February 3, 2022 : Issue #9

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

Welcome! We begin with an epic footnote delve into the Kabbalah, from tsimtsum to Tikkun, with side-meanders into the nature of creation (both capitalized and not); Anselm Kiefer, Bruno Schulz, Elie Wiesel, Gershom Scholem…and Larry McMurtry; speaking of Tikkun, a Zoom conversation with Rhoda Rosen and members of Chicago’s Red Line Service community on grappling with and engaging the cultural implications of homelessness; and Art Spiegelman’s daughter has a question for him…

This Issue’s Main Event:

YET MORE FOOTNOTES FROM A BOOK YOU DON’T HAVE TO HAVE READ (OR EVER READ) AND FOR THAT MATTER CAN’T HAVE YET BECAUSE THE BOOK WON’T EVEN BE OUT TILL THIS SPRING

Footnote #12

Early on in my career at the New Yorker, Mr. Shawn, the magazine’s legendary then-septuagenarian editor, sent me a little note, in his distinctive feathery handwriting, inquiring as to whether I might like trying my hand at contributing fiction. I replied by way of a quickly drafted typed memo (we typed in those days, with keystrokes, onto paper) on why I couldn’t possibly, and a few days later, that memo appeared, pretty much verbatim, anonymously (as all such contributions were in those days), as the lead item in that week’s Notes and Comments section (August 26, 1985), under the rubric, “A young reporter friend writes:” To wit:

Friends of mine sometimes ask me why I don't try my hand at writing a novel. They know that novels are just about all I read, or, at any rate, all I ever talk about, and they wonder why I don't try writing one myself.

Fiction, they reason, should not be so difficult to compose if one already knows how to write nonfiction. It seems to me they ought to be right in that, and yet I can't imagine ever being able to write fiction. This complete absence of even the fantasy of my writing fiction used to trouble me. Or not trouble me, exactly—I used to wonder at it. But I gradually came to see it as one aspect of the constellation of capacities which make it possible for me to write nonfiction. Or, rather, the other way around: the part of my sensibility which I demonstrate in nonfiction makes fiction an impossible mode for me. That's because for me the world is already filled to bursting with interconnections, interrelationships, consequences, and consequences of consequences. The world as it is is overdetermined: the web of all those interrelationships is dense to the point of saturation. That’s what my reporting becomes about: taking any single knot and worrying out the threads, tracing the interconnections, following the mesh through into the wider, outlying mesh, establishing the proper analogies, ferreting out the false strands. If I were somehow to be forced to write a fiction about, say, a make-believe Caribbean island,

I wouldn't know where to put it, because the Caribbean as it is is already full to bursting—there's no room in it for any fictional islands. Dropping one in there would provoke a tidal wave, and all other places would be swept away. I wouldn't be able to invent a fictional New York housewife, because the city as it is is already overcrowded—there are no apartments available, there is no more room in the phone book. (If, by contrast, I were reporting on the life of an actual housewife, all the threads that make up her place in the city would become my subject, and I'd have no end of inspiration, no lack of room. Indeed, room—her specific space, the way the world makes room for her—would be my theme.)

It all reminds me of an exquisite notion advanced long ago by the Kabbalists, the Jewish mystics, and particularly by those who subscribed to the teachings of Isaac Luria, the great, great visionary who was active in Palestine in the mid-sixteenth century. The Lurianic Kabbalists were vexed by the question of how God could have created anything, since He was already everywhere and hence there could have been no room anywhere for His creation. In order to approach this mystery, they conceived the notion of tsimtsum, which means a sort of holding-in of breath.

Luria suggested that at the moment of creation God, in effect, breathed in—He absented Himself; or, rather, He hid Himself; or, rather, He entered into Himself—so as to make room for His creation This tsimtsum has extraordinary implications in Lurianic and post-Lurianic teaching. In a certain sense, the tsimtsum helps account for the distance we feel from God in this fallen world {...}

But I digress. For me, the point here is that the creativity of the fiction writer has always seemed to partake of the mysteries of the First Creation (I realize that this is an oft-broached analogy)—the novelist as creator, his characters as his creatures. (See, for example, Robert Coover’s The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop, in which, for J. Henry Waugh, read Jahweh.) The fictionalist has to be capable of tsimtsum, of breathing in, of allowing—paradoxically, of creating—an empty space in the world, an empty time in which his characters will be able to play out their fates. This is, I suppose, the active form of the “suspension of disbelief.” For some reason, I positively relish suspending my disbelief as long as someone else is casting the bridge over the abyss; I haven’t a clue as to how to fashion, let alone cast, such a bridge myself.

