist of attaching electrodes to his fingers (electrodes the prisoner would have had no way of knowing were not in fact connected to any live wire), they are simultaneously reenacting that other episode from the passion story, the Mocking of the Christ. Nicely turned: a veritable two-fer.

But instances of Co-Causation turn up in all sorts of other places as well. Thus, for example, the way in which, owing to common atmospheric-gravitational constraints and evolutionary needs, the potential for flight keeps recurring, albeit each time independently, across all sorts of phyla along the tree of life: mammals, birds, butterflies.

Or somewhat similarly—and here we will need to double back on an earlier formulation—the way in which those sedimentary swirls and bubbles floating atop that deep brown cup of cinematic coffee referenced earlier, owing to their apopheniac tendencies (see Issue #12), turn out to look a lot like galaxies and cell structures because, actually, all of them are being formed by and subject to exactly the same physical forces. For more on which, see physicist Sydney Perkowitz’s delightfully informative Universal Foam: From Cappuccino to the Cosmos.

Here, too, one finds a splay of sub-categories, as for instance,

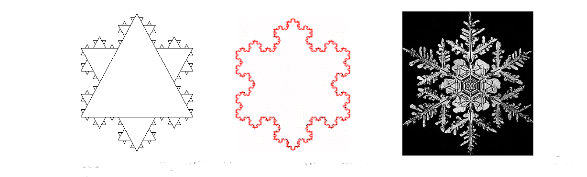

Fractalization

that process whereby the same geometric or topological form tends to repeat at smaller and smaller (or, depending on which way you’re looking at it, larger and larger) scales, across a given entity, as, for example, most famously, in snowflake-like formations.

But for that matter the same phenomenon helps account for the spooky similarity in the morphology of, to the left, the microscopic image of grains of sand, and to the right, the telescopic vantage on one of the moons of Mars.

Fractal landscapes and Algorithmic Financescapes

An intriguing sub-subcategory here is the notion of a fractal landscape. Or as our good friend Dr. Wikipedia explains, “a surface generated using a stochastic algorithm designed to produce fractal behavior that mimics the appearance of natural terrain. In other words, the result of the procedure is not a deterministic fractal surface, but rather a random surface that exhibits fractal behavior.” Wikipedia goes on to offer as an example of this sort of thing

(individual tile-groupings compounded and compounded over and over again according to a particular rule) along the lines of the animate illustration above. And digital artists and animators, noodling around with that notion, have in turn come up with some pretty astonishing likenesses of actual terrain

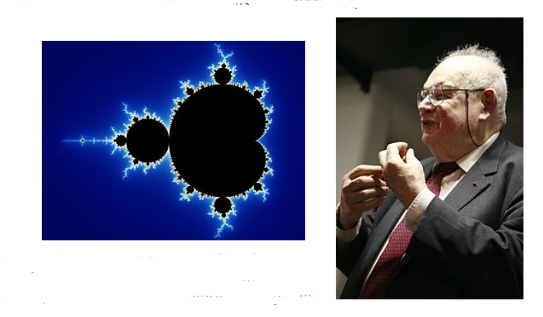

For that matter, Benoit Mandelbrot (1924-2010), the brilliant French-American mathematician who first really developed the notion of compounding fractals with his famous Mandelbrot set,

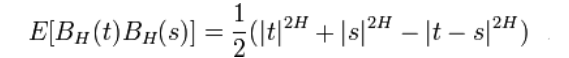

at one point even proposed modeling the Earth’s actual rough surfaces via fractal Brownian motion, using the following algorithmic equation

—an equation which in turn might remind some of you of the sorts of proprietary trading algorithms that have grown rampant all over Wall Street and the world’s other exchanges in recent years, increasingly complex programs that once set in motion require no human intervention and enact huge trades at millionths of a second, based on increasingly abstract mathematical models supposedly derived from the prior history of all trades. One theory has it that, in 1993, when Congress cancelled the mammoth Superconducting Super Collider particle accelerator project in Waxahachie, Texas, it effectively deprived an entire generation of highly trained American physicists of prospects for effective work in their field; whereupon, many of those then drifted over to Wall Street, where they lavished their talents coming up with ever more intricate and faster and faster such algorithms in a sort of fractal arms race, which in turn, many have argued, set the backdrop to the crash of 2008 (an intriguing if catastrophic instance of compounding unintended consequences). Such fractomaniac programs, “algorithms on steroids,” as they are sometimes called—making and unwinding trades at speeds rendering any human oversight impossible—have come to dominate trading on most of the world’s exchanges, and were specifically deemed responsible, for example, for the still-never-quite-comprehended Flash Crash of May 6, 2010, also known as “the Crash of 2:45,” when the market suddenly lost and then just as quickly regained almost ten percent of its value—trillions and trillions of dollars—in just five minutes.

