February 17, 2022 : Issue #10

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

Hello again. This time, two efforts following on from pieces in the last issue. To begin with, “Lead into Gold,” on the age-old human quest to turn nothing into something, from the alchemical philosopher’s stone through more recent subprime loans (and on into yet more recent cryptocurrencies and NFTs, whatever the hell they are). And then following on from Art Spiegelman’s recent travails in Tennessee, an earlier convergence of Jews, Poles and Pigs; and Piotr Bikont riffing off Ad Reinhardt… Party on.

***

This Issue’s MAIN EVENT:

STILL ANOTHER FOOTNOTE FROM A BOOK YOU DON’T HAVE TO HAVE READ (OR EVER READ) AND FOR THAT MATTER CAN’T HAVE YET BECAUSE THE BOOK WON’T EVEN BE OUT TILL THIS SPRING

{And indeed the very next footnote following on from the three included in the last issue of this fortnightly, which had all dealt in general with matters Kabbalistic, and in particular with the Jewish Mystical Lurianic conception of the moment of Creation, when G-d shone the full power of his being into an intricately aligned array of glass vessels, the Sefirot, which were intended to embody all the aspects of his nature as they would be required to play out in the created world, only something went disastrously wrong and the vessels shattered and…well, go back to that issue to see what happened next. Meanwhile, following on from those endnotes, there’s this:}

Footnote #15

Striking in turn how many of the Kabbalists at the same time dabbled in alchemy—and how similar the hydraulics of the sefirot array could at times seem to the convoluted splay of vessels and tubes in the traditional alchemist’s laboratory, which in turn gets referenced in Zohar’s wet-collodion print of his own contemporary, the alchemist’s worthy heir, that Chemist Developing Non-Humorous Laughing Gas {for a sense of which, see the detail at the top of this post}.

All of which (you know me, or at any rate ought to be beginning to by now) reminds me of a season just over ten years ago that I spent as a visiting scholar at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. Early on I was invited over to meet with Jim Wood, the president and the chief executive of the entire Getty operation, whom I’d known in an earlier incarnation when he was directing the Art Institute of Chicago while I happened to be artistic-directoring the Chicago Humanities Festival. At our brief meeting there in his office, Wood explained that he had been particularly happy to see that I’d be spending a season at the Institute, since he was hoping that I might in passing come up with suggestions for shaking the whole Getty operation out of its perhaps overly staid and disciplinarily siloed approach to its activities.

And so I kept the suggestion in the back of my mind during the ensuing weeks as I pursued my own scholarly intentions, and one day, it happened that I was lunching with one of the rare-book archivists of the marvelously endowed Institute collection, and between us we got to blue-skying the possibilities of a show I’d been fantasizing about (do you guys happen to have this, I’d ask the librarian, and invariably he’d say, Yes, we have several of those—and this? But of course, and so forth). I literally sketched the thing out on a napkin as we proceeded, and I presently returned to my office at the Institute and wrote up the proposal. To wit:

Lead into Gold:

Proposal for a little jewel-box exhibit

surveying the Age-Old Quest

To Wrest Something from Nothing,

from the Philosopher’s Stone

through Subprime LoansThe boutique-sized (four-room) show would be called “Lead into Gold” and would track the alchemical passion—from its prehistory in the memory palaces of late antiquity through the Middle Ages

(those elaborate mnemonic techniques whereby monks and clerks stored astonishing amounts of details in their minds by placing them in ever-expanding imaginary structures, forebears, as it were, to the physical wondercabinets of the later medieval period—a sampling of manuscripts depicting the technique would grace a sort of foyer to the exhibition),

into its high classic phase (the show’s first long room) with alchemy as pre-chemistry (with maguses actually trying, that is, to turn physical lead into physical gold, all the beakers and flasks and retorts, etc.) to one side, and astrology as pre-astronomy (the whole deliriously marvelous sixteenth-into-seventeenth centuries) to the other, and

Isaac Newton serving as a key leitmotif figure through the entire show (though starting out here), recast no longer in his role as the first of the moderns so much as “the Last of the Sumerians” (as an astonished John Maynard Keynes dubbed him, upon stumbling on a cache of thousands of pages of his Cambridge forebear’s detailed alchemical notes, not just from his early years before the Principia, but from throughout his entire life!).