Footnote #13

A vast amount of speculation in the Kabbalistic tradition before Luria had been given over to a meticulous charting of the originary alignment of and relationships between those ten vessels, the Sefirots, from before the Fall, sometimes conceived, in a blending of metaphors, as the primordial Adam or even the Tree of Life itself. Hence Paulus Ricius’s famous woodcut of the Kabbalist lost in thought before the “Portae Lucis” (yet another metaphor: “The Doors of Light”), first published in Augsburg, Germany, in 1516.

The Sefirot constituted the ten emanations, the ten creative forces that mediate between the infinite, inconceivable God, the Ein Sof (the Without-End, the Boundless) and the realms of material creation: the left column, the masculine side as it were, consisting of Binah (Understanding), Din (Justice), and Hod (Glory); with the right side, the more feminine side, consisting in Hokhmah (Wisdom), Hesed (Mercy), and Nezah (Eternity). The middle column, the spine or the trunk, which united the two outlying files, in turn consisted of Keter (the Divine Crown), Tif’eret (Beauty), Yesod (Foundation), and at the very bottom, Shekhinah (the Divine Presence in the World). Indeed, further mixing metaphors, the precise hydraulics between the various stacked vessels was the subject of yet further fevered speculation, with each intervening conduit understood to be serving a very specific function across a system of compounding complexity of which the rendering above barely begins to scratch the surface.

Luria, for his part, working in the wake of the traumatic expulsion of the Jews from Spain during the immediately prior generation, took this relatively static configuration and reimagined it in far more dynamic terms, starting out with that concept of the tsimtsum, by way of which the Ein Sof absented himself from the world in order to make room for Creation, at a certain point during which he directed the overpowering Light of his being into the grid of Sefirots…

Footnote #14

...but, as discussed, something went disastrously wrong, resulting in the shattering of the vessels, the Shevirat Ha-Kelim, represented perhaps most uncannily in our own time, 475 years after Paulus Ricius’s rendering of that old medieval Kabbalist before the Portal of Light, through the vision of another German grand master, in this case Anselm Kiefer’s harrowing 1990 "Bruch der Gefäße” (The Breaking of the Vessels)

with its own wrenching prospective premonition (or alternatively, subliminal retrospective reverberation) of the Nazis’ dread Kristallnacht of November 1938, in some ways the first real intimation of the then-onrushing Holocaust.

Luria’s was essentially a reworking of ancient Gnostic and specifically Manichean doctrines, with the Catastrophe sending shattered shards and droplets (“sparks”) of light crashing into the abyss, which is to say the lifeworld of Creation, our world, the world of human pain—and yet in an inspired twist, Luria’s God was now depicted as himself somehow also wracked by the outcome, human pain being in a certain sense his own pain as well—at any rate he can no longer repair the damage by Himself.

All of this constitutes a novel take on the age-old dilemma of Theodicy: the problem of Evil, or more precisely of how an omniscient, all powerful and good God could ever have allowed Evil into the world. Some have suggested that maybe God simply can’t be all three (He might thus be all powerful and good, but for some reason doesn’t know what’s going on; or He might be both all-knowing and all-powerful, just not good). Other accounts, for example the standard Christian resolution of the dilemma, have had recourse to the notion of free will (God allows evil in the world in the context of lavishing free will upon his human subjects and allowing them to come to their own terms with its temptations)—but what if a once all-powerful and all-knowing and good God has himself been rendered wounded and blinkered by the Fall and hence unable to repair things by himself? This state of affairs would in turn necessitate the centrality of man’s distinct (almost co-equal) role in Tikkun, the restoration of the world.

