June 20, 2024 : Issue #70

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

With Ren on the road, a guest wonderer, Alexander Nemerov, gets lost in the woods.

* * *

The Main Event

A Guest Wonderer:

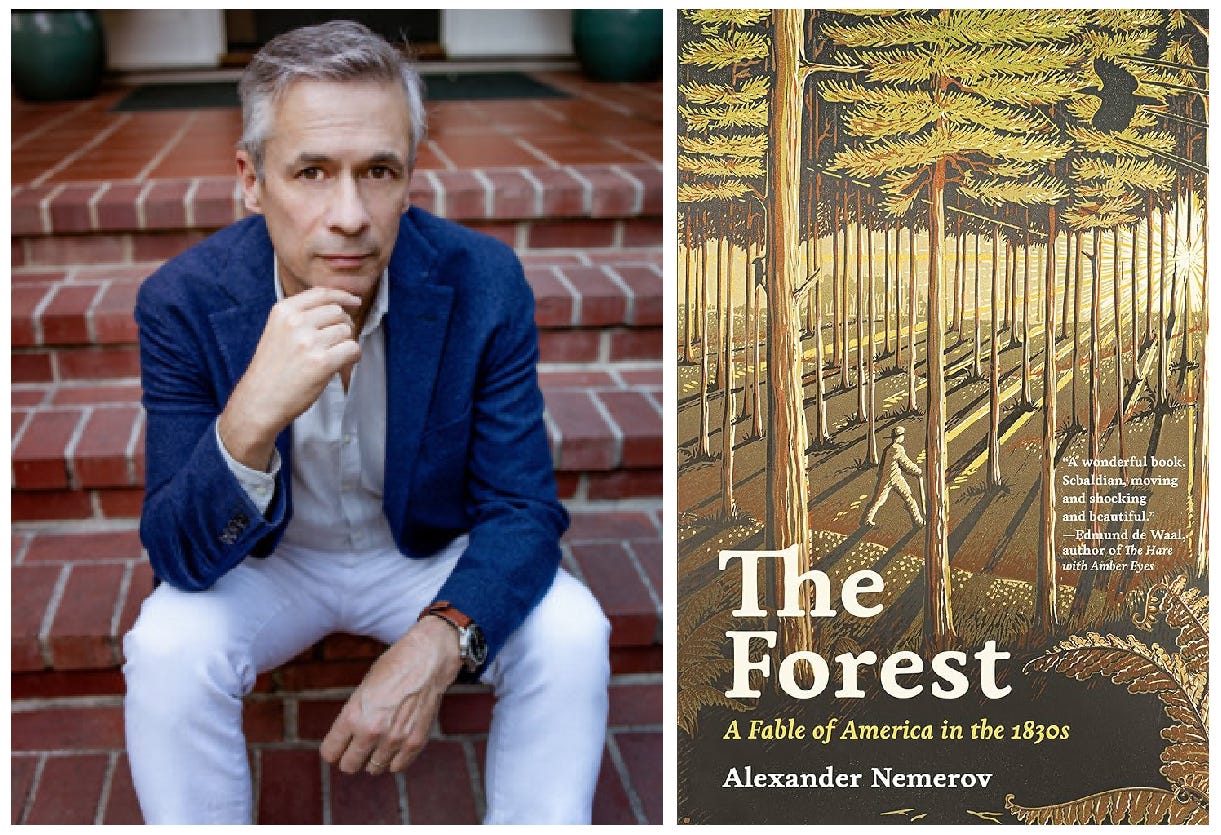

Alexander Nemerov, Deep in the Woods

As Ren was still going to be traveling this week, he asked his friend Alexander Nemerov, the Carl and Marilyn Thoma Provostial Professor in the Arts and Humanities at Stanford University, whether he might be willing to stand in for a spell at the helm of the Cabinet—or more specifically whether he’d be willing to let us here at the Cabinet excerpt a full chapter from his own marvelous recent compendium of the miscellaneous diverse, The Forest: A Fable of America in the 1830s. Drawn from the Andrew Mellon lectures the good professor gave at the National Gallery in Washington, the book decants a veritable cataract of stories, reveries, conjectures, fabulations verging at moments on confabulation—deeply researched and then searched still deeper—all around the theme of the crucial hinge decade of the 1830s when the great American continental forest was giving way to the suddenly exponentially proliferating Westward expansion of the settler populations. Everyone, but everyone, seems to be passing through. The prose is lyric verging on the poetical, nonfiction verging on the speculative, but each of these often fantastical-seeming stories ends up getting buttressed by a veritable grove of references and cross-references in a Notes section at the back of the book, such that by the end who knows, or would necessarily want to know. Thus, for example, this elegant shapeshifter of a tale from about one hundred pages in, about yet another delirious dabbler into the miscellaneous diverse, seeming forefather of us all:

Encounter in a Black Locust Grove

Constantine Rafinesque was an oddity at Transylvania University. He was strange anywhere, but at this new frontier institution in Lexington, Kentucky, he stood out especially. With his large bald head and corpulent, stooping figure, he was “physically shrewlike to a degree that fascinates.” His ill-fitting clothes seemed assigned to him at random; his ignorance of basic domestic economy—rituals of cleanliness, for example—was complete. His logical but antiquated mind was like the ruins of the old frontier station upon which modernizing Lexington was built: an archaic fortress facing all directions at once, bristling with defenses, a fantastic design of obsolete purpose in a new age.

At Transylvania, Rafinesque was a double stranger. He was a native Turk and the only naturalist in a school devoted to training Presbyterian ministers. The university president, a Unitarian, was a friend, but the board of trustees thought so little of Rafinesque that they paid him no salary except room and board and candles and wood for his fireplace, and even then they complained that his candle usage was too high. Maybe they had it against him because he was always submitting lists of demands and requests. Querulous and high-strung, the man was an outpost unto himself.

To subsist, he needed to attract paying students to his lectures, which fortunately he was able to do. He spoke about everything. A former student fondly recalled his lectures on ants, on their culture and history and society, their “lawyers, doctors, generals, and privates,” how after their great battles they have “physicians and nurses” to care for the wounded.

A fair specimen of his teaching, his papers in the short-lived Western Review and Miscellaneous Magazine addressed the salivation of the horse, the oil of the pumpkin seed, and the Milky Way. At a time when universities were developing specializations and departments of expertise, Rafinesque arrived in Lexington as a know-it-all, among the last human beings aspiring to understand the entire universe. A short list of the fields to which he contributed includes botany, horticulture, ornithology, ichthyology, mammalogy, entomology, conchology, paleontology, geology, minerology, meteorology, pharmacology, archaeology, astronomy, and herpetology.

A shipwreck off the coast of New London, Connecticut, was what unhinged him. That was back in summer 1815, near the end of a perilous three-month voyage from Palermo to New York. Rafinesque, who grew up in France, had spent a few years as a young man in Pennsylvania and Delaware developing his botanical knowledge, and now en route from Palermo, he was returning to the United States at age thirty-one. But as the ship approached Montauk, it was caught in contrary winds, could not make land, and struck an underwater glacial boulder.

Picked up in a rowboat, Rafinesque watched the ship sink and with it his life’s work: 20,000 herbal specimens, 2,000 maps and drawings, 600,000 specimens of shells. “I had lost everything, my fortune, my cargo, my collections and labors for 20 years past, my books, my manuscripts, my drawings, even my clothes.”

But at that moment something marvelous happened. Call it the birth of Rafinesque the fabulist. Even as he swam from the wreck, he was busy identifying new species of plants and fishes in the water around him—so he claimed. From there it was but a small step to becoming the eccentric naturalist of Kentucky, the one at odds with the trustees and his fellow naturalists. Audubon, on a stay with his eccentric peer, awoke one night to find a naked Rafinesque swinging his guest’s cherished violin at bats that had infested his rooms.

The world for Rafinesque was a kind of plasma, a rolling and shifting of “endless shapes, mutations quick or slow.” As he wrote in his epic twenty-part poem The World; or, Instability, published in 1836, “The great universal law” was the “perpetual mutability in every thing.” Nothing endured and all evolved. Apparently distinct things— trees, rocks, rivers—were all related, reciprocally changing in a great swirl (today we would call it an ecosystem).