The show would then branch off in two directions, in a sort of Y configuration. To one side:

1) The Golden Path, which is to say the growing conviction among maguses and their progeny during the later early-modern period that the point was allegorical, an inducement to soul-work, in which one was called upon to try to refine the leaden parts of oneself into ever more perfect golden forms, hence Faustus and Prospero through Jung, with those magi Leibniz and Newton riffing off Kabbalistic meditations on Infinity and stumbling instead onto the infinitesimal as they invent the Calculus, in turn eventually opening out (by way of Blake) onto all those Sixties versions, the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, etc., which set the stage for the Whole Earth Catalog and all those kid-maguses working in their garages (developing both hardware and software: fashioning the Calculus into material reality) and presently the Web itself (latter day version of those original memory palaces from back in the show’s foyer, writ large);

while, branching off to the other side, we would have:

2) The Leaden Path, in which moneychangers and presently bankers decided to cut to the chase, for, after all, who needed lead and who needed gold and for god’s sake who needed a more perfect soul when you could simply turn any old crap into money (!)—thus, for example, the South Sea Bubble, in which Newton lost the equivalent of a million dollars (whereupon he declared that he could understand the transit of stars but not the madness of men), tulipomania, etc., and thence onward to Freud (rather than Jung) and his conception of “filthy lucre” and George Soros (with his book, The Alchemy of Finance), with the Calculus showing up again across ever more elaborate permutations, leading on through Ponzi and Gecko (by way of Ayn Rand and Alan “The Wizard” Greenspan) to the whole derivatives bubble/tumor, as adumbrated in part by my own main man, the money artist JSG Boggs,

and then on past that to the purest mechanism ever conceived for generating fast money out of crap: meth labs (which deploy exactly but exactly the same equipment as the original alchemists, beakers and flasks and retorts, to accomplish the literal-leaden version of what they were after, the turning of filth into lucre).

And I appended a xerox of that napkin sketch:

A few days later I joined my rare-book archivist friend once again for lunch and showed him my proposal, and he paged through, laughing, seeming to enjoy himself, but he then changed gears, assuring me that there was absolutely no way that such a thing would ever come to pass at the Getty, the idea was way too unorthodox, nice try though. Nevertheless, I decided to pass it by Jim Wood on my way out, so I arranged a second meeting, and much to my delighted surprise, Wood said it all looked good to him and we should see if we couldn’t actually try to pull the thing off . . .

Only, alas, two weeks later, now returned to my New York home, I was to hear of the tragic passing of Jim Wood (in altogether absurd California fashion: a heart-attack alone while ensconced in his hillside home’s sauna)—so that was that, Wood’s passing constituting a terrible loss for the Getty, and on a considerably more incidental scale, the end of that particular fantasy of my own.

Incidentally, JSG Boggs, too, has in the meantime passed away (on January 22, 2017, at age 62); he received extended obituaries in both the New York Times and on the back page of The Economist. I like to think that had he known he was going to be getting that obituary on the back page of The Economist in particular, he’d have died and gone to heaven…which is therefore where I imagine him, smiling down on the rest of us, and on the ensuing comedies of cryptocurrencies and NFTs, knowing full well that had he somehow survived to engage with them, he’d have figured plenty of loopy ways to hijack those markets as well: wresting something from nothing, as he’d have been the first to admit.