The preeminent contemporary scholar of the history of Jewish mysticism, Gershom Scholem, placed the Lurianic moment in fascinating context, both retrospectively and prospectively. He sketched out how following the catastrophic failures of a sequence of Jewish revolts against the Romans between 70 and 135 AD and the consequent expulsion of vast numbers of Jews from Palestine, over the ensuing centuries the scattered Jews in their Diaspora contrived two basic ways of reconstituting their Temple in exile: first, the Talmudic, or legalistic, tradition, by way of which the Jews defined their far-flung solidarity through adherence to a strict regime of common rabbinically interpreted and enforced laws (for example, with regard to keeping kosher households, or the group study of common texts in Yeshivahs, and the like)—but also, secondly, by way of a parallel Kabbalistic or mystical tradition, whereby individual Jews through myriad intense devotional practices attempted to constitute their very selves as the Temple incarnate, even if in exile. For almost a millennium and a half, according to Scholem, the two traditions ran in a fruitful, parallel, dialectical relation, but in the wake of the Lurianic revelations, the Kabbalistic movement began to strain against the strictures of the broader Talmudic authorities, in particular by fomenting a sudden upsurge in previously relatively quiescent messianic expectations (after all, the imminent appearance of such a Messiah could be seen as the climactic confirmation of a human-launched campaign of Tikkun), culminating a century later, with the astonishing appearance of Sabbatai Sevi (alternatively denominated “Shabtai Tzvi,” or with any number of variant spellings), a wildly charismatic (apparently Tourettic) Smyrna-born Kabbalist who, at the approach of the year 1666 (a date freighted with apocalyptic millennial expectations on the part of all sorts of denominations throughout Europe) declared himself the Jewish Messiah, quickly gathering up the fervent devotion of hundreds of thousands of beleaguered Jews throughout the continent, to the horror of most of their rabbinical authorities (especially so because he declared that what with his arrival, Jews no longer needed to follow their strictures, no longer for example needed to keep Kosher). Sevi proceeded to march on Constantinople where he predicted he would confirm his messianic vocation by convincing the Ottoman Sultan to give Palestine back to the world’s Jews (the far-flung anticipatory frenzy reaching a fever pitch)—but in the event, the would-be Messiah was arrested at the city’s gates, thrown into jail, only to emerge several months later, having converted to Islam!

The shock of this development of course shattered the movement: many reverted shamefacedly to conventional orthodoxy; others lost their faith altogether; but surprisingly, not a few retained their conviction that Sevi had in fact been the Messiah, reasoning that he had selflessly descended into the deepest darkest abyss of apostasy so as to gather up the remaining shards and droplets of light scattered about down there, and that he would soon be returning triumphant (a conviction not altogether that different, when you think about it, from how the earliest Christians responded to what was after all the actual execution of their leader). Scholem, for his part, compiled a thousand-page chronicle of the entire affair, arguably his magnum opus.

Generations passed, many of these believers grew increasingly antinomian and politically radical, including a sect of Frankists (followers of Jacob Frank, a subsequent Polish Jewish messianic claimant), a yet more fervently transgressive group who arguably helped seed the ground for the French Revolution in 1789. (See the similarly epic magnum opus of the recent Polish Nobel Laureate Olga Tokarczuk, The Books of Jacob, first published in Warsaw in 2014 but only released in English translation just a few weeks ago.) And many of those, or anyway their heirs, found their way beyond that into the rationalist assimilationist movements of the nineteenth century (people who, for example, still considered themselves somehow Jewish even though they no longer felt the need to keep Kosher). Which may help explain, or so Scholem suggests, why one keeps finding thoroughly assimilated, in some cases almost completely deracinated Jews—Marx, Freud, Kafka, even Einstein to an extent—in turn fashioning elaborate secularized versions of essentially Kabbalistic notions of fall and redemption.

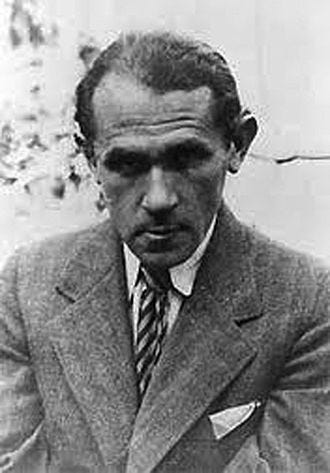

Not to mention the sublime artist-writer Bruno Schulz, author of The Street of the Crocodiles and Sanitorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, who was killed in 1942 by a passing Gestapo officer while trudging home, a loaf of bread tucked under his arm, in his provincial hometown of Drohobych—immediate victim, it seems, of a petty rivalry between Nazi officers, one of whom was getting back at another who had been protecting Schulz as he required him to paint fairy tales scenes across the walls of his five-year-old son’s bedroom. As a result, the magnum opus Schulz had been laboring over, a novel called The Messiah, was also lost, like so many of Schulz’s fellow citizens, in the Holocaust. Though some holdouts prefer to think that, as with that lost manuscript’s namesake, we all just find ourselves pining for the text’s eventual reappearance. The spectre of Schulz’s lost novel has in any case exerted a powerful thrall over subsequent literature, showing up almost simultaneously in 1986-7 as a central motive element in both Cynthia Ozick’s The Messiah of Stockholm and David Grossman’s See Under Love. As for the boy’s bedroom walls with their fairy tale renderings, also long thought lost, they were in fact rediscovered in 2009, launching a fierce polemic as to where they should be preserved—in Poland (Drohobych had been part of Poland before the war, and Schulz is considered one of the greatest stylists of the Polish language) or in the Ukraine (where Drohobych was now situated and whose greatest laureate Schulz had also long been considered)—a polemic settled by default when a group of experts from Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum, swooped in and pried the images off the walls, largely wrecking them in the process, and spirited the splintered remains back to Israel (in a latter day echo, some couldn’t help but note, of the originary Kabbalistic Shattering of the Vessels).

