January 20, 2022 : Issue #8

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

Welcome back! This time out, a deep dive into Titian and Ovid on the occasion of the recently concluded show at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. A coda to last issue’s “And Yet…And Yet” cognitive gyre. And Anna Russell graces the INDEX SPLENDORUM with her legendary Wagner Ring Cycle rant…

THIS ISSUE’S MAIN EVENT:

ARTWALK : Titian at the Gardner

I only finally made it up to Boston for the jewelbox Titian show at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in the weeks just before it closed (and the resurgence of Covid in its Omicron variation in turn momentarily closed down the window for such blithe excursions) but I was very glad I did.

The folks at the Gardner had decided to celebrate the unveiling of the exquisite restoration of their own Titian, The Rape of Europa, by bringing together, for the first time since the Renaissance, all six of the so-called “Poesies,” the sequence of grand canvases based on Greek mythology (as filtered through the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses) that the Venetian master (then in his 70s) had created at the behest of the young Spanish prince (soon to be king) Philip II, across the years from 1550 through 1565.

I should perhaps begin by warning you that I am no authority on Titian nor, for what it’s worth, have I particularly concurred with the widespread conviction among art historians and fellow painters that he may have been the greatest painter of all time (if forced to choose, I myself would have plumped for Vermeer or Velasquez). But still, the experience of spending a few hours in that snug room at the Gardner (supplemented as it was by my own frequent recourse to Google and suchlike for quick whiffs of background) was thoroughly invigorating, and I thought I might share some of my own discoveries and potential insights with you here.

The heart of the show is laid out in three thematically twinned pairings, beginning, to one side, with the Danaë of 1553 (the first canvas Titian sent to young Philip back in Madrid) and the Venus and Adonis from the following year.

The Danaë, for its part, must have made quite an impression when it arrived at the resolutely Catholic Spanish court: the sheer acreage of all that female flesh (a veritable Playboy centerfold in an era long before the mass-availability of such cheesecake offerings!). This was only the latest iteration of the theme for Titian—Jupiter ravishing the sequestered young maiden by way of a veritable downpour of gold (in this version with an elderly handmaiden avidly leaning in to snag as many of the raining coins as possible)—but there’s almost a whiff of pandering in the thought of the old master veritably leaning into the young man’s commission in this instance. The thing I couldn’t get over, though, was the decidedly, shall we say, resigned expression on Danaë’s face:

The very opposite (if anything) of avidity (more like, “Really, seriously, now this?”)—a distinct sense, that is, of underwhelment. And that in turn was so striking, because Danaë’s fate, among the cavalcade of such Ovidian ravishings, seems the most distinctly like that of the Virgin Mary (from that other tradition) during the Annunciation, another frequent subject of Titian’s when he was in his better-behaved moments. Indeed the Danaë fell neatly between two of Titian’s most revered renditions of the Annunciation theme, both still ensconced in Venetian churches, the one in the San Rocco (painted in the mid-1530s) and the other in the San Salvador (painted in the early-1560s):

Note in both cases the way the shaft of light piercing down from the dove of the Holy Spirit above rhymes with the Danaë’s shower of gold. Was that Titian himself making the ironic juxtaposition (and if so, to what purpose?), or is it rather us (or anyway me) in all our disenchanted ironicizing modernity?

Or perhaps do I have everything backwards, even asking the question like that? After all, the whole doctrine of the Annunciation (the epiphany of the angel Gabriel before the young Mary), the subsequent insemination of Mary by the Holy Spirit, and the centrality of the whole Virgin Birth narrative are relatively late additions to the Jesus story—not mentioned at all in two of the original gospels (Mark and John), barely so in Matthew (where the angel actually appears to Joseph and not Mary), and only glancingly more so in Luke. Many commentators have suggested that if anything, the whole saga was a late addition to make the Christ story more palatable to the non-Jewish pagans to whom it started being pitched in the years after Paul’s belated arrival on the scene, and for whom such divine ravishings would at any rate have already been familiar (in much the way that for the intellectuals among them, Jesus’s midnight of the soul in the garden of Gethsemane, in which he pleaded with God to “let this cup pass me by”—after all, what cup?—would have been familiar by way of Socrates’s discourse faced with that very cup of hemlock). All of which in turn got me to thinking about W.B. Yeats’s version of the pagan ravishing story in which (quick recourse to Google) for the Holy Spirit dove substitute that Jovian swan: to what extent might the poem’s last lines

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop

have consciously (or even unconsciously) harbored allusions to Mary’s situation?