* * *

Following on from our last issue’s glance at the recent banning of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, by a ten-to-one vote of Tennessee McMinn County school board (review CNN’s coverage of the imbroglio here), a look back at some of my own dives into earlier, albeit parallel fracases:

From the Archives:

THE BELIEVER, August 14, 2018

A Convergence of Jews, Poles, & Pigs

Featuring Avi Katz, Benjamin Netanyahu, George Orwell, Art Spiegelman, and Piotr Bikont

It’s dangerous nowadays to attempt a two-week news-cleanse, as I intentionally attempted during a recent vacation retreat {in August 2018}: you never know what you’ll have waiting for you when you get back home.

In my own case, what I had waiting, among many many other things, was the story about how Likudist parliamentarians in Jerusalem had passed themselves a new law summarily declaring Israel a “Jewish state,” in one fell swoop thereby demoting the 20% of the country’s citizens who happen to be Arab to a nebulous second-class status, and the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians living under occupation to some sort of status well below that. The law seemed to have been drafted in anxious response to the growing awareness of the fact that, what with negotiations toward a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict stalled if not permanently upended by an endlessly compounding array of government-imposed so-called “facts on the ground,” the Arab portion of the population of those under Israeli suzerainty was fast approaching a majority of all those residing between the Jordanian border and the Mediterranean sea.

Anyway, shortly after the vote, triumphant parliamentarians were photographed by Olivier Fitoussi of the AP celebrating the moment by casting themselves in giddy selfies alongside their smugly self-satisfied leader, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu…

…which in turn led to veteran cartoonist Avi Katz referencing George Orwell in his sly skewering of the image in the pages of Jerusalem Report, an Israeli English-language fortnightly owned by the Jerusalem Post…

…which in turn got the cartoonist, Katz, who had been contributing material to the Jerusalem Post for three decades, summarily fired. Supposedly for having perpetrated such a baldly anti-Semitic image, pork of course being trayf, which is to say decidedly not kosher, as things were piously explained…

…which of course missed (or more likely intentionally misconstrued) the entire purport of Katz’s Orwellian reference, for in the anti-Stalinist allegory of Animal Farm, the pigs who had led the farm-animals in the uprising against their cruel human masters thereafter slowly transmogrified themselves, assuming human traits and donning human clothes and indulging in all manner of human satisfactions, until by the book’s famous ending, “No question, now, what had happened to the faces of the pigs. The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.” If Orwell had been suggesting that Stalinist communists had transformed themselves into an evil indistinguishable from the capitalist oppressors they’d once opposed, Katz seemed to be suggesting that Zionism itself had now taken on the full trappings of the European fascisms against which it had once risen up in desperate and righteous revulsion.

*

The whole incident in turn put me in mind of another controversy which occurred, back in the year 2000, when Art Spiegelman at long last managed to

get his two-volume Maus chronicle translated and released in a Polish language edition by a diminutive Krakow publishing firm (none of the more established outlets would touch the thing), an edition which, sure enough, in turn was soon being roundly denounced, often in astonishingly strident terms, for the scandal of having rendered Poles as pigs.

At the time, Adam Michnik’s Gazeta Wyborcza, Warsaw’s foremost daily, asked me to interview Spiegelman himself on his intentions in that regard, and an English-language version of the resulting article was subsequently published in the July/August 2001 issue of the late lamented Lingua Franca. As you can imagine, the current fracas in Israel had me returning to that conversation, parts of which I append:

“There were a few countries whose translations really mattered to me,” Spiegelman explained in his SoHo studio, taking a drag on his ever-present cigarette. “France, for example, in part because my wife is French and in part because of the long and highly sophisticated tradition of literary comic books over there. And Germany, of course, where the book proved a considerable best-seller and even gets assigned in classes.

“But a Polish publication of the book has all along been particularly important to me because—how should I say this?—well, the kind of ambivalence the Poles feel toward certain aspects of their past is mutual with me and goes back to my earliest memories. As I was being raised in Rego Park {Queens}, my parents regularly expressed negative feelings about the Poles; but those feelings were regularly being expressed in Polish, so that Polish is really my mother tongue and the comforting lullaby music of my infant life.”

