March 17, 2022 : Issue #12

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Hello again. To begin with this week, further thoughts and echoes welling up from a consideration of the ongoing Ukrainian catastrophe: a twinning of flag images, and pertinent poems by Auden and Herbert. And then, continuing on with our TAXONOMY OF CONVERGENCES, which is to say the first section of the taxonomy itself, ranging from categories of Apophenia through Accidents (or Coincidences) on past Affinities; featuring John Hodgman and a pope on Fire. Then another FOOTNOTE, this one on stasis and movement across the first several decades of nineteenth century still photography. And in the INDEX, three videos from stuttered-sliced-and-smeared movement-magus Daniel Crooks.

* * *

LEAVES FROM MY COMMONPLACE BOOK

To the left, of course, Delacroix’s instant commemoration of the July Revolution of 1830, which toppled King Charles X of France. To the right, a photo from the June 1956 protests in Poznan, Poland, when workers stormed out of their factories protesting working conditions and got met with ruthlessly violent repression (over fifty of them were killed). Partly no doubt owing to its rhyme with the Delacroix, this was the image (long suppressed though it was) that became iconic of the event in a subterranean sort of way across the decades that followed: a woman in white leading a throng of protesters with, above them, a Polish flag that had been dipped in the blood of one of their comrades. Indeed so pervasive was knowledge of the repressed image that when Solidarity came surging into existence years later, all its graphic artist Pawel Udorowiecki needed to do in June 1981, to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of that earlier uprising, was to create a poster with the name of the place and the date overlain across a blood-stained Polish flag, and everybody knew what was being referenced. Last week, the graphic artist behind the cover image for The Economist had recourse to almost the same imagery, this time with a Ukrainian flag, and no need, alas, for any caption.

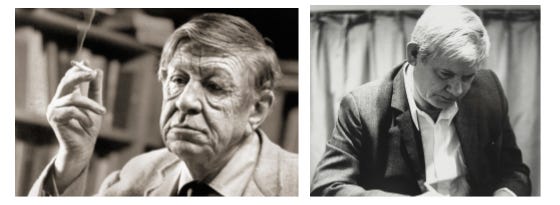

Meanwhile, here follow two further classic poems grimly, newly pertinent to our sudden moment, both suggested across a recent conversation with the poet Vijay Sheshadri, who is no mean oracle himself: the first, W.H. Auden’s response to the Soviet quashing of the Prague Spring in 1968; and the second, Zbigniew Herbert’s to the imposition of martial law which brought an end to the first incarnation of Solidarity, in Poland, in 1982.

August 1968

by W.H. Auden

The Ogre does what ogres can,

Deeds quite impossible for Man,

But one prize is beyond his reach:

The Ogre cannot master Speech.About a subjugated plain,

Among the desperate and slain,

The Ogre stalks with hands on hips,

While drivel gushes from his lips.

[W.H. Auden, City Without Walls and Other Poems, Random House, 1970.]

*

Report from the Besieged City

by Zbigniew Herbert

Too old to carry arms and fight like the others—

they graciously gave me the inferior role of chronicler

I record—I don’t know for whom—the history of the siegeI am supposed to be exact but I don’t know when the invasion began

two hundred years ago in December perhaps yesterday at dawn

everyone here suffers from a loss of the sense of timeall we have left is the place the attachment to the place

we still rule over the ruins of temples specters of gardens and houses

if we lose the ruins nothing will be leftI write as I can in the rhythms of the interminable weeks

monday: empty storehouses a rat became the unit of currency

tuesday: the mayor murdered by unknown assailants

wednesday: negotiations for a cease-fire the enemy has imprisoned our messengers we don’t know where they are held that is the place of torture

thursday: after a stormy meeting a majority of voices rejected

the motion of the spice merchants for unconditional surrender

friday: the beginning of the plague saturday: our invincible defender

N.N. committed suicide sunday: no more water we drove back

an attack at the eastern gate called the Gate of the Allianceall of this is monotonous I know it can’t move anyone

I avoid any commentary I keep a tight hold on my emotions I write about the facts only they it seems are appreciated in foreign markets

yet with a certain pride I would like to inform the world

that thanks to the war we have raised a new species of children

our children don’t like fairy tales they play at killing

awake and asleep they dream of soup of bread and bones

just like dogs and catsin the evening I like to wander near the outposts of the City

along the frontier of our uncertain freedom

I look at the swarms of soldiers below their lightsI listen to the noise of drums barbarian shrieks

truly it is inconceivable the City is still defending itselfthe siege has lasted a long time the enemies must take turns

nothing unites them except the desire for our extermination

Goths the Tartars Swedes troops of the Emperor regiments of the Transfiguration who can count them