I mention all of this because for a series he was calling “High Altitude,” the German mountain-climber/photographer/artist Michael Najjar recently ran a batch of photographs he’d taken during a climb up Argentina’s 22,840 ft. Mount Aconcagua (the highest peak in both the Western and the Southern hemispheres) through the equivalent of Photoshop, rendering mountainscapes that tracked exactly with timegraphs of various leading economic indicators, including , for example, the Nikkei averages from 1966 to 2009, the Dow Jones averages from 1980 to 2009, and my personal favorite, the Lehman Brothers deathridge from 1992 to 2008.

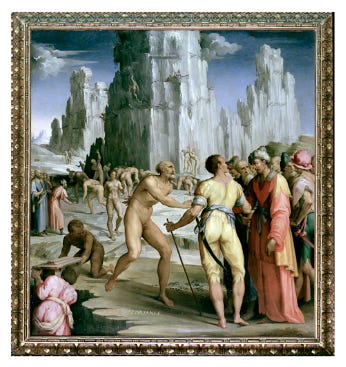

In an essay accompanying the catalog for Najjar’s High Altitude show winningly entitled “Subprime Sublime,” British curator Paul Wombell made a swell convergent catch, likening Najjar’s completely up-to-the-minute hybrid photos to the backdrop range in Maso da San Friano’s 1570 “La miniera di diamanti,”

a “bizarre and extravagant painting” (Cosimo I de’ Medici) depicting men using scaffolds and ropes to scale the face of precipitously rising ridgefaces in order to extract diamonds. “Though there is 400 years difference between ‘La miniera di diamanti’ and ‘High Altitude,’” Wombell went on to note, “you can see the changing world order taking shape. The Renaissance heralds in the scientific method, the importance of mathematics, the intertwining of art and money, the beginnings of European colonialism, and the expansion in international trade that prompted the rise of banking.” A nice, tight loop.

Branching Structures

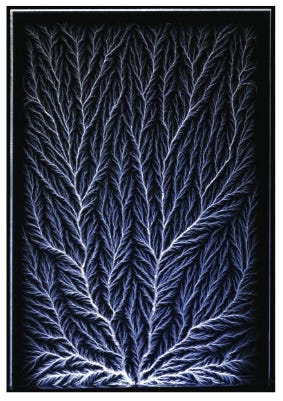

Another sub-sub category in this Co-Causation realm, branching type structures, of the sort we already encountered with Mr. Murch’s contribution to the contest (see Issue #12), similarly evince versions of this fractalizing phenomenon: the twig recapitulating the branch recapitulating the tree and so forth…

And those, of course, one encounters all over nature, in everything from river deltas to—wait a minute, what is that thing below? For starters, is it even animal, mineral or vegetable?

The nerds among you may recognize it from the endpapers of my original Everything that Rises book. Pretty amazing, hunh? Want one for yourself? They’re surprisingly easy to produce. Here’s what you do: Take a slab of clear acrylic Plexiglas and find your way to your nearest linear beam accelerator. The one I happen to have in mind consists of a four-story hanger-like structure with, for all intents and purposes, a huge down-facing television picture-tube nested inside (albeit one with its filament encased in a ten-foot diameter steel pressure vessel surrounded by 200 psi of sulfur hexafluoride gas, for insulation, evincing an acceleration voltage of 5,000,000V in lieu of the 20,000 you’d find in an ordinary picture tube).

Now, get the guys to remove all the stuff they’re ordinarily stiffening up in there (the plastic industrial pipes, synthetic tubing, that sort of thing), and slot your acrylic slab down at the bottom. Get well out of the way, and now give the thing a good stiff zap with all that humongous energy. When you pull the slab out, it may betray a mild yellowish tint, but otherwise it will seem unaltered: just as transparent and unblemished as before. In fact, however, the thing has become supersaturated with stray electrons (so many in fact that there is literally no room for a single other one), gazillions of them momentarily trapped inside (acrylic is an excellent insulator) and just itching to escape (feel the bristling crackle of static electricity as you brush the back of your hand against the block).