God, the “Lord and Leader,” directed it all, but lurking in the shadows, the deity Pan also oversaw Rafinesque’s universe. No ordinary lord, Pan was everything, was everywhere, and not in a terribly pleasant way. The slimy interior of grace, the underbelly and backstory, he made a vast and morphing body: leaves were his shaggy hair; tree bark was his skin. The forest made up his fingers and toes. He burbled in the streams and flowed in the sap, hanging from the trees that comprised his own roots: everything circulated through him, as him, in a vast and mutable fount of creative destruction.

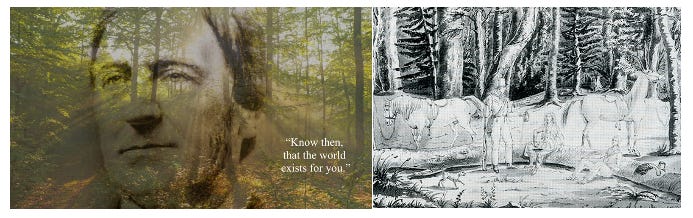

Ralph Waldo Emerson, the era’s most famous pantheist, said it well. “We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree,” he wrote in 1841, “but the whole, of which these are the shining parts, is the soul.”

So did Tocqueville when he noted that Americans regard individual things “only as the several parts of an immense Being.” Pantheism, wrote an American in 1840, is “the admission of everything and the denial of nothing. He has the most accurate knowledge of God who has the most comprehensive knowledge of Nature. . . . God is Nature: Nature is God. . . .My books . . . are studies to reach the One Thing.”

Yet who among Pan’s believers could truly reach the One? Maybe only Rafinesque was right for the job. Only he had the patience and audacity to think the world stick by stick. Studying the frond of herb, holding it to the candlelight, writing his notes in an English that was his fourth or fifth language, he saw an entire forest in a sprig of lichen. The bug that crawled on his filthy cravat, that sizzled in the fire, flamed out as a tiny emissary of the cosmos.

Once he thought he saw Pan. A party of acquaintances had set off for a summer picnic in the woods surrounding Lexington. Forest novices, they carried books, drawing albums, pencils, and sandwiches, planning to make a day of it. Eventually, dripping sweat and not enjoying the trek, they looked for a place to sit down and eat. Finding a fallen tree across their path,

they all sat down at once, and the tree, which proved to be rotten, collapsed beneath them. Out from the hollow emerged frogs, lizards, locusts, katydids, beetles, hornets—every creature in the universe, it seemed. Fleeing, the party lost its way, and only by luck emerged a mile from Lexington a few hours later.

Hearing about the adventure from one of the travelers, Rafinesque recognized the place where they had entered the woods. It was near a stand of ancient oaks, their branches covered in vines, about two miles from a small limestone cave that only hunters and the naturalist himself knew of. He felt that the ruckus of insects swarming and fleeing the picnickers must have happened somewhere near that cave. Why, he could not say exactly. But the comedy of the crushed log, nothing unto itself, seemed to him a sign, a warning, to these idlers to back off a secret place they had come perilously near; and an invitation to him, knower of the All, to proceed.

Following a stream a few hundred yards to one side of the picknickers’ entry point (in their amateur confusion, they had not noticed it), Rafinesque set out for the cave. Before long, he was standing in a grove of black locust trees that he recognized. The trees were blooming, their white drooping flowers exuding a lovely fragrance in the June heat. He looked up, observing how the leaves sprouted in fractal patterns, each one comprising a dozen or so oval segmented leaflets, making a kind of trilobite design. He placed a hand on the nearest tree, stroking its furrowed gray bark, then prepared to venture through the grove to the cave he knew the grove obscured. From his childhood reading—back in Marseilles, where he had taught himself Greek and Latin as a boy—he knew that Pan supposedly lived in a cave, and he now fancied (maybe it was just a whim of that day) that this cave, which he had visited before without noticing anything strange, was the one where the god lived. Before Rafinesque could move farther, however, he became aware that the locust trees around him were shimmering.

They swayed, not in a wind, and not in the shifting light filtering from above, or even from the bees moving busily about the flowers. The trees seemed to emanate an aura—that was how he thought of it afterward—a kind of radiance. A buzzing sound accompanied the light, not the buzz of the bees but more like a sizzling or crackling noise, like a cymbal struck once so that it vibrated with a metallic timbre.