the colors of their banners change like the forest on the horizon

from delicate bird’s yellow in spring through green through red to winter’s blackand so in the evening released from facts I can think

about distant ancient matters for example our

friends beyond the sea I know they sincerely sympathize

they send us flour lard sacks of comfort and good advice

they don’t even know their fathers betrayed us

our former allies at the time of the second Apocalypse

their sons are blameless they deserve our gratitude therefore we are grateful

they have not experienced a siege as long as eternity

those struck by misfortune are always alone

the defenders of the Dalai Lama the Kurds the Afghan mountaineersnow as I write these words the advocates of conciliation

have won the upper hand over the party of the inflexibles

a normal hesitation of moods fate still hangs in the balancecemeteries grow larger the number of defenders is smaller

yet the defense continues it will continue to the end

and if the City falls but a single man escapes

he will carry the City within himself on the roads of exile

he will be the Citywe look in the face of hunger the face of fire face of death

worst of all—the face of betrayaland only our dreams have not been humiliated

(Warsaw 1982)

[Ζbigniew Herbert, Report from the Besieged City and Other Poems, translated from the Polish by John and Bogdana Carpenter, Ecco Press, 1985.]

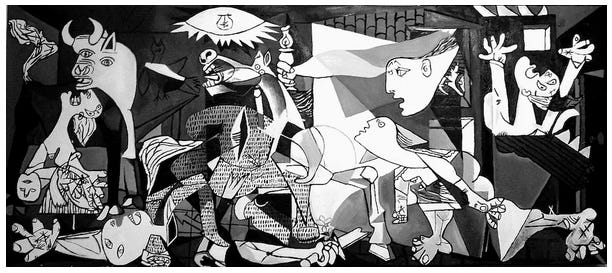

The Herbert poem seemed particularly resonant in recent days, as we continued being collectively transfixed by the seemingly endless martyrdom of Mariupul, the once vibrant town of 400,000 (the Ukraine’s tenth largest) off the coast of the Azov Sea, still under strangulating siege by “liberating” Russian forces—the site, for example, of that horrific shelling of the maternity hospital. The Pope singled out that incident this past weekend in remarks to pilgrims gathered in St Peter’s Square, noting how the town’s name—Maria Polis, city of Mother Mary—rendered its dreadful fate all the more telling. I momentarily imagined him in his popemobile personally leading one of those emergency convoys of rescue buses and humanitarian supplies that the Russians keep turning back. What would they do, I found myself wondering, faced with that prospect? For that matter I found myself wondering whether there wouldn’t be some legal method (perhaps by way of the International Court of Justice in The Hague) of permanently seizing those hundreds of billions of dollars from Russia’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (currently provisionally sequestered in Western banks pending the conclusion of the war), and earmarking them instead as reparations toward the eventual repair of Mariupul and all the other devastated towns and villages and victims left behind by Putin’s senseless war of aggression (while letting the International Criminal Court, also in The Hague, deal with him). But mainly I’ve been thinking about Picasso’s Guernica, and whether Mariupul might already be inspiring some visual artist somewhere toward a similarly epic act of summary witness, and wondering who it is and what form that act will take (myself I bet it is going to be some kind of video, along the lines of Arthur Jafa’s “Love is the Message, the Message is Death“).

* * *

And now, on to This Issue’s Main Event:

All That is Solid:

Toward a Taxonomy of Convergences & A Unified Field Theory of Cultural Transmission, PART TWO