Now, set the slab on its side, take a sharp pointed metal rod and give the thing a good solid whack. Suddenly, in the flash of an instant, all those stray electrons will come racing from all about the slab in a headlong dash toward the site of the disturbance: Kaboom, a blinding discharge! Exactly, for that matter, as happens inside a stormcloud as all its stray electrons come madly converging just before it unleashes its lightning bolt. Although in the case of this Lucite slab, unlike with the cloud, the hellbent electrons will have left traces of their escape routes in the encasing plastic (capillaries into tributaries into branches into surging trunks)—a perfect instance of a classic Lichtenberg figure, named for the eighteenth century German humorist and physicist, Georg Cristoph Lichtenberg, who first noted their appearance when he discharged static electricity onto a dust-laden plane. Really cool.

So, go try it, or else pay a visit on Bert Hickman and his cohorts over at www.teslamania.com. They do this sort of thing all the time, and even sell the results of their little science projects: flat electric trees embedded in plastic rectangular slabs, or, even more amazing, three-dimensional trees embedded in rectangular cubes, which looked at from above, look for all the world like spokes converging on a wheel hole.

An interesting question arises as to whether the way in which electricity discharges in patterns like that directly accounts for all those biomorphic instances of the same sorts of patterns—trees, leaves, the neurons and dendrites in our brains

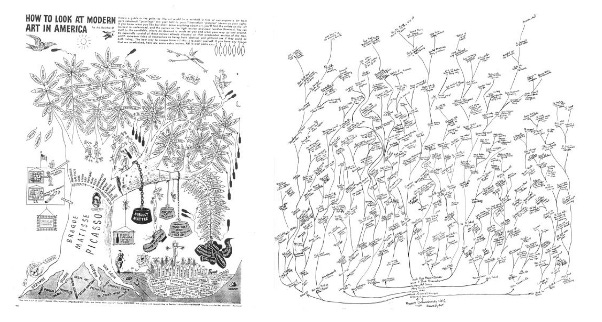

—whether, that is, organic cells actually come to line themselves up along fields of electric force (I sing the body electric!), or rather whether both organic and electrophysical processes are subject to the same wider cosmic forces unfurling across time. And in fact the questions can be taken further (as I did, in the last section of Everything that Rises), because one can’t help but notice how often human thought, generated out of a brain characterized by the mesh of all those branching neuron and dendrite structures, so often evinces itself in the form of branching conceptual trees: family trees, decision trees, and the like. That’s Ad Reinhardt’s genealogical representation of the tree of modern art, from his art comics, on the left; and the artist Beth Campbell’s own work on the right (one her métiers consisting of taking up residence facing a blank white wall at her latest venue and proceeding to trace out the tree of possibilities arising out of an issue currently obsessing her, in this instance whether or not she should become a Lesbian).

Near the end of Everything that Rises, I quoted the neurologist Elkhonen Goldberg from his magisterial 2001 volume, The Executive Brain: Frontal Lobes and the Civilized Mind (p 224), for it seemed he too had been noodling around with such puzzles:

…With this demonstration in place, the following intriguing questions arise: Do the invariant laws of evolution, shared by the brain, society, and digital computing devices reflect the only intrinsically possible or optimal path of development? Or do human beings recapitulate, consciously or unconsciously, their own internal organization in man-made devices and social structures? Each possibility is intriguing in its own right. In the first case, our analysis will point to some general rules of development of complex systems. In the second case, we encounter a puzzling process of unconscious recapitulation, since neither the evolution of society nor the evolution of the digital world has been explicitly guided by the knowledge of neuroscience.

Puzzling, indeed. But what else are we all here for but to puzzle and puzzle away?

Simultaneity

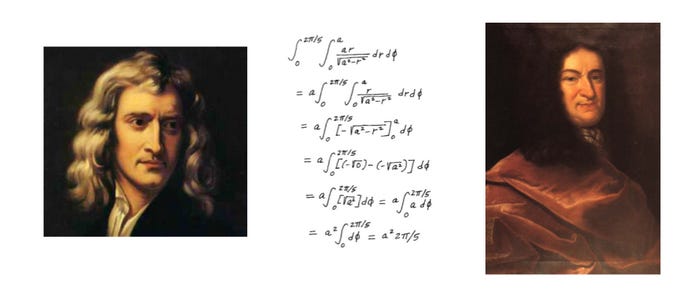

Another version of Co-Causation keeps playing itself out across the history of science and culture, which is to say the sort of thing that happens when almost exactly the same idea occurs to two or more people, seemingly independently, at virtually the same time. As, for example, was the case when both Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz seemed to come up with modern calculus at roughly the same moment in the late 1680s (leading to a spate of bitter accusations of plagiarism flying in both directions).