But, I asked, what about the issue of having portrayed Poles as pigs? Countless Polish publishers have told me that if the Poles in Maus hadn’t been portrayed as pigs, there’d never have been the slightest problem about publishing the book.

“To begin with,” Spiegelman said, stiffening slightly, “let’s be honest about this: On this particular subject, if there weren’t any problem, that would be a problem. Look,” he continued, taking another long drag on his cigarette. “For the hundredth time…” He paused, redeploying his thoughts.

Whereupon he launched into a long story about how, after the publication of the first volume of Maus, in 1980, he applied to the Polish consulate for a visa to visit the country, in part so as to study actual locations prior to launching into several of the chronicle’s upcoming scenes. An appointment was made, and

“The day came, and I went up to talk with the guy—entirely cordial. He indicated that they would be granting the visa, but he, too, wanted to know, very concerned: Why Poles as pigs?

“My initial reply, I suppose, was a bit facetious: ‘At first,’ I told him, ‘I tried to render Poles as noble stags, but I eventually found it just too hard inking in all those antlers.’ But then I went on, trying to explain how in the American cartoon tradition, pigs simply don’t carry any particular negative connotation: Porky Pig, for instance, is every bit as cuddly and beloved a figure as Mickey Mouse. Although it wasn’t lost on me that as far as my mother and father were concerned, the main thing about pigs is that they weren’t kosher. Beyond that, in terms of the narrative conventions of the text, the main thing to be noted about pigs is that they are not part of the book’s overriding metaphorical food chain. Pigs don’t eat mice—cats do. Pigs are relatively innocuous as far as mice are concerned.

“The consulate guy nodded politely, but clearly he wasn’t buying my explanations. ‘Mr. Spiegelman,’ he said gravely, at length, ‘the thing you don’t seem to understand is that in Poland calling someone a swine is a much, much greater insult than seems to be the case here in America. Swine, you see, is what the Nazis called the Poles.’

“‘Exactly!’ I replied. ‘And they called us vermin. That’s the whole point.’ You see, I didn’t make up these metaphors, the Nazis did. I was just trying to explore them, to take them seriously, to unravel and deconstruct them. I must say, I keep waiting for some Pole to take umbrage at the fact that I portray Jews as rodents—I mean, I’m not holding my breath or anything, though it would be nice.

“But actually, it’s interesting when you look at those metaphors in the context of the sort of suffering competition that so seems to define Jewish-Polish relations nowadays. Because if you think about the Thousand-Year Reich as a sort of animal farm, to borrow a metaphor, Jews as rodents or vermin were pests to be destroyed and exterminated first thing, indiscriminately, as a matter of course. Whereas Poles as pigs, like all the Slavic races in the entire Nazi conception, while not to be coddled, weren’t to be indiscriminately destroyed: They were to be put to use and worked for their meat. Neither status was enviable, but it’s a distinction worth noting nevertheless.

“Beyond that, though,” Spiegelman went on, “the main thing to ask is that people try to see past those initial metaphors. In terms of the narrative itself, in terms of what actually happened to my mother and father, it’s all very complicated: There were pigs who behaved well and pigs who behaved shabbily, just as there were mice who did likewise… And that’s what things were really like.”

Pausing, he took another deep drag on his cigarette. “That literal-minded way of thinking can get ridiculous. If Maus is about anything,” he concluded, “it’s a critique of the limitations—the sometimes fatal limitations—of the caricaturizing impulse. I did my damnedest not to caricature anybody in this book—and anyone who caricatures my efforts in any other light, I’m sorry, that’s their problem, not mine.”

*

And indeed, it’s an open question as to who should be getting fired up—and who fired—in the context of the publication of Katz’s cartoon, and the issues it so trenchantly surfaces.