*

Enough of the Danaë, on to its pendant, right next door, Venus and Adonis from 1554,

which the Titianati inform us allowed the Master an opportunity to show off his extravagant capacities at rendering the female backside with all the voluptuousness that he had lavished on the forward-facing expanses in the preceding canvas. The curators at the Gardner for their part pointed out how strange it was for Titian to have chosen this myth in particular as the subject for what proved to be, that year, a wedding present to the young Philip on the occasion of his (loveless, dynastically mandated) marriage to the considerably older Queen Mary of England. There is doubtless a striking similarity in the faces:

and, along with the Gardner curators on their wall panels, we too can only imagine what Mary made of the canvas, with its middle-aged goddess with her capacious buttocks grasping after the younger man, who seems hell-bent on escaping her clutches so as to be off on his (admittedly ill-fated) hunting expedition.

For that matter, the entire Adonis myth turns out to be a distinctly twisted tale. According to Apollodorus and other such sources (again, thank Google), it turns out that Venus had had quite a history with Adonis’s mother, Myrrha—or actually with her mother Cencheris who had taken to boasting as to how her daughter Myrrha was even more beautiful than Aphrodite/Venus, whereupon, by way of piqued revenge, the goddess cursed the daughter to fall in love with her own father. Long story (viz Ovid), but Myrrha struggled long and valiantly against the cursedly-inflicted obsession though she eventually succumbed and secretly snuck into her father’s bed in the dark of night and seduced him. Come morning, when he in turn pulled aside the curtains to determine the identity of this remarkable intruder, he was horrified to discover that it was his own daughter and almost killed her on the spot. Barely escaping and then wandering the world, pregnant and desolate, for the next several months, she eventually beseeched the gods to take pity and deliver her from this agony, and they did so, transforming her into a myrrh tree (whose aromatic extruding sap evince her tears to this day). Aphrodite herself presently delivered the baby Adonis from the flank of the tree and gave him to Persephone, the goddess of the underworld, to raise. Years later, when the boy had matured into an extraordinarily handsome young man, Aphrodite returned to the underworld to claim him, only Persephone in the meantime had also fallen in love with the exquisite manchild. The two goddesses feuded over him—long story, with Zeus/Jupiter eventually intervening to decree that Adonis would have to spend a third of his life with Persephone, a third with Aphrodite, and the remaining third with whomever he pleased (which turned out to include Apollo, Hercules, and Dionysus). In the meantime he also grew into a singularly gifted hunter, which pissed off Artemis/Diana, virgin goddess among other things of the hunt (who in addition had her own grudges against the profligate Aphrodite) and therefore decided to kill the young man by way of a wild boar’s goring. Venus, wakening one morning by her lover’s side with certain foreknowledge of his imminent fate, endeavored to keep him from leaving, to no avail.

But hey, Happy Wedding!

*

As it happens, Diana/Artemis played a key role as well in both of the Gardner show’s subsequent paired Titian canvases (both of them from the ensuing 1555-9 period).

The mythological basis behind the Diana and Callisto canvas is hardly less up-fucked than that behind the Adonis story; if anything, it’s even more so. In this grim saga, Zeus/Jupiter lusted after one of Diana’s chaste nymphs, the beautiful Callisto, and set about seducing her disguised as Diana herself! (Indeed that seduction was to become the basis for a whole run of pseudo-Lesbian-themed Old Master paintings, by the likes of Rubens and Boucher—countless times—and countless lesser masters, almost always male artists thereby getting double the bang for their specifically gendered gaze while still being able to reassure their almost exclusively male clientele that, no, in fact nothing actually untoward was happening here: neat trick.) At the last moment Jupiter transitioned back into his domineering male self and succeeded in impregnating the poor girl, who for several months thereafter managed to shield her sorry state from Diana and her fellow nymphs by ambling about in a capacious white shift (there is even considerable speculation that this is the actual secret subject of the London National Gallery’s much beloved Rembrandt of the Woman Bathing in a Stream). But eventually the truth could no longer be hidden and her fellow chaste nymphs descended upon Callisto, ripping the shift from her body so that Diana could espy the full weight of the scandal. Which is the moment Titian chose to prize out of Ovid’s rendering of the tale for his canvas:

Enraged at this evident breach of celibacy and brooking no attenuating explanations, the Virgin Goddess summarily expelled Callisto from her court and across the ensuing months the poor girl likewise staggered, abandoned and forlorn, through the wilderness, eventually giving birth to a son, Arcas, only shortly thereafter to suffer the wrath of Hera/Juno who, furious over her earlier dalliance with her husband Jupiter, transmogrified Callisto into a she-bear. The years passed, somehow Arcas survived and grew into a remarkable teenage hunter, who one day caught the trail of a loping she-bear and was on the verge of shooting it clean through with his arrow when Zeus at long last took pity on the situation and transformed the both of them into constellations, Ursus Major and Ursus Minor.