Meanwhile, in the wake of the desolation occasioned by the False Messiah’s apostasy, another strand of the Kabbalistic tradition had reformed as the Hassidic movement, built around its own series of charismatic leaders with their own intensified notions of man’s relation to the divine, often transmitting their doctrines by way of vividly rendered tales and parables. As, for example, in one such story conveyed by Elie Wiesel in his 1978 collection One Generation After:

Having concluded that human suffering was beyond endurance, a certain Rebbe went up to heaven and knocked at the Messiah’s gate. “Why are you taking so long?” he asked him. “Don’t you know mankind is expecting you?”

“It’s not me they are expecting,” answered the Messiah. “Some are waiting for good health and riches. Others for serenity and knowledge. Or peace in the home and happiness. No, it’s not me they are awaiting.”

At this point, they say, the Rebbe lost patience and cried: “So be it! If you have but one face, may it remain in shadow! If you cannot help men, all men, resolve their problems, all their problems, even the most insignificant, then stay where you are, as you are. If you still have not guessed that you are bread for the hungry, a voice for the old man without heirs, sleep for those who dread night, if you have not understood all this and more: that every wait is a wait for you, then you are telling the truth: indeed, it is not you that mankind is waiting for.”

The Rebbe came back to earth, gathered his disciples and forbade them to despair: “And now,” he said, “the true waiting begins.”

(Which in turn may help explain Kafka’s cryptic comment that “the Messiah will come only when he is no longer needed; he will come only on the day after his arrival; he will not come on the last day but on the very last.” Kafka, who also once responded to a question, “What have I in common with the Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself, and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe.” In itself one of the most quintessentially Jewish things ever said, particularly within the stream of thoroughly assimilated Jewry to which he himself belonged.)

But not all such Hassidic tales were so confrontational. Thus Elie Wiesel once again, in a strangely lighter (or shall we say, less despairing) vein, from the preface to his book The Gates of the Forest:

When the great Rabbi Israel Baal Shem-Tov

Saw misfortune threatening the Jews

It was his custom

To go into a certain part of the forest to meditate.

There he would light a fire,

Say a special prayer,

And the miracle would be accomplished

And the misfortune averted.Later when his disciple,

The celebrated Magid of Mezritch,

Had occasion, for the same reason,

To intercede with heaven,

He would go to the same place in the forest

And say: “Master of the Universe, listen!

I do not know how to light the fire,

But I am still able to say the prayer.”

And again the miracle would be accomplished.Still later,

Rabbi Moshe-Leib of Sasov,

In order to save his people once more,

Would go into the forest and say:

“I do not know how to light the fire,

I do not know the prayer,

But I know the place

And this must be sufficient.”

It was sufficient and the miracle was accomplished.Then it fell to Rabbi Israel of Rizhyn

To overcome misfortune.

Sitting in his armchair, his head in his hands,

He spoke to God: “I am unable to light the fire

And I do not know the prayer;

I cannot even find the place in the forest.

All I can do is to tell the story,

And this must be sufficient.”

And it was sufficient.

To which, Wiesel adds the summary gloss: “God made man because he loves stories.” And—as Voltaire, Mark Twain, and Frank Wedekind, among others, would no doubt have insisted—just as surely the other way around.

But oy, that Elie Wiesel: The man could be so annoying, so cringingly and crushingly sanctimonious and overbearing, but damn, the guy sure could tell a good story.

