March 13, 2025 : Wondercab Not-So-Mini (87A)

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Taking off from where we left off last week—and hardly a mini-Cabinet, as it happens, this time out!—the second and final part of our director’s cut of Ren’s profile of the by turns fabled and notorious West Coast assemblage master Ed Kienholz, segments of which first ran in the New Yorker in May 1996 at the time of a full-career retrospective overview of his and his wife Nancy’s lifework at the Whitney in New York.

***

The Main Event

Last week we followed Ed Kienholz from his early days on a hardscrabble Depression-era farm in western Washington state (born 1927) through various peregrinations that presently brought him to Los Angeles in the mid-fifties where he hooked up with various Beat types and both produced art work of his own and, in collaboration with the legendary Walter Hopps, helped foment an entire art scene, grouped around the seminal Ferus gallery, which they founded. His own work grew more and more challenging, both formally (from wall-mounted to stand-alone to entire room-sized installations) and thematically (taking on many of the most hot-button issues of the day), culminating in a mid-career retrospective that almost got the newly reconfigured Los Angeles Museum of Art shut down on its first contemporary show, in 1966. With two young kids from a failed third marriage in tow, he kept generating one sensational assemblage tableau after another, several of the signature pieces of sixties American art (“Roxys,” “The State Hospital,” “Back Seat Dodge ’38,” “The Illegal Operation,” “The Beanery,” and the like), but as his fourth marriage was now coming to an end, he found himself at a crossroads.

Of Cars and Carcasses:

A Profile of artist Ed and Nancy Kienholz

on the occasion of his 1996 retrospective at the Whitney,

segments of which originally ran in The New Yorker, May 5, 1996

PART TWO

Lyn and Ed split up in 1972, and he met Nancy a few months later. At the time he was working on "The Middle Islands," his most ferociously despairing take yet on the woe that is in marriage. He seamlessly enlisted her into its ongoing fabrication, so it's not as though she didn't realize what she was getting herself into from the start.

Who knows why this union eventually took when all the others hadn't. Maybe Ed had just mellowed. Maybe it was, as some of their friends surmised, that for the first time Ed had met a woman as strong and independent and gruff and prickly as he was, a woman (as one of his friends put it) "who simply wouldn't take his shit." Nancy's father [Tom Reddin] had been the chief of police—a relatively decent aberration, incidentally, in the otherwise unbroken string of mad-dog authoritarians who occupied that post in L.A. for decades—but her mother was quite accomplished as well, with an entirely independent career as a realtor, and hence something of a role model; in addition, Nancy had had to learn to hold her own in the face of two older brothers. She was twenty-nine when she and Ed met (he was forty-five), herself the survivor of an earlier disastrous marriage raising a young daughter on her own while at the same time running a successful enterprise growing out of her own earlier work as a court stenographer (work in which context she'd honed a remarkable capacity for focus and concentration). Ed was obviously taken with the whole package.

On the other hand, he was wary, too, and it was only gradually that he came to trust in her and the relationship completely. Once he did so—it would be years later—he felt he had to tell her. "We were in Berlin," Nancy recalled for me recently, "working in the studio, and I think I was reaching over to hang a hammer or something, Ed was at his chair, rocking, as he usually did, just watching me, when suddenly he announced, 'Okay, Nancy, that's it.' What's it, Ed—I asked him. 'I give up.' You give up what, Ed? 'That's it. I'm your hunk of meat.' I said, 'Okay, Ed, that's fine,' and kept on working, but for him it seemed important to have established that."

Being someone's hunk of meat was Ed's idea of romance.

They were in Germany at the time because within six months of their original meeting, Ed had been invited to spend a season in Berlin as a guest of the city's DAAD visiting international artists program. They took to the heady, somewhat artificially hyped cultural energy of the city so well, and to the place's own sense of impacted history, that they decided to establish an outpost there. (In addition, they very quickly developed a following of enthusiastic fellow artists and collectors.) Thereafter, they began spending half of each year in Berlin—in spacious though quickly overflowing studio and living quarters on Meinekestrasse, just off the Kurfurstendamm—and the other half in Idaho. (They always made it a point to be back in Hope in time for the Fourth of July festivities in neighboring Clark's Fork.) L.A., they abandoned completely.