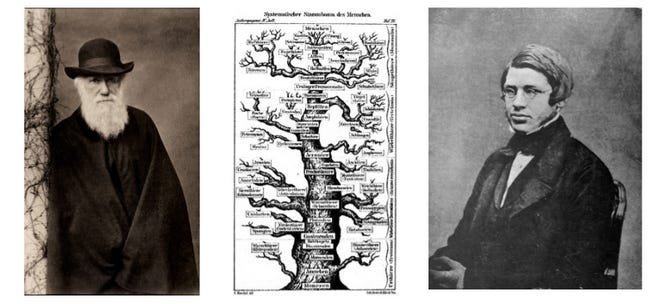

Or later, in the mid-1850s, when the idea of evolution by natural selection seemed to have occurred to both Charles Darwin and Alfred Lord Wallace at the same moment, working though they were, literally, on opposite sides of the planet.

Of course the funny thing here is that the commanding metaphor both had recourse to was one of an endlessly branching Tree of Life (paging Dr. Goldberg). For that matter, wouldn’t it be appropriate in such cases to suggest that the general cultural surround had become so “super-saturated” with the imminence of the idea in question (calculus, natural selection) that there wasn’t room for a single other idea before the notion burst forth, and not all that surprisingly, simultaneously, at two places at once?

Identity

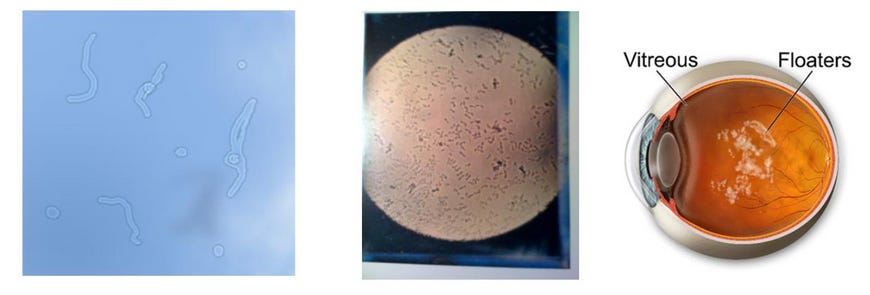

Another entertaining subcategory of Co-Causation can be found in instances of identity, which is to say things look alike because they are in fact the same thing, seen from different vantages. Here a good example is immediately at hand: go outside and look up at the daytime sky. Notice those wispy little threads of microscopic-cell-like structures that seem to float about, drifting toward the side of your vision; you joggle your eyes and they slosh back to the center of your gaze, only to start drifting to the side again. Well, the reason that such “floaters,” for such is their actual technical name, look like microscopic cellular structures is that they are microscopic cellular structures, threads of dead cells floating in the middle of the vitreous fluid which makes up the body of your eyeball, floating that is in a location where the optics of the situation turn your eye into a microscope, capable of surveying the infinitesimal.

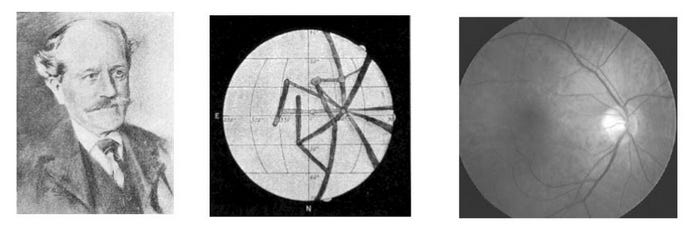

A variation of this pattern can be found in the story of Percival Lowell, the American businessman tycoon and passionate amateur astronomer who became so convinced, looking through his telescope, that he was spying canals on Mars (that’s one of his drawings there below, in the middle), that he went on to fund the construction of some of the premier observatories of his time all over the world, to help further research into the Martian canals.

Alas, apparently what was happening was that he was inadvertently turning his telescope into a sort of ophthalmoscope. You know how when you go in for your annual physical, your doctor shines a light beam into the back of your eye? This has nothing to do with gauging your vision; rather it so happens that vein and nerve structure is most visible (from the outside) at the back of the eye, and that if your veins back there are overly pronounced, you may be subject to early-onset strokes, of the sort that indeed killed Percival Lovell, at age 61, in 1916.

Years ago, as I’ve written elsewhere—and this will surely date me (I was maybe about twenty-five at the time, a cub freelancer on one of my first stories)—I had the idea to go back to my own kindergarten’s playground to see what was passing for humor there among the newbie set.