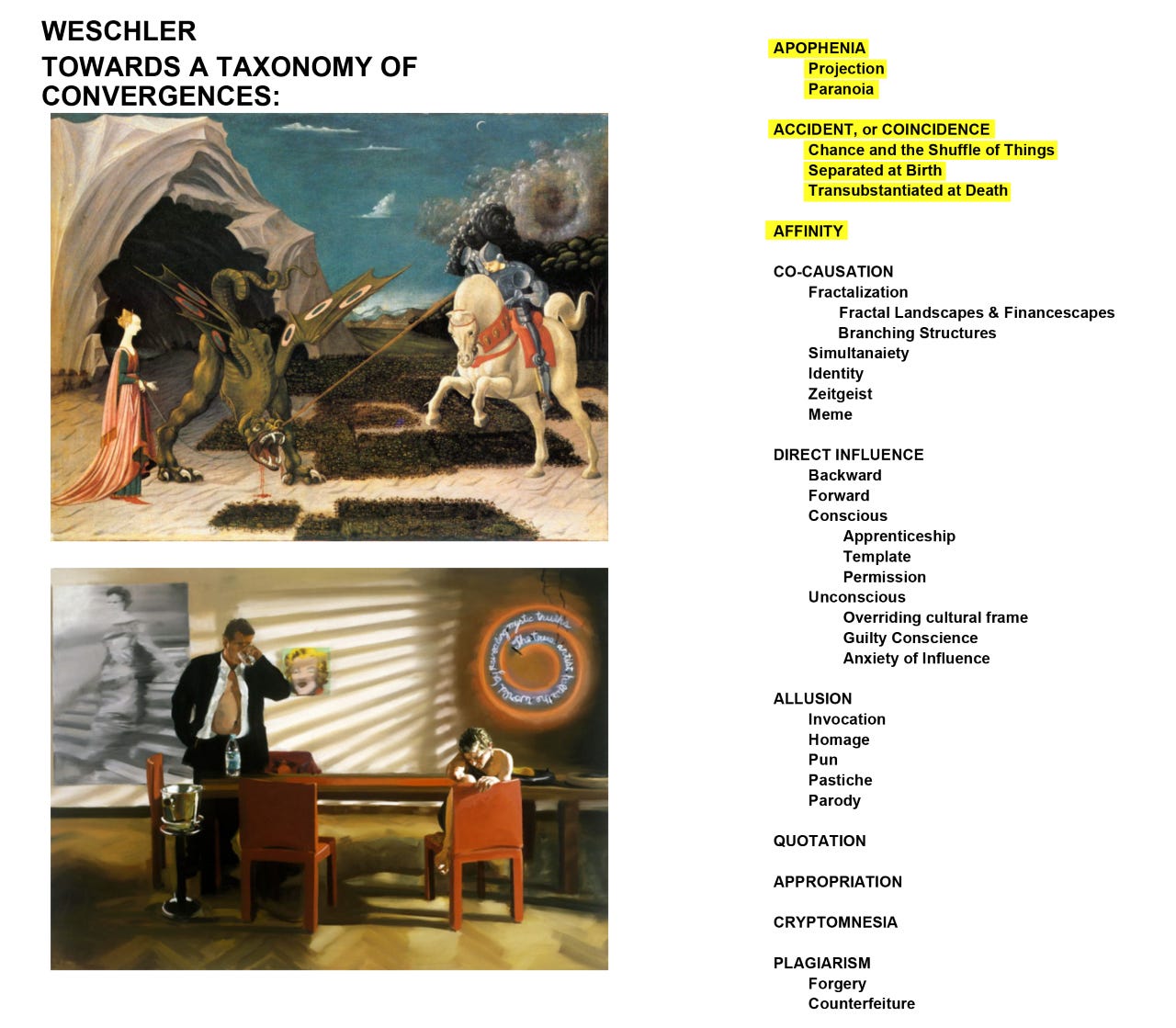

For some reason, that was the contest-submitted convergence that got to me: Fischl’s couple and Uccello’s St. George. Because it was one thing to notice a convergence like that, but quite another to establish exactly what sort of thing was going on, the sorts of claim that were being made, across the myriad of convergent effects the contest kept churning up.

So I decided it was time I set my house in order. Or rather, say, in the manner of a Victorian butterfly collector, to contrive a sort of taxonomy, a series of drawers, one ranged beside the next, into which I might successively install various such convergent claims, one beside the next. A typological spectrum, as it were, spanning the possibilities, with instances supplied for each. And then maybe, once I’d accomplished all that, I’d be able to go back to Messieurs Fischl and Uccello and try to figure into which slot their dalliance might best fit.

Are you with me?

*

Okay, so to begin with, at what we will call the far left extreme of our spectrum, there’s:

APOPHENIA

Excellent word, I hope you’ll agree (gifted to me by the endlessly gifted Mr. Murch), but wait till you hear what it means: The tendency of human beings to see patterns where there are no patterns. Is that cool, or what? Didn’t we always need a name for that? (I fully expect now to see whole spates of avant garde movies, poems, books of poems, novels, rock bands, probably even entire cults suddenly sprouting forth with that name.)

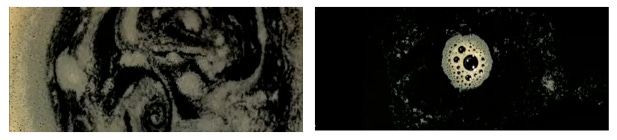

As an instance here we might cite that marvelous scene from Jean Luc Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know about Her (1967)—“Her,” as you will recall, being the city of Paris, though in this particular scene she’s the film’s protagonist Juliette (Marina Vlady), a sophisticated though bored bourgeois housewife and sometime prostitute, who has just entered a café, sat herself down in a corner, and ordered an espresso. I should caution that notwithstanding my YouTube link to the scene above, it’s kind of pointless to sample the scene on your phone or laptop: you really need to have seen it splayed across the big screen in some arthouse movie theater (and who knows if that will ever be possible again), because the point is that presently her languorous gaze makes its way down to the cup before her, and then into the cup, the whole screen (the whole theater!) thereupon filling up with the swirling deep brown liquid of the stirred cup, the brownish white bubbly sediment swirling lazily about its surface. (Don’t even bother trying to follow Goddard’s gnarly muttered voiceover.) And I defy any viewer to gaze upon that scene and not conjure a spiral galaxy swirling about a deep brown firmament.