Over the years, I visited them in Berlin on several occasions, which reminds me: Ed could be an incredible bastard. One time, for instance, early on, I was meeting up with a friend in Berlin and we were preparing to take that night's train into Poland (this was in the early days of Solidarity). We were both freelancing in those days and hence traveling extremely frugally. But when Ed heard we were about to head into the dread, drab East, he insisted on taking us out for one last good meal at this favorite Konditorei of his just down the way. There he magnanimously insisted that we sample this veal and that salmon, this sausage and that duck, and oh, we just had to try the house schnapps, and don't dare pass up this incredible dessert. At the end of the meal, when the waiter arrived with the bill, he immediately grabbed it, studied it for a few moments, and then declared, 'Okay, let's see, that'll be $110 from you, Carl, and $95 from Weschler..." The effect was so unnerving—that was about all the money we had budgeted between us for the entire trip—and the ensuing discomfiture so prolonged (Ed never broke a grin), that that's all I remember of the incident. Did we end up having to pay? Did Ed relent? Was it a joke? I just don't recall. I phoned my friend Carl to tap his memory, but he couldn't be sure either. "We did end up boarding the train that night," he surmised tentatively. "He must have paid." Probably. But Ed loved playing that kind of mind-game. He'd probably have said he was just teaching us some kind of lesson. Ed loved teaching people lessons like that.

(Another time I'd been sent to Idaho to prepare the catalog essay for an upcoming museum show. With Kienholz pieces, it often paid to know the story behind them—or anyway his version of their inner narrative. Not that such accounts exhausted the works' possibilities, by any means. It was precisely part of their power that they often lapped well beyond his immediate intentions. But still, the stories helped. So I was there for four days, and each time I tried to broach the subject he'd say, Naah, see, I'd asked the question the wrong way, or he wasn't in the mood, or was why I being so obtuse? He was having a grand old time. At times like that, I'd often recall Irving Blum's exasperated quip about his onetime Ferus associate: "The thing you have to realize about Kienholz," he'd sigh, "is that a quarter turn of the screw and we could have had Adolf Hitler all over again! Just a quarter turn of the screw!" Finally, the last afternoon, a terrific wind storm kicked up out on the lake at which point Ed cheerfully announced, "Let's go fishing!" He took me out on his boat—the lake had turned incredibly choppy, the boat was tossing all about—and in no time I was green with nausea and, frankly, with terror. At which point Ed expansively proceeded to lavish me with all the tales and information I'd spent the previous days trying to ferret out. There was no way I could note any of it down—I could barely focus on what he was saying, let alone grasp a pad or pen. After about half an hour, immensely pleased with himself, Ed steered us back to the dock, and I quickly went off to my guest quarters to be sick. Later that evening, somewhat recovered, I tried to revisit some of the stories he'd earlier broached, out there on the tossing waters, but he just looked at me dumbfounded: what was my problem? He'd already answered all those questions. I suppose, once again, he was only just teaching me some lesson.)