Which is what passes for a happy ending in the fraught world of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

*

Two quick glosses, by way of interlude, before we move on to the next painting:

For those of you who may be starting to find yourselves a bit at sea with regard to all these tangled begettings, Willie Nelson’s concise explication of a more contemporary parallel situation might prove of some solace. (It turns out that Willie’s cover is but one of several of a novelty song written by Dwight Latham and Moe Joffe and first performed by Lonzo and Oscar in 1947. Latham and Moe in turn had based the lyric on a paragraph from Mark Twain’s 1883 piece “Very Closely Related,” in which the humorist claimed to prove how in principle a man could become his own grandfather. Twain for his part likely got the idea from a piece that had been regularly getting recycled in newspapers through most of the nineteenth century though was likely first published as a piece in the Republican Chronicle of Ithaca, New York, back in 1822, that had been out-and-out lifted from an item in that year’s London Literary Gazette, where it had been noted: “This was actually the case with a boy at a school in Norwich.” Geesh, where would we be without Google?)

While for a broader piece of psycho-sociological speculation regarding the taproots of all those genealogical tangles in Greek mythological narratives, see if you can’t track down Philip Slater’s The Glory of Hera: Greek Mythology and the Greek Family (1968), wherein the countercultural critic (author, earlier, of the then-celebrated Pursuit of Loneliness) tries to locate the origins of all that Olympian dysfunction in the pathologies of actual Antique Greek family life which, oy, were really something. Greek women married early, were excluded from public life, and had little legal protection; their husbands, perhaps owing to the way they had been raised, fulfilled their procreative functions but spent as much time as they could outside the household, often in the agora or at the gymnasiums. The semi-abandoned mothers focused perhaps excessive attention on their boy children, who were then snatched out of their care around the age of eight to provide fresh fodder for the gymnasiums (hence all the focus on the respective roles of lover and beloved in such texts as Plato’s Symposium), thereby producing a fresh generation of husbands who would flee their married roles, with daughters getting saddled with parallel if obverse neuroses and resentments. No wonder, Slater suggests, that Greek myths feature so much incest, calamitously inappropriate (if often inadvertent) couplings, daughters lusting after fathers, fathers killing daughters, mothers killing husbands, sons bedding mothers, mothers slaying their kids, etc: Oedipus, Electra, Agamemnon, Achilles, Clytemnestra, Hercules, Jason, Medea, and on and on. And of course the ferociously chaste Artemis and all her cohort. Slater’s analysis may prove overly Freudian for some, though it also raises all sorts of questions as to why that specific set of myths proved so resonant for Freud himself (there in turn-of-the-century Vienna) and for that matter, before that, for Titian and all those other Renaissance masters in their time.

*

Titian once again foregrounded the Virgin Goddess’s fearsome and merciless puritanical zeal in the pendant to that Callisto painting, arrayed right next to it there at the Gardner, his rendition of Ovid’s telling of the terrifying tale of Diana and Acteon.

Or anyway, that’s how everybody (including the Gardner’s own curators) always characterize things.

As it happens, I am quite familiar with Ovid’s version of that particular tale. It featured prominently in the extended final footnote to my Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder book (1995), the last half of which I take the liberty of sampling here:

Actaeon {turned} out to be an enormously important figure in the Elizabethan imagination (as in the wider universe of wonder). The Elizabethans got their Actaeon from Ovid, more specifically from Arthur Golding’s 1567 translation of the Metamorphoses (a text Ezra Pound once praised as “the most beautiful book in the language”). In Golding’s rendition {which appeared a mere decade after Titian’s painting, and therefore might help provide an approximation of how Ovid was experienced during that era}, Actaeon was out hunting in the forest with his hounds when he happened to catch a glimpse of Artemis/Diana (whom Golding also calls Phebe), the beautiful virgin goddess of the moon and of the hunt, bathing in a pool with her nymphs. Drawn by the extraordinary vision, Actaeon approaches silently, stealthily pulling aside the intervening branches—but is seen:

The Damsels at the sight of man quite out of countenance dasht

(Bicause they everichone were bare and naked to the quicke)

(Book III, lines 208-9)

But Phebe (“of personage so comly and so tall / That by the middle of hir necke she overpeered them all”) stands her ground, fiercely defiant:

though she had hir gard

Of Nymphes about hir: yet she turnde hir bodie from him ward.