Or else later, when a different clump of bubbles starts gathering, one beside the next and then breaking apart: a single cell dividing and dividing again: the very origins of life. Or all of it, for that matter, like thoughts frothing and turning, turning and bubbling over, over and out…. Except that, actually, no, there’s absolutely nothing there: we are gazing neither up into the dome of a planetarium nor down the barrel of a microscope, nor even across the figments of our own mind. It’s just coffee sediment, turning and turning, the flash of a silver teaspoon parting the waters.

Like I say: apophenia.

Now, the category “Apophenia” itself parts into a few subcategories. There is, for example,

Projection

which is indeed the sort of thing we come upon in those Rorschach tests, the chance neutral inkblots onto which the viewer is invited to project all manner of associations from out of his own imagination (some viewers, granted, apparently more so than others).

Which by the way reminds me (see what I mean?) of that guy who goes to a shrink and throws himself at the good doctor’s mercy, “Please Doc, you gotta help me, I can’t take it anymore.” Whereupon the Shrink reassures the Guy: Calm down, calm down, let’s just do a little test here and, quick as that, we’ll figure out what your problem is. The Shrink takes a pile of cards, turns the top one over, and shows it to our harried friend: simple—two parallel vertical lines. “Oh my God!,” the Guy positively cringes, “that’s two people and they’re k-k-kissing, and it’s disgusting.” Hmmm, thinks the Shrink, he jots down a few notes, and turn over the next card: two parallel horizontal lines. “Oh my God, are you kidding me?” sputters our friend, veritably wincing in revulsion. “That’s two people, and they’re in b-b-bed having s-s-s-sexual intercourse, and it’s positively r-repulsive.” The Shrink looks the Guy up and down, jots a few further notes, reaches for the next card, turns it over—two crossed lines—at which point our friend blanches, as if on the verge of fainting, “Oh my Heavenly Lord, my God, are you out of your mind, that’s….” Okay, pronounces the Shrink, Let’s stop right here, I can tell you what your problem is: you have a pathologically dirty mind. “I’ve got a dirty mind?” vesuviates the client. “You’re the one showing me the dirty pictures!”

Which, come to think of it, may illustrate a slightly more focused and pathological subset of Projection, which is to say

Paranoia

a rampaging fever of projection in which everything begins to seem to fit into an obsessively ordered hypersignificance, the sort of thing one saw for example in that twisted 2007 Jim Carey vehicle, The Number 23, in which everything in the protagonist’s world presently began adding up to 23, to compoundingly dire effect.

Or else, for example the sorts of things one finds in fringe political movements of one sort or another, take for instance this guy to the right here, who, according to his sign, clearly had it all figured out, since when it came to God and Obama, it was manifestly obvious that neither one of them had a birth certificate (whatever that might have portended). Or next to that, the marvelously inspired cover for a Spanish edition of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which purports to prove that Jews are responsible for all of it, not only (as the puppeteer’s digits patently reveal) for Capitalism, Communism, Freemasonry and Christianity but for Nazism as well! Great. Glad that’s settled.

Though it does remind me of this radical Serbian nationalist journalist whom I found myself sitting beside one day in the galleries at the Yugoslav War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague, who leaned over at one point to explain to me, sotto voce, how all of history was a conspiracy between the Germans and the Jews to do in the Serbian Nation. Hmmm, I countered, at length: where does that leave the Holocaust? “Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?” came his sage reply.

Needless to say, this sort of thinking has now run rampant (or should I say ramQant?) across our own political ecosphere.

Anyway, so much for Apophenia and its progeny. Moving over a notional drawer, though, we come to

*

ACCIDENT (or coincidence)

which likewise opens out onto various subcategories, for instance:

Chance and the Shuffle of Things

(a formulation I owe to Sir Francis Bacon, in some ways the patron saint of this whole mad categorizing enterprise, who, in his “Advancement and Proficience of Learning, Divine and Human,” back in 1605, advised any self-respecting would-be magus to procure himself “a goodly huge cabinet, wherein whatsoever the hand of man by exquisite art or engine hath made rare in stuff, form, or motion; whatsoever singularity, chance, and the shuffle of things hath produced; whatsoever nature hath wrought in things that want life and may be kept, shall be sorted and included.”)