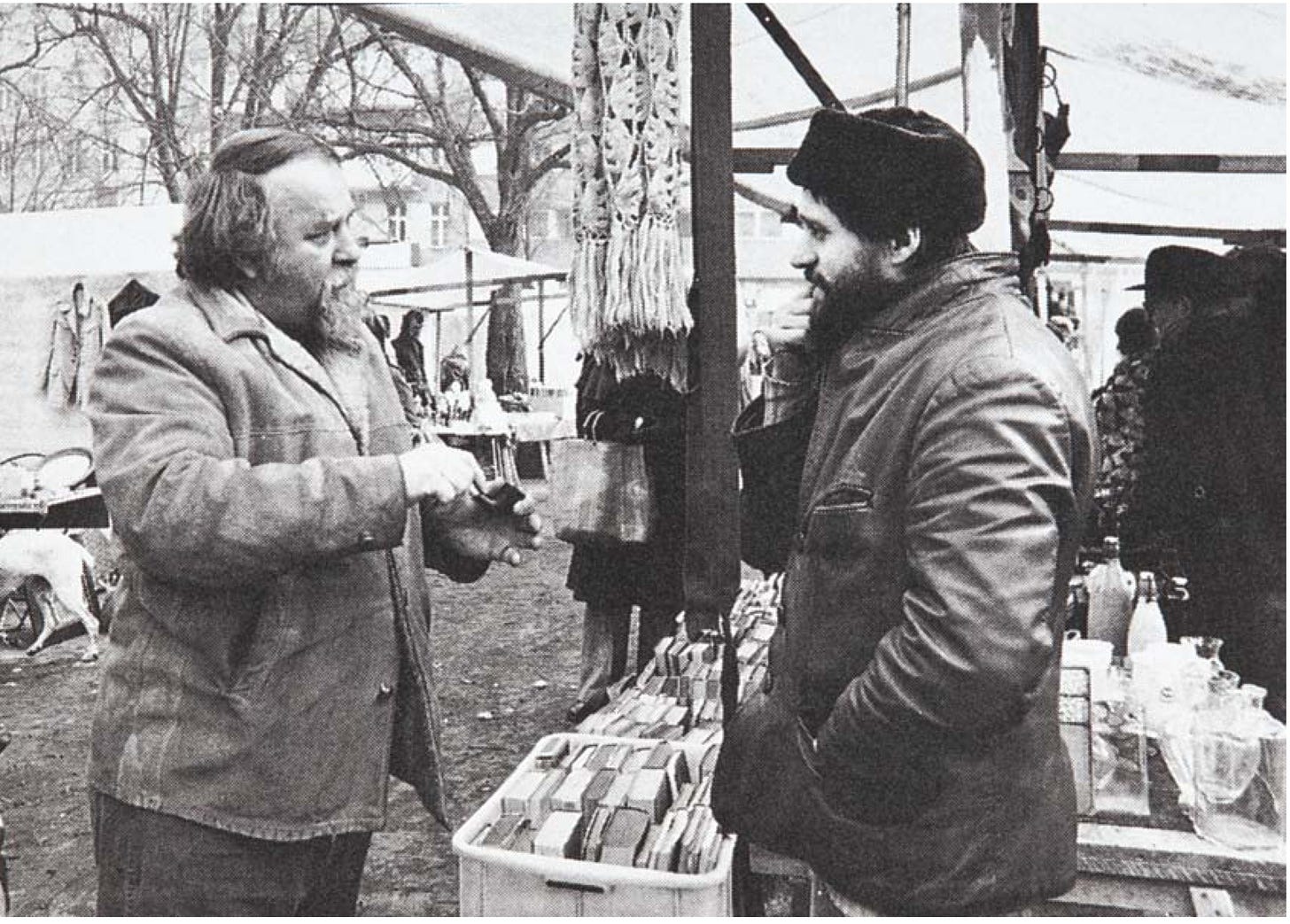

But at other times Ed could be incredibly generous. In fact, often, just hanging around with him—the zest with which he'd ford into the world, the kinds of things he'd notice—was a continuously fizzing delight. One day in Berlin he invited me along on a trek through the local flea market.

By this point he must have been making his annual half-yearly pilgrimages to Berlin for well over a decade (they'd continue through 1989, when, to his and Nancy's mind, the mood of the reunified city, after a few brief months of elation, changed decisively for the worse, and they instead began wintering in Houston), but he'd nevertheless somehow managed to remain entirely innocent of any acquaintance with the German language. He marched intently down the aisles, a thick wad of bills in his pocket, pausing occasionally to consider this picture frame or that military medallion, this photo album or that radio carcass. He seemed to be particularly drawn to the old, black-garbed widows with their pathetic wartime hordes spread out across their ratty green blankets. "How much this?" he'd demand of one of them, holding up a short stack of tattered photos. "Funfsehn," the matron would pronounce with bored finality, to which Ed was likely to bark back, "Fuck funfsehn! FIVE!"—usually carrying the day. (Sometimes, afterward, pleased at having prevailed in the game, he'd nod over to Nancy and have her pass the old lady a fifty-mark note after we'd left the scene.)

It was incredible the sheer density of narrative Ed could glean—or maybe, rather, generate?—from such artifacts. "Look at this one here," he'd say, handing me a fairly standard-issue photograph of a stiffly posed young Nazi soldier. "See how it must have been taken before he left for the front—look at the condition of the uniform—but then, clearly, he did leave, and this photo would have belonged to his girlfriend or maybe his mother. She would have picked it up daily—see there, in the corner, how her right thumb gradually wore away the image—and held it up close to her face—see, how the trace of her close breathing discolored the area here right around his face—and then probably he was killed: I mean, those look like tear stains to me along the side of the image." Could be: sure sounded plausible.

*

If the Kienholzes' German fans were initially delighted and even found themselves confirmed and in some ways validated by the couple's mordantly caustic take on the American reality, they were perhaps decidedly less so once Ed and Nancy began turning their sights on Germany's own dark legacy. The Kienholzes were bowled over by their first exposure to Wagner and immediately began incorporating his music into a series of pieces keyed around Nazi and Teutonic iconography. In another sequence, they deployed antique Volksempfänger radios of the sort Hitler had ordered provisioned into every German home (this in ironic counterpoint to the series Ed had earlier launched around American television coverage of, say, the Vietnam War).