I just loped onto the field and hung out for a couple days at recess (one could never get away with such behavior nowadays). Anyway, the kids were perfectly happy to regale me with the latest in kid wit, and the point is the jokes were identical, exactly the same as they’d been in my day, and told with the very same oblivious cluelessness. Mommy, guess what? What, Sally? I made a dollar today at school? How’d you do that, dear? The boys bet me that I wouldn’t be able to climb the pole, but I did. Oh, silly, they just wanted to see your underpants. Well, I fooled them: I wasn’t wearing any! Bellylaughs and guffaws all around. And so forth. And it got me to thinking. Because maybe it is the jokes that are the truly living entities on this third planet from the sun, and we, the humans, perhaps merely the endlessly flowing medium in which they abide.

And one final instance within this Identity subcategory. The other day a friend emailed me a photo taken at an upscale McDonald’s in an up-and-coming Brooklyn neighborhood, which the gentrifying manager apparently had taken to decorating with art posters. And if that pair along the wall happen to look to you like Rothkos on their side, that’s because that’s exactly what they are: Rothkos on their side!

Zeitgeist

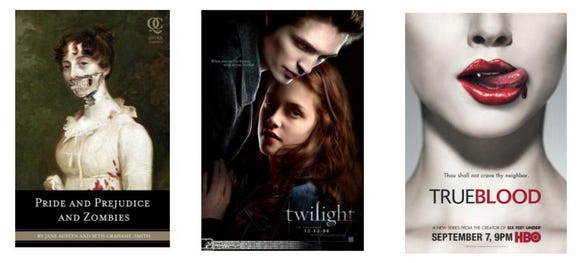

The next drawer over in our Co-Causation case brings us to another one of those somewhat porous subcategories, in this instance expressions of the so-called Zeitgeist. Because, seriously, who really understands why suddenly, a while back, zombies and vampires seemed to be welling up all the hell over the place all at once?

It must have been something in the water, something in the air (in which case, could somebody please do something to clean up the water and the air, because, seriously, enough already).

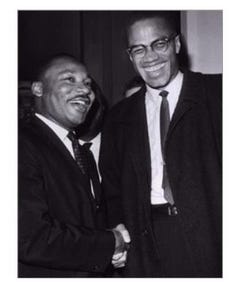

An interesting aspect of these zeitgeist eruptions is that they often occur in bipolar dyads—mild and spicy, as it were. Thus, once you have the Beatles you can expect to get the Rolling Stone; the same with Michael Jackson and the artist eventually permanently known as Prince; and each new Cyndi Lauper can be expected to bring a Madonna in her train. I am sure others more current than me (remember I just turned 70, and how the hell did that happen?) can provide instances more current than those.

This even happens in more serious political contexts: witness, for example, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.

An especially odd manifestation of the zeitgeist occurred a decade back, in 2011, when two films came out simultaneously, films that must have been being shot simultaneously on separate continents by filmmakers who would have had no reason to know about the other, both films deploying the same overriding metaphorical image, and a startling one at that, to the same effect.

I’m not sure I’d go so far as to denominate one of them, Mike Cahill’s Another Earth, as the milder, and the other, Lars von Trier’s Melancholia the more spicy (or anyway more pungent), but the convergence was completely uncanny. In both films a phantom planet long hidden behind the far side of the sun suddenly broke free in its orbit and wheeled closer and closer to earth (a haunting image proffered in the poster and TV advertising for both); in both a young woman was the first to notice the barometric shift in the heavens,

an insight which in both instances (though for different plot reasons) pushed the two heroines (played respectively by Britt Marling and Kirsten Dunst) into profound depressive episodes, at the nadir of each of which, both women launched out into the uncanny night, shed off all of their clothing, and lay down upon the ground to bask naked, mesmerized, becalmed, in the soft stark glow of their looming planet.

Thematically, in Zeitgeist terms, one might surmise that both films reflected a more generally widespread apocalyptic malaise, the sense (what with global warming, water crises, an out-of-control population explosion possibly beginning to bump up against the carrying capacity of the planet, and so forth, not to mention specific quirky periodicities in the Mayan Calendar) of an onrushing End of Times, a sense that was showing up in all sorts of other films and novels and plays as well. But what to make of that naked night bask?

There I think the clue harkens back to the primordial past rather than to any imminent future: to Artemis, that is, Diana, moon goddess, goddess of the hunt, lounging naked in meadows in the midst of one of her own midnight tramps.