Which in turn brings me round to the late great Larry McMurtry. Remember that note I wrote to Mr Shawn about how I couldn’t write fiction (see Footnote #12 above). Actually there was a whole second half to that typewritten memo of mine which Shawn also included in that week’s Notes and Comments, which I take the liberty of including here in commemoration of the Texas master’s recent passing), to wit:

All these thoughts have come to the fore for me just now on account of my recent summer reading. Larry McMurtry, one of my favorite novelists, has a big new novel out, the epic that all of us McMurtry fans have been hearing rumors about for years. It's called Lonesome Dove; it basically concerns a cattle drive from southernmost Texas all the way to the highlands of Montana back in the late 1870s, around the time Montana was beginning to be made safe for settling (or, actually, as the novel reveals, it was at precisely this time that brash exploits by characters such as these were going to make that north country safe for settling, although it sure as hell wasn't yet); and it's a wonderful book. McMurtry's ongoing capacity for fashioning fully living characters—filled with contradictions and teeming with fellow-feeling—is in full bloom here; he's created dozens of them, and he's managed to keep them all vividly distinct. Reading the book, one begins to think of the novelist himself as a trail driver, guiding and prodding his characters along: some tarry, others bolt and, after a long, meandering chase, have to be herded back into the main herd; others fall out and stay behind; still others just die off. Why does he, I marvel—how can he—keep driving them along like that, from the lazy, languid Rio Grande cusp of Chapter 1 to the awesome Montana highlands past page 800? In many ways, McMurtry strikes me as not unlike his character Captain Call, the leader of the drive, who just does it and keeps on doing it as, one by one, all conceivable motivations and rationales slip away. And yet, unlike Call, McMurtry seems overflowing with empathy for every one of his creatures—a lavishment of love which makes his ability, his negative capability, to then just let them go (after lavishing so much compassion in the fashioning of them), to just let them drift into ever more terrible demises—all the more remarkable.

I have so many questions to ask McMurtry about how he does it. But he wouldn't much cotton to my coming around and asking them. I know: I tried once. McMurtry lives part of the time in Washington DC these days, where he runs a rare-book emporium in Georgetown. I remember, about five years ago, arriving by train at Union Station and looking up the store's name in the phone book and calling the number from a payphone and asking the answering male voice whether Mr. McMurtry was in and being told yes, it was he speaking. I said, “Great, don't move, I'll be right over.” I hailed a taxi and was there in less than ten minutes. I entered the shop, found him behind his desk, and started pouring forth praise and appreciation and heartfelt readerly thanks and then headed into my few questions. And all the while he stared back at me, completely indifferent. The sheer extent of his indifference was terrifying. I ended up stammering some sort of gaga apology and bolting.

A few weeks ago, two of McMurtry’s more recent novels were reissued in paperback—timed, I suppose, to coincide with the hardcover publication of Lonesome Dove. They included new prefaces, and these prefaces helped me to appreciate the icy reluctance to talk about his own writing with which he greeted me that day. “I rarely think of my own books, once I finish them,” he records in the preface to Cadillac Jack, “and don't welcome the opportunity, much less the necessity, of thinking about them. The moving finger writes, and keeps moving; thinking about them while I'm writing them is often hard enough.” In the preface to The Desert Rose he plays a variation on this theme: “Once I finish a book, it vanishes from my mental picture as rapidly as the road runner in the cartoon. I don't expect to see it or think about it again for a decade or so, if ever.” But those prefaces nevertheless suggest the contours of some answers to the sorts of questions I wanted to ask: questions about creators and creatures, free will and determinism—finally, I guess, about grace. At one point, he writes about the way one of his characters, Harmony, in The Desert Rose, “graced” his life during the time he was writing about her. (That’s a good, an exact, word; I remember how she graced my life, too, as I read about her.) “In my own practice,” he notes, “writing fiction has always seemed a semiconscious activity. I concentrate so hard on visualizing my characters that my actual surroundings blur. My characters seem to be speeding through their lives—I have to type unflaggingly in order to keep them in sight.” Later, he records that he was “rather sorry,” as he finished the book’s composition, when Harmony “strolled out of hearing.”

Characters stroll out of hearing all the time in Lonesome Dove, and strolling's not the half of it. They lurch, career, and smash out of hearing: they get snake-bit, drowned, hanged, gangrened, struck by lightning, bow-and-arrowed. The untamed West of Lonesome Dove is a tremendously dangerous wilderness. McMurtry offers a luminous epigraph to his epic, some lines from T.K. Whipple’s Study Out The Land: “All America lies at the end of the wilderness road, and our past is not a dead past, but still lives in us. Our forefathers had civilization inside themselves, the wild outside. We live in the civilization they created, but within us the wilderness still lingers. What they dreamed, we live, and what they lived, we dream.” It occurs to me that as a reader I stand in somewhat the same relationship to McMurtry as that which Whipple suggests obtains between us and our forebears. Here McMurtry has gone and done it—created this tremendous epic massif. All the while, as he was doing it, he must have been envisioning us someday reading his epic; and now we, as we read it—or, anyway, I, as I read it—try to imagine what it was like for him doing it, making it, living through the writing of it. And the thing I keep wondering about, in my clumsy, gawky fashion, is this: Did he, too, feel the sorrow, the poignant melancholy, that he engenders in us as, one by one, he disposed of those, his beloved characters; or was he able merely to glory in the craft of it, the polish, the shine? Are they—his characters—more or less real for him than they are for us?