Pan was everywhere, Pan was an “immense Being,” shifting his toe roots and flexing his branch arms—Pan was the whole forest—but he could also conform his shape to any object, make his vastness intimate, and he seemed to be localizing himself just then. After a moment, the vibration and shimmer stopped and Rafinesque left, no longer wishing to look into the cave.

On his way back from the grove to the edge of the woods, he followed the stream. The sound it made on its gentle downhill run was nothing like the ringing noise of the black locust trees. Fragments of the sky appeared sometimes in the pools made by the stream’s pebbles and stones, its lobes of accumulated leaves and mud. Beside one of those pools as he stopped to rest, his round belly heaving as he wiped perspiration from his brow, Rafinesque chanced to look down and thought he saw something. It was not his own reflection, blurred in a passing gurgle of light, but another picture, different from the stream’s intermittent portrayal of the sky. Embedded an inch or two in the silted mud, angled upward against a small stone, a triangular chunk of glass portrayed the overhanging branch of a willow tree. Maybe it was part of some mirror a settler had dropped, or the make-do glass of a more solitary wayfarer, lost on his journey. But there it was, blocking one rivulet of the stream, a glass awaiting its Narcissus. He looked around, then looked back at the broken mirror. He thought about stooping to pick the fragment up, but left it where it was and continued on his way.

It was a shame that Rafinesque was not a good artist (though he imagined his talents differently). His small drawing of the stand of locust trees, now much damaged and barely legible in places because of the foxing of the paper, poorly conveys the otherworldly drama of his experience. Maybe the encounter before the forest cave, let alone the attempt to draw it, made him too agitated to convey what he saw. But for that reason the drawing is inadvertently effective. Quivering in nervous graphite lines, Rafinesque’s trees show the transfiguration in the draftsman, not in what he drew. “An earnest, articulate advocate of nonsense,” a man whose “manic disorder fed on his immense erudition”—it made sense, what a biographer wrote of him. In that drawing titled The Grove of Pan, known to only a few, he created as true a picture of what could not be seen as ever was made.

*

From the Notes section on that chapter at the back of The Forest:

* * *

And by way of a gloss on the foregoing (from a bit further on in the nineteenth century) this reprise of a page from Ren’s Commonplace book:

Nathaniel Hawthorne

From Twenty Days with Julian & Little Bunny By Papa

(edited by the late Paul Auster of aching fond memory)

I have before now experienced that the best way to get a vivid impression and feeling of a landscape is to sit down before it and read, or become otherwise absorbed in thought; for then, when your eyes happen to be attracted to the landscape, you seem to catch Nature at unawares, and see her before she has time to change her aspect. The effect lasts but for a single instant, and passes away almost as soon as you are conscious of it; but it is real for that moment. It is as if you could overhear and understand what the trees are whispering to one another; as if you caught a glimpse of a face unveiled, which veils itself from every willful glance. The mystery is revealed, and, after a breath or two, becomes just as great a mystery as before.

* * *

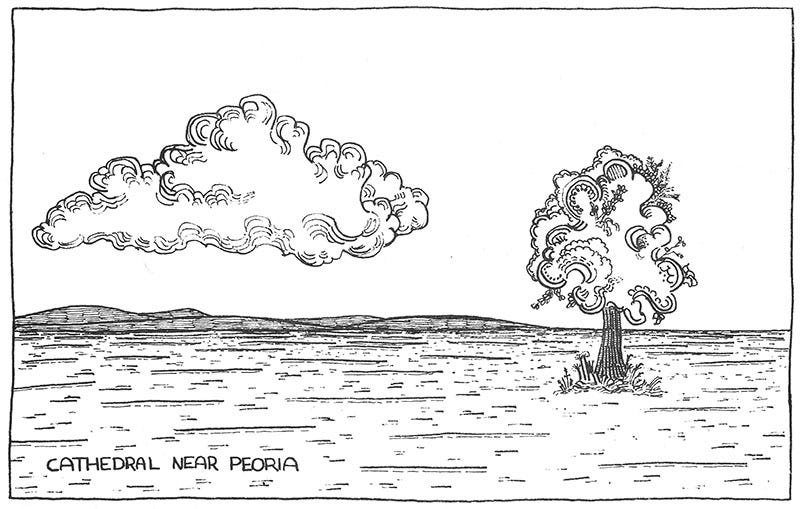

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.