Crossed Metaphors

A more focused and concentrated miniburst, as it were, of the Zeitgeist is the sort of thing one gets to see trawling any given week’s political cartoons from around the globe, when it can get to seem like cartoonists all over the place are independently cross-wiring the same two developments in the news. Thus for example, in the days immediately after 9/11, how newspapers all over the country began featuring versions of the same editorial cartoon, linking the fall of the Twin Towers to the vantage of the Statue of Liberty:

A somewhat more entertaining instance occurred about a decade ago, when in the midst of a mounting economic political crisis (centered that week on Berlusconi’s Italy but inexorably welling out throughout Angela Merkel’s Eurozone), the captain of the Italian cruiseliner Costa Concordia, while grandstanding unconscionably for fans on an island off the coast of Tuscany, managed to scrape too close to the craggy shore and sank the entire ship, apparently, for good measure, abandoning the vessel while passengers were still on board.

The confluence of themes proved irresistible catnip for cartoonists, and the next day there occurred a veritable algae bloom of such spot drawings (believe me, these are only a few, there were dozens).

Memes

More concentrated and focused expressions yet of the Co-causative Zeitgeist are the sorts of things that currently go by the name of “memes”—momentary tropes so startling or peculiar that they almost instantaneously take the internet, as it were, by storm.

Thus for example, several years back, a helmeted black-uniformed policeman at the University of California at Davis took a quite leisurely stroll along the outer flank of a peaceful sit-in of students protesting tuition hikes, blithely squirting pepper spray into the eyes of all and sundry, an image so bizarrely unsettling that it quickly mutated into all manner of other contexts as the meme of the pepper-spraying policeman ran rampant across the web.

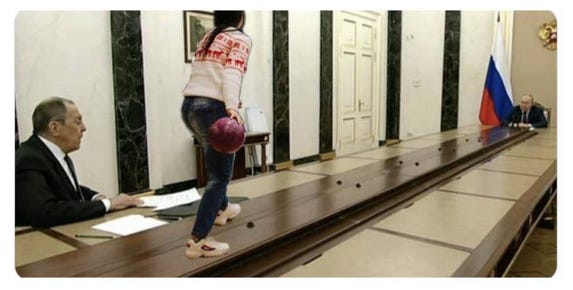

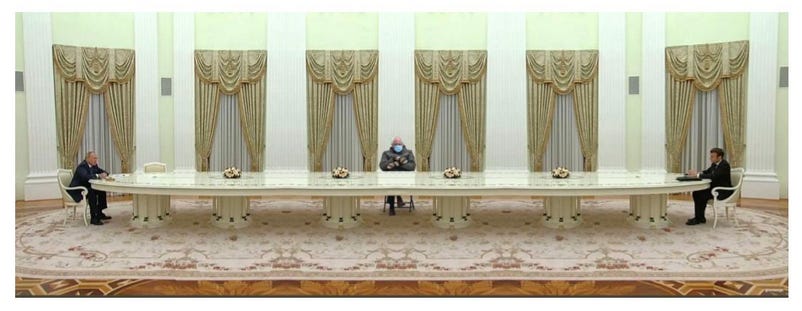

More recently, in fact just the other day (although how long ago it already seems), we had the marvelous meme of Covid-haunted Putin (in his late Howard Hughes phase, that of course being another meme) entertaining supplicating guests at his long, long table (handily gathered for us by Shaun Walker on his Twitter feed).

View the animated version here.

And then, of course, a further mashup with the Meme of the Year (or last year, anyway):

Other memes—slightly more slow motion—take the form of verbal ticks that suddenly seem to afflict everyone at once. “Really? Really?” Yes. Really, really. Or back in the day, before the internet, they might have taken the form of so-called “earworms,” those tunes you couldn’t get out of your head, no matter how hard you tried —and nor could anybody else.

In each instance these cultural eruptions take the form of infestations, of viruses, and no wonder. The term has its origins—or should I say, the origin of the Meme meme traces its way back to a kind of Patient Zero (itself another meme):

the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who originally coined the term in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, drawing on the Ancient Greek word mimeme, which is to say “something imitated.” (“I wanted a monosyllable,” Dawkins subsequently explained, “that sounded a bit like gene.”) Over the years, it has come to mean “an idea, behavior or style that spreads from person to person within a culture” (Merriam Webster Dictionary—“culture” in that formulation being both a pun and a meme!), but from the start Dawkins wanted to emphasize the way memes may evolve in much the ways that genes do, by such processes of natural selection as variation, mutation, competition, and inheritance—and that just as with his theory of the selfish gene, the more robust the meme, the greater its chances of success in its wider surround, which is to say the populace at large.