Oooh boy, how did we end up here? Talk about digressions on top of digressions (Turtles, I tell you, turtles, all the way down). And yet I can’t help feeling that all of it—all of it—still has something to do with Shimmel Zohar, or so I anyway pray that I will yet be able to convince you, my Dear Sorely Put-Upon Reader.

* * *

Speaking of Tikkun…

A-V ROOM

Rhoda Rosen and members of Chicago’s Red Line Service community grapple with and engage the cultural implications of homelessness

In the brutal winter of 2013, curator Rhoda Rosen and artist Billy McGuiness, living at opposite ends of the 26-mile-long north-south Red Line of Chicago’s metro service, launched a practice of preparing home-cooked meals every Saturday night and going out to the blustery platforms at one end of the line or the other to share them (with proper tablecloths, plates and silverware) with some of the people experiencing homelessness who had taken to living out their nights on the metro trains and were being forced to disembark between rides. From that initial action grew a widening community and the insight that in addition to their being houseless, people experiencing homelessness were living out a sort of exile from the city’s vital cultural life. The community themselves set out to remedy that situation, systematically challenging Chicago’s cultural institutions to make room and provision for them. In addition, several of the community members turned out to be artists, poets, and other sorts of cultural workers, or else started seeing such possibilities in themselves, and they began deploying their talents.

Rhoda Rosen, reared and educated in South Africa (BA and MA in art history from the University of the Witwaterstrand in Johannesburg and PhD from the University of Illinois in Chicago) went on to serve for more than a decade as the director of the Spertus Museum in Chicago (that city’s Jewish museum). In addition to teaching the theory and practice of curation at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she is currently president of the board of Red Line Service, which, in the words of the Chicago Tribune’s Lori Waxman “makes the kind of critical, visionary art that is engaged in world building, in rendering palpable the world we want to live in,” and she and I were joined in this Zoom conversation (part of the series I curated for last year’s Venice Architecture Biennale) by several of her fellow community members from Red Line Service.

For more on Red Line Service (and to contribute to their extraordinary work) go here.

* * *

A FURTHER LEAF FROM MY COMMONPLACE BOOK:

As many of you will be aware, Art Spiegelman, the creator, among many other landmark works, of Maus, his seminal two-volume graphic novel of the Holocaust, has recently found himself an object of controversy, vilification, and celebration, owing to the 10-0 vote of Tennessee’s McMinn County board of education to ban inclusion of the Maus books in the district’s libraries and curricula on account of their recourse—I kid you not—to curse words and nudity. (McMinn, incidentally, is one county over from Rhea, whose seat Dayton was the site of the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial.) Spiegelman’s wry and measured response to the developments over CNN and other such venues naturally sparked an extraordinary surge in demand for the books (and as of this writing, Amazon is temporarily sold out)…

The whole grim brouhaha put me in mind of what happened when the Maus books were first issued in Polish translation, a scandale I will return to in a bit more detail in our next issue.

Meanwhile, it also put me in mind of a conversation with his then-eleven-year-old daughter Nadja (this would have been almost twenty-five years ago, around 1998; I know because our daughters are almost the same age) that Spiegelman once related to me and that I included at the time in my Commonplace book. To wit:

Eleven-year-old Nadja: “Hey, Papa, what’s worse than finding a worm in your apple?”

Art: “Gee, honey, I don’t know. Finding half a worm?”

Nadja (exasperated): “No, Papa! The Holocaust!”

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

P.S. CONVERGENCE

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Following on from this issue’s brush with Kabbalah, a look at the long tail of Alchemy; anticipating this week’s Tennessee imbroglio, what happened when Art Spiegelman’s Maus finally appeared in Polish translation; Piotr Bikont channels Ad Reinhardt; and more…

We have not enabled public comments on the site, but welcome any correspondence you may wish to send us directly at: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com . Meanwhile, do subscribe if you haven’t (it’s free!), and please share our existence wherever you can.