And casting back an angrie looke, like as she would have sent

An arrow at him had she had hir bow there readie bent,

So raught she water in hir hande and for to wreake the spight

Besprinckled all the heade and face of this unluckie knight,...

(II. 220-25)

At which point the young man’s fate is already sealed:

[She] thus forespake the heavie lot that should upon him light:

Now make thy vaunt among thy Mates, thou sawsts Diana bare.

Tell if thou can: I give thee leave: tell hardily: doe not spare.

This done she makes no further threates, but by and by doth spread

A payre of lively olde Harts hornes upon his sprinckled head.

(II. 226-30)

As yet unknowing, Actaeon scampers off—"trottes," in Golding's beguiling parlance —and it's only when he comes upon a brook and gazes upon his own reflection in the water that...

when he saw his face

And horned temples in the brooke, he would have cryde Alas,

But as for then no kinde of speach out of his lippes could passe.

He sighde and brayde: for that was then the speach that did remaine,

And downe the eyes that were not his, his bitter teares did raine.

Within moments his own hounds have caught the scent of him and he is soon being pursued to his death.

Of course, in our context, we will understand the story of Actaeon's fate for what it is—a wonder narrative and a cautionary tale. {…} A story of possession: Watch out for what you see. (No sooner had Ovid himself completed his Metamorphoses, in A.D. 8, than he himself appears to have inadvertently witnessed something untoward— something sexual? something political? he doesn't say and we will never know—a calamitous misprision for which the great Augustus Caesar condemned him to eke out the remainder of his days in terrible exile along the farthest reaches of the Empire. "O why did I see what I saw?" the poet would be decrying his uncanny fate, a few years later, in Book II of his Tristia. "Actaeon never intended to see Diana naked / but still was torn to bits by his own hounds.") Antlers: from the French antoeil ("in the place of eyes") or the German Augensprosse ("eye-sprouts") {…}

When Chaucer's friend John Gower sang his version of the story, in his Confessio Amantis (also based on Ovid, though two hundred years before Golding), he cast Actaeon's fate as "an ensample touchende of mislok"— a double-pun (touchende implying both “touching” and “the ende of all feeling”) followed by a truly wonderful three-way pun, for, of course, Actaeon had the bad luck to mislook upon Lady Luck. As might anyone risk to do, gazing too long, too helplessly, at Wonder. Not that it wouldn't necessarily be worth it.

All of which, as I say, seems to track with the painting (here reprised),

although Titian already avails himself of a variant source in which rather than leaving matters to Actaeon’s pack of dogs, the Hunt Goddess herself pursues the stag-turned man (you can even see an anticipation of the chase in the background just above Diana’s upraised arm

a dark variation which Titian himself would expand upon a few years later, in 1562, in a sidebar-sequel work, The Death of Actaeon.)

But everybody, and all the commentaries on the painting (at least all of those that I have found) including the Gardner’s own, insist that apart from that detail, Titian is scrupulously following Ovid’s lead, that Actaeon has accidentally pulled aside the branches (and curtain) to reveal Diana naked, surrounded by her nymph-guard, a vision that completely bowls him over, and a misprision that already has the Goddess enraged.

But the thing is, that’s not what’s happening in the painting!

Look again. For starters, follow the sightlines:

The sight of Diana is simply not what has Actaeon so overwhelmed; in fact, he’s not even looking at her. For that matter, what’s the deal with Diana? Those of us who are looking at her can’t help but notice that in this rendition, she’s a pinhead goddess, microcephalic, and this is, as my own old master Harry Berger would have said, conspicuously the case. Titian is one of the greatest painters of all time at the peak of his powers: as every other visage in this entire show demonstrates, he certainly knew how to render a proportionate head, and if he didn’t do so here (or at any rate didn’t correct for the peevish misproportion), it’s because he meant to cast things as he did. Which is to say, to render the goddess in such a way that she’d be a less compelling attraction, and if anything an unattractively pinched and narrowed one at that.

No, Actaeon’s gaze is being drawn somewhere entirely else.