Here for example you find this sort of thing, a couple facing pages from an issue of The Economist, a few years back, wherein the hatted guy from the ad on the verso page somehow traverses the gutter straight into the illustration for the article on the recto page opposite. Weird , to be sure, but then again perhaps not all that weird, given the number of times figures in ads manage to stay put and migrate precisely nowhere.

But then again, what are we to make of this? A full-page ad launching a new campaign for Lufthansa, prominently featured in The Economist and elsewhere the week before the horrendous events of 9/11, and then the front page of Time the week after. What the….?

This is the sort of chance occurrence which, granted, tends to slide back into the “Paranoia” category, which in turn makes this is as good a place as any to note that none of these are hard and fast categories: as in any good spectrum, instances do tend to bleed in and out of their otherwise steadfast definitional confines.

Then we come to that sly and wry subcategory commonly known as

Separated at Birth

a term first promulgated several years back by those mischievously subversive young editors at Spy magazine—they even ended up promulgating an entire volume of such instances with Mick Jagger and Don Knotts on the cover, who you have to admit do look uncommonly alike, whatever that might mean.

But then what’s to be made of Keith Richards and W.H Auden, two shiningly wracked testaments to British artistic sobriety.

Or for that matter, Charlie Watts and Buster Keaton, the latter of whom, come to think of it, sure looks like Samuel Beckett (who cast the aging dilapidated Keaton in some of his own short films), all of whom turn out to be spitting images for Ludwig Wittgenstein (who likewise used to wile away the hours between brainstorms, rapt, attending Keaton screenings, his favorites, at the local Cambridge cinema). There’s even a marvelous essay by Robert Goff on Wittgenstein and Buster Keaton (gathered in the Laughing Matters collection edited by Jonathan Miller) which argues not so much for the philosophical depths of Buster Keaton as for the comic sublime in Ludwig Wittgenstein. Such that some of these Separated at Birth instances (Jagger/Knotts) may mean nothing at all (or at any rate one sure hopes not), whereas others seem to open out onto all manner of connotation.

I offered another example of the latter type back in Everything that Rises with a side by side comparison of Newt Gingrich and Slobodan Milosevic in an essay entitled “Pillsbury Doughboy Messiahs”

—not so much their looks, or anyway not just their looks, as their respective careers. Now please, hold off on the angry letters, I am in no wise suggesting that Gingrich was a war criminal (or, as he would intone in a context like this, “not to my knowledge at any rate”); rather I am suggesting the way that both were empty ciphers with no apparent core convictions except fervent belief in their own manifest destinies, until the one stumbled on “Serbian nationalism” and the other literally focus-grouped his way to the so-called Contract with America, both of them almost simultaneously skyrocketing to power, but then both of them, again almost simultaneously, losing control of the True Believers their cynical gambits had helped to spawn, each in his own way then plummeting from power. I couldn’t help but notice, incidentally, how during the subsequent 2012 Republican presidential primaries when Gingrich was attempting that improbable comeback, no less than Stephen Colbert had recourse to that same Pillsbury Doughboy Macy’s Day parade blimp image in skewering The Newtster.

But perhaps more bizarrely I couldn’t help but notice over the ensuing years a veritable proliferation of Pillsbury Doughboy Messiahs on the Republican Right—from Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck

on past Karl Rove and Dick Morris and Antonin Scalia

on through to the Godfather, as it were, of the Pillsbury Doughdom, Fox News chief Roger Ailes, who liked to spice his broadcasts with lithesome news-bimbettes, much in the manner of Jabba the Hut.

For that matter, once I started noticing the pattern, I started seeing it everywhere across history, all those short squat Doughboy megalomaniacs (Napoleon, Mussolini, Göring).

Which I have to admit somewhat unsettled me, so I called up my sometime pal John Hodgman, self-styled world’s greatest expert, to ask him what he made of this clusterfudge of convergences, but he claimed not have a clue what I was talking about.

At any rate, so we have the Separated at Birth subcategory, but then as well comes the

Transubstantiated in Death

which, of course, is where we find our drainpipe, window condensate, and toast Madonnas, our shrouds and shady Jesuses —excuse me, let’s pause for a moment

on that last one. It seems someone one summer day in a small parched hamlet way in the Outback of deep desert Australia noticed how the leaves on a scraggly local tree during a particular time of the afternoon cast a shadow onto a neighboring fence that he became convinced looked just like the face of Jesus, and suddenly pilgrims from all over the continent began converging (as it were) on the town to witness the miracle for themselves, entirely overrunning the place’s limited hospitality capacities, wreaking unholy mayhem, that is till the advent of autumn, when the leaves thankfully fell from their branches and life returned to normal. This is the category into which one might likewise file the Shroud of Turin (unless, of course, it’s Not). Nor is this sort of thing an exclusively Christian phenomenon: during an Israeli incursion into Lebanon a while back, a West Bank shepherd was stupefied to discover the name Allah expressing itself, in Arabic, across the wooly flank of one of his charges (which must have portended something). And nor, for that matter, is it an exclusively religious phenomenon: witness Princess Kate’s lovely visage taking material form on the face of a jellybean.