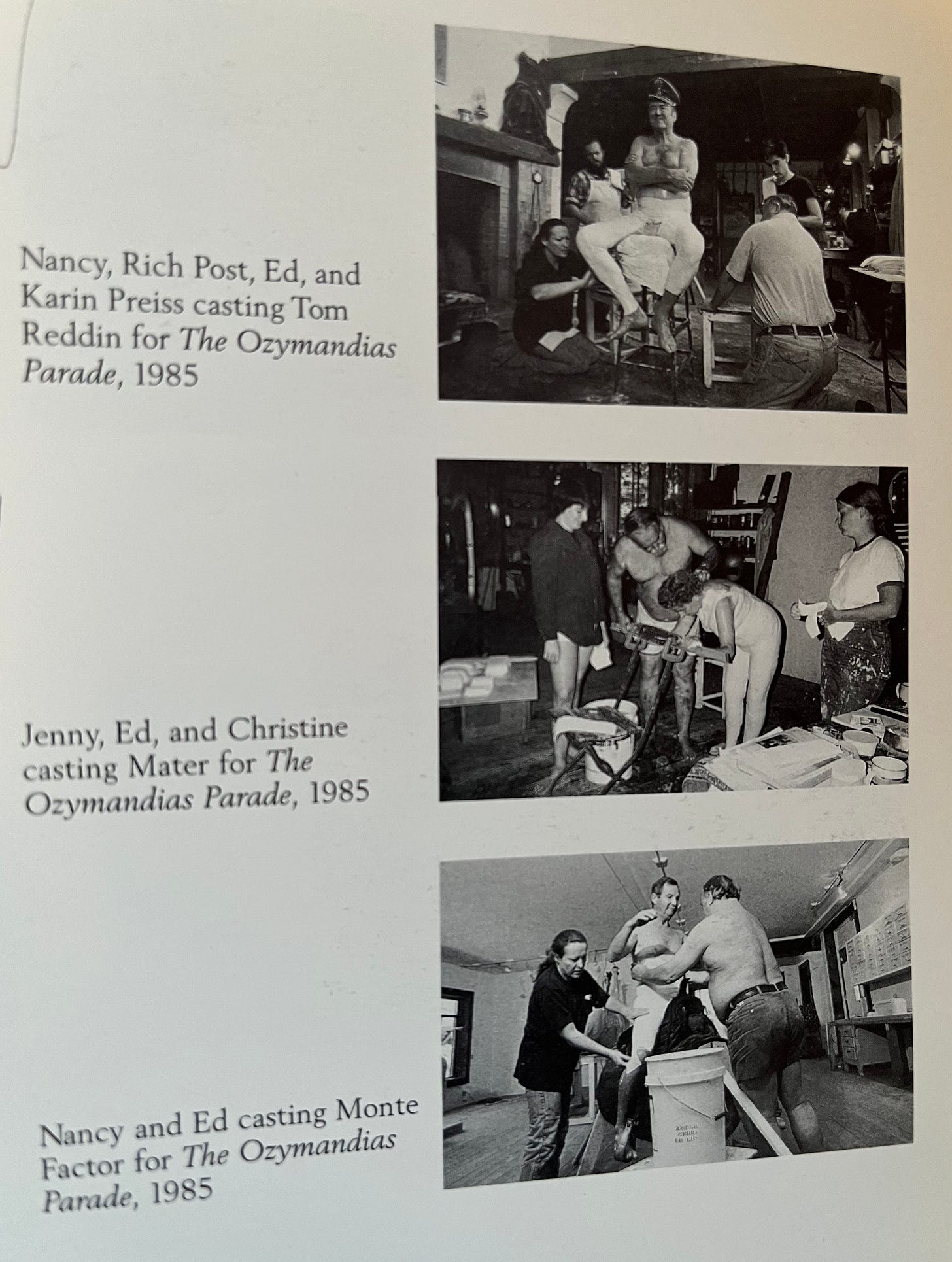

Meanwhile, the two of them were now truly working as a team. There were some who'd initially found Ed's unilateral declaration of the work's coauthorship a bit strained, in fact paradoxically even a touch sexist in a patronizing sort of way. Back in 1976, when I'd first visited the Kienholz compound in Idaho, there was already no doubt that Nancy had become a huge force in Ed's worklife, but primarily as archivist, photographer and general manager of the atelier. By the end of the eighties, however, in Berlin, the involvement had clearly deepened. They talked out every piece and seemed to delegate tasks interchangeably—both of them (and for that matter all the kids and the myriad assistants) took part in the plaster-castings and the various scavengerings and the small-scale carpentry, though Ed still oversaw the piece's overall structural undergirding (he remained a phenomenal craftsman) and was usually the one to apply the final unifying splatter of fiberglass through which a piece at last became fully achieved. It was through Nancy, by contrast, that photographs began to be introduced into the work—large-framed head shots, for instance, wedged perpendicularly between the shoulder blades of some of the plaster-cast figures, often to startlingly vivid effect. Thematically, some projects were more Ed's (for instance his European variation on "Roxys," a five-year long project to fashion a densely observed distillation of Amsterdam's red light district, "The Hoerengracht"), while others were more Nancy's ("The Merry-Go-World...," an equally ambitious exploration of the intersection of chance and destiny among people, most of them deeply impoverished, scattered all around the world).