To the girl peering out from behind the pillar, who for her part is gazing out at him, as if equally breathtaken. Indeed, hers is one of the freshest, most vivid, least abashed gazes in all of Renaissance art.

(Especially compared to that of the girl below and to her immediate right, who is all performative high-school faux-sophistication: “My my, hubba hubba, what have we here?”) No, this is one of the great meet-cutes in the history of painting, this is a lightning-bolt, thunderstruck, love-at-first-sight, Romeo-and-Juliet, Tony-and-Maria exchange of glances (and it is as if everything else in the scene has melted to insignificance for the two of them).

Something that the girl below in the shadow of the pink drape has clearly noticed and is in the very midst of tattling about to the Goddess:

“Hey, Mommy, do you see what’s going on over here with Little Sis?”

And indeed She does—and her face has veritably contracted into that tight little fist of fury:

That’s what she’s furious about—not Actaeon’s having seen her, but rather his having aroused such passion in one of her girls. That’s the unforgivable violation as far as the Chaste Goddess is concerned—and it’s entirely Titian’s invention: as far as I (or Google) can tell, there are no classical antecedents, the scenario is entirely Titian’s, one so confoundingly original that hardly anyone since, it would appear, has been able to see it.

Look back again at the girl by the pillar (hers is the only fully lit visage from among any of the nymphs in her grouping, just as Callisto had been the only shadowed one in hers), and look at the pillar:

It’s as if by leaning into the pillar like that she is embracing this sudden stranger (as closely, alas, as she ever will). Notice the pinky finger of her right hand wedged into the crevice between the pillar’s two stones, while the fingers of her left grasp the pillar’s far side just under the capstone, and there’s a pentimento of a still higher grasp just above that (one which Titian has conspicuously chosen not to efface). And then atop all that: the antlered skull. The entire story rolled into one concise passage.

And as I say, decidedly not what we’ve otherwise been told:

*

Before moving on, by way of another brief interlude, and speaking of wildly original takes on Ovidian themes, I just want to commend to your attention (as Google commended to mine) a wild little mash-up improvisation of Rembrandt’s from 1634 (now in the Salm-Salm princely collection in the Wasserburg Anholt in the North-Rhine-Westphalia region of Germany) entitled “Diana Bathing with Her Nymphs with Actaeon and Callisto.” Trust me: it’s all that and more (I especially love Rembrandt’s conception of exasperated Diana in her turban there in the foreground.)

*

Which brings us to the final pairing, and for starters Andromeda and Perseus (1554-6):

Incidentally, Golden Boy Perseus, the virtually archetypal Greek mythological hero—shown here zipping about in midair (powered by the winged-sandals he’d managed to procure in the lead-up to his earlier adventure, the slaying of the Gorgon Medusa) as he prepares to slay the sea monster honing in on our damsel in distress—was himself the son of Danaë, literal spawn of that Jovian shower of gold from the first canvas in the series. Indeed, he seems to be tumbling out of the sky upon that poor sea monster much as gold coins had once showered down upon his mother.

Though Titian was clearly having a grand old time lavishing his High Mannerist virtuosity on the swirling, tumbling confrontation between his Hero and the Sea Monster (as had Ovid before him), it’s clear, if for no other reason than the lighting, that the true subject of this canvas is Andromeda there off to the side in all her chained, threatened and translucent whiteness. That last quality being strange (though by no means atypical, indeed Andromeda’s whiteness is a pervasive trope across the entirety of the Western painting tradition, and it’s incredible how many of the Old Masters took their whack at this story), since both the original myth and Ovid in his rendition are emphatic in describing the maiden as the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, the king and queen of Ethiopia (indeed I was only able to locate one counter-instance, that of Abraham van Diepenbeeck in 1655 at the height of the Dutch slave trade, which of course has its own obverse problems). Granted, Ovid does describe how when Perseus had first spied Andromeda as he coasted by high in the sky above, “He would have thought of Marble stone shee had some image beene / But that her tresses to and fro the whisking winde did blowe” (again, Golding’s translation). But we now know that the Greeks upon whom Ovid was basing his narrative had been in the habit of regularly painting their marble statues in the gaudiest of colors, a fact that has met with considerable consternation and denial from those who insist on the white purity of Greece (‘the cradle of Western civilization”), owing in part to the evident creamy whiteness of those very statues as they present themselves today.