The really good ones survive year after year—think back, in this context, to those improbably sturdy puerile jokes on my old kindergarten playground—and give rise, as does Dawkins’s selfish gene theory, to the question of just who is piggybacking whom—are organisms or their genes the true agents of natural history? Are individuals or their stories? Suffice it to say that in both instances the less robust ones presently go extinct.

Which finally puts me in mind of a piece I was reading the other day by Eliot Weinberger, one of our finest essayists, the brief turn on “Naked Mole Rats” in his 2000 Karmic Traces collection. Strange strange creatures, those naked mole rats deep in the highly ordered tunnels from which, blind, they never emerge, and strange too the temper of their social organization:

They are continually cruel in small ways, clanking teeth, breathing rapidly, biting, pulling one another’s baggy skin, shoving each other sometimes a yard down the tunnel. But only the females who compete for the role of [the entire colony’s solitary] breeder inflict real harm. Wounded, the defeated female crouches shivering in the toilet [chamber], ignored by the others until she dies. (p.54)

Is that how it is, I found myself pondering as I read (as I suspect Weinberger fully intended that I ponder) with ideas, too—both in the wider community’s history, and in the history of each individual mind?

* * *

AN INTERLUDE

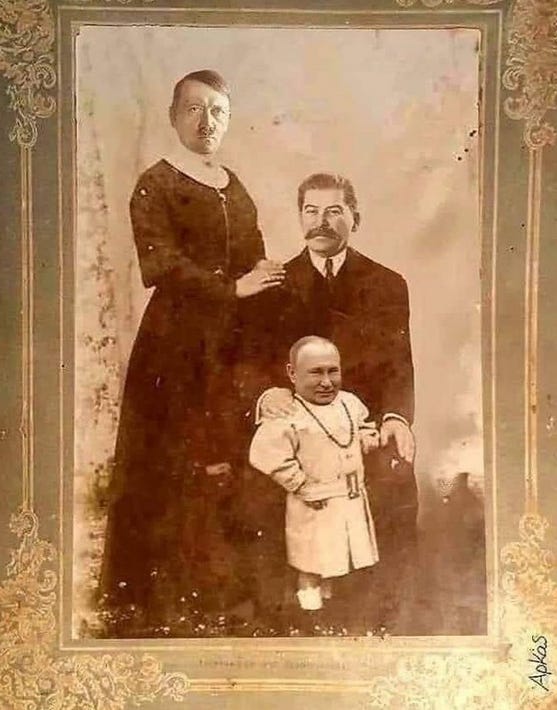

And finally, as far as this issue’s episode of the All that is Solid processional is concerned, as promised, a more immediate sort of interlude, kind of a cross between a Crossed Metaphor and a Meme (with intimations, for that matter, of near-Identity): the trope of Baby Putin.

I owe a debt of gratitude in this instance to my friend Michael Benson, a connoisseur of these sorts of crossed-wire representations from that part of the world (see his prophetic nightmare of a documentary, Predictions of Fire, limning the late Yugoslavian cultural moment as the country descended into the Bosnian wars, here), for alerting me to this particular family pastiche which appears to have been circulating about the Ljubljana internet (author not known to either of us, though it immediately put both of us, separately, powerfully in mind of the Szymborska poem).

But the point is that the last few weeks have seen a veritable upwelling of images of the same sort:

All of them keying off of this strange historical moment when the current Russian leader garbs himself in the aura of that earlier patriarch of the Great Patriotic War, launching a veritable blitzkrieg on a neighboring sovereign country, attempting to enforce a sort of Anschluss, under pretenses of trying to “denazify” the place. But does that make this particular Manchild the spawn of Hitler, or of Stalin, or indeed, as some of these current artists are suggesting, of both?

The thing is, this trope of the infant and the parent itself has a striking history in this part of the world. Indeed, several years ago, after the Crimean invasion but before this more recent onslaught, as Putin was already deep into consolidating his singular autocratic powers, an obverse image began appearing across the Russian twittersphere, a sort of view through the flip side of the telescope, in which it was Daddy Putin who was holding up, as the baby image of his new regime, none other than Baby Jozef (in his guise as a representation of the true nature of the rapidly reemerging regime). Any Russian who came upon the anonymous (as far as I have been able to make out) image would surely have caught the reference to one of the most famous agitprop representations of that earlier Father of the Nation.