But on a day-to-day basis, their production, like their lives, had become increasingly intertwined. "At one point," Nancy told me, "our principal assistants Tom and Karin Preiss spent a few days shooting a film of the two of us working together in the studio. One day a few weeks later, they brought over a rough-cut of the resultant movie. After they'd finished screening it, we said, 'Great, but what are you going to do for a soundtrack?' That was the soundtrack, they protested—couldn't we hear the clink and clatter of the tools? The point was, we'd simply gotten to the stage where we no longer even needed to talk to each other as we worked—we intuitively knew, each of us, what the other intended and we responded instantaneously to the slightest gesture."

*

I've already mentioned, in passing, some of the vaster projects Ed and Nancy undertook during the years of their collaboration. In this context one might also cite "The Art Show," at first glance a hilarious send-up of a typical opening at some white-cube international art gallery, with eighteen fashionable poseurs scattered about the pristine space in various postures of aesthetic pomposity—their snouts fashioned, variously, out of automotive heating vents or hair-dryer spigots, spewing (at the touch of a floor button) so much multilingual art-critical hot air.

But on closer inspection, something more complicated seems to be going on, for Ed and Nancy in fact cast many of their fondest art world friends, associates, [ADDED COMMA] and patrons in the piece (it's their voices we hear spouting all that nonsense). And beyond that, the Kienholzes have specified that ordinarily, whenever the piece gets displayed, the hosting institution has to allow them to curate a real show of young local talent along the gallery's otherwise empty walls (so that the young artists can attain both a wider exposure and more prestigious entries for their resumes).

Similarly one might consider the equally ambitious though considerably less subtle "Ozymandias Parade," a huge, gaudy, savagely phantasmagoric skewering of the vain excesses of the Reagan years, with Ed's own mother cast as the overburdened taxpayer, staggering under the weight of the puffed-up, medal-strewn general straddling her back, for whom Nancy's father served as the plaster-cast model (as I say, Tom Reddin was not your typical LAPD chief).

*

But to my mind, among the finest achievements of the years of Ed and Nancy's collaboration have been some of the quieter, more intimate tableaux, in particularly a trio of more specifically autobiographical pieces. (When I say "autobiographical," I am referring to Ed's autobiography—pronouns start becoming somewhat problematical in here.)

To begin with there's "Sollie 17," which initially presents itself as a seemingly nondescript corridor inside some urban SRO hotel with one door just slightly ajar. The viewer who hazards a peek inside will find that the door only opens a bit, just enough to afford a vantage onto a haunting triple exposure, three views of a tired old man dressed in baggy briefs, occupying a spare dilapidated room, killing time. First, he is lying on the bed, reading a paperback Western, his hand slipped under the waistband of his underpants, absentmindedly toying with his crotch (in a typical Kienholz touch, the book is entitled "A Handful of Men"). In the second exposure, he is sitting at the side of his bed, playing solitaire, a haggard profile. In the third exposure, he is standing, his back to the viewer, looking out the window at an anonymous cityscape, thinking perhaps about the nothing he's made of his life.

If I call this piece autobiographical, it's in part because Ed repeatedly explained how it was based on a chance incident from his own life, how one day in 1965, while walking through the corridors of the Green Hotel in Pasadena (he happened to be seeking out Marcel Duchamp, as a matter of fact , who was in town for his own career's first retrospective, at the Pasadena Museum under the direction of the irrepressible Walter Hopps), he'd happened upon just such a moment: a door slightly ajar, his own prurient interest provoked, a furtive glance within at a similar old man whose startled expression was at once one of indignation at this violation of privacy and a desperately lonely plea for contact of any kind.

But it's autobiographical even more so because in this, as in many of Kienholz's other evocations of down-and-outers, going back for instance to "The Beanery," what Ed was in fact portraying was a kind of life he could very easily, had things gone only slightly differently, ended up living himself. He once told his son Noah—who told me—how shortly after arriving in L.A., he almost took a job as a gas station attendant (only stopped himself at the last moment), but that had he done so, he was convinced, he too would have eventually found himself holed up in some SRO.