More to the point, though, in terms of the centrality of Andromeda’s place in Titian’s rendering of the story (as in most of the other Old Masters’ versions) is of course the erotic charge of her chained stretched-taut vulnerability, a classic staple of erotic presentation (by male purveyors for male clienteles) to this very day. (Indeed, across his classic 1972 Ways of Seeing television series and its resultant book, John Berger famously demonstrated how so many of the stock poses in contemporary pornographic as well as fashion photography had their origins in such Old Master paintings. And indeed, the framing proportions of a typical Playboy centerfold were virtually identical to those of the Danaë, for example, though in most cases Playboy went for the Andromeda-vertical rather than the Danaë-horizontal presentation.) And note how in this instance, Titian further accentuates the tautness of his Andromeda’s body by rhyming it with the curve of Perseus’s scimitar-like sword on the other side of the canvas.

Andromeda’s incidentally is yet another of these appallingly unfair Greek mythological fates. In her case, once again (as with Adonis’s mother Myrrha’s wrenching-sad story above), she is being punished for her vain mother Cassiopeia’s having boasted that she and her daughter were even more beautiful than the sea-nymph Nereids, which brought the wrath of their patron Poseidon down on the entire Ethiopian kingdom. When King Cepheus consulted an oracle as to how he could appease the sea god’s furor, he was told he’d have to offer up his daughter as a sacrifice by chaining her to a shoreside cliff, which he proceeded to do. Enter Perseus, who happened to be flying by. Completely smitten by his vision of this statuesque girl under impending threat from an approaching sea monster, Perseus immediately descended to earth, though not directly to her; instead he approached her parents on the far shore, who were gazing in horror at their daughter’s imminent fate, and proceeded to haggle: “Now, if I Persey” (in Golding’s version)

sonne of her whome in hir fathers towre

The mightie Jove begat with childe in the shape of a golden showre,

Who cut off Gorgons head bespred with snakish heare,

Perchance should save your daughters life, I think ye should as then

Accept mee for your sonne in lawe before all other men.

Deal? Deal. (Not that Andromeda had any say in the matter.)

I often wonder what the Renaissance Masters themselves made of these stories that they were being encouraged to set to canvas. Obviously there was that sense of pandering to their clientele’s prurient fancies (good lord, the things sold and you couldn’t argue with that). On the other hand, the sheer sense of liberation from the constrictions of the prior generations’ narrow spectrum of acceptable narrative subject matter—the same Old and New Testament stories and a few saints’s narratives, over and over again—must have been truly bracing, as for that matter would have been the new-won freedom to go delving into the anatomical marvels of the human body as such.

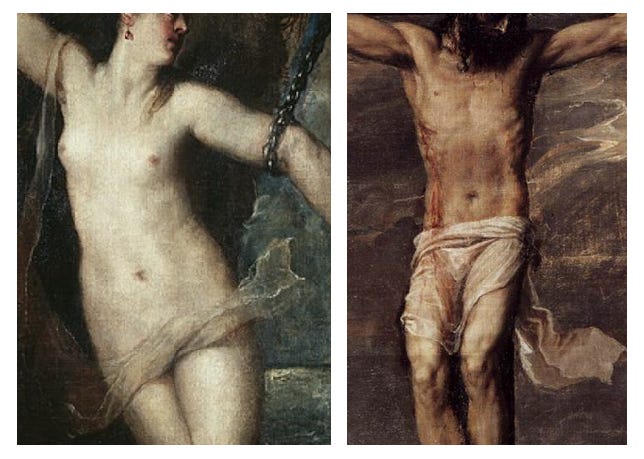

In the case of this canvas in particular, I found myself wondering whether Titian was perhaps alluding to a crossover rhyme between genres, how the way Andromeda was displayed—her arms stretched to the sides, the leftward tilt of her head and the manner in which a bolt of cloth fluttered to the side of her midriff—rhymed so tellingly with such Crucifixion scenes as the one he was working on during those very same years, also destined for the Spanish Court.

Once again, especially when compared with all the other Old Master Andromedas (see the cavalcade of same cited earlier), Titian’s outstretched pose is a fairly unique invention, and one does wonder what’s up with that.

(Speaking of which, take a look at Rembrandt’s meltingly empathic rendition of the same subject, from 1630, a true outlier.)

Finally, before moving on to the last painting in this series, I wanted to call attention to a single detail of this one. I fear that across this series of notes I may not have been calling enough attention to such truly remarkable specific passages, instances indeed of those godlike capacities of Titian’s that so astonished his own contemporaries—in this case (ranged along the distant shore over there to the right of the canvas), that small gathering of desperately concerned onlookers, doubtless including Andromeda’s own parents, each individual somehow fashioned out of a separate distinct flick or two of the Master’s brush:

(How on earth did he pull that off?)