What the Spiegelman interview surfaced for me personally, however, was something altogether different: fond memories of Piotr Bikont, the Rabelaisian Polish polymath documentary filmmaker/food writer/theater director/jazz vocalist/and beat translator (Ferlinghetti! Ginsburg!)

who undertook the daunting task of translating Maus in the first place, seeing to its publication and then weathering the controversy. (Can you imagine the roiling complications involved in translating the distinctive Polish and Yiddish inflected English of Spiegelman’s parents back into Polish? And yet I’m told that Bikont’s stylings were singularly effective.)

In his book Metamaus, Spiegelman includes a completely fetching image of Bikont at the balcony of Gazeta Wyborcza, confronting a gaggle of furious nationalist demonstrators down below, merrily enswathed in a pig mask!

Aye, Bikont! Huge and hulking, he was one of my favorite informants during my years covering the Polish transition out of communism for the New Yorker. As a filmmaker he’d himself been one of the most vital documentarians of that transition, including a legendary scene in his August 1988 strike film in which the camera he had slung over his shoulder, as he was interviewing some of the resolute strikers, was suddenly yanked right off his back—having, just before that, registered the suddenly shocked faces of his interviewees. {You can view the entire Ballad of a Strike film here, though it’s only in Polish with no subtitles—still the actual incident in question, starting around minute 45:29 hardly needs translation.} Hijacked by an undercover police goon, the camera continues recording its own kidnapping all the while, the frantic upside-down foot-chase with strikers in hot pursuit, leading to the seeming safety of the police barracks where the camera (still recording) gets placed on the floor {with the goon presently getting a phone call from central command, who among other things, at 48:24, ask what kind of camera it is} as in the background you can make out the ruckus outside as a besieging crowd of workers lustily demands their camera back, a demand to which the abashed policeman presently accedes. (A few years later, as a restaurant critic in the early days of the ensuing transition, Bikont liked to say he was engaging in a sort of delectable science fiction, so beyond the means of his average reader were the repasts he was initially reviewing—and yet how those pieces were themselves savored!)

Aye Bikont, I say, because just last year {2017} he was tragically and ridiculously killed: felled, his spine severed, when the car in which he was sitting was rear-ended by a recklessly speeding vehicle. I still can’t believe he’s gone.

* * *

And speaking of Bikont…

INDEX SPLENDORUM

As it happens, followers of The Believer/McSweeney’s universe might have remembered Bikont as the booming declamatory voice in his Polish jazz band Free Cooperation’s rendition of passages from the great minimalist artist Ad Reinhardt’s “Art in Art is Art-as-Art” scroll-poem soliloquy, in a piece called “Convergence,” which had been included on the bespoke CD folded into McSweeney’s #6. Shortly after Bikont’s passing, somebody posted a video of a live performance of the same piece from a few months earlier, with Bikont still belting away!

Nobody quite like Bikont, bless his anarchic soul, channeling Reinhardt (bless his, too!) to set us all straight on what’s what and what’s not when it comes to art and truth.