But it is mainly religious: a year after the death of Pope John Paul II, in the midst of widespread calls to hasten his beatification, the citizens of his native Krakow stoked a bonfire in his honor. One photographer snapped a shot of the fire, rushed back to his darkroom and witnessed a remarkable likeness welling up from the developing pan.

Now think about this for a minute: anyone who has ever stared at a fire knows that the flames never look like anything for very long (except perhaps like other lapping flames): they lap and already they’re gone. The likeness in this case never actually occurred except in the instant grab of the camera. Notwithstanding which, hordes of true believers latched onto the photo as yet further evidence in the case for instant beatification. As it happened, just around the same time, up in Warsaw, an exhibit of work by the Italian art-provocateur Maurizio Cattelan included his installation, “Pope hit by a meteorite,” which portrays exactly that, and a rather startlingly lifelike approximation at that; perhaps not that surprisingly (or at any rate unpredictably), the installation caused a huge scandal among the pious and eventually had to be closed off. Not surprisingly, yes, and yet, what exactly’s the deal here? Pope hit by meteorite? Sacrilege! Pope on fire? Yet further evidence in support of a fast track to sainthood!

Finally in this subcategory—and I’m not sure whether we’re dealing with matters secular or religious here—not that long ago, the internet lit up with frantic links to one of NASA’s pictures of the day, a gorgeous flare erupting off the sun’s surface, which on closer examination looked quite uncannily like…well, as I keep saying, you go figure.

*

AFFINITIES

Alright then, moving one case over so as to open the next drawer, we come to a curious nether category—neither an accidental happenstance, really, nor the effect of some sort of co-causation. A frisson, as it were, of sensibility, often seen occurring across cultures, when creators in one tradition suddenly experience a strong sense of fellow feeling while encountering the work of confederates working out of an entirely different tradition.

Perhaps most famously (and controversially) under this category in recent decades was William Rubin’s “Primitivism in 20th Century Art” show at the Museum of Modern Art back in 1984, which sought to trace, in its own words, “affinities between the tribal and the modern” but wound up ruffling all sorts of feathers among theorists of post-colonialism (indeed virtually single-handedly launching the entire academic post-colonialist industry).

Critics attacked the show, variously, for slighting the tremendous violence done to native populations as imperialist regimes wrested all manner of resources (and incidentally artifacts) from their rightful owners, not to speak of the elitist condescension exercised upon one side facing the other through the use of that loaded term “primitive.” (Regarding that latter problem, the anthropologist Sally Price racked up a particularly trenchant set of points in the introduction to her 1989 book Primitive Art in Civilized Places, lining up two separate sorts of definition of the term “primitive”: first the conventional, such as “the art of people whose mechanical knowledge is scanty—the People Without Wheels” or “art produced by people who have not developed any form of writing”; and then a set of definitions less conventional but perhaps more telling, such as “Any tradition of visual art produced by mentally balanced adult human beings that is regularly analyzed in the comparative context of drawings by apes, children and the insane,” or “Any art made by persons who, in Westerners’ metaphorical imagery of the Family of Man, are regarded with affection as baby brothers, genetically related and genealogically equal but not yet trained to repress their natural urges in conformance with the rules of civilized behavior,” or more succinctly: “The art of peoples whose in-home languages are not normally taught for credit in universities.”)

Still and all, it’s hard to deny the thrall that whatever one wants to call the sort of artifacts warehoused, for example, in Paris’s Musee de l’Homme around the turn of the last century had on artists like Picasso and Ernst, whose works graced the covers of the show’s two catalog volumes, alongside strikingly resonant masks by the Kwakiutl of British Columbia and the Tusyan of Upper Volta respectively. Not that either one or the other of those two contemporary artists necessarily had to have seen either of those two other particular works, but rather that there was something crying out to that particular generation of European artists, trying so desperately as they were to wrest themselves out from under the hegemony of more than three centuries of scientistic, positivist, optically based, perspectivally rigorous orthodoxy, something they could draw on for nourishment and succor in the work of civilizations that themselves had never fallen under such an orthodoxy in the first place. Hence, yes, an affinity, somewhat one-sided though it may have been.

Until recently that is, for a new generation of contemporary African artists have lately been returning the favor, albeit tongue wedged firmly in cheek. Thus, for example, Beninese artist Romuald Hazoumé (b. 1962) gleefully revisits the sorts of Gba Gba Ivorian (Baule people) wooden masks so dear to the early European modernists, knowingly recasting the same sorts of faces out of such contemporary junkyard detritus as plastic jerrycans, twisty scrub-brushes, and discarded earphones. Modernist affinities, indeed.