And indeed, Kienholz's art is often quite subversive. In "Sollie 17," for instance, just as you might begin to start feeling yourself superior to the old man in his underwear by the window, you’d notice, almost subconsciously, how because of the way the door is blocked and angled, you are looking at him while scrunched in exactly his hunched posture. Kienholz manages the trick of transmuting his own empathy onto you. He's hot-wired us with his own compassion.

More overtly autobiographical is another work from the same period, currently located on the Whitney's third floor just off to the side of "Sollie": "Portrait of Mother with Past Affixed," a hauntingly intimate reworking of themes first broached in "The Wait."

(In fact, for all the prodigious variety and material profusion of Kienholz's lifework, there are moments when his trajectory seems to me as spare and focused and self-constrained as that of Mondrian: over and over again he—and later he and Nancy together—return to the same few themes, and in fact to one single overriding theme. For over and over again, they are exploring that moment when the despair of absolute solitude is momentarily punctured by the grace of intersubjectivity.)

The Mother in "Portrait of Mother" is Ed's mother: she inhabits a squat rendition of her own lakeside cabin, right near Ed and Nancy's place, and in fact that's a view of Lake Pend Oreille from out her window that one sees photographically reflected in the exterior window as one approaches the piece. As one opens the screen door, there she is, standing there, lost to the world, gazing down upon a large framed baby portrait she is holding in her hands. The baby is in fact herself—little doll hands reach out and up toward the old lady she will become.

Her own face is a photographic portrait, couched in a gold mottled frame: she is, we say, aflame in reminiscence. The photographic view from the interior window behind her is actually that from the Fairfield farmhouse inside which Ed was raised, and in fact she is surrounded by bric-a-brac from that and all the other stages of her life (there's a framed portrait of her husband as a young man on a little ledge, over to the side, and just above it, a mirror which, if the viewer leans in further, turns out to be a fresnel screen beyond which one can dimly make out a photo of her husband as an old man, pathetically crumpled in his wheelchair). This is a portrait of a mother, and yet oddly, the son is nowhere to be seen: except that, in another sense, he stands in the same relation to the entire piece as she does to the baby photoportrait she is holding. It's as if Ed is holding his own life, himself aflame with recollection. And, indeed, there's even a third looped duality, for in order to lend the foreshortened tableau an added depth, Ed and Nancy gave it a mirrored back wall: just as viewers are beginning to contemplate the myriad manifestations of the inexorable passage of time in other people's lives, they may happen to notice themselves there, gawking in the mirror. Zap: hot-wired again!

A few years after the portrait of his mother, Ed embarked on a complementary tribute to his father, or rather, perhaps, to his father's legacy. (Unfortunately, it's not in the Whitney show, for obvious reasons, but it is featured in the catalog.) Fondly recalling the way his father used to take him hunting as a child and taught him how to provision an ample and well-ordered campsite so it felt just like home, Ed proceeded to cast a vast bronze recreation of just such a site, including the rocks around the campfire, the neatly stacked logs, the tree-stump stools, the boxes of canned supplies, the pans and coffeepots, the deer carcass hanging from a tree, the tree itself, and nearby the truck which brought everything there—all of it bronzed and burnished to a richly gleaming finish. (One of Ed's German collectors, who'd acquired a piece of property on Mount Howe right near Ed's place, commissioned Ed and Nancy to realize the piece right there—and it's so heavy it's probably never going anywhere else.)

The main problem in realizing the piece was that Ed's father was no longer alive to be cast. So, instead, Ed had himself cast, and there he sits all alone as an adult, gazing into the fire, his arms stoutly folded over his belly, thinking his thoughts. In one sense the piece might have been called "Portrait of Son with Father Occluded"—in reality, Ed impishly dubbed it "Mine Camp," an obvious reference to Hitler's Mein Kampf, "My Struggle," and it almost makes one wonder—but, no, be still, be still, my Freudian heart.

*

Toward the end of May, 1994, Ed and Nancy closed up their Houston studio and, accompanied by Ed's beloved dog Smash, launched out on the 2300 mile drive back up to Hope. As had become usual with these drives, Nancy clocked about 2100 of the miles, Ed maybe 200 (for all his love of cars and his endless tinkering and noodling and wheeling and dealing, Ed himself hardly ever drove). The last day of the trek, they were heading north out of Riggins, Idaho, snaking along a beautiful winding stretch of two-lane mountain road, about 200 feet above the Salmon River. Nancy was taking it easy, enjoying the view, when from around an oncoming curve came hurtling two mammoth semitrucks, the one passing the other. There was nothing to be done—it was sheer rockface to one side, precipitous cliff-fall to the other—so Nancy just hit the brakes and they waited. Somehow the trucks blew by, shaving the sideview mirrors. As Nancy tells the story, once she'd started up again, she turned to Ed and mildly observed, "It's a good thing I was driving; you wouldn't have given way to those trucks and we would have had a head-on collision." "No," Ed replied, "if I'd been driving, we wouldn't have been going 45 fucking miles an hour and we'd have been long past this place by now." As Nancy observes, they were both right.