*

Which brings us, at any rate, by way of a commodious vicus of recirculation, back to the occasion for this whole show, the Gardner’s own newly restored Rape of Europa.

Which, for starters, has indeed been gloriously refreshed: the piece just gleams, and that virgin blue sky off to upper left, good lord.

And then, again, the sheer weirdness of the image’s presentation. The uncanniness with which it rhymes with its pendant Andromeda: two imperiled virgins by the sea, their fellows calling out after them haplessly from the distant shore. The way the centered cupid up above echoes Perseus’s tumbling lurch, while his pal, that sly imp down below astride his own bull-fish, simultaneously apes Europa’s awkward straddle and takes advantage of his vantage to stare (a stand in-for the rest of us), unabashedly, right up the girl’s spread thighs, past her exposed breast and on up to that face, half-terrified and half-what-exactly? And then, by contrast, the bull’s soft, gentle mug—innocent guilelessness itself: those placid limpid eyes (“Who, me?”)—the whole effect undercut, of course, by the sheer surging puissance of that near-human, nay, veritably Jovian shoulder. Is the whole thing meant to read as comic, antic, parodic, desperate, tragic, anything beyond sheerly virtuosic?

Part of the tonal confusion may arise from canvas’s title, “The Rape of Europa,” for this is clearly not a rape exactly, or not yet anyway. Though part of that quandary might in turn come down to the English rendering of the original Italian word, “ratto,” which, yes, means rape but also abduction, as in being spirited away, which is more the point of Ovid’s story. Ovid places the action in Sidon, on the Phoenician coast north of today’s Tyre (Lebanon), and Robert Graves, in his compendium Greek Myths, speculates that the original tale may wend its way back to the days when proto-Hellenes and Phoenicians were engaging in tit-for-tat raids. At any rate, Jove spirits Europa to Crete and only reveals himself, as it were, to her there. In this context it’s worth noting that most of the other portrayals of the myth in the Western painterly tradition (and again there are whole slews of them) emphasize the element of transit, and in some of them, if anything, Europa is the one who seems to be steering the bull toward landfall in the west.

Actually, Titian’s version might be the most violent and overtly erotic of the lot.

(For further parsing of the entire situation with Europa’s fate, see this strangely loopy post by an afficionado who writes under the nom de blog “artmoscow.”)

Myself, at any rate, I had the myth wrong. I thought that the spawn of the eventual union of the princess and the god was going to be the Minotaur. But no, actually, the upshot of their conjunction proved to be Minos, who (long story), marrying Pasiphaë, the daughter of the god Helios and the nymph Crete, achieved the throne of the entire island of Crete (thus becoming the putative founder of Minoan civilization with all its famous bull idolatry). At one point Minos pledged to Poseidon that he would sacrifice a particularly gorgeous white bull at his altar but then reneged on the deal, keeping the white bull for himself and offering up a lesser substitute to the Sea God. Poseidon, for his part, was neither fooled nor amused and cursed Minos’s wife Pasiphaë to fall in love with the very bull in question, and it was the spawn of that union that would prove to be the Minotaur, the monster with the body of a man and the head of a bull. (So, technically, Europa was the step-grandmother of the Minotaur.) Minos and Pasiphaë had several children of their own including Ariadne and Androgeous. Minos had his architect Daedalus build a labyrinth within which to imprison the Minotaur and put Ariadne in charge of supervising her half-brother’s imprisonment. Androgeous became a superb athlete, went up to Athens for the Games there, was hugely victorious but then somehow (ending up on the wrong side of an Athenian political squabble) got himself killed. At which point mighty Minos demanded by way of recompense that fourteen Athenian youths, seven boys and seven girls, be ferried back to Crete to be sacrificed to the Minotaur. The young hero Theseus (another Perseus in the making) managed to get included in the shipment, and, arriving at the labyrinth, immediately entranced Ariadne, who gave him the sword with which he could kill her half-brother, and the thread by way of which he would eventually, after killing the Minotaur, be able to find his way out of the labyrinth, at which point the two eloped back to Athens, a polis which would eventually become the veritable font of Western—or as it would come to be known--European civilization.

One wonders if Yeats/Leda-like, Europa, there athwart the back of the Jovian bull, could already see it all coming.