NEXT ISSUE: PART THREE — CO-CAUSATION

* * *

STILL ANOTHER FOOTNOTE (AND WE DO MEAN STILL) FROM A BOOK YOU DON’T HAVE TO HAVE READ (OR EVER READ) AND FOR THAT MATTER CAN’T HAVE YET BECAUSE THE BOOK WON’T EVEN BE OUT TILL LATER THIS SPRING

Footnote 17

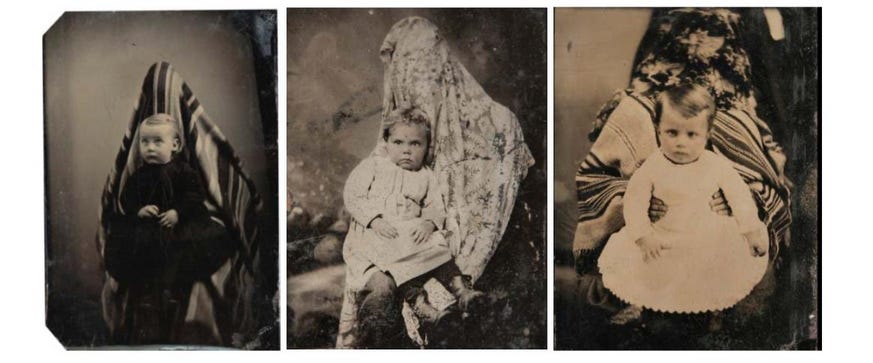

Consider, in the context of the stock-still forty-second exposures subjects were required to endure across the wet collodion photographic portraiture process during the middle of the nineteenth century, the haunting, haunted motif of the disappeared mothers in Victorian photographs of their babies, as elucidated recently in Alicia Yin Chang and Erin Barnett’s fine piece in The Atlantic, how the mothers were forced to cradle their kids in a stiff embrace so that the squirming babes would indeed remain motionless for the entire duration of the plate’s exposure, but at the same time were required to hide themselves since this wasn't supposed to be a photo of the two of them, only of the family’s prized newborn.

Talk about enduring duration...

Or perhaps more to the point, consider the remarkably hushed stillness of one of the most famous of the earliest chemical photographs, Louis Daguerre’s “Boulevard du Temple” from 1838.

Stilled, perhaps, because the vista feels so uncannily empty, and we, its viewers, get to experience the meditative silence the image engenders. And yet historians have determined, thanks to the shadows cast by the trees, that in fact the image would have had to have been taken around eight in the morning, at the very height of the Parisian rush hour, when the scene would actually have been quite noisy indeed, all bustling with foot and carriage traffic, and the only reason we don’t see any of that in the finished plate is that it all got washed out owing to the ten-minute length of the photo’s exposure (wherein anything moving simply disappeared). Indeed, look more closely, and the two discernible figures there in the lower lefthand corner, the bootblack and his client, would have had to have been staged and ordered to stand still for the full ten minutes in order for them to appear at all.

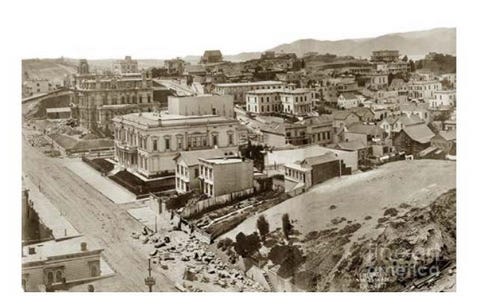

In this context, Eadweard Muybridge, forty years later, becomes a fascinating character, since having noticed the same phenomenon, during the early 1870s, in his famous panoramas of San Francisco (a virtual ghost town by the look of them, entirely devoid of moving people),

he had gone on, within a few years, to mobilize a whole series of technical innovations, many of them of his own invention (others having to do with new filmstock emulsions that could accommodate ever shorter exposures) to make movement itself his subject,

in the process playing a key role in the coming invention of motion pictures (see Rebecca Solnit’s magisterial exposition of the whole saga in her marvelous River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West).

Almost exactly a hundred years after that, in 1976, a twenty-eight-year-old Japanese-born-and-raised artist named Hiroshi Sugimoto, recent graduate of the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena and newly established in New York, had a vision. As he would subsequently recall,

I'm a habitual self-interlocutor. One evening while taking photographs at the American Museum of Natural History, I [asked myself]: ‘Suppose you shoot a whole movie in a single frame?’ [...] Immediately I began experimenting in order to realize this vision. One afternoon I walked into a cheap cinema in the East Village with a large-format camera. As soon as the movie started, I fixed the shutter at a wide-open aperture. When the movie finished two hours later, I clicked the shutter closed. That evening I developed the film, and my vision exploded behind my eyes.