The last day of March, back in Hope now, Ed's dog Smash passed away. (Ed’s mother, incidentally, had died only a year earlier.) The next few days, Ed and Nancy mournfully resumed work on a tableau named "Jody, Jody, Jody," the material distillation of a news story Ed had first encountered years earlier about a little girl who'd been found, abandoned by her drunken parents, terrifiedly clutching the chain link median divider in the middle of one of the fastest stretches of the Grapevine Interstate north of L.A., cars racing by obliviously all about her. That item had been haunting Ed for years (he'd even mentioned it at the time of our oral history—noted how he couldn't get the image out of his mind, felt he needed to render it but couldn't figure out how to do so, thought he might never be able to). At one point, Ed picked up a paint bucket and—this was unusual: Nancy usually did the color painting—gingerly climbed a step-ladder and began applying a gloriously somber sunset to the photomural backdrop.

A few days later, rising from bed in the morning, Ed was felled by a massive heart-attack. He slumped to the floor, still conscious, lucid, calm. Nancy and some of the studio assistants rushed him to the hospital in Sandpoint, an hour up the lake, but he died within hours. While everybody else was coming unglued, Nancy turned to their longtime assistant, Tom Preiss, and simply said, "Get the plaster." She made a death mask on the spot.

A memorial service was convened in Sandpoint four days later, on June 14, and family, friends, neighbors, artists, and art types converged from all over the world. The plaster cast original of Ed, seated, his arms folded stoutly over his belly—the one they'd used to cast the "Mine Camp" bronze—presided over the proceedings from the side at the front of the hall. Several of the congregants rose to speak, but everybody I spoke to about the event seemed to remember Ed’s artist friend and one-time protégé Richard Jackson's comments in particular (they've been included at the end of the Whitney catalog). "Their art is great," Jackson began. "Like Ed, it sat at the table in its underwear and talked about life and anything and everything else." He noted how he himself had first been drawn to the art, but how then he was drawn to Ed himself: "He was my hunting partner. I found an artist who liked to hunt, finally! Not easy in a politically correct time.... But Ed and I hunted together for years at his place in Idaho and my place in California. Hunting camp. One of the greatest places in the world. Hunting camp is such a great place that ol' big-hearted Ed wanted to take everyone hunting; and that's what you and all his friends have been doing for all these years, sitting around hunting camp with Ed: Work hard all day, sit around making plans for tomorrow, joking, playing cards, drinking, eating, discussing life, death, sex, heaven, hell, religion."

Jackson went on to relate how on the drive in from the Spokane airport, he'd taken to thinking about religion. Jesus, what if Ed and he had been wrong in all those conversations and there really was a God and his son was Jesus? Ed was going to be in big trouble. But then again he'd figured, "Ed isn't going to some terrible place that these other people made up." Driving on a bit, he'd noticed how almost all the places in those parts had Indian names. "That's it," he proclaimed, "the Indians! Ed wants to be buried up there by his hunting camp. Ed's going to the happy hunting ground; and believe me, folks, the hunting ground is a happy place. Now I see it pretty good."

Jackson paused for a moment. "Ed," he concluded, "I'm going to hunt around here for a little while longer and when I'm finished, I'll meet you up at the camp."

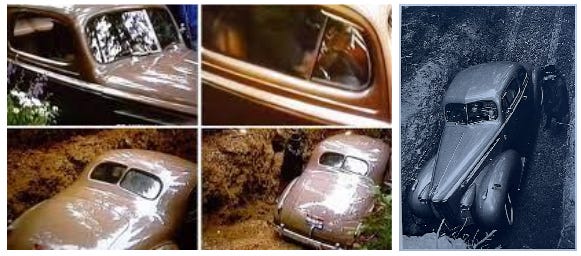

As it happened, Ed himself was outside in the car during all this—the real Ed, his embalmed body, arms folded over the belly, strapped to the passenger seat of the gleaming taupe-colored 1940 Packard coupe in which he'd long let it be known he intended to be buried. (Nancy had grudgingly consented but only on condition that Ed occupy the passenger seat. "I'm not going hurtling through all eternity," she'd notified him sternly, "with you at the wheel, Ed.") Smash's ashes were in an urn in the back.