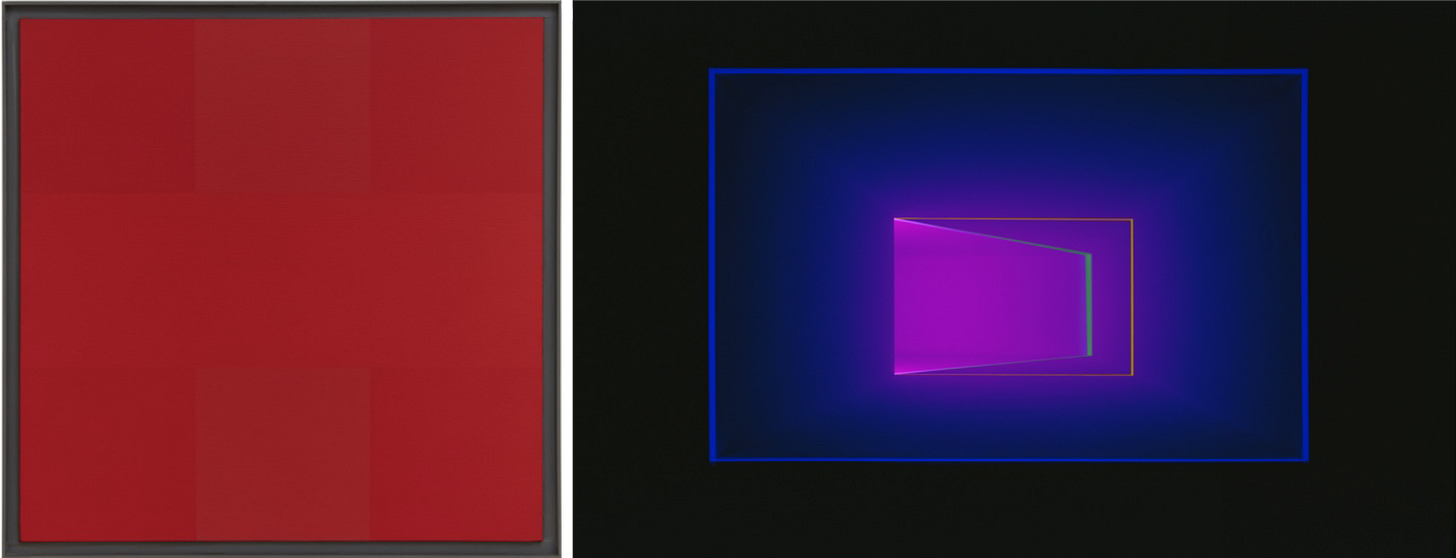

(Incidentally, fans of Reinhardt will be happy to hear that James Turrell has curated a show of his predecessor’s work, alongside a piece of his own, up now at the Pace Gallery in New York through March 19, 2022.)

* * *

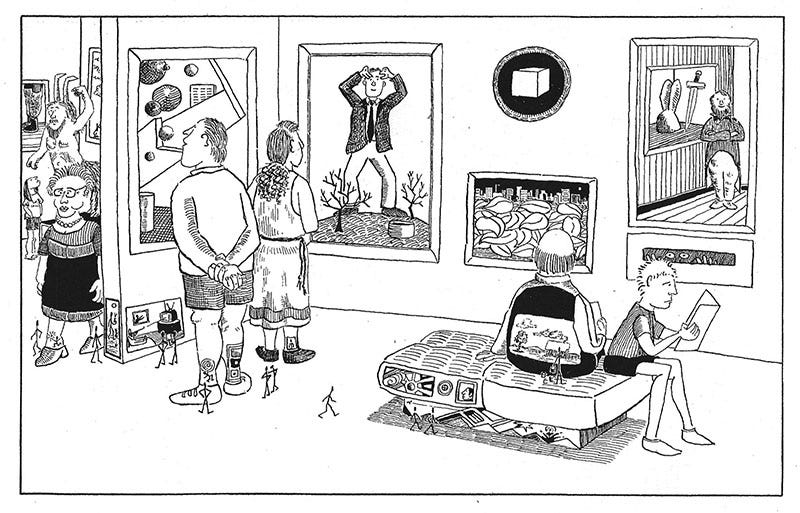

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

We’ll be launching an extended multi-issue serialization based on the introduction to Ren’s long-gestating, soonish-to-be-published sequel to his 2006 compendium Everything that Rises: A Book of Convergences, to wit: “All that is Solid: Toward a Taxonomy of Convergences & A Unified Field Theory of Cultural Transmission.” Just wait, you’ll see: lots of fun, loads of unexpected vantages, and a perfect occasion to invite others of your friends into our ever-expanding Wondercabinet community, simply by tapping the Share link below. (It’s free to them and really important to us.)