In effect, the result evinced the very obverse of the effect Daguerre and Muybridge had encountered with their ghost town cityscapes. With them, anybody moving in the frame during the necessarily long exposures simply disappeared (and the pavement, say, behind them shone through, precisely because it hadn’t been moving). But here, because of all the movement inherent in the moving picture, every single square inch of the screen at some point registered stark white, if only briefly, such that the negative plate in Sugimoto’s camera eventually burned clean through across the length of its two-hour exposure. And the result looked startlingly like the sort of thing such California Light and Space masters as Douglas Wheeler, James Turrell, and Robert Irwin were straining toward in real life around the same time.

Now, for the longest time, during the nineteen-sixties and seventies, Robert Irwin, subject of my own first (Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, 1982, expanded 2nd edition 2009), had forbidden the photographing of any of his works because, as he put it, “photography captures everything the work is not about and nothing that it is, which is to say that it can only capture image and never presence.” Presence, there, being the key term, and a distinctly curious one at that. Because “presence,” counterintuitively, is in some ways the very opposite of “present.” Thus, for example, to be present is to be right here right now, to exist, that is, in the absolute immediate present, the infinitesimally compressed synapse between past and future, like a snapshot, whereas presence is more like being here now, an extended posture maintained across a prolonged moment, precisely like the duration Berkman locates, by contrast, in the stilled act of posing required with a wet collodion print or a daguerreotype.

* * *

AND SPEAKING OF DURATION

INDEX SPLENDORUM: THREE CROOKS

Shorts, that is, by the inimitable Daniel Crooks, a Kiwi video artist (b 1973) based in Melbourne, Australia. who, over the past couple decades has been perpetrating some of the most sensuous, time-stretched and mindbending innovations in the medium. It’s a small-scale ongoing art scandal that he has yet to attain any gallery representation or distribution here in the United States, but that’s no reason for us here at the Wondercabinet to deprive ourselves of the sublime pleasure of his ensorcelations. (Especially in the context of the Footnote above on the experience of time in photography.) Back in 2013, I had occasion to converse with Mr. Crooks at some length for the catalog of an early mid-career retrospective at the Samstag Museum of Art in Adelaide, and if you’d like to get a better sense of what he’s up to in these three samples of his work, that might be the place to go. We may yet avail ourselves of further such examples of Crooks’s work in future instances of the Index. But for the time being (the being of time being of the essence here), there’s this:

1) Train No. 1 (2002-13). An early instance of Crooks’s manipulations of train-time in a sort of doff to perhaps the earliest such manipulation in the history of cinema (that of the Lumiere Brothers in 1896).

2) Imaginary Object No. 3 (2007). If you’d like to know how the hell he managed to contrive this effect, here’s a clue: all it is, basically, is a time-sliced portrait of a crumpled sheet of white paper (for more on which, see the catalog conversation referenced above).

3) Static #19 (2012). The pieces in Crooks’s Statics series tend to start out as simple video snippets he prized along the way across his world travels: a species of street photography. The subtitle of this one (“shibuya Rorschach”) will give you some idea where he prized the source material, though of course that was only the beginning.

As I say, more to come, here in the Index Splendorum at the Wondercabinet.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

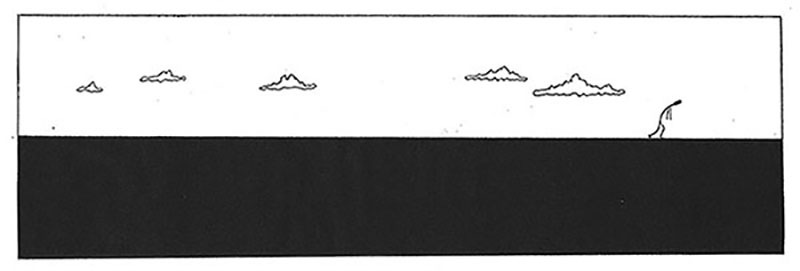

Cartoons by David Stanford.

***

NEXT ISSUE

Part Three of the TAXONOMY OF CONVERGENCES (or: How We Try to Understand the World), specifically cataloguing instances of Co-Causation (which is to say everything from Fractalization and Branching Structures through Simultaneity, Identity, Zeitgeist, and Memes)—featuring the likes of make-believe mountains, vampires, floaters, Newton and Darwin, naked ladies in the moonlight, and naked moles in their tunnels); a conversation with the young Chilean novelist Benjamin Labatut about When We Cease to Understand the World; rampaging ice crystals; and more…