And one wonders, too, what Philip II, like all those Renaissance princes with theirs, made of his own brace of Greek mythological poesies—what Titian, for his own part, expected him to make of them. We know that Philip kept the whole group in a secret room in his private quarters (Spain was still in the grip of the Inquisition, and, as we have seen, Philip himself was a deeply committed Catholic—a man, that is, of decidedly two minds). I suspect that Renaissance painters encouraged Renaissance (post-medieval) sovereigns to think of themselves as quasi-Olympians and as such demigods, to identify that is with their heedless sense of entitlement, privilege, and prerogative.

To a certain extent, perhaps, the painters may have thought of themselves in similar terms: elsewhere I have written about how, a century later, Velasquez, the court-painter to Philip II’s grandson Philip IV, included a tapestry version of Titian’s “Rape of Europa” in the distant backdrop of his own masterful painting of the Arachne story, “The Spinners,” as if, Arachne-like, claiming his own superiority over the prior demigod. And of course Velasquez’s heir Picasso literally cast himself, repeatedly, as a studly Minotaur.

The succession of noblemen collectors into whose hands these poesies gradually accrued (French and then British, in the case of Titian’s Europa) likely imagined themselves rightful heirs to those Renaissance sovereigns and as such Olympians in their own right. And the merchant-collectors of the late nineteenth century who in turn succeeded them definitely did: indeed, dealers like Duveen and Berenson, Hermes-like (Hermes, that is, in his incarnation as the god of thieves), played them off one against the other in vanity-competitions of virtually Olympian intensity.

When, in 1896, Berenson convinced Isabella Stewart Gardner (the daughter of a wealthy linen merchant and wife, soon to be widow, of a shipping and railroad magnate) to purchase the Titian Europa from the Earl of Darnley, it did not go without notice that in so doing she was transporting the bull-borne princess across yet another sea, that Boston itself was fast becoming the new Athens, the new Venice, the new Madrid. If only for a while.

Or so I found myself thinking as I came to the end of the show at the Gardner. Gazing back at the beginning, I could see Danäe there shepherding the visitors into the room, and here now was the splashing bull, nudging us all on out.

* * *

CODA to the last issue’s “And Yet…”

I initially launched out on this Titian piece as if in counterpoint to that ten-year-old “And Yet…And Yet” piece from the Archives with which I led the issue before this one. And notwithstanding the mulish two-mindedness about the rampage of the digital which I gloried in there, this current piece would of course have been completely impossible without lavish recourse to that very digital provenance, both in its crafting and in its dissemination. Such that maybe, on third thought, that’s what I’m in fact about in this whole current Wondercabinet Substack venture: trying to find a way of melding the centered focus of the pre-digital with the vivid promise of the post-.

* * *

Speaking of begettings run amuck

FROM THE INDEX SPLENDORUM

All through those Greek myth summaries, both while I was there at the Gardner and then home, writing up my notes, a high pitched, comically exasperated phrase kept thrumming through my mind, insisting, “I’m not making this up, you know.” It got to be something of an earworm, and I couldn’t figure out where it was coming from, or to what it had first referred. And then suddenly, just now, it came to me. It was the Divine Miss Anna Russell, that operatic comedienne from back in the fifties and sixties who’d sidesplit audiences with her madcap summations of the plot of Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle with all its dueling Nordic demigods in all their zanily incestuous interpenetrations. Many of you will have already heard this LP recording, but some among you may not have, so I thought I’d feather it in here for the delectation of all. Happy listening!

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

An epic footnote delve into the Kabbalah from tsimtsum to tikkun, with side-meanders into the nature of creation (both capitalized and not); Anselm Kiefer, Bruno Schulz, Elie Wiesel, Gershom Scholem…and Larry McMurtry; and speaking of tikkun, a zoom conversation with Rhoda Rosen and members of Chicago’s Red Line Service community on grappling with and engaging the cultural implications of homelessness. And more…

From the cutting room floor:

(For the epigraph to the first chapter of his aforementioned Glory of Hera, on “The Greek Mother-Son Relationship,” Philip Slater mined Thucydides I, 70: “…They are adventurous beyond their power and daring beyond their judgment… Thus they toil on in trouble and danger all the days of their lives, being ever engaged in getting… To describe their character in a word, one might truly say that they were born into the world to take no rest themselves and to give no rest to others.”)

We have not enabled public comments on the site, but welcome any correspondence you may wish to send us directly at: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com . Meanwhile, do subscribe if you haven’t (it’s free!), and please share our existence wherever you can.