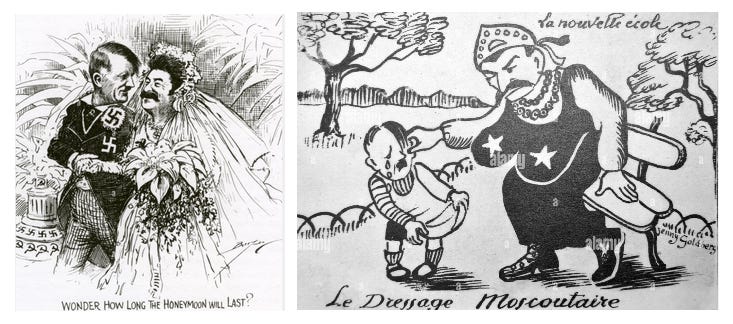

And for that matter, the dread prospect of a marriage of Hitler and Stalin itself goes back deep into the historic subconscious of that part of the world, for what else was the horrifying Nazi-Soviet pact of 1939 than the belated revelation of their secret betrothal? (Note the gender reversal from the photoshopped Apkos above.)

Having said all of that, however, the trope of the Baby Putin plays so trenchantly in this instance not only because it suggests a lineage but because it also performs an infantilization, one that also has a history in this part of the world, as in Jenny Goldberg’s 1943 image of whippersnapper Hitler getting a good dressing down, a la Moscoutaire, at the hands of Mommy Stalin. Is it perhaps too much to hope that one of these days, a similar image might arise, of baby thug Putin getting his own comeuppance at the hands of Matron Zelinsky, the Servant, indeed, of her People? Who knows.

* * *

A-V ROOM

My conversation with Chilean novelist Benjamin Labatut about his latest novel: When We Cease to Understand the World

“Nothing is too beautiful to be true “ (in the words of Michael Faraday) being a phrase readers may find thrumming in the back of their minds as they tear through the chapters of the short new hyper-parabolic novel, When We Cease to Understand the World, (recently out from NYR Books in the US), a work of “fictive nonfiction” in the coinage of its prodigiously gifted young Chilean author, Benjamin Labatut. But beautiful, they may slowly come to realize, in the specifically Rilkean sense (beauty being “nothing but the beginning of a terror we can only just barely endure, and we admire it so because it calmly disdains to destroy us”); for the angels that this novel’s protagonists--several of the greatest physicists and mathematicians of the early twentieth century (Haber, Einstein, Schwarzschild, Heisenberg, Schrodinger, and Griesedieck, among others)--take to wrestling, vertiginously, along the very rim of the yawning dawning abyss of quantum mechanics, are terrible indeed.

Benjamin Labatut was born in Rotterdam in 1980 and spent his early years caroming with his family between The Hague, Buenos Aires, and Lima before settling in Santiago at age 14. His third novel, When We Cease to Understand the World (originally titled Un verdor terrible), has been developing an avid following throughout the world, was shortlisted for last year’s Booker International Prize, and is a finalist for this year’s Art Seidenbaum Prize as the Book of the Year, the winner to be announced later this coming month at the LA Times Book Festival. Which makes it seem like a good time to reprise the conversation I had last October with Labatut, as part of the wider series I curated for the Venice Architectural Biennale, in conjunction (in this instance) with the Community Bookstore of Brooklyn.

* * *

And speaking of things being just too damn beautiful to be true

INDEX SPLENDORUM

No sooner had we featured Daniel Crooks’s Imaginary Object #3 in the INDEX of our last Wondercabinet (#12) than our colleagues over at thisiscolossal.com called our attention to the short film Bellatrix, depicting ice in the very process of crystalizing into radial stars, as captured by the French video artist Thomas Blanchard (and scored by Sébastian Guérive).

Talk about convergences! Talk about pillows of airs lodged in our drop-jawed mouths.

For those of you who might hanker after some sort of explication as to what’s going on across these hypnofying images, consult the introduction to Colossal’s presentation here.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

***

NEXT ISSUE

Up till now, with our All That is Solid Taxonomy, we have by and large been examining culturewide convergent effects; with the next issue of the Wondercabinet we will begin exploring Direct Influence: the kind of things that happen when one artist or thinker or group of such artists or thinkers impacts upon another—both forward and backward, and consciously and unconsciously: Socrates and Jesus, Eliot on Dante and Virgil, Mark Twain and Kurt Vonnegut, Jesus and Ché, and onward from them. And Robert Irwin at age 92 has a new show in New York, and it may be one of his best ever: attention needs be paid, and will be. And more…

***

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button below), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

I am in awe of the depth and range of your writing. The visuals' layout and clarity is a work of art. I also post on cultural topics on substack under turfwall but lacking as yet any visuals. My posts are more digests on a particular topic but planning to expand scope. I would appreciate any feedback.

Stephen