As the service ended, Ed's son Noah climbed into the Packard to conduct the body on the hour-long drive back along the lakeside and up Howe Mountain to the hunting camp. Noah, an incredibly proficient carpenter and craftsman in his own right (he's currently employed as a studio carpenter in Hollywood), happened to be here in New York recently as part of the crew, "the traveling Kienholz circus," setting up the retrospective, and at one point he took time out to relate the experience to me. "I wasn't letting anybody else take him up there," he said. "And it was an extraordinary experience. I got to have my last words with him there in the car and, believe me, he was absolutely present. It was an incredible gift: sad, strange, somber, serious. But he'd prepared me for that his whole life, and I felt honored. He'd taken me hunting, shown me what a carcass was like, how to gut an animal, how not to be afraid of death. And the whole thing was really funny, too. The last few miles up Howe Mountain, it's one switchback curve after another, and with each one he came lurching for the wheel. I'd stiff him in the ribs, yelling, 'Get back there, you son of a bitch!'" Noah laughed, and sighed, repeating, "It was just an incredible gift."

Noah conveyed the Packard to the lip of the ramp leading into the trench, off to the side of the hunting cabin, that one of the assistants had back-hoed out the night before. The rest of the funeral party now converged, convoy style, on the scene. A few last speeches were made, and Nancy now entered the driver's seat, beside Ed.

She herself took up the story for me a few hours after my conversation with Noah, while stealing her own break from the retrospective's arduous installation. We were standing on the bridge over the Whitney moat—the Back Seat Dodge visible down below to one side, while over on the other, on the first floor wall looming above the cafe, they'd just hung a very recent wall piece entitled "First Car First Date," an unusually sweet and evocative vignette consisting of a lifesize cutaway of the back chassis of a gleaming jalopy, an earnest, clean-scrubbed and black-suited young boy staring fixedly ahead at the wheel, his foreshortened date beside him in a crisp pink skirt, bobby sox and saddle shoes, a corsage on her lap, the lake racing by in the windows beyond. It's evening but still bright, and they're so achingly young: his softball and mitt are stashed on the floor in the back. Nothing terrible is going to happen tonight.

"So," Nancy related, "I got in the driver's seat and turned the key, and of course, the engine wouldn't turn over. Damn Packard: it happened every time. You could never take that car anywhere and expect to make it back. But it's the one he wanted: probably the car he lusted for as a kid. The engine churned and churned and churned—nothing. Finally, they had to push me down the ramp. I set the brake, got out, gave a last look. Ed had a dollar in his pocket; a bottle of good Italian red wine, vintage 1931, by his side; and a deck of cards—enough probably to get him started in the next world. I climbed out of the trench. The radio was playing Ed's favorite big band music.

And now she was quiet for a moment. She noted how someday, when her time comes, she intended to be buried right there beside him. At that moment I happened to be looking at and past her at the wall piece.

First date, I found myself thinking. Last tableau.

* * *

POSTSCRIPT

And indeed, Nancy was buried there on Mount Howe, following her own passing not that long ago, in 2019 (she’d kept the flame aloft for more than twenty years after Ed’s internment). Myself, I’ve continued writing about Ed on and off over the years. You can find another piece (based on the one I wrote for the museum show after that dreadful storm-tossed boat ride) in my Vermeer in Bosnia collection. And yet another one, growing out of his exceptionally prescient, never quite fully realized NonWar Memorial proposal, here. About ten years ago I was getting all set to write an entire book around one of his greatest pieces, “Five Car Stud,” his harrowing 1970 lynching tableau (a gang of hideously masked white men castrating a screaming prone black man for the crime of having taken a white woman, wretching off to the side, out on a date) but it was explained to me, in dead earnest, that this was not the time for a white critic to be writing a book about a white artist’s cultural appropriation of such a theme (despite the fact that the principal theme Ed had been interrogating all along had been whiteness, not blackness), and the unfinished manuscript has stayed in my drawer (maybe I’ll pull it out one of these days and share passages here in the Cabinet). Anyway, as you can imagine, Ed persists in my mind, and perhaps now he will in yours, too, just as he does to this day, in painted plaster cast form, mock-glowering, off to the side in his former studio back beyond Hope.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

what an incredible series of articles. this is the best piece I have consumed from the Wondercabinet. I have always loved Kienholz and ranked him in the top five of contemporary artists. this carries him to the top of the stack. thank you.